Aortic arches

| Aortic arches | |

|---|---|

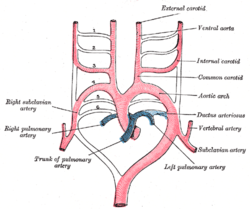

Scheme of the aortic arches and their destination. | |

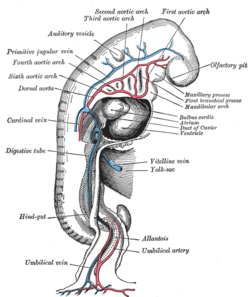

Profile view of a human embryo estimated at twenty or twenty-one days old. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Arteriae arcuum pharyngeorum |

| Code | TE E4.0.3.5.0.3.3 |

The aortic arches or pharyngeal arch arteries (once referred to as branchial arches in human embryos) are a series of six paired embryological vascular structures which give rise to the great arteries of the neck and head. They are ventral to the dorsal aorta and arise from the aortic sac.

The aortic arches are formed sequentially within the pharyngeal arches and initially appear symmetrical on both sides of the embryo,[1] but then undergo a significant remodelling to form the final asymmetrical structure of the great arteries.[1][2]

Specific arches

Arches 1 and 2

The first and second arches disappear early, remnant of the 1st arch forms part of the maxillary artery (branch of external carotid art.) but the dorsal end of the second gives origin to the stapedial artery, a vessel which atrophies in humans but persists in some mammals. It passes through the ring of the stapes and divides into supraorbital, infraorbital, and mandibular branches which follow the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve. The infraorbital and mandibular arise from a common stem, the terminal part of which anastomoses with the external carotid.

On the obliteration of the stapedial artery this anastomosis enlarges and forms the internal maxillary artery, and the branches of the stapedial artery are now branches of this vessel.

The common stem of the infraorbital and mandibular branches passes between the two roots of the auriculotemporal nerve and becomes the middle meningeal artery; the original supraorbital branch of the stapedial is represented by the orbital twigs of the middle meningeal.

Note that the external carotid buds from the horns of the aortic sac left behind by the regression of the first two arches.

Arch 3

The third aortic arch constitutes the commencement of the internal carotid artery, and is therefore named the carotid arch. Common carotid artery and proximal internal carotid artery.

Arch 4

The fourth right arch forms the right subclavian as far as the origin of its internal mammary branch; while the fourth left arch constitutes the arch of the aorta between the origin of the left carotid artery and the termination of the ductus arteriosus.

Arch 5

The fifth arch either never forms or forms incompletely and then regresses.[2]

Arch 6

The proximal part of the sixth right arch persists as the proximal part of the right pulmonary artery while the distal section degenerates; The sixth left arch gives off the left pulmonary artery and forms the ductus arteriosus; this duct remains pervious during the whole of fetal life, but then closes within the first few days after birth due to increased O2 concentration. Oxygen concentration causes the production of bradykinin which causes the ductus to constrict occluding all flow. Within 1–3 months, the ductus is obliterated and becomes the ligamentum arteriosum.

The ductus arteriosus connects at a junction point that has a low pressure zone (commonly called Bernoulli's principle) created by the inferior curvature (inner radius) of the artery. This low pressure region allows the artery to receive (siphon) the blood flow from the pulmonary artery which is under a higher pressure. However, it is extremely likely that the major force driving flow in this artery is the markedly different arterial pressures in the pulmonary and systemic circulations due to the different arteriolar resistances.

His showed that in the early embryo the right and left arches each gives a branch to the lungs, but that later both pulmonary arteries take origin from the left arch.

Great arteries anomalies

Most defects of the great arteries arise as a result of persistence of aortic arches that normally should regress or regression of arches that normally shouldn't.

- Aberrant subclavian artery; with regression of the right aortic arch 4 and the right dorsal aorta, the right subclavian artery has an abnormal origin on the left side, just below the left subclavian artery. To supply blood to the right arm, this forces the right subclavian artery to cross the midline behind the trachea and esophagus, which may constrict these organs, although usually with no clinical symptoms.

- A double aortic arch; occurs with the development of an abnormal right aortic arch in addition to the left aortic arch, forming a vascular ring around the trachea and esophagus, which usually causes dificutly breathing and swallowing. Occasionally, the entire right dorsal aorta abnormally persists and the left dorsal aorta regresses in which case the right aorta will have to arch across from the esophagus causing difficulty breathing or swallowing.

- Right-sided aortic arch

- Patent ductus arteriosus

- Coarctation of the aorta

Additional images

-

Diagram showing the origins of the main branches of the carotid arteries.

See also

References

- 1 2 Hiruma, Tamiko; Nakajima, Yuji; Nakamura, Hiroaki (2002-07-01). "Development of pharyngeal arch arteries in early mouse embryo". Journal of Anatomy. 201 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00071.x. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1570898

. PMID 12171473.

. PMID 12171473. - 1 2 Bamforth, Simon D.; Chaudhry, Bill; Bennett, Michael; Wilson, Robert; Mohun, Timothy J.; Van Mierop, Lodewyk H.S.; Henderson, Deborah J.; Anderson, Robert H. (2013-03-01). "Clarification of the identity of the mammalian fifth pharyngeal arch artery". Clinical Anatomy. 26 (2): 173–182. doi:10.1002/ca.22101. ISSN 1098-2353.

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

- Embryology at Temple Heart98/heart97b/sld041

- Diagram at University of Michigan

- hednk-008—Embryo Images at University of North Carolina