Americus, Georgia

| Americus, Georgia | |

|---|---|

| City | |

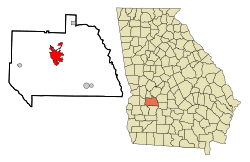

Location in Sumter County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 32°4′31″N 84°13′36″W / 32.07528°N 84.22667°WCoordinates: 32°4′31″N 84°13′36″W / 32.07528°N 84.22667°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Sumter |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10.7 sq mi (27.6 km2) |

| • Land | 10.5 sq mi (27.1 km2) |

| • Water | 0.2 sq mi (0.5 km2) |

| Elevation | 479 ft (146 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 17,041 |

| • Density | 1,590/sq mi (616.3/km2) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) |

| ZIP codes | 31709, 31710, 31719 |

| Area code(s) | 229 |

| FIPS code | 13-02116[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0331037[2] |

| Website |

www |

Americus is a city in Sumter County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 17,041.[3] Americus is the home of Habitat for Humanity's international headquarters, the famous Windsor Hotel (from 1892), The Fuller Center for Housing international headquarters, The Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving,[4] Glover Foods and many more well-known organizations.

The city is the county seat of Sumter County.[5] Americus is the principal city of the Americus Micropolitan Statistical Area, a micropolitan area that covers Schley and Sumter counties[6] and had a combined population of 36,966 at the 2000 census.[1]

Geography

Americus is located at 32°4′31″N 84°13′36″W / 32.07528°N 84.22667°W (32.075221, -84.226602).[7]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.7 square miles (28 km2), of which, 10.5 square miles (27 km2) of it is land and 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2) of it (1.87%) is water.

Climate

| Climate data for Americus, Georgia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

62 (17) |

69 (21) |

76 (24) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

91 (33) |

86 (30) |

78 (26) |

69 (21) |

60 (16) |

76.1 (24.5) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 34 (1) |

37 (3) |

43 (6) |

49 (9) |

58 (14) |

66 (19) |

69 (21) |

69 (21) |

63 (17) |

53 (12) |

44 (7) |

37 (3) |

51.8 (11) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 4.61 (117.1) |

4.53 (115.1) |

5.08 (129) |

3.74 (95) |

3.23 (82) |

4.17 (105.9) |

4.88 (124) |

4.13 (104.9) |

3.78 (96) |

2.36 (59.9) |

3.78 (96) |

4.65 (118.1) |

48.94 (1,243.1) |

| Source: [8] | |||||||||||||

History

|

Americus Historic District | |

|

Windsor Hotel façade | |

| Location | Irregular pattern along Lee St. with extensions to Dudley St., railroad tracks, Rees Park, and Glessner St. (original), E. Church St. and Oak Grove Cemetery (increase), Americus, Georgia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 32°4′2″N 84°14′5″W / 32.06722°N 84.23472°W |

| Built | 1859 (increase) |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Classical Revival, Late Gothic Revival, Romanesque |

| NRHP Reference # |

76000648 (original) 79003319[9] (increase) |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 1, 1976 |

| Boundary increase | September 3, 1979 |

Early years

Americus was founded by General John Americus Smith. While out on a scouting mission with his men, he noticed that there was a great deal of distance between two cities. He decided that he would come back and purchase land to build on in 1825. As he built on his land, his plantation grew very large in cotton production. Soon, more and more people started moving to the location until in 1832 the town of Americus was founded. Gen John's plantation was a huge part in helping Americus grow and providing income for the town. Gen John would later pass of the flu in 1868 at the age of 62 years. After his death his plantation was divided up into sections and auctioned off to different farmers that had now moved into the area.[10]

For its first two decades, Americus was a small courthouse town. The arrival of the railroad in 1854 and, three decades later, local attorney Samuel H. Hawkins' construction of the only privately financed railroad in state history, made Americus the eighth largest city in Georgia into the 20th century. It was known as the "Metropolis of Southwest Georgia," a reflection of its status as a cotton distribution center. In 1890, Georgia's first chartered electric street car system went into operation in Americus. One of its restored cars is on permanent display at the Lake Blackshear Regional Library, a gift from the Robert T. Crabb family who acquired the street car in the 1940s.

The town was already graced with an abundance of antebellum and Victorian architecture when local capitalists opened the Windsor Hotel in 1892. A five-story Queen Anne edifice, it was designed by a Swedish architect, Gottfried L. Norrman, in Atlanta. Vice-President Thomas R. Marshall gave a speech from the balcony in 1917 and soon to be New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke in the dining room in 1928.

On January 1, 1976, the city center was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Americus Historic District. The district boundaries were extended in 1979.[9]

Into the 20th century

For the local minority community, Rev. Dr. Major W. Reddick established the Americus Institute (1897–1932). Booker T. Washington was a guest speaker there in May 1908. Rev. Alfred S. Staley was responsible for locating the state Masonic Orphanage in Americus, which served its function from 1898 to 1940. Both men engineered the unification of the General Missionary Baptist Convention of Georgia in 1915, the former as president and the latter as recording secretary. The public school named in honor of A.S. Staley was designated a National School of Excellence in 1990.

Two other institutions of higher learning were also established in Americus, the Third District Agricultural and Mechanical School in 1906 (now Georgia Southwestern State University), and the South Georgia Trade and Vocational School in 1948 (now South Georgia Technical College). South Georgia Technical College is located on the original site of Souther Field.

In World War I, an Army Air Service training facility, Souther Field (now Jimmy Carter Regional Airport), was commissioned northeast of the city limits. Charles A. Lindbergh, the "Lone Eagle," bought his first airplane and made his first solo flight there during a two-week stay in May 1923. Recommissioned for World War II, Souther Field was used for RAF pilot training (1941–1942)[11] as well as US pilot training before ending the war as a German prisoner-of-war camp. The town was incorporated in 1832, and the name Americus was picked out of a hat.[12]

- Shoeless Joe Jackson served as the field manager for the local baseball team after his banishment from professional baseball. A plaque at Thomas Bell Stadium commemorates his contribution to the local baseball program.

Americus and the Civil Rights Movement

Koinonia Farm, an interracial Christian community, was organized near Americus in 1942. Founder Clarence Jordan was a mentor to Millard and Linda Fuller, who founded Habitat for Humanity International at Koinonia in 1976 before moving into Americus the following year. In 2005, they founded The Fuller Center for Housing, also in Americus. Koinonia Farm is currently located southwest of Americus on Hwy. 49.

The Civil Rights Era in Americus was a time of great turmoil; violent opposition to Koinonia by racist elements led to the bombing of a store uptown in 1957. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spent a weekend in the courthouse jail in 1961, after an arrest in Albany. The "Sumter Movement" to end racial segregation was organized and led by Rev. Joseph R. Campbell in 1963. As a direct result, two Georgia laws were subsequently declared unconstitutional by a federal tribunal meeting in Americus. Color barriers were first removed in 1965 when J.W. Jones and Henry L. Williams joined the Americus police force. Lewis M. Lowe was elected as the first black city councilman ten years later. With their election in 1995, Eloise R. Paschal and Eddie Rhea Walker broke the gender barrier on the city's governing body.

In 1971, the city was featured in a Marshall Frady article, "Discovering One Another in a Georgia Town", in Life magazine. The portrayal of the city's school integration was relatively benign, especially considering the community's history of troubled race relations. Americus' nadir in this respect had occurred in 1913, when a young black man named Will Redding was lynched by a white mob. A group of young African Americans were standing on the corner of Cotton Avenue and Lamar street. One of those men was Will Redding. Police chief Barrow ordered them to move away from the corner, all complied except Redding. The chief tried to arrest Redding and a struggle ensued. Will Redding was then hit with the Chief's gun, afterwards, Redding grabbed the gun and shot the police chief. Will Redding was then chased down, shot, and put in jail. An angry mob went into the jail and tore down the door to Redding's cell. When the door was completely torn down, the mob dragged Will Redding out onto Forsyth street and beat him to death using crow bars and hammers.[13]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 3,259 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,635 | 11.5% | |

| 1890 | 6,398 | 76.0% | |

| 1900 | 7,674 | 19.9% | |

| 1910 | 8,063 | 5.1% | |

| 1920 | 9,010 | 11.7% | |

| 1930 | 8,760 | −2.8% | |

| 1940 | 9,281 | 5.9% | |

| 1950 | 11,389 | 22.7% | |

| 1960 | 13,472 | 18.3% | |

| 1970 | 16,091 | 19.4% | |

| 1980 | 16,120 | 0.2% | |

| 1990 | 16,512 | 2.4% | |

| 2000 | 17,013 | 3.0% | |

| 2010 | 17,041 | 0.2% | |

| Est. 2015 | 16,028 | [14] | −5.9% |

As of the census[1] of 2000, there were 17,013 people, 6,374 households, and 4,149 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,623.1 people per square mile (626.8/km²). There were 7,053 housing units at an average density of 672.9 per square mile (259.8/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 39.05% White, 58.26% African American, 0.23% Native American, 0.86% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.90% from other races, and 0.69% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.49% of the population.

There were 6,374 households out of which 32.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.2% were married couples living together, 27.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.9% were non-families. 29.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.52 and the average family size was 3.14.

In the city the population was spread out with 28.0% under the age of 18, 14.1% from 18 to 24, 26.1% from 25 to 44, 18.0% from 45 to 64, and 13.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females there were 79.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 70.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $26,808, and the median income for a family was $32,132. Males had a median income of $27,055 versus $20,169 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,168. About 23.4% of families and 27.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 44.1% of those under age 18 and 19.8% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Largest employers

According to the City's 2009 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[16] the largest employers in the area are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sumter County Schools | 950 |

| 2 | Eaton Cooper Lighting | 600 |

| 3 | Habitat for Humanity | 400 |

| 4 | Wal-Mart | 399 |

| 5 | Phoebe Sumter Medical Center | 396 |

| 6 | Magnolia Manor | 375 |

| 7 | Georgia Southwestern State University | 280 |

| 8 | Southern Star Community Services | 253 |

| 9 | Sumter County | 235 |

| 10 | City of Americus | 195 |

Education

Sumter County School District

The Sumter County School District holds grades pre-school to twelfth, which consist of one primary school and one elementary school, two middle schools, and two high schools.[17] The district has 353 full-time teachers and over 5,774 students.[18]

Elementary schools

- Sumter County Elementary School

- Sumter County Primary School

- Sarah Cobb Elementary School

Middle schools

- Sumter County Middle School

High schools

- Americus Sumter County High South

Private education

- Southland Academy- Southland currently has 600 students from 4 year old kindergarten through 12 grade. It is a part of the Georgia Independent Schools Association (GISA).

Higher education

- Georgia Southwestern State University- Main Campus[19]

- South Georgia Technical College-Main Campus[20]

All schools and colleges are accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS).

Tornado

Americus was hit by a tornado around 9:15 P.M. on March 1, 2007. The EF-3 tornado was up to one mile wide, and carved a 38-mile path of destruction through the city and surrounding residential areas.[21] It destroyed parts of Sumter Regional Hospital, forcing the evacuations of all of the patients there. There were two fatalities at a Hudson Street residence near the hospital; all SRH patients were evacuated safely. The hospital, however, faced major reconstruction issues and was eventually torn down. A new hospital, Phoebe Sumter, opened at a new location on the corner of US 19 and Highway 280 in December 2011.

Georgia Governor Sonny Perdue said, "It was worse that [sic] I had feared. The hospital was hit, but the devastation within the area of Sumter County and Americus was more than I imagined. The businesses around the hospital are totally destroyed. Power is still not restored in many places. It's just a blessing frankly that we didn't have more fatalities than we did."[22] Over 500 homes were affected, with around 100 completely destroyed. Several businesses throughout the town were seriously damaged or destroyed as well. Among the businesses suffering major damage were Winn Dixie supermarket, Wendy's, Zaxby's, McDonald's, Domino's Pizza, and several local businesses. The Winn Dixie was completely destroyed. Domino's Pizza has since reopened, as well as Winn Dixie.

President George W. Bush visited the area on March 3, calling what he saw "tough devastation."

Notable people

Prominent citizens of Americus include:

- Griffin Bell

- Gen. Howell Cobb

- Gen. Philip Cook

- Charles F. Crisp

- Charles R. Crisp

- Dr. Cassandra Pickett Durham

- Lonne Elder III

- Millard Fuller

- Chan Gailey

- Victor Green

- Kent Hill

- George Hooks

- Alonzo Jackson

- Godfrey Thomas "Tommy" Knight, Jr.

- Joanna Moore

- Ruby Muhammad

- Leonard Pope

- Dan Reeves

- Mo Sanford

- Angel Martino

- Eddie Jackson

- Otis Leverette

Baseball in Americus

There have been eight Minor league teams that have represented the city of Americus during 20 seasons spanning 1906–2002. Since classification of the minors began, seven of them have been labeled as class D loops and one played in an independent league. Several ballplayers for Americus teams subsequently played in the Major Leagues.

Tourism

- Georgia Rural Telephone Museum - Leslie

- Georgia Veterans State Park - Lake Blackshear

- Jimmy Carter National Historic Site - Plains

References

- 1 2 3 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_SF1_GCTP2.ST13&prodType=table

- ↑ "Rosalynn Carter Institute".

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ MICROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS AND COMPONENTS Archived June 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Office of Management and Budget, 2007-05-11. Accessed 2008-07-27.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "U.S. Climate Data". U.S. Climate Data. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- 1 2 National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Hellmann, Paul T. (May 13, 2013). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Routledge. p. 216. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ Gilbert S. Guinn, The Arnold Scheme: British Pilots, The American South and the Allies Daring Plan, History Press, 2007

- ↑ Watson, Stephanie; Lisa Wojna (2008). Weird, Wacky, and Wild Georgia Trivia. Blue Bike Books. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-897278-44-4.

- ↑ Anderson, Alan (July 30, 2006). Remembering Americus Georgia: Essays on Southern Life. History Press (SC). pp. 73–74https://books.google.com/books?id=svf_7DV9i6UC&pg=PA129&lpg=PA129&dq=remembering+americus+georgia+essays&source=bl&ots=8fJVoP2Xbf&sig=Z4YA9QeYHCJoQkww6tZLuGRoLv4&hl=en&sa=X&ei=J64cVLmbAoGZyAS8lIHYDg&ved=0CCwQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=remembering%20americus%20georgia%20essays&f=false. ISBN 9781596291317.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "City of Americus 2009 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ↑ Georgia Board of Education, Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ↑ School Stats, Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ↑ Georgia Southwestern State University, Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ↑ South Georgia Technical College Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ↑ "PRELIMINARY DAMAGE REPORT FOR 1 MARCH 2007 TORNADO OUTBREAK". Archived from the original on 2009-02-11.

- ↑ WALb.com News, Weather and Sports for Albany, Valdosta and Thomasville. Leading the way for South Georgia. | Sumter hospital shows tornado's worst punch

- ↑ http://www.americusga.gov/#!area-attractions/cmuv

External links

- City website

- Community website

- Americus (in the New Georgia Encyclopedia)

- The Americus Newsletter

- Americus Sumter Chamber of Commerce

- South Georgia Historic Newspapers Archive, Digital Library of Georgia

- Americus Movement, Civil Rights Digital Library