Bahá'í Faith in Germany

Though mentioned in the Bahá'í literature in the 19th century, the Bahá'í Faith in Germany begins in the early 20th century when two emigrants to the United States returned on prolonged visits to Germany bringing their newfound religion. The first Bahá'í Local Spiritual Assembly was established following the conversion of enough individuals to elect one in 1908.[1] After the visit of `Abdu'l-Bahá,[2] then head of the religion, and the establishing of many further assemblies across Germany despite the difficulties of World War I, elections were called for the first Bahá'í National Spiritual Assembly in 1923.[3] Banned for a time by the Nazi government and then in East Germany the religion re-organized and was soon given the task of building the first Bahá'í House of Worship for Europe.[4] After German reunification the community multiplied its interests across a wide range of concerns earning the praise of German politicians.[5][6] German Census data shows 5600 registered Bahá'ís in Germany in 2012.[7] But there might be much more who are not enrolled in the official community. The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 11743 Bahá'ís in 2005.[8]

First century

Early phase

| Part of a series on |

| Bahá'í Faith |

|---|

|

| Central figures |

| Key scripture |

| Institutions |

| History |

| People |

| Holy sites |

|

| Other topics |

|

Ibrahim George Kheiralla, an early Bahá'í from Lebanon, traveled through Germany in 1892 attempting to making a living but found no interest in his inventions and moved on to the United States in February, 1893.[9] There he managed to convert some individuals by 1895 (see Thornton Chase.) Following these conversions, some German emigrants became Bahá'ís as well. Two in particular traveled back to Germany: Edwin Fischer and Alma Knobloch. Dr. Edwin Fischer, a dentist, had emigrated in 1878 from Germany to New York City, became a Bahá'í there, and then returned to Stuttgart in 1905. Fisher used every opportunity, including talking with his patients, to mention the Bahá'í teachings, and in time a few Germans embraced the religion.[4][10] The other German Bahá'í, Alma Knobloch, became a Bahá'í in 1903, before Fischer, but arrived in Germany in 1907.[1] This small group of Bahá'ís began to organize and formed a Bahá'í Local Spiritual Assembly in 1908 and by 1909 began self-publishing pamphlets and letters and Bahá'í books including the Hidden Words and a history of the religion by Knobloch. The second spiritual assembly in Germany was founded in 1909 in Esslingen.

In the German Colony in Palestine, as part of the worldwide German diaspora, "Frau Doktor Fallscheer" was the family physician for the family of `Abdu'l-Bahá, son of the founder of the religion. Fallscheer later became a Bahá'í when she moved back to Germany by 1930.[11] Prominent early Bahá'í Louis George Gregory stayed at a hotel in the German Colony in Haifa during his Bahá'í pilgrimage[12] to Palestine in the spring of 1911 and on his return trip visited in Germany at the request of `Abdu'l-Bahá[13] in the fall of 1912.[14]

`Abdu'l-Bahá's visit to Germany

`Abdu'l-Bahá, then head of the religion, visited Germany for 8 days in 1913, including visiting Stuttgart, Esslingen and Bad Mergentheim.[2] During this visit he spoke to a youth group as well as a gathering of Esperantists.[15] In less than a decade Bahá'í sources state there were some 300 Bahá'ís in Germany by the time of `Abdu'l-Bahá's arrival.[16] See `Abdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West.

`Abdu'l-Bahá wrote a series of letters, or tablets, to the followers of the religion in the United States in 1916-1917; these letters were compiled together in the book Tablets of the Divine Plan. The seventh of the tablets mentioned European regions and was written on April 11, 1916, but was delayed in being presented in the United States until 1919—after the end of the First World War and the Spanish flu. The seventh tablet was translated and presented on April 4, 1919, and published in Star of the West magazine on December 12, 1919 and mentioned Germany.[17] He says:

"In brief, this world-consuming war has set such a conflagration to the hearts that no word can describe it. In all the countries of the world the longing for universal peace is taking possession of the consciousness of men. There is not a soul who does not yearn for concord and peace. A most wonderful state of receptivity is being realized.… Therefore, O ye believers of God! Show ye an effort and after this war spread ye the synopsis of the divine teachings in the British Isles, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia, Italy, Spain, Belgium, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, Portugal, Rumania, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Greece, Andorra, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, San Marino, Balearic Isles, Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, Crete, Malta, Iceland, Faroe Islands, Shetland Islands, Hebrides and Orkney Islands."[18]

`Abdu'l-Bahá praised the German Bahá'ís - "individuals...endued with perceptive eyes and attentive ears" were "attracted to the principles of the oneness of mankind" and treated "all the peoples and kindreds of the earth in a spirit of concord and fellowship." He predicted Germany will "surpass all other regions" and "lead all the nations and peoples of Europe spiritually."[19] Shoghi Effendi, head of the religion after the death of `Abdu'l-Bahá, continued commentary about Germany and its Bahá'ís; he wrote that during the Nazi government the German Bahá'ís demonstrated that they were the "great-hearted, indefatigable, much admired German Bahá'í community".[20]

World War I

As World War I was becoming more widespread in its ramifications, the Bahá'ís pursued other courses of action. In 1916 a plaque was raised to honor `Abdu'l-Bahá's visit at Bad Mergentheim.[21] On May 23, 1916, Austrian Franz Pöllinger learned of the religion while staying in Stuttgart and on returning to Austria had a prominent role in the growth of the religion there.[22][23] When the United States entered the war, individuals from there, as Fischer[4] and Knobloch,[1] had to leave Germany and both returned to the United States. On return to the US Fischer went to the Los Angeles area and Knobloch went to New York. In a wave of anti-German sentiment (see German American internment for similar issues a generation later) Fischer was caught up in charges of espionage for Germany which were dismissed.[24] As Germany was allied with the Ottoman Empire, the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of World War I played an important role with the Bahá'ís in Palestine - particularly the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918. As a direct result of the events of the battle, `Abdu'l-Bahá was rescued after death threats were made against him in case the Ottoman side was to lose (events in which Wellesley Tudor Pole played a significant part.)[25][26]

Post-War closing

After WWI, the national Bahá'í community organized a German Bahá'í Publishing Trust[4] and in 1920 Adelbert Mühlschlegel became a Bahá'í, and later appointed as a Hand of the Cause, individuals who have been considered to have achieved a distinguished rank in service to the religion. He was the first of three believers who decisively influenced the German Bahá'ís.[22] As with other German emigrants who converted to the religion, Siegfried Schopflocher who was born in Germany, as an Orthodox Jew, sought out a wider unity and found the Bahá'í Faith while in Canada in the summer of 1921; he was also later appointed a Hand of the Cause.[27] `Abdu'l-Bahá's last tablet before his death was addressed to the Bahá'ís in Stuttgart in November 1921.[28]

Inter-war period

In 1921 a new magazine Sun of Truth was first published as one of five Bahá'í journals produced by German Bahá'ís through the 1920s.[19] It contained newly translated Bahá'í literature and news from the Bahá'í community around the world.[4]

In 1923 the first Bahá'í National Spiritual Assemblies were elected "where conditions are favorable and the number of the friends has grown and reached a considerable size".[3] Along with India and the British Isles, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Germany and Austria was first elected in that year.[29] In 1925 there were 95 delegates who performed the election.[3] A 1925 list of local Bahá'í Centers mentions no less than 26 in Germany, compared to three in England and two in Switzerland.[19] In late 1926[30] and again in 1929[31] widely traveled Martha Root spoke in most German universities and technical colleges. Eugen Schmidt, the second of the three believers who decisively influenced the German Bahá'ís, became a Bahá'í and was elected a member of the National Spiritual Assembly of Germany from 1932 for many years and served as chairman in the decisive years of re-building after World War II.[22]

Among the Bahá'ís to visit Germany were Amelia Collins, Marion Jack and Louisa Mathew Gregory, wife of Louis George Gregory.[32] Another Bahá'í with links to Germany was Robert Sengstacke Abbott whose adoptive father was German and, through his family connection, he kept in contact with his family in Germany.[33] In 1930 the national convention included delegates from Stuttgart, Rostock, Hamburg, Schwerin, Karlsruhe, Göppingen, Bissingen, and from Vienna.[34] The 1931 national assembly included four women and five men.[35] In 1935 Shoghi Effendi, then head of the religion, re-organized the German community to cover Austria as well so they shared a regional national assembly.[36]

Nazi period

During the early Nazi period Bahá'ís had general freedom; May Maxwell, wife of William Sutherland Maxwell, was still able to travel through Germany in 1936,[37] though the plaque commemorating `Abdu'l-Bahá's visit had been taken down.[21] By 1937 however, Heinrich Himmler signed an order disbanding the Bahá'í Faith's institutions in Germany[4] because of its 'international and pacifist tendencies'.[38] In 1939 and in 1942 there were sweeping arrests of former members of the National Spiritual Assembly. In May 1944 there was a public trial in Darmstadt at which Dr. Hermann Grossmann was allowed to defend the character of the religion but the Bahá'ís were instead heavily fined and its institutions continued to be disbanded. However for this service and others, Grossmann was ranked as the third of the three believers who decisively influenced the German Bahá'ís.[22]

After the Nazi period

Following the fall of Nazi Germany, an American Bahá'í, John C. Eichenauer who was a medic of the 100th Infantry division then at Geislingen started searching for the Bahá'í community in Stuttgart. He drove through Stuttgart looking and asking for Bahá'ís and was able to find an individual by nightfall/curfew. The next day saw the first meeting of Bahá'ís since their disbandment in 1937. Two other American Bahá'ís, Bruce Davison and Henry Jarvis, in Frankfurt and Heidelberg respectively, also connected with the Bahá'í community in Germany. At the beginning of the partition of Germany there were about 150 German Bahá'ís in the American section and they became registered with the American authorities. The National Spiritual Assembly was re-elected in 1946[6] and by 1950 there were 14 Local Spiritual Assemblies:[39]

| Bergstrasse | Darmstadt | Esslingen | Frankfurt | Göppingen | Hamburg | Heidelberg |

| Karlsruhe | Leipzig | Nürnberg | Plochingen | Schwerin | Stuttgart | Wiesbaden |

and smaller Bahá'í communities in 27 cities.[40]

However, in Soviet controlled East Germany, the Bahá'í Faith was again disbanded in 1948.[4] In West Germany, by 1954 there were reports of large growth in the religion,[41] and from 1951 to 1966 philately stationery and a "Cinderella stamp" religious stationery were produced in West Germany.[42]

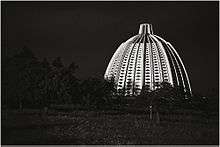

House of Worship

The construction of the Bahá'í House of Worship in Langenhain near Frankfurt, began in 1952.[4] Hand of the Cause Amelia Collins represented the Bahá'í International Community at the groundbreaking 20 November 1960. Designated as the "Mother Temple of Europe",[43] it was dedicated in 1964 by Hand of the Cause Ruhiyyih Khanum, representing the first elected Universal House of Justice.[44]

Development in West Germany

By 1963 the list of local assemblies was:

Isolated Bahá'ís were found in an additional 86 locations.[45]

West German Bahá'ís were given the responsibility of trying to strengthen the Bahá'í community in Russia in 1963. During the 1960s and 1970s, a small number of Bahá'ís visited the Soviet Union as tourists but no attempt was made to promulgate the religion. In 1986 Friedo and Shole Zölzer and Karen Reitz from Germany traveled into the Soviet Union but remained for only short periods of time.[46] Continuing in the 1980s and into the 1990s the Bahá'í Esperanto-League began to prosper especially in West Germany. One reason behind this was that Esperanto had acquired the reputation of being an "entrance ticket" to countries behind the Iron Curtain,[47] countries to which the Bahá'í Faith had had little access during the preceding decades (the first post-World War II Bahá'í know to pioneer to Russia was in 1979.)[46]

Reunion

Following the German reunification in 1989-91 the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany handed down a judgement affirming the status of the Bahá'í Faith as a religion in Germany.[48] Continued development of youth oriented programs included the Diversity Dance Theater (see Oscar DeGruy) which traveled to Albania in February 1997.[49] Udo Schaefer et al.'s 2001 Making the Crooked Straight was written to refute a polemic supported by the Evangelical Church in Germany written in 1981.[50][51][52] Since its publication the Evangelical Church in Germany has revised its own relationship to the German Bahá'í Community.[53] Former member of the federal parliament Ernst Ulrich von Weizsaecker commended the ideas of the German Bahá'í community on social integration, which were published in a statement in 1998,[5] and Chancellor Helmut Kohl sent a congratulatory message to the 1992 ceremony marking the 100th Anniversary of the Ascension of Bahá'u'lláh.[6]

Multiplying interests

Since its inception the religion has had involvement in socio-economic development beginning by giving greater freedom to women,[54] promulgating the promotion of female education as a priority concern,[55] and that involvement was given practical expression by creating schools, agricultural coops, and clinics.[54] The religion entered a new phase of activity when a message of the Universal House of Justice dated 20 October 1983 was released.[56] Bahá'ís were urged to seek out ways, compatible with the Bahá'í teachings, in which they could become involved in the social and economic development of the communities in which they lived. World-wide in 1979 there were 129 officially recognized Bahá'í socio-economic development projects. By 1987, the number of officially recognized development projects had increased to 1482. Nearing the century mark of the Bahá'í community in Germany, the Bahá'ís in Germany have begun efforts in diverse fields of interest. An estimated 500,000 people visited the Bahá'í pavilion at the Hanover Expo 2000. The 170 square-meter Bahá'í exhibit, hosted by the Bahá'í International Community and the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Germany, featured development projects in Colombia, Kenya and Eastern Europe that illustrated the importance of grassroots capacity-building, the advancement of women, and moral and spiritual values in the process of social and economic development.[57] The German community organized a national Bahá'í Choir in 2001 which tours various events in Germany and Europe.[58] In 2002 the director of the Ernst Lange-Institute for Ecumenical Studies held a meeting under the auspices of the German Federal Environment Ministry titled "Orientation dialogue of religions represented in Germany on environmental politics with reference to the climate issue" for the interfaith community including the Bahá'ís.[59] In 2005 former federal Minister of the Interior, Otto Schily, praised the contributions of German Bahá'ís to the social stability of the country, noting "It is not enough to make a declaration of belief. It is important to live according to the basic values of our constitutional state, to defend them and make them secure in the face of all opposition. The members of the Bahá'í Faith do this because of their faith and the way they see themselves."[5] However the Bahá'ís have been excluded from other dialogues on religious issues.[60] In 2007 a new memorial was unveiled replacing the one that had been taken down in Bad Mergentheim during Nazi Germany.[21] Bahá'ís from much of Europe were among the more than 4,600 people who gathered in Frankfurt for the largest ever Bahá'í conference in Germany in February 2009.[61]

Demographics

A 1997-8 estimate is of 4000 Bahá'ís in Germany (40 in Hannover).[6] In 2002 there were 106 Local Spiritual Assemblies.[5] The 2007-8 German Census using sampling estimated 5-6,000 Bahá'ís in Germany.[62] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 11,743 Bahá'ís.[63]

Artists

Among the better known Bahá'í artists of Germany are:

- Peter Held - Composer pianist.[64]

- Parisa Badiyi - violinist and educator[65]

- Brigitte Schirren - textiles[66]

- Hans J. Knospe - photopoetry[67]

- Anne Bahrinipour - painting, sculpture[68]

Prophecies regarding Germany

The writings of Bahá'u'lláh and `Abdu'l-Bahá in the late 19th century and early 20th century contain some prophecies regarding Germany. The first mention related to Germany in the Bahá'í Faith is when the founder of the religion, Bahá'u'lláh wrote in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas in 1873:

O banks of the Rhine! We have seen you covered with gore, inasmuch as the swords of retribution were drawn against you; and you shall have another turn. And We hear the lamentations of Berlin, though she be today in conspicuous glory.[69]

In 1912, shortly before visiting Germany, `Abdu'l-Bahá spoke of the increasing tensions in Europe:[70]

We are on the eve of the Battle of Armageddon referred to in the sixteenth chapter of Revelation... The time is two years hence, when only a spark will set aflame the whole of Europe... by 1917 kingdoms will fall and cataclysms will rock the earth.[71]

and in January 1920 he wrote:

The ills from which the world now suffers... will multiply; the gloom which envelops it will deepen. The Balkans will remain discontented. Its restlessness will increase. The vanquished Powers will continue to agitate. They will resort to every measure that may rekindle the flame of war.[72]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Mooman, Moojan (2004). Peter Smith, ed. Bahá'ís in the West. Kalimat Press. pp. 63–109. ISBN 1-890688-11-8.

- 1 2 Balyuzi, H.M. (2001). `Abdu'l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh (Paperback ed.). Oxford, UK: George Ronald. pp. 159–397. ISBN 0-85398-043-8.

- 1 2 3 Effendi, Shoghi (1974). Bahá'í Administration. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-166-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Geschichte (100 Jahre)". Official Website of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Germany. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Germany. Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- 1 2 3 4 International Community, Bahá'í (2005-05-31). "Senior government minister praises Baha'i contributions". Bahá'í World News Service.

- 1 2 3 4 Faridi, Ali (1998). "Bahá'i community in Hannover". Religions in Hannover. WCRP/Hannover. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ "Verschiedene Gemeinschaften / neuere religiöse Bewegungen". Religionen in Deutschland: Mitgliederzahlen (Membership of religions in Germany). REMID - the "Religious Studies Media and Information Service" in Germany. December 2012. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015.

- ↑ "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ↑ Haddad, Anton F. (1902). "An Outline of the Bahai Movement in the United States". Unpublished academic articles and papers. Bahá'í Library Online. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Bahá'í International Community; (photographs) Schramm, Alexander (2005-09-26). "German Baha'is celebrate 100 years". Bahá'í World News Service.

- ↑ Gail, Marzieh (1971). "'Abdu'l-Bahá: Portrayals from East and West". World Order. 06 (1): 29–41.

- ↑ G. Gregory, Louis (c. 1912). The Pilgrimage of Louis G. Gregory. Washington: R .L. Pendleton, 1997 edition printed by Alpha Services, Ferndale MI.

- ↑ N. Francis, Richard (1993). "Louis G. Gregory the Advancement of Racial Unity in America". Biographies. Bahá'í Library Online. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Morrison, Gayle (1982). To move the world : Louis G. Gregory and the advancement of racial unity in America. Wilmette, Ill: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-188-4.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. pp. 286–7. ISBN 0-87743-020-9.

- ↑ "Spirit of the Convention; Reports of Teachers". Bahá'í News (84): 4–5. June 1934.

- ↑ Abbas, `Abdu'l-Bahá (April 1919). Tablets, Instructions and Words of Explanation. Mirza Ahmad Sohrab (trans. and comments).

- ↑ `Abdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916-17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 43. ISBN 0-87743-233-3.

- 1 2 3 Hassall, Graham; Fazel, Seena (1998). "100 Years of the Bahá'í Faith in Europe". Bahá'í Studies Review. 08 (1998): 35–44.

- ↑ Savi, Julio (1994). "Germany, France, Italy, and Switzerland". Bahá'í Studies Review. 04 (1994).

- 1 2 3 German Baha'i News Service (2007-04-25). "German town re-erects monument". Bahá'í World News Service.

- 1 2 3 4 Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. The Bahá'í World. XVIII. Bahá'í World Centre. pp. 700–704, 800–802, 825. ISBN 0-85398-234-1.

- ↑ L. Root, Martha (2000). Tahirih the Pure. Kalimat Press. pp. With Martha, Marzeih Gail, pages xv–xxvii. ISBN 1-890688-04-5.

- ↑ Lee, Anthony; Richard Hollinger, eds. (1985). Circle of Peace: Reflections on the Baha'i Teachings. Kalimat Press. pp. Bahá'ís and American Peace Movements, pp. 3–20. ISBN 0-933770-48-0.

- ↑ Maude, Roderic; Maude, Derwent (1997). The Servant, the General and Armageddon. London, U.K.: George Ronald Pub Ltd. ISBN 0-85398-424-7.

- ↑ Ahmad Sohrab, Mirza (1947). The Story of the Divine Plan. Taking Place during, and immediately following World War I. New York: The New History Foundation, Digitally republished, East Lansing, Mi.: H-Bahai, 2004.

- ↑ C. van den Hoonaard, Will (1993-06-18). "Schopflocher, Siegfried". draft of "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith". Bahá'í Library Online. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi; Sara Louisa Blomfield, Lady (1922). The Passing of `Abdu'l-Bahá. Haifa: Rosenfeld Brothers.

- ↑ The Bahá'í Faith: 1844-1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Bahá'í Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953-1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 22 and 46.

- ↑ "Miss Martha Root in Northern Europe". Bahá'í News (19): 6–8. October 1927.

- ↑ "Miss Martha Root". Bahá'í News (32): 8. June 1929.

- ↑ International Community, Bahá'í (2005-08-03). "Baha'i group pays homage to a heroine". Bahá'í World News Service.

- ↑ Perry, Mark (1995-10-10). "Robert S. Abbott and the Chicago Defender: A Door to the Masses". Michigan Chronicle.

- ↑ "Annual Convention of German Bahá'ís". Bahá'í News (45): 3. October 1930.

- ↑ "Germany". Bahá'í News (53): 7. July 1931.

- ↑ "International News; Germany and Austria". Bahá'í News (90): 9. March 1935.

- ↑ "May Ellis Maxwell". Biographies. Bahá'í Library Online. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ Kolarz, Walter (1962). Religion in the Soviet Union. Armenian Research Center collection. St. Martin's Press. pp. 470–473 – via Questia (subscription required) .

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (1950). Bahá'í Faith, The: 1844-1950. Wilmette, IL: Bahá'í Publishing Committee.

- ↑ Communities existed in Auerbach bei Zwickau, Berlin, Heilbronn, Ebingen, Essen, Furtwangen, Garmisch, Geisenfeld, Giessen, Heilbronn, Immenstadt, Küssnach bei Waldshut, Lich, Lohme, Laubach, München, Murnau, Murrhardt, Bad Nauheim, Neuburg an der Donau, Oldenburg, Plochingen, Schwerin, Stuttgart, Wiesbaden, Pfullingen, and Talheim

- ↑ A Brown, Ramona (1954-05-02). "Haifa Notes". Pilgrims' notes. Bahá'í Academics Online. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ "Bahá'í Postal Stationery". Bahá'í Philately. Bahá'í Academics Online. 2007-09-17. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ Universal House of Justice (1996). Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1963-1986: the Third Epoch of the Formative Age. compiled by Geoffry W. Marks. Wilmette, Illinois 60091-2844: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. pp. 37–8. ISBN 0-87743-239-2.

- ↑ "Historie". Official Website of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Germany. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Germany. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ The Bahá'í Faith: 1844-1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Bahá'í Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953-1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 84-5.

- 1 2 Momen, Moojan. "Russia". Draft for "A Short Encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith". Bahá'í Library Online. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ↑ "The Baha'i Esperanto League". The Baha'i Faith and Esperanto. Bahaa Esperanto-Ligo. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ See judgement 2BvR 263/86=BVerfGE 83.341 of 05.02.1991 - see Lauden Heising Aktuell

- ↑ Strieth, P and J (1998). "Albania - Family Life Conference". Bahá'í World News Service.

- ↑ Cannuyer, Christian (1998). "Desinformation als Methode. Die Baha'ismus-Monographie des F. Ficicchia". Bahá'í Studies Review. Association for Baha'i Studies (English-Speaking Europe). 08 (1998).

- ↑ Joneleit-Oesch, Silja (University of Heidelberg, Germany) (2001). "The Church and the Gurus". The 2001 International Conference in London. London: Center for Studies on New Religions.

- ↑ Schaefer, Udo (1992). "Challenges to Bahá'í Studies" (PDF). European Conference on Bahá'í activities in Universities (PDF). Brno, Czech.: European Conference on Bahá'í activities in Universities.

- ↑ Ulrich Dehn in Materialdienst der Evangelischen Zentralstelle für Weltanschauungsfragen (EZW), 1/1997, pp. 14-17: “Baha'i und EZW”

- 1 2 Momen, Moojan. "History of the Baha'i Faith in Iran". draft "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith". Bahai-library.com. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ↑ Kingdon, Geeta Gandhi (1997). "Education of women and socio-economic development". Baha'i Studies Review. 7 (1).

- ↑ Momen, Moojan; Smith, Peter (1989). "The Baha'i Faith 1957–1988: A Survey of Contemporary Developments". Religion. 19: 63–91. doi:10.1016/0048-721X(89)90077-8.

- ↑ International Community, Bahá'í (2000-11-05). "500,000 people visit Baha'i exhibit at the Hanover Expo 2000". Bahá'í World News Service.

- ↑ Gottardi, Cosma. "Stimmen Bahás Bahá'í-Chor Deutschland". Bahá'í-Choir Deutschland. Bahá'í-Choir Deutschland. Archived from the original on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ International Community, Bahá'í (2002-06-04). "Faith groups, including Baha'is of Germany, meet on environment and climate concerns". Bahá'í World News Service.

- ↑ Micksch, Jürgen (2009). "Trialog International - Die jährliche Konferenz". Herbert Quandt Stiftung. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ Bahá'í International Community (2009-02-08). "The Frankfurt Regional Conference". Bahá'í World News Service.

- ↑ "Verschiedene Gemeinschaften / neuere religiöse Bewegungen". Religionen in Deutschland: Mitgliederzahlen (Membership of religions in Germany). REMID - the "Religious Studies Media and Information Service" in Germany. 2007–2008. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ Held, Peter. "Biographie". Peter Held - Pianist/Composer. Peter Held. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ "Parisa Badiyi violinist and educator, living in Germany". Arts Dialogue. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ "Brigitte Schirren textiles, Germany.". Arts Dialogue. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ "Hans J. Knospe photopoetry, Germany". Arts Dialogue. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ "Anne Bahrinipour painting, sculpture, Germany". Arts Dialogue. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ Bahá'u'lláh (1873). The Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-85398-999-0.

- ↑ Lambden, Stephen (2000). "Catastrophe, Armageddon and Millennium: some aspects of the Bábí-Bahá'í exegesis of apocalyptic symbolism". Bahá'í Studies Review. 09 (1999/2000).

- ↑ Esslemont, J.E. (1980). Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era (5th ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 244. ISBN 0-87743-160-4.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (1938). The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. pp. 30–1. ISBN 0-87743-231-7.

External links

- Bahá'ís of Germany

- House of Worship in Germany

- Singe die Verse Gottes live recordings at the House of Worship in Germany