Marine iguana

| Marine iguana | |

|---|---|

%2C_Las_Bachas%2C_isla_Santa_Cruz%2C_islas_Gal%C3%A1pagos%2C_Ecuador%2C_2015-07-23%2C_DD_23.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Iguania |

| Family: | Iguanidae |

| Genus: | Amblyrhynchus Bell, 1825 |

| Species: | A. cristatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Amblyrhynchus cristatus (Bell, 1825) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

7 ssp.; see text | |

| |

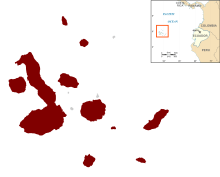

The marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) is an iguana found only on the Galápagos Islands that has the ability, unique among modern lizards, to forage in the sea, making it a marine reptile. The iguana can dive over 9 m (30 ft) into the water. It has spread to all the islands in the archipelago, and is sometimes called the Galápagos marine iguana. It mainly lives on the rocky Galápagos shore to warm from the comparatively cold water, but can also be spotted in marshes and mangrove beaches.

%2C_Las_Bachas%2C_isla_Santa_Cruz%2C_islas_Gal%C3%A1pagos%2C_Ecuador%2C_2015-07-23%2C_DD_27.jpg)

Subspecies

Listed alphabetically.[2]

- A. c. albemarlensis Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1962 – Isabela Island

- A. c. cristatus Bell, 1825 – Fernandina Island

- A. c. hassi Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1962 – Santa Cruz Island

- A. c. mertensi Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1962 – San Cristóbal and Santiago Islands

- A. c. nanus Garman, 1892 – Genovesa Island

- A. c. sielmanni Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1962 – Pinta Island

- A. c. venustissimus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1956 – Española Island (and adjacent tiny Gardener Island)

-

A. c. albemarlensis

-

%2C_male%2C_Fernandina_Island.jpg)

A. c. cristatus

-

%2C_male%2C_Santa_Cruz_Island.jpg)

A. c. hassi

-

%2C_Santiago_Island%2C_Ecuador.jpg)

A. c. mertensi

-

%2C_male%2C_Genovesa_Island.jpg)

A. c. nanus

-

A. c. venustissimus

Characteristics

%2C_Las_Bachas%2C_isla_Santa_Cruz%2C_islas_Gal%C3%A1pagos%2C_Ecuador%2C_2015-07-23%2C_DD_19.jpg)

On his visit to the islands, despite making extensive observations on the creatures, Charles Darwin was revolted by the animals' appearance, writing:

- The black Lava rocks on the beach are frequented by large (2–3 ft [0.6–0.9 m]), disgusting clumsy Lizards. They are as black as the porous rocks over which they crawl & seek their prey from the Sea. I call them 'imps of darkness'. They assuredly well-become the land they inhabit.[3]

Marine iguanas are medium-sized lizards (200–340 mm (7.9–13.4 in), adult snout–vent length) and are unique as they are marine reptiles due to their foraging on inter- and subtidal algae only. These iguanas forage exclusively in the cold sea, which leads them to behavioral adaptations for thermoregulation.[4]

Amblyrhynchus cristatus is not always black; the young have a lighter coloured dorsal stripe, and some adult specimens are grey, and adult males vary in colour with the season. Dark tones allow the lizards to rapidly absorb heat to minimize the period of lethargy after emerging from the water. The marine iguana lacks agility on land but is a graceful swimmer. Its laterally flattened tail and spiky dorsal fin aid in propulsion, while its long, sharp claws allow it to hold onto rocks in strong currents.[5]

Body size and longevity

Marine iguanas vary in body size, which is different depending on the island the individual iguana inhabits. The iguanas living on the islands of Fernandina and Isabela (named for the famous rulers of Spain) are the largest found anywhere in the Galápagos. On the other end of the spectrum, the smallest iguanas are found on the island on Genovesa.

Adult males weigh from a maximum of 12–13 kg (26–29 lb) on southern Isabela to about 1–2 kg (2.2–4.4 lb) on Genovesa. The reason for this difference in body size of marine iguanas between islands is due to "variability in algal productivity and sea surface temperature." [6]

Marine iguanas are sexually dimorphic with adult males weighing about 70% more than adult females.[7] There is a correlation between longevity and body size, particularly for adult males. Large body size in males is selected sexually, but can be detrimental during El Niño events when resources are scarce. This results in large males suffering higher mortality than females and smaller adult males. The mortality rates of marine iguanas are, in fact, explained through the size difference between the sexes.[7]

Reproduction

Reproduction in the marine iguana begins during the cold and dry season. Female marine iguanas reach sexual maturity at the age of 3–5 years, while males reach sexual maturity at the age of 6–8 years. Sexual maturity is marked by the first steep and abrupt decline in bone growth cycle thickness.[4]

Males are selected by females on the basis of their body size. Females display a stronger preference for mating with bigger males.[8] During the breeding season, males defend the leks, and roughly one month after copulation, females lay between one and six eggs. The eggs "take three months to incubate in nests dug 30–80 cm (12–31 in) deep in sand or volcanic ash." [7] It is precisely because of body size that reproductive performance increases and "is mediated by higher survival of larger hatchlings from larger females and increased mating success of larger males."[9]

Diet

The marine iguana forages exclusively on inter- and subtidal algae, and 4–5 red algal species are their food of choice. During neap low tides, however, the usually avoided Ulva lobata, also known as green algae, is eaten more often since the preferred red algae are not easily available.[10]

This algal diet varies in accordance to the algal abundance, preferences, and foraging behaviour. Only 5% of marine iguanas dive for algae offshore, and these individuals are the large males. This behaviour is advantageous because these males experience less competition for food from smaller males and females, who are restricted to foraging during low tide.[11] Foraging behavior changes in accordance to the seasons and foraging efficiency increases with temperature.[10] These environmental changes and the ensuing occasional food unavailability have caused marine iguanas to evolve by acquiring efficient methods of foraging in order to maximize their energy intake and body size.[6] In fact, during an El Niño cycle in which food diminished for two years, some were found to decrease their length by as much as 20%. When food supply returned to normal, iguana size followed suit. It is speculated that the bones of the iguana actually shorten as shrinkage of connective tissue could only account for a 10% change in length.[12]

The physical structure of the iguana also facilitates foraging as they have “long claws, tough skin, blunt heads, flattened tails, and well-developed salt glands.” A flat snout and sharp teeth enable it to browse on algae growing on rocks.[10] A nasal gland filters its blood for excess salt ingested while eating, which is expelled through the nostrils, often leaving white patches of salt on its face.

Behavior

As an ectothermic animal, the marine iguana can spend only a limited time in cold water diving for algae. Afterwards it basks in the sun to warm up. Until it can do so it is unable to move effectively, making it vulnerable to predation. However, this is counteracted by their highly aggressive nature consisting of biting and expansive bluffs when in this disadvantageous state. Their dark shade aids in heat reabsorption.[13]

Fights sometime occur during the breeding season but are generally harmless; males will bob their heads as a threat and if the other suitor responds, both will thrust their heads together until one backs away.[14]

Evolutionary history

Researchers theorize that land iguanas and marine iguanas evolved from a common ancestor since arriving on the islands from South America, presumably by rafting.[15][16] The marine iguana diverged from the land iguana some 8 million years ago, which is older than any of the extant Galapagos islands.[17] It is therefore thought that the ancestral species inhabited parts of the volcanic archipelago that are now submerged. The two species remain mutually fertile in spite of being assigned to distinct genera, and they occasionally hybridize where their ranges overlap.

The subspecies of the marine iguana are identifiable by their sizes as well as by distinct colorations. For example, the Espanola race is redder while the Santiago iguanas are greener.[14] The marine iguanas may appear to have a light colored face, but in fact, this is due to salt from specialised cranial exocrine glands, expelled from the body in a process much like sneezing. This salt becomes encrusted on their faces. This adaptation allows them to excrete excess salt due to foraging on marine algae.[14] Although the marine iguana resembles a lizard, it has developed several adaptations that set it apart. These include blunt noses for efficiently grazing seaweed, powerful limbs and claws for climbing and holding onto rocks, and laterally flattened tails for improved swimming.[18] Compared to the land iguana its limb bones, especially those from the front limbs, have become more heavy and compact (osteosclerosis), providing ballast to help with diving.[19]

The marine iguana has no evolved defences against introduced predators. These include rats, which tend to feed on the eggs, cats, which can feed on juveniles, and dogs which may threaten adults.[14]

Taxonomy and etymology

Its generic name, Amblyrhynchus, is a combination of two Greek words, Ambly- from Amblus (ἀμβλυ) meaning "blunt" and rhynchus (ρυγχος) meaning "snout". Its specific name is the Latin word cristatus meaning "crested," and refers to the low crest of spines along the animal's back.

Amblyrhynchus is a monotypic genus, having only one species, Amblyrhynchus cristatus.

Endangered Species List

The marine iguana is currently labeled as vulnerable in its conservation status. The iguana is only known to be living in the Galapagos Islands and its population has been gradually decreasing throughout the years. Since the environment in which they live didn't have many natural predators they never developed the defenses needed to help protect them against new enemies. This lack of development makes them more vulnerable to attack and becoming ill due to new bacteria as these islands attract more and more people and animals from different parts of the world.

Although unintentional, human beings pose one of the most serious threats to this species. The marine iguana has evolved over time in an isolated environment and lacks immunity to many pathogens. As a result, the iguanas are at higher risk of contracting infections, contributing to their endangerment.[20]

Other predators include animals such as pigs, dogs, and cats. These animals, though they usually pose little threat to adult iguanas, do impact their reproduction by feeding off their eggs. This inhibits reproduction and the long-term survival of the species.[21]

Conservation

The marine iguana is completely protected under the laws of Ecuador, and is listed under CITES Appendix II. The total population size is unknown, but the International Union of Conservation of Nature estimates that at least 50,000 exist, while estimates from the Charles Darwin Research Station are in the hundreds of thousands.

Studies and research have been done on Galapagos marine iguanas that can help and promote conservation efforts to preserve the endemic species. Monitoring levels of marine algae, both dimensionally and hormonally, is an effective way to predict the fitness of the marine iguana species. Exposure to tourism affects marine iguanas, and corticosterone levels can predict their survival during El Niño events.[22] Corticosterone levels in species measure the stress that they face in their populations. Marine iguanas show higher stress-induced corticosterone concentrations during famine (El Niño) than feast conditions (La Niña). The levels differ between the islands, and show that survival varies throughout them during an El Niño event. The variable response of corticosterone is one indicator of the general public health of the populations of marine iguanas across the Galapagos Islands, which is a useful factor in the conservation of the species.[23]

Another indicator of fitness is the levels of glucocorticoid. Glucocorticoid release is considered beneficial in helping animals survive stressful conditions, while low glucocorticoid levels are an indicator of poor body condition. Species undergoing a large measure of stress, resulting in elevated glucocorticoid levels can cause complications such as reproduction failure. Human activity has been considered a cause of elevated levels of glucocorticoid in species. Results of a study show that marine iguanas in areas central to tourism are not chronically stressed, but do show lower stress response compared to groups undisturbed by tourism. Tourism, thus, does affect the physiology of marine iguanas. Information of glucocorticoid levels are good monitors in predicting long term consequences of human impact.[24]

See also

Bibliography

- Rothman, Robert, Marine Iguana Galapagos Pages. Rochester Institute of Technology. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

References

- ↑ Nelson, K.; Snell, H. & Wikelski, M. (2004). "Amblyrhynchus cristatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 2012-09-26.

- ↑ Amblyrhynchus cristatus, Reptile Database

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (2001). Charles Darwin's Beagle Diary. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 494. ISBN 0-521-00317-2.

- 1 2 Jasmina, Hugi; Marcelo R., Sánchez-Villagra (2012). "Life History and Skeletal Adaptations in the Galapagos Marine Iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) as Reconstructed with Bone Histological Data—A Comparative Study of Iguanines". Journal of Herpetology. 46 (3): 312–324. doi:10.1670/11-071.

- ↑ Vitousek, M.N., Rubenstein, D.R., Wikelski, M. (2007). The evolution of foraging behavior in the Galápagos marine iguana: natural and sexual selection on body size drives ecological, morphological, and behavioral specialization. In Lizard Ecology: The Evolutionary Consequences of Foraging Mode, S.M. Reilly, McBrayer, L.D., Miles, D.B., ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press), pp. 491-507.

- 1 2 Reilly, Stephen M.; McBrayer, Lance D.; Miles, Donald B., eds. (2007). "16: The Evolution of Foraging Behavior in the Galápagos Marine Iguana: Natural and Sexual Selection on Body Size Drives Ecological, Morphological, and Behavioral Specialization". Lizard Ecology. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 491–507.

- 1 2 3 W. A., Laurie; D., Brown (June 1990). "Population Biology of Marine Iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus). II. Changes in Annual Survival Rates and the Effects of Size, Sex, Age and Fecundity in a Population Crash". Journal of Animal Ecology. 59 (2): 529–544. doi:10.2307/4879.

- ↑ Wikelski, Martin; Trillmich, Fritz (June 1997). "Body Size and Sexual Size Dimorphism in Marine Iguanas Fluctuate as a Result of Opposing Natural and Sexual Selection: An Island Comparison". Evolution. 51 (3): 922–936. doi:10.2307/2411166.

- ↑ Wikelski, Martin; Romero, L. Michael (2003). "Body Size, Performance and Fitness in Galapagos Marine Iguanas". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43: 376–386. doi:10.1093/icb/43.3.376.

- 1 2 3 Scoresby A., Shepherd; Michael W., Hawkes (2005). "Algal Food Preferences and Seasonal Foraging Strategy of the Marine Iguana, Amblyrhynchus Cristatus, on Santa Cruz, Galápagos". Bulletin of Marine Science. 77 (1): 51–72.

- ↑

- ↑ M, Wikelski; Thom, C. (Jan 6, 2000). "Marine iguanas shrink to survive El Niño". Nature. 403 (6765): 37–8. doi:10.1038/47396. PMID 10638740.

- ↑ Kristi, Roy. "Amblyrhynchus cristatus: Marine Iguana". Animal Diversity Web.

- 1 2 3 4 "Marine Iguanas". Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ Rassman K, Tautz D, Trillmich F, Gliddon C (1997), The micro - evolution of the Galápagos marine iguana Amblyrhynchus cristatus assessed by nuclear and mitochondrial genetic analysis.: Molecular Ecology 6:437–452

- ↑ Marine Iguana: marinebio.org. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ "Explaining the Divergence of the Marine Iguana Subspecies on Espa". Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ "Galapagos Marine Iguana". Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Hugi, J.; Sanchez-Villagra, M. R. (2012). "Life History. and Skeletal Adaptations in the Galapagos Marine Iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) as Reconstructed with Bone Histological Data-A Comparative Study of Iguanines". Journal of Herpetology. 46 (3): 312–324. doi:10.1670/11-071.

- ↑ French, Susannah; DeNardo, Dale; Greives, Timothy; Strand, Christine; Demas, Gregory (Nov 2010). "Human disturbance alters endocrine and immune responses in the Galapagos marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus)". Hormones and Behavior. 58 (5): 792–799. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.08.001. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ↑ Berger, Silke; Wikelski, Martin; Romero, Michael; Kalko, Elisabeth; Roedl, Thomas (Dec 2007). "Behavioral and physiological adjustments to new predators in an endemic island species, the Galapagos marine iguana". Hormones and Behavior. 52 (5): 653–663. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.08.004. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ Stevenson, R. D.; Jr Woods, William A. (2006). "Condition Indices For Conservation: New Uses For Evolving Tools". Integrative & Comparative Biology. 46 (6): 1169–1190. doi:10.1093/icb/icl052.

- ↑ Romero, Michael L. Wikelski Martin (2001). "Corticosterone Levels Predict Survival Probabilities of Galapagos Marine Iguanas during El Nino events". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (13): 7366–70. doi:10.1073/pnas.131091498.

- ↑ Romero, Michael L. Wikelski; Martin (2002). "Exposure to Tourism Reduces Stress-induced Corticosterone Levels in Galapagos Marine Iguanas". Biological Conservation. 108 (3): 371–374. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(02)00128-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Amblyrhynchus cristatus |

- Marine Iguana Podcast - Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- Images of Marine and Land Iguanas

- Iguanas of the Galapagos www.galapagosonline.com

- ARKive videos and slide show