Anaplasmosis

| Anaplasmosis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| MeSH | D000712 |

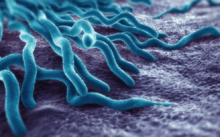

Anaplasmosis is a disease caused by a rickettsial parasite of ruminants, Anaplasma spp. The microorganism is gram-negative[1] and occurs in the red blood cells. It is transmitted by natural means through a number of haematophagous species of ticks. Anaplasmosis can also be transmitted by the use of surgical, dehorning, castration, and tattoo instruments and hypodermic needles that are not disinfected between uses.

Although the term is often associated with animal infection, it is also used to describe infection in humans.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Anaemia may be severe and result in cardiovascular changes such as an increase in heart rate. Blood in the urine may occur due to the lysis of red blood cells. General systemic signs such as diarrhea, anorexia and weight loss may also be present. A blood smear stained with Giemsa should be observed for identification of infected red blood cells and will allow definitive diagnosis.[3]

Other symptoms of this disease could include: Fever, Headache, Muscle pain, Malaise, Chills, Nausea, and/or Abdominal pain, Cough, and Confusion, and even a Rash which may be rare with this infection.[4]

Prevention

Vaccines against anaplasmosis are available. Carrier animals should be eliminated from flocks. Tick control may also be useful although it can be difficult to implement.[3]

Treatment

Treatment usually involves a prescription of doxycycline (a normal dose would be 100 mg every 12 hours for adults or a similar class of antibiotics. Oxytetracycline and imidocarb have also been shown to be effective. Supportive therapy such as blood products and fluids may be necessary.[3]

The best time to start a doxycycline treatment is three days after the rash clears up on the patient. A common cycle of this antibiotic will last for one to two weeks, depending on the severity of the patients condition. It is not completely uncommon for some patients to experience mild symptoms such as, headache, fatigue, or a general feeling of discomfort for up to several weeks after treatment.[4]

Epidemiology

In the United States, anaplasmosis is notably present in the south and west where the tick hosts Ixodes spp. are found. It is also a seemingly increasing antibody in humans in Europe.[1] Although vaccines have been developed, none are currently available in the United States. Early in the 20th century, this disease was considered one of major economic consequence in the western United States. In the 1980s and 1990s, control of ticks through new acaricides and practical treatment with prolonged-action antibiotics, notably tetracycline, has led to the point where the disease is no longer considered a major problem.

Cases of coinfection with tick-borne microorganisms are being increasingly reported in the last decade,[5][6][7] perhaps explaining the variable manifestations and clinical responses noted in some patients with tick-transmitted diseases. In such clinical settings, laboratory testing for coinfection is indicated to ensure that appropriate antimicrobial treatment is given.

In 2005, Anaplasma ovis was found in reindeer populations in Mongolia.[8] This pathogen and its associated syndrome (characterized by lethargy, fever and pale mucous membranes) was previously only observed in wild sheep and goats in the region, and is the first observed event of A. ovis in reindeer.

In Australia, bovine anaplasmosis, caused by Anaplasma marginale, is only found in the northern and eastern parts of Australia where the cattle tick is present. It was probably introduced as early as 1829 by cattle from Indonesia infested with the cattle tick Boophilus microplus.[9]

Notable cases

On July 30, 2009, David Letterman announced that he had been infected with anaplasmosis. He believes he was most likely bitten by an infected tick while camping with his 5-year-old son in their tree house.

References

- 1 2 Hartelt, Kathrin; Oehme, Rainer; Frank, Henning; Brockmann, Stefan O.; Hassler, Dieter; Kimmig, Peter (2004-04-01). "Pathogens and symbionts in ticks: prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Ehrlichia sp.), Wolbachia sp., Rickettsia sp., and Babesia sp. in Southern Germany". International Journal of Medical Microbiology Supplements. Proceedings of the VII International Potsdam Symposium on Tick-Borne Diseases. 293, Supplement 37: 86–92. doi:10.1016/S1433-1128(04)80013-5.

- ↑ "CDC—Anaplasmosis: Questions and Answers | Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases". Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- 1 2 3 Anaplasmosis reviewed and published by WikiVet, accessed 10 October 2011.

- 1 2 "Anaplasmosis". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ Paul D. Mitchell,* Kurt D. Reed, and Jeanie M. Hofkes “Immunoserologic Evidence of Coinfection with Borrelia burgdorferi, Babesia microti, and Human Granulocytic Ehrlichia Species in Residents of Wisconsin and Minnesota” // Journal Of Clinical Microbiology, Mar. 1996, p. 724–727.

- ↑ Micha Loebermann, Volker Fingerle, Matthias Lademann, Carlos Fritzsche, Emil C. Reisinger “Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophilum Coinfection” // Emerging Infectious Diseases, Feb, 2006.

- ↑ Walid MS, Ajjan M, Patel N: Borreliosis And Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis Coinfection With Positive Rheumatoid Factor And Monospot Test: Case-Report. The Internet Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007; Volume 6, Number 1.

- ↑ Haigh J, Gerwing V, Erdenebaatar J, Hill J. 2008. A novel clinical syndrome and detection of Anaplasma ovis in Mongolian reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). J Wildlife Dis 44(3): 569–577.

- ↑ "bovine anaplasmosis". Tick fever. Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Queensland Government. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

External links

- CFIA Animal Disease Information