Battle of Kunersdorf

| Battle of Kunersdorf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Seven Years' War | |||||||

Painting by Alexander Kotzebue, 1848 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

50,900 Soldiers 230 guns |

65,000: 41,000 Russian soldiers, including 5,200 Cossack and Kalmyk Cavalry 24,000 Austrian soldiers[1] 250 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

25,623 (540 officers, 25,083 soldiers): 6,271 killed 11,342 wounded 1,356 missing 4,599 captured 2,055 deserted 172 guns (164 Russian guns that Prussians captured at the beginning of the campaign and 8 Prussian guns) 27 banners 2 standards |

23,512 (7,060 killed, 1,150 missing, 15,302 wounded); 5,000 were also captured at the battle start: Russian: 19,181 (18,615 soldiers and 566 officers) 5,614 killed 12,864 wounded 703 missing Austrian: 4,331 (4,115 soldiers and 216 officers): 1,446 killed 2,438 wounded 447 missing | ||||||

The Battle of Kunersdorf, fought in the Seven Years' War, was Frederick the Great's most devastating defeat. On August 12, 1759, near Kunersdorf (Kunowice), east of Frankfurt (Oder), 50,900 Prussians were defeated by a combined allied army 65,000 strong consisting of 41,000 Russians and 24,000 Austrians under Pyotr Saltykov and Ernst Gideon von Laudon. Only 3,000 soldiers from the original 50,900 comprising the Prussian army returned to Berlin after the battle, though many more had only scattered and were ultimately able to join the army afterward.

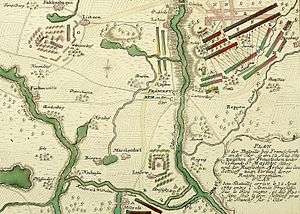

Situation in 7-Years-War

By 1759, Prussia had reached a strategic defensive position in the war; Russian and Austrian troops surrounded Prussia, although not quite on the borders. Upon leaving winter quarters in April 1759, Frederick assembled his army in Lower Silesia; this forced the main Habsburg army to remain in its staging army in Bohemia. The Russians, however, shifted their forces into western Poland, a move that threatened the Prussian heartland, Brandenburg, and potentially Berlin itself. Frederick countered by sending an army corps, commanded by Friedrich August von Finck, to contain the Russians. Finck's efforts were defeated at the Battle of Kay, July 23. Subsequently, the Russian forces, commanded by Pyotr Saltykov, subsequently occupied Frankfurt an der Oder, Prussia's second largest city, on 31 July, and began entrenchment of their camp near Kunersdorf. To make matters worse for the Prussians, an Imperial corps of 19,200 soldiers, commanded by Ernst Gideon von Laudon, joined them on August 5. King Frederick rushed from Saxony, took over the remaining contingent of Lieutenant General Carl Heinrich von Wedel at Müllrose and moved across the Oder River. By the time he reached Kunersdorf, his forces had been enhanced by Finck's defeated corps, and another corps moving the the Lausitz region: by 9 August, he had 49,000 troops.[2]

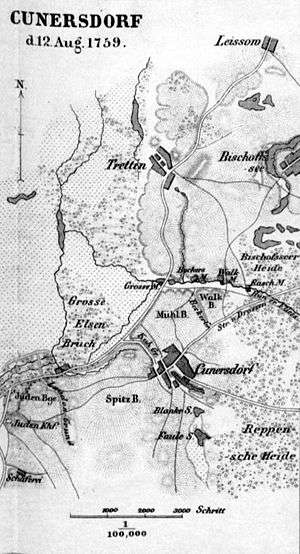

Dispositions

Saltykov crossed the Oder on the same day as Frederick, and knew of Frederick's movements. Instead, he established his troops on a strong position from with to receive the Prussian attack. He and the Austrian troops were stretched along a ridge of small hills that ran north-easterly from the outskirts of Frankfurt to just north of the village of Kunersdorf (Kunovice). A stream flowed in a depression beyond these hills, called the Hühner-Fliess, northwesterly toward the Oder. Two other depressions intersected the ridge, creating three distinct promontories. The western portion was a 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) stretch from the Juden-Berge in the south-west to the highest ground in the area, the Grosser Spitzberg and its outcropping int he north east. A narrow depression, known as the Kuhgrund, lay beyond that. After the Kuhgrund, the ground rose again into another hill, called Mühl-Berge. Beyond this lay a second depression known as Baecker-grund, then a slight rise known as the Walk-Berge. There was additional high ground to the east of Kunersdorf, called the Kleiner Spitzberg. Saltykov entrenched himself in a position running from the Juden-Berge through the Grosser-Spitzberg to the Mühl-Berge, and faced his troops to the south east. He had little concern about the northwestern face of the ridge, which was steep and fronted by a swampy ground called the Elsbruch, but a few of the Austrian contingents to his right faced northwester as a precaution.[3] He knew that the Frederick had crossed the Oder south of Frankfurt and would attack from the south-east.[4]

The Prussians reached the area north of the Hühner-Fliess on 11 August. Frederick made a perfunctory reconnaissance of his enemy's position, but did not send scouts to reconnoiter the land or question locals about the ground; instead, he decided that all the Allies were facing northwest. He placed a diversionary force, commanded by Finck, at the Hühner Fliess, which would apparently threaten the north-eastern portion of the Allied position, and marched his main army around to the south east This way, he thought he would surprise his enemy. This would force his enemy to reverse fronts, a fairly complicated maneuver, and Frederick could employ his much feared oblique battle order, feigning with his left flank as he did so. Ideally, this would allow him to roll up the Allied line from the Muhl-Berge.[4]

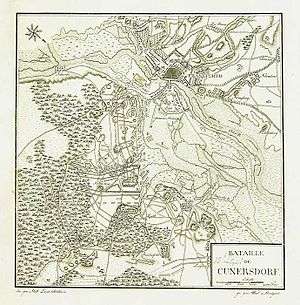

Battle

It started with a Prussian attack on the flank of the Russian positions on the morning of 12 August. Early i the battle Frederick realized tat he was actually facing his enemy, instead of coming up behind them. Furthermore, a row of ponds forced him to break his line, exposing it to greater fire power, and diminishing its impact. He changed his dispositions; the Prussians would concentrate east of the ponds of Kunersdorf, and make an assault on the Mühl-Berge. Frederick calculated that he could turn the Austrian-Russian flank. His re-deployment took some time, and the hesitation in the assault confirmed to Saltykov what Frederick was planning.[4]

As the Prussians approached, their own artillery batteries created an arc of artillery fire on the sector by Walk-Berge and the Kleiner Spitzberg. Shuvalov's Observation Corps stationed on the Mühl-Berge took substantial losses--perhaps 10%--and Saltykov sent grenadiers to shore them up, but the Prussians carried the Mühl-Berge, but despite their success there, the position was not substantially better than a few hours earlier. To take the full Austro-Russian force, the Prussians would have to descend to the lower Kuhgrund and then assault a well-defended higher ground.[4]

Prince Henry and several of the Prussian generals encouraged Frederic to stop there. The Prussians held the high ground between the Austro-Russian force and Frankfurt. Frederick's generals asked him to stop. To descend into the valley and ascend against frightful fire was foolhardy, they argued. Furthermore, the weather was blistering hot, the troops had endured forced marches to reach the battle field. However, Frederick wanted to press his initial success and decided to continue the fight. [5] He transferred his artillery to the Mühl-Berge, and ordered Finck's battalions to assault the Allied salient from the north-west, while his main strike would cross the Kuh-grund ravine.[4]

Saltykov was ready for him and had reinforced the salient with reserves from the west and south-west; these reserves most of Loudon's infantry. Finck made no progress at the salient and the Prussia attacks at the Kuh-grund were thwarted with murderous fire along a very narrow front. Despite the fierce fighting, it looked lie the Prussians might break through,but gradually the Allied superiority (423 artillery pieces) could be brought to bear on the Prussians as they struggled up the hill, and the Allied grenadiers held their lines. Saltykov fed in reinforcements judiciously from other sectors.[5]

Cavalry attack

The battle culminated in the early evening hours with a massive Prussian cavalry charge under Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz upon the Russian center and artillery positions. The Prussian cavalry suffered heavy losses from cannon fire and retreated in complete disorder. Seydlitz himself was badly wounded and, in his absence, Lieutenant General Dubislav Friedrich von Platen assumed command. He organized the last-ditch effort. His scouts had discovered a suitable crossing past the chain of ponds south of Kunersdorf, but would have to deal with the artillery batteries on the Grosser Spitzberg. Seydlitz, wounded and but still following the action, noted that it was foolish to charge a fortified position with cavalry. The units sent against the position shattered; before any further action could take place, Loudon himself led a Austrian and Russian horse counter-attack and routed Platen's cavalry. The fleeing men and horses trampled their own infantry around the Mühl-Berge and general panic ensued.[5]

At this point the battle was lost. The Prussians lost almost 20,000 men and almost all their artillery. Frederick, who was in the very middle of the action but unhurt, barely escaped capture. Two of his horses were shot out from under him, his uniform was torn, and a snuff-box in his pocket was pulverized. He stood alone on a small hill with his rapier sticking in the ground before him—determined to either hold the line against the whole enemy army alone or die. Hussar Captain Ernst Sylvius von Prittwitz came to the king's rescue with his 200-strong squadron and convinced Frederick to leave. Major Ewald Christian von Kleist was severely injured and succumbed to his wounds twelve days later.[6]

Aftermath

The Russians and Austrians lost fewer than 15,000 men (approx. 5,000 killed), although a few sources suggest ha slightly higher number, perhaps 15,600. Regardless the percentage of Russian and Austrian losses were at about 26 percent. The Prussians suffered a severe defeat losing 172 cannons, 6,000 killed, 13,000 wounded, more than 37 percent,[7] and 26,000 men were scattered over the territory between Kunersdorf and Berlin; by the end of the battle itself, Frederick though he had 5,000 men capable of mounting any kind of organized resistance. Four days after the battle however, most of the 26,000 scattered men turned up at the headquarters on the Oder River and Frederick's army recovered to a strength of 32,000 men and 50 cannon. The crushing defeat remained without consequences as the victors omitted the opportunity to march against Berlin and retired to Saxony instead. Frederick wrote of the "Miracle of the House of Brandenburg" in a letter to his brother Henry on 1 September. Russian army would no longer fight any major battle, allowing the Prussians to focus on the Austrians.

The Battle of Kunersdorf was the first battle in which regular units of horse artillery were deployed. These were a hybrid of cavalry and artillery in which the entire crews rode horses into battle, on of Frederick's notable inventions. Despite being wiped out during the battle, he reorganized these mobile batteries later in the year and they participated in the Battle of Maxen.[8]

Assessment

Most military historians will agree that Kunersdorf was Friedrich's greatest, and most catastrophic, loss. They attribute it variously to his indifference to the Russian practices of the "art of war", to his lack of information about the ground, and his inability to realize that the Russians had, effectively, surmounted the obstacles of location. Frederick had made limited efforts to assess the terrain: the Russians and the Austrians had discovered a causeway between the lakes and the marshland that allowed them to present Frederick with a united front. This ability effectively cancelled any advantage Frederick could muster with the use of the oblique battle order. Furthermore, the Russians utilized a naturally defensible position that forced the Prussians to employ clumsy tactics. Despite the murderous fire, though, Frederick's troops eventually turned the Russian left, but to little benefit since the terrain allowed the Russians and Austrians to form a compact front shielded by the hills and marshes.[9]

Perhaps Frederick most egregious mistake was his refusal to consider the recommendations of his trusted staff. His brother's reasonably suggested the halt the battle at mid-day on the 12th, after the Prussians had secured the first height. From this vantage point, they would be unassailable, and eventually, the Austro-Russian force would have to withdraw.[4] Instead of holding his secure position, Frederick forced his troops to descend the hill, cross the low ground, and ascend the next hill in the face of heavy fire. The subsequent Prussian cavalry effort was badly coordinated and, despite an initial success that drove back the Russian and Austrian squadrons, the fierce fire from the united Allied front eventually inflicted staggering losses on Frederick's much-vaunted cavalry. Furthermore, he committed perhaps the gravest of errors in sending his cavalry into battle piece meal, and against entrenched positions.[9]

Sources differ on the losses: Frederick lost between 19,000 and 25,000 killed wounded and captured and the Russians lost about 15,000. Saltykov and Loudon left the field with intact armies, and with extant communications between one another. Frederick was not so fortunate: he had approximately less than 5,000 men capable of offering any sort of resistance.[9]

The king wrote to Berlin to Karl Wilhelm von Finckensten, on the evening after the battle:

This morning at 11 o'clock I have attacked the enemy. ... All my troops have worked wonders, but at a cost of innumerable losses. Our men got into confusion. I assembled them three times. In the end I was in danger of getting captured and had to retreat. My coat is perforated by bullets, two horses of mine have been shot dead. My misfortune is that I am still living ... Our defeat is very considerable: To me remains 3,000 men from an army of 48,000 men. At the moment in which I report all this, everyone is on the run; I am no more master of my troops. Thinking of the safety of anybody in Berlin is a good activity ... It is a cruel failure that I will not survive. The consequences of the battle will be worse than the battle itself. I do not have any more resources, and - frankly confessed - I believe that everything is lost. I will not survive the doom of my fatherland. Farewell forever!

Frederick complicated his own fate by violating every principle of war he had espoused in his own writing, particularly the one on reconnaissance. On the basis of meager information and almost no understanding of the ground, he had thrown his infantry into the teeth of gun fire; he compounded this folly by committing his cavalry piecemeal to pointless charges. Although he had matured considerably since the disaster at Mollwitz in 1741, he still acted on ground of his enemy' choosing, not his own. Langer and Pois suggest, though, that he violated all his own rules because he was facing an enemy he despised, and this brought out the worst of his generalship.[10]

Notes

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Autriche, Jean-Paul Bled

- ↑ David T. Zabecki, Germany at War: 400 years of Military History. ABC-CLIO, 2014.

- ↑ Franz Szabo, The Seven Years War in Europe: 1756-1763. Routledge, 2013. p. 236.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Szabo, p. 237.

- 1 2 3 Szabo, p. 238.

- ↑ Nancy Mitford, Frederick the Great, p. 232.

- ↑ Paul Wanke, Russian/Soviet Military Psychiatry 1904ndash;1945. Psychology Press, 2005, p. 5.

- ↑ Hedberg pp. 11-13

- 1 2 3 Philip Langer, Robert Pois, Command Failure in War: Psychology and Leadership. Indiana University Press, 2004, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Langer and Pois, p. 22-24.

Sources

- Hedburg, Jonas (ed), Kungliga artilleriet: Det ridande artilleriet (1987) (summary in English) ISBN 91-85266-39-6

- Langer, Philip, Robert Pois, Command Failure in War: Psychology and Leadership. Indiana University Press, 2004

- Mitford, Nancy. Frederick the Great. New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

- Poulos, Battle of Kunersdorf in "Extreme War: The Military Book Club's Encyclopedia of the Biggest, Fastest Bloodiest, & Best in Warfare" Citadel Press, 2007.

- Szabo, Franz, The Seven Years War in Europe: 1756-1763. Routledge, 2013.

- Wanke, Paul, Russian/Soviet Military Psychiatry 1904-1945. Psychology Press, 2005.

Coordinates: 52°21′11″N 14°36′46″E / 52.35306°N 14.61278°E