Battle of Barrosa

Coordinates: 36°22′19″N 6°10′35″W / 36.3719°N 6.1765°W

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Barrosa (Chiclana, 5 March 1811) was part of an unsuccessful manoeuvre to break the siege of Cádiz in Spain during the Peninsular War. During the battle, a single British division defeated two French divisions and captured a regimental eagle.

Cádiz had been invested by the French in early 1810, leaving it accessible from the sea, but in March of the following year a reduction in the besieging army gave its garrison of British and Spanish troops an opportunity to lift the siege. A large Allied strike force was shipped south from Cádiz to Tarifa, and moved to engage the siege lines from the rear. The French, under the command of Marshal Victor, were aware of the Allied movement and redeployed to prepare a trap. Victor placed one division on the road to Cádiz, blocking the Allied line of march, while his two remaining divisions fell on the single Anglo-Portuguese rearguard division under the command of Sir Thomas Graham.

Following a fierce battle on two fronts, the British succeeded in routing the attacking French forces. A lack of support from the larger Spanish contingent prevented an absolute victory, and the French were able to regroup and reoccupy their siege lines. Graham's tactical victory proved to have little strategic effect on the continuing war, to the extent that Victor was able to claim the battle as a French victory since the siege remained in force until finally being lifted on 24 August 1812.

Background

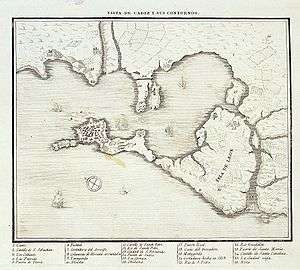

In January 1810, the city of Cádiz, a major Allied harbour and the effective seat of Spanish government since the occupation of Madrid, was besieged by French troops of Marshal Soult's I Corps under the command of Marshal Victor.[1] The city's garrison initially comprised only four battalions of volunteers and recruits, but the Duke of Alburquerque ignored orders from the Spanish Junta and instead of attacking Victor's superior force, he brought his 10,000 men to reinforce the city. This allowed the city's defences to be fully manned.[2]

Under pressure from widespread protests and mob violence the ruling Spanish Junta resigned, and a five-man Regency was established to govern in its place.[lower-alpha 1] The Regency, recognising that Spain could only be saved with Allied aid, immediately asked the newly ennobled Arthur Wellesley, Viscount Wellington, to send reinforcements to Cádiz; by mid-February, five Anglo-Portuguese battalions had landed, bringing the garrison up to 17,000 men and making the city effectively impregnable.[2] Additional troops continued to arrive, and by May, the garrison was 26,000 strong, while the besieging French forces had risen to 25,000.[1]

Although the siege tied up a large number of Spanish, British and Portuguese troops, Wellington accepted this as part of his strategy since a similar number of French troops were also engaged.[3] However, in January 1811, Victor's position began to deteriorate.[4] Soult ordered Victor to send almost a third of his troops to support Soult's assault on Badajoz, reducing the besieging French army to around 15,000 men.[5] Victor had little chance of making progress against the fortress city with a force of this strength, nor could he withdraw—the garrison of Cádiz, if let loose, was large enough to overrun the whole of Andalusia.[4]

Prelude to battle

Following Soult's appropriation of many of Victor's troops, the Allies sensed an opportunity to engage Marshal Victor in open battle and raise the siege of Cádiz.[6] To that end, an Anglo-Spanish expedition was sent by sea from Cádiz south to Tarifa, with the intention of marching north to engage the French rear. This force comprised some 8,000 Spanish and 4,000 British troops, with the overall command ceded to the Spanish General Manuel la Peña, a political accommodation since he was widely regarded as incompetent.[7] To coincide with la Peña's assault, it was arranged that General José Pascual de Zayas y Chacón would lead a force of 4,000 Spanish troops in a sally from Cádiz, via a pontoon bridge from the Isla de León.[8]

The Anglo-Portuguese contingent — a division commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Graham — sailed from Cádiz on 21 February 1811, somewhat later than planned.[9] Graham's forces were unable to land at Tarifa due to bad weather and were forced to sail on to Algeciras, where they disembarked on 23 February.[10] Joined by a composite battalion of flank companies under Colonel Browne, the troops marched to Tarifa on 24 February, where they received a further reinforcement from the fortress garrison there.[11] By 27 February, they were joined by la Peña's Spanish troops, who had left Cádiz three days after Graham and, despite encountering similar weather difficulties, had succeeded in landing at Tarifa.[9]

To further strengthen the Allied ranks, a force of Spanish irregulars under General Antonio Begines de los Ríos had been ordered to come down from the Ronda mountains by 23 February and join the main Anglo-Portuguese and Spanish force. Unaware of the delays in sailing, Begines had advanced as far as Medina-Sidonia in search of the Allied army; unsupported, and embroiled in skirmishes with Victor's right flank, he returned to the mountains. General Cassagne, Victor's flank commander, informed the Marshal of the developing threat. Victor responded by sending three infantry battalions and a cavalry regiment to reinforce Cassagne, and ordering the fortification of Medina-Sidonia.[12]

Having concentrated, the combined Allied force began marching north towards Medina-Sidonia on 28 February, and la Peña now ordered Beguines's irregulars to join them at Casas Viejas. Once there, however, Beguines's scouts reported that Medina-Sidonia was held more strongly than had been anticipated. Rather than engaging the French and forcing Victor to weaken his siege by committing more of his troops to the town's defence, la Peña decided that the Allied army should march across country and join the road that ran from Tarifa, through Vejer and Chiclana, to Cádiz.[13]

This change of plan, combined with further bad weather and la Peña's insistence on marching only at night, meant the Allied force was now two days behind schedule.[10] La Peña sent a message to Cádiz informing Zayas of the delay, but the dispatch was not received and on 3 March, Zayas launched his sally as arranged.[lower-alpha 2] A pontoon bridge was floated across the Santi Petri creek and a battalion sent across to establish a bridgehead prior to the arrival of the main force. Victor could not allow the Cádiz garrison, which still numbered about 13,000 men, to make a sortie against his lines while he was threatened from outside, so on the night of 3–4 March he sent six companies of voltigeurs to storm the bridgehead entrenchments and prevent a breakout. Zayas's battalion was ejected from its positions, with 300 Spanish casualties, and Zayas was forced to float the pontoon bridge back to the island for future use.[lower-alpha 3]

Marshal Victor had, by now, received intelligence from a squadron of dragoons that had been driven out of Vejer, informing him of the strong Anglo-Portuguese and Spanish force making its way up the western road from Tarifa. In conjunction with the aggressive action of the Cádiz garrison, this led him to conclude that the approaching troops were heading for Cádiz; their line of march was therefore predictable, so he prepared a trap.[14] General Eugène-Casimir Villatte's division was sent to block the neck of the peninsula on which the western road ran, preventing access to the Santi Petri creek and the Isla de Léon. Two other divisions, under the commands of Generals François Amable Ruffin and Jean François Leval, were ordered to conceal themselves in the thick Chiclana forest in position to attack the flank of the Allies as they engaged Villatte's division.[15]

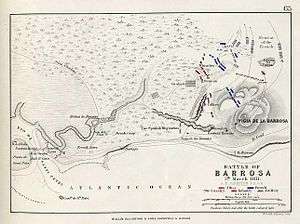

After another night march, on 5 March the Allies reached a hill to the south east of Barrosa, the Cerro del Puerco (also referred to as the Barrosa Ridge). Scouts reported the presence of Villatte's force, and la Peña ordered his vanguard division to advance. With the aid of a fresh sortie of Zayas's troops from Cádiz, and reinforced by a brigade of the Prince of Anglona's division, the Spanish drove Villatte's force across the Almanza Creek.[16] La Peña refused his vanguard permission to pursue the retreating French, who were consequently able to regroup on the far side of the creek. Graham's Anglo-Portuguese division had remained behind on the Cerro del Puerco to defend the rear and right flank of la Peña's main force.[17]

Battle

Having opened up the route to Cádiz, la Peña instructed Graham to move his troops forward to Bermeja.[16] However, on Graham's strenuous objections to vacating a position that would result in both an exposed flank and rear, a force of five Spanish battalions and Browne's battalion was left to hold the Barrosa Ridge. In addition, three Spanish and two King's German Legion (KGL) squadrons of cavalry, under the command of Colonel Samuel Whittingham, were sent to flank this rearguard force on the coast track.[lower-alpha 4] Graham's division then moved north as ordered—instead of descending from the heights on the coast road, they followed a path through a pine wood to the west of the ridge. This route was shorter and more practical for artillery, but the trees restricted visibility in all directions, meaning that they were effectively marching blind.[18]

French attack

Victor was disappointed that Villatte had failed to block the Cádiz road for longer, but he was still confident that his main force could drive the Allies into the sea.[19] He could see that the bulk of the Spanish troops had taken station opposite Villatte and, on hearing reports that Barrosa Ridge was deserted, realised that here was an opportunity to take this commanding position. Ruffin was ordered to occupy the heights while Leval struck at Graham's troops in the woods, and three squadrons of dragoons were sent around the Cerro to take the coastal track.[20]

Victor's plan rapidly developed momentum. Ruffin's advance sufficed to send the five rearguard Spanish battalions running, leaving only Browne's battalion defending the ridge and, confronted by the French dragoons, Whittingham's cavalry decided to retire.[lower-alpha 5] Whittingham lent a single squadron of KGL hussars to Browne to cover his retreat; Browne initially positioned his battalion in the ruins of a chapel at the summit but, seeing Whittingham's retreat and spotting six French battalions advancing on his position, he had little choice but to give way and seek Graham's force in the woods. Barrosa Ridge fell unopposed as Victor had intended, and Ruffin emplaced a battery of artillery on the heights.[20]

Graham's response

Meanwhile, midway through his march to join la Peña's Spaniards, Graham received news from Spanish guerrilleros that French soldiers had emerged from the Chiclana forest.[21] Riding to the rear of his marching columns, he witnessed the Spanish battalions retreating from the ridge, Ruffin's division climbing its slopes, and Leval's division approaching from the east. Realizing that the Allied force was in danger of being swamped, Graham disregarded his orders and turned his division to deal with the threats to his flank and rear. He ordered General Dilkes's brigade to retake the ridge while Colonel Wheatley's brigade was sent to see off Leval's force to the east.[22]

Because of the time it took to deploy a full brigade into battle formation, Graham knew he needed to delay the French. He therefore ordered Browne, who had rejoined the division, to turn his single "Flankers" battalion of 536 men around and advance up the slope of the Barrosa Ridge against the 4,000 men and artillery of Ruffin's division. Colonel Barnard, who led the light battalion of Wheatley's brigade, and Colonel Bushe, leading two light companies of Portuguese skirmishers, were ordered to attack through the woods to hold up Leval's advance.[19]

Barrosa Ridge

Advancing up the ridge they had just abandoned, Browne's battalion came under intense fire from Ruffin's emplaced infantry and artillery. Within a few salvoes, half the battalion was gone and, unable to continue, Browne's men scattered amongst the cover provided by the slope and returned fire.[23] Despite his success, Ruffin could not descend the hill to brush away the remnants of Browne's battalion, as Dilkes's brigade had by now emerged from the wood and was forming up at the base of the slope.[24]

Dilkes, instead of following Browne's route up the slope, advanced to the right where there was more cover and ground not visible to the French. As a result, the French artillery could not be brought to bear, and Dilkes's brigade managed to get near the top of the ridge without suffering serious loss. By this time, though, its formation had become disorganised, so Ruffin deployed four battalion columns in an attempt to sweep both Dilkes and the remaining "Flankers" back down the slope. Contrary to French expectations, the crude British line stopped the attacking columns in their tracks, and the two forces exchanged fire.[lower-alpha 6] Marshal Victor, by then himself on the crest of the ridge, brought up his reserve in two battalion columns of grenadiers. These columns were, as with the previous four, subjected to intense musket fire and were brought to a halt just metres from the British line. The first four columns had started to give ground, so Victor tried to disengage his reserves and bring them to their support. However, as the two grenadier columns attempted to move off from their stalled positions, they came under additional fire from the remnants of Browne's battalion, which had renewed its own advance. Prevented from rallying, the entire French force broke and fled to the valley below.[24]

Leval's advance

While Dilkes was moving on Ruffin's position on Barrosa Ridge, Barnard and the light companies advanced through the woods towards Leval's division. Unaware of the impending British assault, the French had taken no precautions and were advancing in two columns of march, with no forward line of voltigeurs. The unexpected appearance of British skirmishers caused such confusion that some French regiments, thinking there were cavalry present, formed square. These were prime targets for shrapnel rounds fired by the ten cannon under Major Duncan which, having made rapid progress through the woods, arrived in time to support the skirmish line.[25] As the situation became clearer, the French organised themselves into their customary attacking formation—the 'column of divisions'—all the time under fire from Barnard's light companies and Duncan's artillery. Finally, with the French now in their fighting columns and beginning their advance, Barnard was forced to draw back. Leval's men then encountered Bushe's companies of the 20th Portuguese, who supported the light battalion's retreat and kept the French engaged until Wheatley's brigade had formed up in line on the edge of the woods. The retreating light companies joined Wheatley's troops; Leval's division of 3,800 men was now marching on an Anglo-Portuguese line of 1,400 men supported by cannon.[26]

Although they had the advantage in numbers, the French were under the impression that they were facing a superior force.[lower-alpha 7] Having been mauled by Barnard's and Bushe's light companies, and now facing the rolling volleys of the main British line, the French needed time to form from column into line themselves. However, Wheatley attacked as soon as the light companies cleared the field, and only one of Leval's battalions was able to even partially redeploy. The first French column Wheatley engaged broke after a single British volley.[27] The 8th Ligne, part of this column, suffered about 50 percent casualties and lost its eagle. The capture of the eagle—the first to be won in battle by British forces in the Peninsular wars—cost Ensign Keogh of the 87th his life and was finally secured by Sergeant Patrick Masterson (or Masterman, depending on source).[lower-alpha 8] As Wheatley's brigade moved forward, it encountered the only French battalion, from the 54th Ligne, that had begun to form line. It took three charges to break this battalion, which eventually fled towards the right where it encountered the remainder of Leval's fleeing division.[28]

French retreat

Ruffin's and Leval's divisions fled towards the Laguna del Puerco, where Victor succeeded in halting their disorganised rout. The Marshal deployed two or three relatively unscathed battalions to cover the reorganisation of his forces and secure their retreat, but Graham had also managed to call his exhausted men to order and he brought them, with Duncan's artillery, against Victor's new position. Morale in the re-formed French ranks was fragile; when a squadron of KGL hussars rounded the Cerro and drove a squadron of French dragoons onto their infantry,[lower-alpha 9] the shock was too much to bear for the demoralised soldiers, who retreated in a sudden rush.[29]

Throughout the battle, la Peña steadfastly refused to support his Anglo-Portuguese allies. He learnt of the French advance at about the same time as Graham, and decided to entrench his full force on the isthmus defending the approach to the Isla de Léon. Learning of Graham's decision to engage the two French divisions, the Spanish commander was convinced that the French would win the day and so stayed in place;[30] Zayas repeatedly asked for leave to go to Graham's support, but le Peña denied permission each time. On hearing that the British had prevailed, la Peña further declined to pursue the retreating French, again over-riding the continued protestations of Zayas.[31]

Consequences

Furious at la Peña, the following morning Graham collected his wounded, gathered trophies from the field and marched into Cádiz; snubbed, la Peña would later accuse Graham of losing the campaign for the Allies.[lower-alpha 10] It is almost certain that, had the Allies pushed the French positions either immediately after the battle or on the morning of 6 March, the siege would have been broken. Even though Victor had managed to rally his troops at Chiclana, panic was rife in the French lines. Fully expecting a renewed offensive, Victor had made plans to stall any Allied advance just long enough to blow up most of the besieging forts and to allow I Corps to retreat to Seville.[32] Such was the French discomposure that, despite the Allied inactivity, one battery was destroyed without any signal being given.[33]

La Peña had determined not to heed plans from Graham and Admiral Keats to make a cautious advance against the French at Chiclana, and he even refused to send out cavalry scouts to find out what Victor was doing. After remaining entrenched at Bermeja during 5–6 March, the Spanish army crossed to the Isla de León the following day, leaving only Beguines's irregulars on the mainland. This force did manage to briefly secure Medina-Sidonia, but then returned to the Ronda mountains. By 8 March, just three days after the battle, Victor had reoccupied even the evacuated southern section of his lines and the siege was back in place.[33] It would remain so for another eighteen months, until finally being abandoned on 24 August 1812, when Soult ordered a general French retreat following the Allied victory at Salamanca.[lower-alpha 11]

Despite the conduct of their commanding general,[lower-alpha 12] both the Spanish success at Almanza Creek and Graham's actions at Barrosa Ridge gave a much needed boost to Spanish morale.[34] La Peña was subsequently arraigned for court-martial, mainly for his refusal to pursue the retreating French, where he was acquitted but relieved of command.[35] At a time when Anglo-Spanish relations were already strained, Graham's criticism of his Spanish allies meant that it was no longer politic for him to remain in Cádiz, so he was transferred to Wellington's main army.[36]

Both tactically and in terms of the casualties inflicted, the battle was a British victory. Graham's troops had beaten a French force approaching twice their number despite having marched through the previous night and part of that day. The British lost approximately 1,240 men, including Portuguese and German contingents under Graham's command, while Victor lost around 2,380. The Spanish suffered 300–400 casualties.[lower-alpha 13] Strategically, however, the failure of the Allies to follow up their victory allowed Victor to reoccupy his siege lines; Cádiz was not relieved and the campaign effectively failed to achieve anything. Victor even claimed the battle as a French victory, since the positions of the opposing sides remained unchanged following the action.[37]

Legacy

In November 1811, the British Prince Regent commanded that a medal be struck to commemorate the "brilliant Victory obtained over the Enemy"; this was awarded to the senior British officers present at the battle.[38]

Four Royal Navy ships have taken their names from the battle, as has the Sea Cadet Corps Unit, TS Barrosa.

A young officer in the 4th Dragoons, Lieutenant William Light who later served on Graham's staff and was a great admirer of the general, subsequently became the Surveyor General of South Australia in the 1830s. Light decided to name one of the valleys in the new colony Barossa Valley (now a famous wine making region) in memory of the victory, albeit misspelled due to a clerical error. It is often incorrectly stated that Light fought at the Battle of Barrosa but he was actually hundreds of miles to the north, his diary of 6 March 1811 recording he was with Wellington's cavalry travelling through Santarem to Pernes.

Unofficially, the training area at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst is also known as Barossa.

In fiction

- Cornwell, Bernard, Sharpe's Fury: Richard Sharpe and the Battle of Barrosa, March 1811, HarperCollins, 2006, ISBN 978-0-06-053048-8.

References

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Esdaile 2002, p. 284. Note that the number of members (five) contradicts Glover (1974, p. 119), which states three members. Esdaile (2002, p. 307) explains that the first five-man Regency resigned and was replaced by a group of three.

- ↑ Ironically, the messenger, a Spanish officer sent in a fishing boat, was detained by a Royal Navy brig as a 'suspicious character' (Oman 1911, p. 104, footnote).

- ↑ Oman 1911, pp. 103–104. Paget (1990, p. 122) claims that the bridgehead was actually held, but Gates (1986, p. 249) agrees that this sortie was repelled.

- ↑ Whittingham was an English officer serving with the Spanish army, and hence under la Peña's command (Jackson 2001, para. 2).

- ↑ Browne was reported to have said "Because five Spanish battalions went off before the enemy came within cannon shot" when asked by Graham to explain why Browne's company had retreated from the ridge. From the memoirs of Browne's adjutant, Blakeney (Glover 1974, p. 124).

- ↑ Ruffin later spoke of "the incredibility of such a rash attack" (Paget 1990, p. 124).

- ↑ Most of the French memoirs say that they had been attacked by three British lines, when there was only one, preceded by a screen of skirmishers (Oman 1911, pp. 119–120).

- ↑ Muzás (2005, para. 1) gives details of the taking of the eagle, while Glover (1974, p. 125) is an example of the use of 'Masterman' rather than the more common 'Masterson'.

- ↑ These hussars were from Whittingham's squadrons, but were acting on the orders of Graham's aide-de-camp Ponsonby (Oman 1911, p. 123).

- ↑ Oman 1911, p. 129. Wellington, however, sent his approval to Graham, writing "I concur in the propriety of your withdrawing to the Isla on the 6th, as much as I admire the promptitude and determination of your attack on the 5th" (Oman 1911, p. 125).

- ↑ Weller 1962, p. 234; Glover (1974, p. 210) agrees with this date, but Esdaile (2002, p. 400) states 25 August.

- ↑ Fortescue (1917, p. 62) writes "It was nothing to him if the opportunity for a great victory were missed. That was of small account compared to the integrity of his person and reputation.", while Oman (1911, p. 124) describes le Peña's conduct as "astounding", "selfish" and "timid".

- ↑ Haythornthwaite (2004, p. 225) provides the casualty figures, with the British numbers taken from the London Gazette, 25 March 1811.

Citations

- 1 2 Gates 1986, p. 242.

- 1 2 Glover 1974, p. 119.

- ↑ Paget 1990, p. 36.

- 1 2 Gates 1986, p. 249.

- ↑ Jackson 2001, para. 1.

- ↑ Esdaile 2002, p. 335.

- ↑ Jackson 2001, para. 2.

- ↑ Paget 1990, pp. 121–122.

- 1 2 Oman 1911, p. 98.

- 1 2 Paget 1990, p. 122.

- ↑ Fortescue 1917, p. 41.

- ↑ Oman 1911, p. 98, footnote.

- ↑ Oman 1911, pp. 99–102.

- ↑ Fortescue 1917, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Oman 1911, pp. 103–107.

- 1 2 Fletcher 1999, para. 8.

- ↑ Oman 1911, p. 107.

- ↑ Oman 1911, pp. 107–108.

- 1 2 Gates 1986, p. 251.

- 1 2 Oman 1911, pp. 108–110.

- ↑ Jackson 2001, para. 5.

- ↑ Paget 1990, p. 123.

- ↑ Fortescue 1917, pp. 53–54.

- 1 2 Oman 1911, pp. 113–117.

- ↑ Fortescue 1917, p. 46.

- ↑ Oman 1911, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Fortescue 1917, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Oman 1911, pp. 119–122.

- ↑ Oman 1911, p. 123.

- ↑ Fortescue 1917, p. 62.

- ↑ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ Fortescue 1917, p. 66.

- 1 2 Oman 1911, pp. 125–128.

- ↑ Parkinson 1973, p. 128.

- ↑ Paget 1990, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 99.

- ↑ Oman 1911, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Torrens 1811, para. 2.

Bibliography

- Esdaile, Charles (2002), The Peninsular War, Penguin Books (published 2003), ISBN 0-14-027370-0;

- Fletcher, Ian (1999), Barrosa, UK: IFBT, archived from the original on 2007-08-14, retrieved 2007-09-03;

- Fortescue, John (1917), A History of the British Army, VIII, Macmillan, retrieved 2007-09-13;

- Gates, David (1986), The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War, Pimlico (published 2002), ISBN 978-0-7126-9730-9;

- Glover, Michael (1974), The Peninsular War 1807–1814: A Concise Military History, Penguin Classic Military History (published 2001), ISBN 978-0-14-139041-3;

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (2004), Brassey's Almanac: The Peninsular War; The Complete Companion to the Iberian Campaigns, 1807–14, Chrysalis Books, ISBN 978-1-85753-329-3;

- Jackson, Andrew (2001), The Battle of Barrosa, 5th March 1811, Peninsular war, retrieved 2007-09-03;

- Muzás, Luis (2005), Trophies Taken by the British from the Napoleonic Army during the War of Spanish Independence (Peninsular War) 1808–1814, The Napoleon Series, retrieved 2007-09-08;

- Oman, Sir Charles (1911), A History of the Peninsular War: Volume IV, December 1810 to December 1811, Greenhill Books (published 2004), ISBN 978-1-85367-618-5;

- Paget, Julian (1990), Wellington's Peninsular War; Battles And Battlefields, Pen & Sword Military (published 2005), ISBN 978-1-84415-290-2;

- Parkinson, Roger (1973), The Peninsular War, Wordsworth Editions (published 2000), ISBN 978-1-84022-228-9;

- Torrens, H (9 November 1811), "Horse-Guards Memorandum", London Gazette (16539), p. 2, retrieved 2009-04-21;

- Weller, Jac (1962), Wellington in the Peninsula, Nicholas Vane.