American Civil War prison camps

American Civil War Prison Camps were operated by both the Union and the Confederacy to handle the 409,000 soldiers captured during the war, 1861–1865. The Record and Pension Office in 1901 counted 211,000 Northerners who were captured. In 1861-63 most were immediately paroled; after the parole exchange system broke down in 1863, about 195,000 went to prison camps. Some tried to escape but few succeeded. By contrast 464,000 Confederates were captured (many in the final days) and 215,000 imprisoned. Over 30,000 Union and nearly 26,000 Confederate prisoners died in captivity. Just over 12% of the captives in Northern prisons died, compared to 15.5% for Southern prisons.[1]

Parole

Lacking means for dealing with large numbers of captured troops early in the American Civil War, the Union and Confederate governments both relied on the traditional European system of parole and exchange of prisoners. A prisoner who was on parole promised not to fight again until his name was "exchanged" for a similar man on the other side. Then both of them could rejoin their units. While awaiting exchange, prisoners were briefly confined to permanent camps. The exchange system broke down in 1863 when the Confederacy refused to treat captured black prisoners as equal to white men. The prison populations soared. There were 32 major Confederate prisons; 16 were in the Deep South states of Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina.[2] Training camps were turned into prisons, and new settlements were made. The Union always had plenty of men but the Confederacy did not and the loss of its men to Northern prisons hurt the Southern economy and war effort.

Prisoner exchanges

At the outbreak of the War, the Federal government avoided any action, such as prisoner exchanges, that might appear as an official recognition of the Confederate government in Richmond, including the formal transfer of military captives. In the North, public opinion on prisoner exchanges changed after the First Battle of Bull Run, when the rebels captured about one thousand Union soldiers.[3]

Union and Confederate forces exchanged prisoners sporadically, usually as an act of humanity between opposing field commanders. Throughout the initial months of the Civil War, support for prisoner exchanges grew in the North. Petitions from prisoners in Southern captivity and articles in Northern newspapers increased pressure on the Lincoln administration.[4] On December 11, 1861, the US Congress passed a joint resolution calling on President Lincoln to "inaugurate systematic measures for the exchange of prisoners in the present rebellion."[5] In two meetings on February 23 and March 1, 1862, Union Major Gen. John E. Wool and Confederate Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb met to reach an agreement on prisoner exchanges. They discussed many of the provisions later adopted in the Dix-Hill agreement. However, differences over which side would cover expenses for prisoner transportation stymied the negotiations.

Dix-Hill Cartel of 1862

Prisoner camps were largely empty in mid-1862 because of the informal exchange system. Both sides agreed to formalize it. Negotiations resumed in July, 1862, when the Union appointed Maj. Gen. John A. Dix and the Confederacy appointed Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill. The cartel agreement established a scale of equivalents to manage the exchange of military officers and enlisted personnel. For example, a naval captain or a colonel in the army would exchange for fifteen privates or common seamen, while personnel of equal ranks would transfer man for man. Each government would appoint an agent to handle the exchange and parole of prisoners. The agreement allowed the exchange of non-combatants, such as citizens accused of disloyalty, and civilian employees of the military, and also allowed the exchange or parole of captives between the commanders of two opposing forces.

Authorities were to parole any prisoners not formally exchanged within ten days following their capture. The terms of the cartel prohibited paroled prisoners from returning to the military in any capacity including "the performance of field, garrison, police, or guard, or constabulary duty."[6]

End of exchanges

The exchange system collapsed in 1863 because the Confederacy refused to treat black prisoners the same as whites. They said they were probably ex-slaves and belonged to their masters, not to the Union Army.[7] The South needed the exchanges much more than the North did, because of the severe manpower shortage in the Confederacy. In 1864 Ulysses Grant, noting the "prisoner gap" (Union camps held far more prisoners than Confederate camps), decided that the growing prisoner gap gave him a decided military advantage. He therefore opposed wholesale exchanges until the end was in sight. Around 5600 Confederates were allowed to join the Union Army. Known as "Galvanized Yankees" these troops were stationed in the West facing Indians. Around 1600 former Union troops joined the Confederate army.[8]

In 1865, as the war was ending, the Confederates sent 17,000 prisoners North while receiving 24,000 men.[9] On April 23, after the war ended, the riverboat Sultana was taking 1900 ex-prisoners North on the Mississippi River when it exploded, killing about 1500 of them.

Death rates

The overall mortality rates in prisons on both sides were similar, and quite high. Many Southern prisons were located in regions with high disease rates, and were routinely short of medicine, doctors, food and ice. Northerners often believed their men were being deliberately weakened and killed in Confederate prisons, and demanded that conditions in Northern prisons be equally harsh, even though shortages were not a problem in the North.[10]

About 56,000 soldiers died in prisons during the war, accounting for almost 10% of all Civil War fatalities.[11] During a period of 14 months in Camp Sumter, located near Andersonville, Georgia, 13,000 (28%) of the 45,000 Union soldiers confined there died.[12] At Camp Douglas in Chicago, Illinois, 10% of its Confederate prisoners died during one cold winter month; and Elmira Prison in New York state, with a death rate of 25%, very nearly equaled that of Andersonville.[13]

Main camps

| Side | Name & site | Notes on the camp | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Union | Camp Chase, Columbus, Ohio | Operated May 1861 to 1865. The capacity of 4,000 was at times stretched to more than 7,000. It was expanded to a capacity of 7,000 but late in the war it held up to 10,000 men.[14] |  The memorial to the Confederate dead at Camp Chase |

| Union | Camp Douglas, Chicago, Illinois | Established in January 1863 as a permanent POW camp. It became notorious for its poor conditions and death rate of between 17% and 23% percent. | |

| Union | Camp Morton, Indianapolis, Indiana | In operation between 1862 and 1865, the camp's average prison population was 3,214. | Camp Morton |

| Union | Elmira Prison, Elmira, New York | Became a prisoner of war camp in 1864 with a capacity of 12,000. Some 2,963 prisoners died from various causes.[15] | |

| Union | Fort Delaware, Delaware City, Delaware | ||

| Union | Fort Pulaski, Savannah, Georgia | Confederate soldiers were intentionally starved, see Immortal Six Hundred | Room used for Confederate POWs |

| Union | Fort Slocum, New York City | Used from July 1863 to October 1863 as a temporary hospital for Confederate soldiers. | The main buildings behind the parade ground of Fort Slocum, taken around 1930 |

| Union | Fort Warren, Boston, Massachusetts | [16] |  Aerial photo of Georges Island and Fort Warren |

| Union | Gratiot Street Prison, St. Louis, Missouri | [17] | |

| Union | Johnson's Island, Sandusky, Ohio | for officers [18] | The cemetery at Johnson's Island |

| Union | Ohio Penitentiary, Columbus, Ohio | [19] | |

| Union | Old Capitol Prison, Washington, D.C. | [20] |  The Old Brick Capitol serving as a prison during the Civil War. |

| Union | Point Lookout, Saint Mary's County, Maryland | [21] | Point Lookout Confederate Cemetery Monument |

| Union | Rock Island Prison, Rock Island, Illinois | An island in the Mississippi River[22] | |

| CSA | Andersonville, Andersonville, Georgia | The site is the National POW Museum |  Andersonville POW camp. |

| CSA | Belle Isle, Richmond, Virginia | ||

| CSA | Blackshear Prison, Blackshear, Georgia | [23] | |

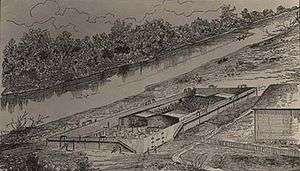

| CSA | Cahaba Prison (Castle Morgan), Selma, Alabama |  "Castle Morgan, Cahaba, Alabama, 1863–65. Drawn from memory by the author." From Jesse Hawes' Cahaba, A Story of Captive Boys in Blue. | |

| CSA | Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas | First prisoners August 1863; Four acre stockade built Nov. 1863; expanded to 11 acres, April, 1864; maximum population c. 5,000 July 1864. Final 1,815 prisoners exchanged May 27, 1865, Red River Landing on the Mississippi. Total of 329 dead out of 5,493 identified prisoners resulted in a death rate of 5.9 %, making it one of the least deadly camps in the war. The site is now an interpretive Historic Park.[24][25] |  Camp Ford Lithograph |

| CSA | Castle Pinckney, Charleston, South Carolina |  Federal prisoners captured at the First Battle of Bull Run were transported to Charleston S.C. and held inside a makeshift prison at Castle Pinckney. | |

| CSA | Castle Thunder, Richmond, Virginia |  Castle Thunder prison. Richmond, Virginia. 1865. | |

| CSA | Danville Prison, Danville, Virginia | ||

| CSA | Florence Stockade, Florence, South Carolina | ||

| CSA | Libby Prison, Richmond, Virginia | for officers[26] |  A photo of Libby Prison (1865) |

| CSA | Salisbury Prison, Salisbury, North Carolina |  Salisbury Prison, 1861 |

See also

- Prisoner-of-war camp, worldwide history

- Henry Wirz, commander at Andersonville; executed for war crimes

Notes

- ↑ James Ford Rhodes (1904). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850: 1864-1866. Harper & Brothers. pp. 507–8.

- ↑ Roger Pickenpaugh, Captives in Gray: The Civil War Prisons of the Union (2009)

- ↑ Hesseltine, Civil War Prisons, pp. 9-12.

- ↑ Hesseltine, Civil War Prisons, pp. 9-12.

- ↑ Official Records, Series II, Vol. 3, p. 157.

- ↑ WikiSource. "WikiSource: Dix-Hill Cartel". Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Mark Grimsley; Brooks D. Simpson (2002). The Collapse of the Confederacy. U of Nebraska Press. p. 88.

- ↑ National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior (1992). "The Galvanized Yankees" (PDF). Experience Your America (July). Retrieved 2 Jan 2012.

- ↑ Pickenpaugh, Captives in Blue p 232

- ↑ The position is denied in James Gillispie, Andersonvilles of the North: The Myths and Realities of Northern Treatment of Civil War Confederate Prisoners (2012); he says there was no conspiracy to maltreat Confederate prisoners. However, he compares the death rates in Northern camps with the death rates of Confederate soldiers in a Confederate hospital that faced severe shortages; he did not compare with a Union hospital for Union soldiers.

- ↑ Chambers and Anderson (1999). The Oxford Companion to American Military History. p. 559.

- ↑ "Andersonville: Prisoner of War Camp-Reading 1". Nps.gov. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ↑ Yancey Hall ""US Civil War Prison Camps Claimed Thousands". National Geographic News. July 1, 2003.

- ↑ "Camp Chase Civil War Prison". Censusdiggins.com. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ Horigan, Michael (2002). Death Camp of the North: The Elmira Civil War Prison Camp. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-1432-2.

- ↑ "Preservationists Seek Funds For Film About Boston's Fort Warren". Civilwarnews.com. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ↑ "Gratiot Street Prison". Civilwarstlouis.com. 2001.

- ↑ see National Park Service website

- ↑ "Ohio State Penitentiary". Wtv-zone.com. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ↑ Colonel N. T. Colby (2002). "The "Old Capitol" Prison". Civilwarhome.com. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ↑ "Point Lookout State Park History". Maryland Department of Natural Resources. 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-12-19. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ "Rock Island National Cemetery, Arsenal, and Confederate POW Camp". Illinoiscivilwar.org. 2007. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ↑ "Blackshear Prison Camp". Piercecounty.www.50megs.com. 2000-06-15. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ↑ Smith County Historical Society, Inc., A New Look at Camp Ford (2009):also OR Ser.II, Vol.8, p 576

- ↑ "Camp Ford". The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 2012-11-03.

- ↑ Frank L. Byrne, "Libby Prison: A Study in Emotions," Journal of Southern History (1958) 24#4 pp. 430-444 in JSTOR

Bibliography

General

- Burnham, Philip. So Far from Dixie: Confederates in Yankee Prisons (2003)

- Butts, Michele Tucker. Galvanized Yankees on the Upper Missouri: The Face of Loyalty (2003); Confederate POWs who joined the US Army

- Current, Richard N. et al., eds. Encyclopedia of the Confederacy (1993); reprinted in The Confederacy: Macmillan Information Now Encyclopedia (1998), articles on "Prisoners of War" and "Prisons"

- Gillispie, James M. Andersonvilles of the North: The Myths and Realities of Northern Treatment of Civil War Confederate Prisoners (2012) excerpt and text search

- Hesseltine, William B. Civil War Prisons: A Study in War Psychology. (Ohio State University Press, 1930)

- Hesseltine, William B. "The Propaganda Literature of Confederate Prisons," Journal of Southern History (1935) 1#1 pp. 56–66 in JSTOR

- Pickenpaugh, Roger. Captives in Blue: The Civil War Prisons of the Confederacy (2013) excerpt and text search

- Pickenpaugh, Roger. Captives in Gray: The Civil War Prisons of the Union (2009)

- Rhodes, James Ford Rhodes (1904). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850: 1864-1866. Harper & Brothers. pp. 483–508 vol 4 ch 29., for an impartial account. another copy online

- Robins, Glenn. "Race, Repatriation, and Galvanized Rebels: Union Prisoners and the Exchange Question in Deep South Prison Camps," Civil War History (2007) 53#2 pp. 117–140 in Project MUSE

- Sanders, Charles W., Jr. While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War. (Louisiana State University Press, 2005)

- Speer, Lonnie R. Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War. (1997).

- Speer, Lonnie. War of Vengeance: Acts of Retaliation Against Civil War POWs. (Stackpole Books, 2002)

Specific camps

- Arnold–Scriber, Theresa and Terry G. Scriber. Ship Island, Mississippi: Rosters and History of the Civil War Prison (McFarland, 2012) excerpt and text search

- Byrne, Frank L., "Libby Prison: A Study in Emotions," Journal of Southern History 1958 24(4): 430-444. in JSTOR

- Casstevens, Frances. George W. Alexander and Castle Thunder: A Confederate Prison and Its Commandant. (McFarland, 2004)

- Davis, Robert Scott. Ghosts and Shadows of Andersonville: Essays on the Secret Social Histories of America's Deadliest Prison (Mercer University Press, 2006) 310pp

- Fetzer, Jr., Dale and Bruce E. Mowdey. Unlikely Allies: Fort Delaware's Prison Community in the Civil War (Stackpole Books, 2002)

- Genoways, Ted & Hugh H. Genoways (eds.), A Perfect Picture of Hell: Eyewitness Accounts by Civil War Prisoners from the 12th Iowa, (U of Iowa Press, 2001).

- Gray, Michael P. The Business of Captivity in the Chemung Valley: Elmira and Its Civil War Prison (2001) online

- Hesseltine William B., ed. Civil War Prisons (1972) 123 pp reprints among others:

- Futch, Ovid. "Prison Life at Andersonville," Civil War History (1962) 8#2 pp. 121–135

- McLain, Minor H. "The Military Prison At Fort Warren," Civil War History (1962) 8#2 pp. 135–151.

- Robertson, James I., Jr. "The Scourge of Elmira," Civil War History (1962) 8#2 pp. 184–201.

- Walker, T. R. "Rock Island Prison Barracks," Civil War History (1962) 8#2 pp. 152–163.

- Hesseltine, William B. "Andersonville Revisited," The Georgia Review (1956) 10#1 pp. 92–101 in JSTOR

- Horigan, Michael. Elmira: Death Camp of the North. (Stackpole Books, 2002)

- Levy, George. To Die in Chicago: Confederate Prisoners at Camp Douglas, 1862–65. (2nd ed. 1999) excerpt and text search.

- Marvel, William. Andersonville: The Last Depot (University of North Carolina Press, 1994)

- McAdams, Benton. Rebels at Rock Island: The Story of a Civil War Prison (2000)

- Richardson, Rufus B. "Andersonville," New Englander and Yale Review (November 1880) 39# 157 pp. 729–774 online

- Triebe, Richard H. Fort Fisher to Elmira: The Fateful Journey of 518 Confederate Soldiers. CreateSpace, 2011.

- Waggoner, Jesse. "The Role of the Physician: Eugene Sanger and a Standard of Care at the Elmira Prison Camp," Journal of the History of Medicine & Allied Sciences (2008) 63#1 pp 1–22; Sanger reportedly boasted of killing enemy soldiers

- Wheelan, Joseph. Libby Prison Breakout: The Daring Escape from the Notorious Civil War Prison. New York: Public Affairs, 2010.

Historiography

- Chesson, Michael B. "Prison Camps and Prisoners of War," in Steven E. Woodworth, ed. The American Civil War (1996), 466-78; good review of published studies. online

- Cloyd, Benjamin G. Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory (Louisiana State University Press; 2010) 272 pages.traces shifts in Americans' views of the brutal treatment of soldiers in both Confederate and Union prisons, from raw memories in the decades after the war to a position that deflected responsibility. excerpt and text search

- Robins, Glenn. "Andersonville in History and Memory," Georgia Historical Quarterly (2011) 95#3, pp 408–422; extended review of Cloyd (2010)

Fiction

- Kantor, MacKinlay. Andersonville (1956) a novel that won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction

Primary Sources

- reports from Harper's Weekly 1863-64; illustrated

- Civil War Research Database search for individual soldiers

- Chandler's 1864 Confederate report; the single most important original document. From Official Records series. ii. vol. vii. pp. 546–551

- Extracts from the Minutes of Proceedings of the Standing Committee of the United States Sanitary Commission...1864 , with hair-raising details

- Appendix to the Report of the Sanitary Commission (1864) much more detail

- Trial of Captain Henry Wirz with documents

- Ransom, John. Andersonville] (original edition 1881; reprinted as Andersonville Diary); first person account that greatly exaggerated conditions; historians consider it untrustworthy as a primary source.

- Robert H. Kellogg, Life and Death in Rebel Prisons (1866) ch 1

- prison letters from Massachusetts men who died in prison

External links

- Andersonville National Historic Site at NPS.gov – official site

- "Andersonville: Prisoner of War Camp", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: American Civil War prison camps

- "WWW Guide to Civil War Prisons" (2004)