Battle of Phủ Hoài

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

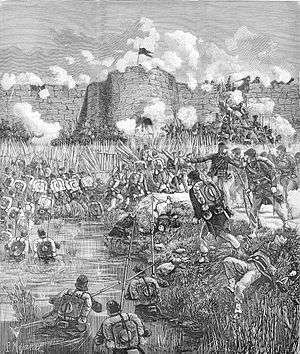

The Battle of Phu Hoai (15 August 1883) was an indecisive engagement between the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps and Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army during the early months of the Tonkin campaign (1883–1886). The battle took place during the period of increasing tension between France and China that eventually culminated in the Sino-French War (August 1884–April 1885).

Background

The Tonkin campaign is conventionally considered to have begun in June 1883, with the decision by the French government to despatch reinforcements to Tonkin to avenge the defeat and death of Henri Rivière at the hands of Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army at the Battle of Paper Bridge on 19 May 1883. These reinforcements were organised into a Tonkin Expeditionary Corps, which was placed under the command of général de brigade Alexandre-Eugène Bouët (1833–87), the highest-ranking marine infantry officer available in the French colony of Cochinchina.

The French position in Tonkin on Bouët's arrival in early June 1883 was extremely precarious. The French had only small garrisons in Hanoi, Haiphong and Nam Dinh, isolated posts at Hon Gai and at Qui Nhon in Annam, and little immediate prospect of taking the offensive against Liu Yongfu's Black Flags and Prince Hoang Ke Viem's Vietnamese.[1] During June the French dug in behind their defences and beat off half-hearted Vietnamese demonstrations against Hanoi and Nam Dinh.[2] The early arrival of reinforcements from France and New Caledonia and the recruitment of Cochinchinese and Tonkinese auxiliary formations allowed Bouët to hit back at his tormentors. On 19 July chef de bataillon Pierre de Badens, the French commandant supérieur at Nam Dinh, attacked and defeated Prince Hoang Ke Viem's besieging Vietnamese army, effectively relieving Vietnamese pressure on Nam Dinh.[3]

The arrival of Admiral Amédée Courbet in Along Bay in July 1883 with substantial naval reinforcements further strengthened the French position in Tonkin. Although the French were now in a position to consider taking the offensive against Liu Yongfu, they realised that military action against the Black Flag Army had to be accompanied by a political settlement with the Vietnamese court at Hue, if necessary by coercion, that recognised a French protectorate in Tonkin. On 30 July 1883 Admiral Courbet, General Bouët and Jules Harmand, the recently appointed French civil commissioner-general for Tonkin, held a council of war at Haiphong. The three men agreed that Bouët should launch an offensive against the Black Flag Army in its positions around Phu Hoai on the Day River as soon as possible. They also noted that the Court of Hue was covertly aiding and abetting Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army, and that Prince Hoang was still in arms against the French at Nam Dinh. They therefore decided, largely on Harmand's urging, to recommend to the French government a strike against the Vietnamese defences of Hue, followed by an ultimatum requiring the Vietnamese to accept a French protectorate over Tonkin or face immediate attack. The proposal was approved by the navy ministry on 11 August, and on 20 August, in the Battle of Thuan An, the French stormed the forts at the mouth of the Hue River, allowing them to attack Hue directly if they chose.[4] The Vietnamese asked for an armistice, and on 25 August Harmand dictated the Treaty of Hue to the cowed Vietnamese court. The Vietnamese recognised the legitimacy of the French occupation of Cochinchina, accepted a French protectorate both for Annam and Tonkin and promised to withdraw their troops from Tonkin. Vietnam, its royal house and its court survived, but under French direction.[5]

While Harmand and Courbet were entrenching the French protectorate at Hue, General Bouët attempted to carry out his part of the programme settled at the Haiphong conference of 30 July. On 15 August 1883, Bouët attacked Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army in its strong defensive positions in front of the Day River.

Forces involved

General Bouët committed 2,500 French and Vietnamese soldiers to the attack. The French force consisted of three marine infantry battalions (chefs de bataillon Chevallier, Lafont and Roux), three marine artillery batteries (Captains Isoir, Dupont and Roussel), four companies of Cochinchinese riflemen and around 450 Yellow Flag auxiliaries. The attackers advanced in three separate columns. The left column, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Révillon, consisted of a marine infantry battalion, a supporting company of Cochinchinese riflemen and two artillery sections. It was accompanied by the Yellow Flag auxiliary battalion.[Note 1] The centre column, under the command of Bouët's chief of staff, chef de bataillon Paul Coronnat, consisted of a marine infantry battalion with a supporting company of Cochinchinese riflemen and a marine artillery battery.[Note 2] The right column, under the command of Colonel Bichot, also included a marine infantry battalion, a supporting Cochinchinese rifle company and a marine artillery battery.[Note 3] Bichot's column, whose right flank lay on the Red River, was supported by six French gunboats (Pluvier, Léopard, Fanfare, Éclair, Mousqueton and Trombe) from the Tonkin Flotilla, under the command of capitaine de vaisseau Morel-Beaulieu. Bouët himself marched behind Révillon's column with a small general reserve.[Note 4]

The Black Flag Army seems to have fielded around 3,000 men. Although Liu Yongfu's forces did not substantially outnumber the French, they had built two lines of field fortifications to block the road to Son Tay. The first, outpost, line ran from the village of Cau Giay near Paper Bridge, the scene of Rivière's defeat and death on 19 May, to the Pagoda of the Four Columns (Quatre Colonnes) on the Red River. The main line of defence ran behind it, taking in the villages of Phu Hoai, Noi and Hong.

The battle

Révillon's left column unsuccessfully attacked the right of the Black Flag line and was counterattacked in its turn by Liu Yongfu and the bulk of the Black Flag Army. As ammunition was running short the French fell back towards Paper Bridge. Their retreat nearly turned into a rout, as the Vietnamese coolies with the column streamed to the rear in panic, blocking the dyke paths along which fresh supplies of ammunition were being brought forward. However, Chevallier's marine infantry battalion, firing from sheltered positions in the village of Vong, successfully covered the French withdrawal, inflicting heavy casualties on Black Flag units that left their defences and ventured out into the open. Towards nightfall Bouët committed his reserve, enabling Révillon to stabilise his line. Having heard no news of the progress of the other two columns, Bouët ordered Révillon's column to return to Hanoi the same evening.

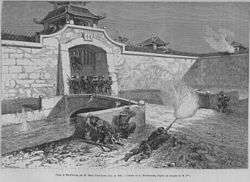

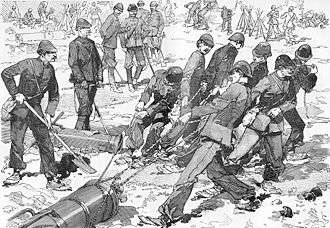

The reason that Liu Yongfu was able to make such a powerful counterattack against Révillon's column was because the other two French columns failed to put serious pressure on the enemy. Coronnat's centre column failed to make contact with the Black Flags at all, while Bichot's right column succeeded in capturing the village of Trem but was then held up in front of the Black Flag defences at Quatre Colonnes. On 16 August Bichot advanced to attack Quatre Colonnes, only to find that the Black Flags had abandoned their positions during the night. The battle had been fought in pouring rain, and during the night of 15 August the Red River burst its banks and began to flood the plains between Hanoi and Phu Hoai. The flooding effectively brought the battle to an end. Neither Coronnat nor Bichot was able to make any further headway on 16 August. Coronnat's column returned to Hanoi, while Bichot contented himself with occupying Quatre Colonnes and bringing back to Hanoi a number of cannon abandoned by the Black Flags in their retreat. The French would later claim that the floods had prevented them from inflicting a major defeat upon Liu Yongfu. In fact, the flooding was a disaster for the Black Flag Army. Liu Yongfu had to abandon his entrenchments in front of the Day River and fall back behind the river, leaving behind all his material and all his wounded.

French casualties in the Battle of Phu Hoai were 17 dead (including 2 officers) and 62 wounded. The French estimated Black Flag casualties at around 300 dead and 800 wounded.[6]

Significance

Although the French severely mauled the Black Flag Army during the battle and suffered relatively low casualties in return, their failure to win a clear victory against Liu Yongfu was widely noted. Although the atrocious weather was the most important reason for the failure of Bouët's attack, poor French command decisions and the extremely stubborn defence put up by the Black Flags were also contributory factors. The indecisive outcome of the battle discouraged many ordinary Tonkinese from supporting the French against the Black Flags, and in the eyes of the world was tantamount to a French defeat.[7]

Notes

- ↑ Révillon’s column included Chevallier's marine infantry battalion, the 1st Annamese Rifle Company (Captain de Beauquesne), 450 Yellow Flags, and two sections of Isoir's battery. Chevallier's battalion consisted of the 25th, 34th and 36th Companies, 1st Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Poulnot, Larivière and Lombard).

- ↑ Coronnat's column included Lafont's marine infantry battalion, the 3rd Annamese Rifle Company (Captain Berger) and Dupont's battery. Lafont's battalion consisted of the 26th, 29th and 33rd Companies, 2nd Marine Infantry Regiment (Lieutenant Goldschoen and Captains Jay and Trilha).

- ↑ Bichot's column included Roux's marine infantry battalion, the 4th Annamese Rifle Company (Captain Serre de Bazaugour) and Roussel's battery. Roux's battalion consisted of the 25th, 26th and 30th Companies, 4th Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Drouin, Taccoën and Martellière).

- ↑ Bouët’s reserve consisted of the 21st Company, 3rd Marine Infantry Regiment (Captain Buquet), the 2nd Annamese Rifle Company (Captain Boutet) and an artillery section (2nd Lieutenant Simon).

Footnotes

- ↑ Duboc, 139–51; Huard, 83–4; ; Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 59–60

- ↑ Huard, 84–8

- ↑ Duboc, 156–7; Huard, 88–92; Nicolas, 262–4

- ↑ Huard, 103–22; Nicolas, 280–5; Thomazi, Conquête, 165–6; Histoire militaire, 62–4

- ↑ Huard, 122–30; Thomazi, Conquête, 166

- ↑ Bastard, 189–97; Duboc, 162–78; Huard, 99–103; Lung Chang, 151-2; Nicolas, 264–77; Thomazi, Conquête, 163–5; Histoire militaire, 60–62

- ↑ Huard, 103

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sino-French War. |

- Bastard, G., Défense de Bazeilles, suivi de dix ans après au Tonkin (Paris, 1884)

- Duboc, Emile, Trente cinq mois de campagne en Chine, au Tonkin (Paris, 1899) OCLC 419559712

- Huard, L., La Guerre du Tonkin (Paris, 1887) OCLC 22485334

- Lung Chang, Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng [Vietnam and the Sino-French War] (Taipei, 1993)

- Nicolas, V., Livre d'or de l'infanterie de la marine (Paris, 1891) OCLC 36848613

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l’Indochine française (Hanoi, 1931) OCLC 491248510

- Thomazi, A., La Conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934) OCLC 154148440