Battle of Nagysalló

| Battle of Nagysalló | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total: 23,784 men - I. corps: 9465 - III. corps: 9419 - VII. corps: 4900 87 cannons[1] |

Total: 20,601+? men[2] 55 cannons[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Total: 608 men |

Total: 1538 men - 112 dead - 189 wounded - 1237 missing and captured[4] | ||||||

The Battle of Nagysalló was fought on 19 April 1849, was one of the battles of the Spring Campaign in the Hungarian War of Independence from 1848–1849, fought between the Habsburg Empire and the Hungarian Revolutionary Army. Until 1918 Nagysalló was a part of the Hungarian Kingdom, today being a village in Slovakia, its Slovakian name being Tekovské Lužany. This was the 2. battle in the second phase of the Spring Campaign, which had the purpose to relieve the fortress of Komárom from the imperial siege, and with this to encircle the Habsburg imperial forces headquartered in the Hungarian capitals of Buda and Pest. The Hungarians won the battle in a categorical way against the imperial troops led by Lieutenant General Ludwig von Wohlgemuth, which came from the Habsburg Hereditary Lands (Vienna, Styria, Bohemia, Moravia), to help the imperial army sent to suppress the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and independence.

Background

After the Battle of Vác the Hungarian army continued its advancement, according to the plan of the second phase of the Spring Campaign developed in 7 April.[5] According to this plan the Hungarian army had to split, General Lajos Aulich with the II. Hungarian Army Corps, and the division of Colonel Lajos Asbóth remained infront of Pest, doing such military maneuvers which have to make the imperials to believe that the whole Hungarian army is there, diverting their attention from north, where the real Hungarian attack had to start with the I., III. and the VII., corps which had to go westwards, on the northern bank of the Danube via Komárom, to relieve it from the imperial siege.[6] The Kmety division of the VII. corps had to cover the three corps march, and after the I. and the III. corps occupied Vác, the division had to secure the town, while the rest of the troops together with the two remaining divisions of the VII. corps, had to advance to Garam river, than heading for the south to relieve the northern section of Austrian siege of the fortress of Komárom.[7] After this, they had to cross the Danube and relieve the southern section of the siege.[8] In the eventuality of finishing all of these with success, the imperials had only two chances: Or to retreat from Middle Hungary towards Viena, or face the encirclement from the Hungarian troops in Pest and Buda.[9] This plan was very risky (as was the first plan of the Spring Campaign too) because if Windisch-Grätz would had discovered that in front of Pest remained only a Hungarian corps, with an attack could destroy Aulich's troops, and with this he could easily cut the support lines of the main Hungarian army, and even occupy Debrecen, the seat of the Hungarian Revolutionary Parliament and the National Defense Committee (interim government of Hungary), or he could encircle the three corps advancing to relieve Komárom.[10]

Although the president of the National Defense Committee (interim government of Hungary), Lajos Kossuth, who after the battle of Isaszeg, went to Gödöllő (the Hungarian headquarters), wanted a direct attack on Pest, finally was convinced by Görgei that his and the other generals plan is better.[11] To secure the succes of the Hungarian army, the National Defense Committee sent from Debrecen 100 wagons with munitions.[12] At 10 April the III. Hungarian army corps, led by General János Damjanich defeated in the Battle of Vác the Ramberg division led by Major General Christian Götz, who was fatally wounded.[13] The imperial high commandment led by Field Marshal Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz even after this battle, was unsure if the main Hungarian army stayed before Pest of it already moved towards north, wanting to relieve Komárom. They still believed in the possibility that only a secondary unit attacked Vác, and moves towards the besieged Hungarian fortress.[14] When Windisch-Grätz finally seemed to grasp what is happening in reality, wanting to make a powerful attack at 14 April against the Hungarians at Pest, than to cross the Danube at Esztergom, and cut the way of the army which was marching towards Komárom, but his corps commanders, General Franz Schlik and Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić refused to obey to his commands, so his plan, which could cause serious problems to the Hungarian armies, was not realized.[15]

Windisch-Grätz, to hold the Hungarian advancement in West towards Komárom, sent order to Lieutenant General Ludwig von Wohlgemuth to stop with the reserve corps formed from the dispensable imperial troops from Vienna, Styria, Bohemia and Moravia the Hungarian armies advancement to Komárom.[16] But when these happened, Windisch-Grätz was not in Hungary, because in the meanwhile, at 12 April he was relieved from the high commandment of the imperial troops in Hungary, by the emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, in his place being designed Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden, the former military governor of Vienna, but until he arrived, Windisch-Grätz had to give the leadership to Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić, as temporary main commander of the imperial armies in Hungary.[17] But this change in the commandment of the imperial forces, had not brought lucidity and organization in the imperial commandment, because the first thing that Jelačić gave after the commencement of his interim High Commandment was to call off Windisch-Grätz's plan of establishing the gathering point of the imperial armies around Esztergom, and with this to give a chance to this not bad plan.[18]

Görgey who after the battle of Győr installed his headquarters in the city, at 11 April gave order to the III. corps of Damjanich, at the 12th to Klapka's I. corps to advance towards Léva. Their place in Vác was taken by the VII. corps under András Gáspár, than after they too departed on the same way, their place in Vác was taken by the division of György Kmety.[19]

Prelude

The three brigades gathered by Lieutenant General Ludwig von Wohlgemuth from the Austrian Hereditary Provinces neared the Vág and Garam rivers, receiving a brigade from the division of Lieutenant General Balthasar Simunich and the Jablonowski division defeated at Vác some days earlier. Welden was sure, that this Austrian army corps, now containing around 20 000 men, would stop the Hungarian advancement.[20] But the contradictory orders given by Welden and Jelačić, prevented that this corps to arrive on time in the vicinity of the Garam river.[21] Welden on 17 April gave him order to march towards Vác, and enter in contact with Wohlgemuth, but the Croatian ban was not very willingly to obey, agreeing to move only in 20 April (a day after the battle of Nagysalló actually took place).[22]

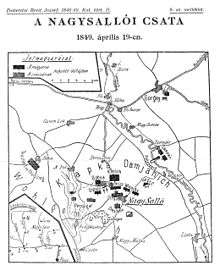

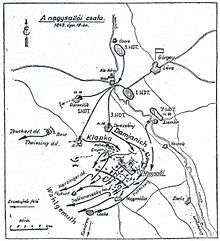

In the meanwhile at 15–17 April the Hungarian army consisting of the I. corps led by General György Klapka, III. corps led by General János Damjanich, and two divisions of the VII. corps led by General András Gáspár arrived to the Garam river, under the overall leadership of General Artúr Görgei. He sent a detachment of 2300 soldiers and 10 batteries to the north, under the command of his older brother Ármin Görgei to occupy the so called Mining Towns (among others: Selmecbánya, Körmöcbánya, Besztercebánya), and to assure the Hungarian troops from an attack from north.[23] Görgei also gave order to the three army corps to make bridges in three separate place across Garam. Because the bridge of the I. corps was finished quickly, while the works at the other two were advancing very slowly, Görgei on the 18th ordered that the III. corps too to cross on the bridge made by the I at Nagykálna, so only the VII. remained on the other side, trying to finish their bridge at Zsemlér. Than the I. and the III. corps advanced towards South-West.[24] In that same day the Dessewffy division of the I. corps occupied Nagysalló.[25]

The Austrian troops of Wolgemuth were positioned as follows: the Veigl brigade at Bese, the Herzinger brigade at Cseke, the Strastil, Dreyhann brigades of the Jablonowski division and the Theissing brigade at Nagymálas, and the Perin brigade at Köbölkút.[26] In a letter to the high command, written at 16 April at 12 o'clock at midnight reports the number of the Hungarian troops to be 24 000 soldiers, with 48 batteries, among them a 12 font cannon, their purpose being to advance towards Komárom, which shows that he made the reconnaissance of the enemy in a quite good way, having an approximately exact knowledge of their numbers and intentions.[27] In the same letter he writes that he hopes, that they will be slow at the crossing of the river, so he wants to face them before they arrive to Nyitra.[28] Welden wrote him back to attack the Hungarian troops, because the high commander taught that this will rise the spirit of the imperial soldiers and will scare the Hungarians.[29] Welden also heard about the possible intervention of the troops of the Russian Empire on behalf of the Habsburg Empire to crush the Hungarian War of Independence, and that some of the czar's troops even entered in the Habsburg province of Galicia, for any eventuality if the Austrians will be in a hopeless situation.[30] But Welden did not wanted that the Austrians to suffer the shame that they could only defeat the Hungarians with Russian help: What we can achieve with our own power, its more than the brightest result, which we can achieve with foreign help.[31] This is also one of the causes he was encouraging Wohlgemuth to enter in fight with the Hungarians.[32]

Battle

On the dawn of 19 April, Wohlgemuth gave order to the Strastil brigade to attack Nagysalló, which accomplished this task, chasing out Klapka's vanguards from the village.[33] This decided to retake the settlement, and announced also Damjanich about this.[34]

the fights started at 10 o'clock with a heavy artillery duel, than two divisions of the I. Hungarian corps, with a bayonet charge, after an hour of fights, forced the Strastil brigade to retreat.[35] The imperial brigade retreated to south-west from Nagysalló.[36] Wohlgemuth ordered them to counter attack, sending also the Dreyhann brigade from Nagymálas in help. The two brigades entered in the village, but they were pushed out.[37] Major General Felix Jablonowski ordered to these two brigades to retreat on the heights to the South West from the village.[38]

In this moment the Hungarians right wing was attacked by the Herzinger brigade from Cseke, which sweeped away the Hungarian Dipold brigade, and pushed it back to the forrest from Hölvény (outside of Nagysalló). But here the Bobich brigade stopped them, while the retreating Hungarian brigade also stopped and regrouped.[39] Here these two brigades were taken over by Major General Richard Guyon (who was not supposed to participate in the battle, because he was designate as the new commander of the besieged troops of Komárom, just wanted to fight, and help his army to obtain the victory).[40] The two Hungarian brigades under the lead of Guyon forced the Herzinger brigade to retreat.[41]

Around 3 o'clock started the Hungarian general attack under the lead of János Damjanich. Wohlgemuth, seeing his troops lack of success, was thinking to retreat, but he was waiting that the Veigl and Perin brigades who advanced from Bese and Köbölkút towards Jászfalu, to join the main army, but in this right moment on his right flank appeared the cavalry of the VII. Hungarian corps, led by Colonel Ernő Poeltenberg.[42] Their bridge on Garam made at Zsemlér being ready, at 7 o'clock in the morning the VII. corps started to cross it. General András Gáspár, hearing the gunfire, urged his troops to cross to hurry, and join the battle. He ordered his troops to join the battle to left from Nagysalló: the artillery and cavalry to help the III. corps, while the brigade of Poeltenberg in the village to observe the road towards Zselíz.[43] The troops of Gáspár, which crossed after this, marched also towards Nagysalló. Two Hungarian battalions, positioned to left from the village, tried to encircle the village, forcing the remaining imperial troops to retreat from it. The Hungarian artillery shot so skillfully the enemy artillery that this was forced to retreat.[44] The retreating imperial artillery tried to take position further back, but after the sappers of the VII. corps made bridges on two ditches, the Hungarian artillery advanced and drove them away again.[45]

In the meanwhile the 4th Sándor Hussar Regiment led by Poeltenberg, together with the cavalry of the III. corps, led by General József Nagysándor, with a cavalry battalion, appeared on the right flank of the imperials.[46] Their attack obliterated the imperial cavalry.[47] The Austrians retreated to Nagymálas, being pursued by the Hungarian army.[48] Here the cavalry attacked again, while a part of the infantry with a battery encircled the village from left, and two half batteries advanced on the road.[49] In this moment from the woods of Nagymálas charged out an imperial battalion, but the fire of the Hungarian artillery disintegrated them, and drove them in the village.[50] But because the imperial troops gathered in Nagymálas were bombarded from the front and sides, they retreated from the village, and took position behind it.[51]

The lead of the Hungarian troops was taken by Lieutenant-Colonel Lajos Zámbelly, the chief of army staff of the VII. corps, who sent two battalions in the woods near the village, to attack from sides the imperials fighting there.[52] In the meanwhile Gáspár commanded on the left wing, and than, joining with Zámbelly's units, entered in Nagymálas pushing out from it the imperials, chasing them to Farnad. Here the Hungarian artillery again took the leading role, and fired on the enemy, which broke in two, one part of them fleeing to Jászfalu, the other in the woods from Cseke.[53] Than the bigger part was chased by the cavalry of the III. corps, while the smaller by Zámbelly's troops with three companies of Sándor hussars, taking around 1000 prisoners.[54]

The left wing of the imperial army could not participate in the battle, because Wohlgemuth failed to withdraw his troops in the right time.[55] But the four brigades he could use, fought in a very brave way.[56]

Görgey did not led his troops in the battle, he let the commanders of his army corps to work together freely, without being conducted by his orders.[57] And despite of that, this battle demonstrated that the Hungarian army can fight in a perfectly coordinated way, without committing the mistakes of the previous battles when different officers showed different levels of taking decisions of their own, when the unexpected situation requires it, like for example in the Battle of Isaszeg. In this battle Klapka, Damjanich, and Gáspár, three generals with very different temperaments (Damjanich being very impulsive, taking decisions in the battle in a moment and fulfilling them, without thinking the risk, Klapka, an old fashioned Habsburg-type general, who put a big importance on the safety of his troops,[58] as well like Gáspár, who was sometimes obeying to the orders taken before from his superiors, even if the situation on the ground urged him to move differently for the sake of the battle[59]) showed a perfect coordination and the capability of taking correct decisions when the situation required, which assured the success for the Hungarian army.[60] The cavalry also did his best in the pursuing of the fleeing enemy at the end of the battle.[61] This is why the Battle of Nagysalló is considered one of the best executed battles of the Hungarian Independence war.[62][63]

Aftermath

The imperial losses were heavy. While Wohlgemuth reported 112 death, 195 wounded and 1243 missing soldiers, the Hungarian military reports, only among captured Austrian soldiers show not less than 1200 people. The Hungarian VII. corps reported that only they captured 5 officers, 1 chief medical officer and 500 soldiers.[64] The Hungarian sources show the imperial losses as 2000 soldiers. The Hungarian losses were shown by György Klapka as 600, while Richárd Gelich as 700.[65]

Görgey was satisfied with the result of the battle, writing after the battle: The spirit of our troops is excellently good. The victory enthuses and keeps alive all the defenders of the homeland, who endure and suffer all the vicissitudes and hardships of the war, and look with high spirits to the events of the future.[66]

This defeat forced Wohlgemuth to lead his army not towards Komárom, where he planned to join the besieging Austrians, but to retreat towards Érsekújvár.[67] Two days after the battle, at 21th April, the first Hungarian units entered in Komárom, ending the imperial blockade from the northern side of the fortress.[68] On 24th Lieutenant General Balthasar von Simunich informed Lieutenant General Anton Csorich that the Hungarians had reconstructed the bridge across the Danube, and on it and on rafts started to cross the river. So he asked him to come with his troops at the latest in the morning of 25 April to Herkálypuszta, to help him against the Hungarian attack.[69] In the next day, in 26th, the Hungarian troops attacked the besieging imperial army from Komárom, which ended in the retreat of the Austrian army towards West, so the main purpose of the Spring Campaign - the liberation of the Western part of Hungary - was fulfilled.[70]

The victory of Nagysalló, brought with itself serious results. It opened the way towards Komárom, bringing its relieving to just a couple of days distance.[71] In the same time it brought the imperials in the situation of being incapable to stretch their troops on a very large front which this Hungarian victory created, so instead of uniting their troops around Pest and Buda, as they planned, Feldzeugmeister Welden had to order the retreat from Pest being in danger to fall in the pincers of the Hungarian troops.[72] When he learned about the defeat in the morning of 20 April, he wrote to Lieutenant General Balthasar Simunich, the commander of the besieging forces of Komárom, and to Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg, the Minister-President of the Austrian Empire, that in order to secure Vienna and Pozsony, from a Hungarian attack, he is forced to retreat the imperial troops from Pest, and even from Komárom.[73] He also wrote that the spirit of the imperial troops is very low, and because of this they cannot fight another battle for a while, without suffering another defeat.[74] So the next day he ordered the evacuation of Pest, leaving an important garrison in the fortress of Buda, to defend it against the Hungarian attacks. He ordered to Jelačić to remain for a while in Pest, and than to retreat towards Eszék in Bácska where the Serbian insurgents, allied with the Austrians were in a grave situation after the victories of the Hungarian armies led by Mór Perczel and Józef Bem.[75]

Notes

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 245.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 245.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 245.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 245.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 233–236.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 235.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 284.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 285.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 285.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 285.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 290.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 285.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 285.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 285.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 287.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 287.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 287.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 287.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 293.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 293.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 293.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 293.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 292.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 293.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 294.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 294.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 242–243.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 294.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 294.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 294.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 301.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 289–290.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 226–227.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 295.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 295.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 295.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 289.

- ↑ Bánlaky József: A magyar nemzet hadtörténete XXI, Magyarország 1848/49. évi függetlenségi harcának katonai története Arcanum Adatbázis Kft. 2001

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 291.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 291–292.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 294-295.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 300–301.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 301.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 291.

Sources

- Bánlaky, József (2001). A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme ("The Military History of the Hungarian Nation) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Arcanum Adatbázis.

- Bóna, Gábor (1987). Tábornokok és törzstisztek a szabadságharcban 1848–49 ("Generals and Staff Officers in the War of Freedom 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi Katonai Kiadó. p. 430. ISBN 963-326-343-3.

- Hermann (ed), Róbert (1996). Az 1848–1849 évi forradalom és szabadságharc története ("The history of the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Videopont. p. 464. ISBN 963-8218-20-7.

- Hermann, Róbert (2004). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc nagy csatái ("Great battles of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi. p. 408. ISBN 963-327-367-6.

- Hermann, Róbert (2001). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc hadtörténete ("Military History of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Korona Kiadó. p. 424. ISBN 963-9376-21-3.

- Pusztaszeri, László (1984). Görgey Artúr a szabadságharcban ("Artúr Görgey in the War of Independece") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó. p. 784. ISBN 963-14-0194-4.