Amédée Courbet

| Amédée Courbet | |

|---|---|

Admiral Anatole-Amédée-Prosper Courbet (1828–85) | |

| Born |

26 June 1827 Abbeville, Picardy, France |

| Died |

11 June 1885 (aged 57) |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1849–1885 |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Commands held | Far East Squadron |

| Battles/wars |

Sino-French war Battle of Thuan An Son Tay Campaign Battle of Fuzhou Keelung Campaign Battle of Shipu Battle of Zhenhai Pescadores Campaign |

| Awards |

Grand Officer of the Légion d'honneur Médaille militaire |

Anatole-Amédée-Prosper Courbet (26 June 1827 – 11 June 1885) was a French admiral who won a series of important land and naval victories during the Tonkin campaign (1883–86) and the Sino-French War (August 1884–April 1885).

Early years

Courbet was born in Abbeville as the youngest of three children. His father died when he was nine years old. He was a Polytechnician.

From 1849 to 1853 Courbet served as a midshipman (aspirant) on the corvette Capricieuse (capitaine de vaisseau Roquemaurel). Capricieuse circumnavigated the globe during this period and cruised for several months along the China Coast, giving Courbet his first experience of the seas in which, thirty years later, he would win fame. After his return to France he was posted to the brick Olivier, attached to the Levant naval division. In December 1855, at Smyrna, he intervened to quell a mutiny aboard the Messageries impériales packet Tancrède, and was subsequently commended for his conduct by the navy ministry. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant de vaisseau in November 1856.

From 1864 to 1866 Courbet served on the two-deck broadside ironclad battleship Solferino as aide de camp and secretary to Admiral Bouët-Willaumez, commander of the escadre d’évolutions. He was promoted capitaine de frégate in August 1866 and posted to the ironclad frigate Savoie as chief of staff to Admiral de Dompierre d’Hornoy, commander of the North Sea and English Channel naval division. In March 1870 he was posted to the Antilles naval division as captain of the despatch vessel Talisman. This posting, which gave him no opportunity for action during the Franco-Prussian War, was his first independent command. He returned to France in May 1872.

In early 1873 Courbet returned to the Antilles as second officer on the frigate Minerve. He was promoted capitaine de vaisseau in August 1873. Between December 1874 and January 1877 he commanded the School of Underwater Defences (école des défenses sous-marines) at Boyardville (Ile d’Oléron). From 1877 to 1879 he was posted to the ironclad Richelieu, where he again served as chief of staff to Admiral de Dompierre d’Hornoy, now commander-in-chief of the escadre d’évolutions.

In May 1880 Courbet succeeded Admiral Olry as governor of New Caledonia. He returned to France in the autumn of 1882, where he was promised command of the Levant naval division by Admiral Bernard Jauréguiberry, the navy minister. Jauréguiberry was replaced as navy minister in January 1883 when Charles Duclerc's cabinet was replaced by the brief administration of Armand Fallières, and Courbet was instead appointed commander of the division navale d’essais in the Mediterranean. In April 1883 he hoisted his flag aboard the ironclad Bayard at Cherbourg.

Command of Tonkin Coasts Naval Division

In June 1883 Courbet was transferred from the division navale d’essais and given command of a new Tonkin Coasts naval division (division navale des côtes du Tonkin). The French government was attempting to impose a protectorate in Tonkin (northern Vietnam) at this period, in the face of bitter opposition from Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army. The Black Flag Army was covertly armed and supplied by China, and the role of the new naval division was to cut the flow of weapons and ammunition to the Black Flags by blockading the Gulf of Tonkin. The Tonkin Coasts naval division included the ironclads Bayard and Atalante from Courbet's Mediterranean command and the cruiser Châteaurenault from Algiers. Courbet was also given two torpedo boats, Nos. 45 and 46, and was ordered to take over the seagoing vessels of the Cochinchina naval division on his arrival in Tonkin. Courbet arrived at Along Bay in July 1883.

In August in response to the death of the Vietnamese emperor Tự Đức and a consequent succession crisis, the French government approved an operation to coerce the Vietnamese court at Huế. On 18 August Courbet's naval division bombarded the Thuan An forts at the entrance to the River of Perfumes, and on 20 August, in the Battle of Thuan An, a landing force of sailors and marine infantry overran the Vietnamese defences and captured the forts. Courbet's victory, which enabled the French to occupy Huế whenever they wanted, compelled the Vietnamese court to submit to French authority and sign the Treaty of Huế, which recognised the French protectorate in Tonkin.[1]

Command of Tonkin Expeditionary Corps

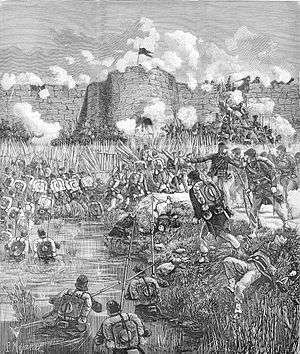

In October 1883 Courbet was placed in command of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps. In December 1883 he struck at Son Tay. The Son Tay Campaign was the fiercest campaign the French had yet fought in Tonkin. Although the Chinese and Vietnamese contingents at Son Tay played little part in the defence, Liu Yongfu's Black Flags fought ferociously to hold the city. On 14 December the French assaulted the outer defences of Son Tay at Phu Sa, but were thrown back with heavy casualties. Hoping to exploit this reverse, Liu Yongfu attacked the French lines the same night, but the Black Flag attack also failed disastrously. After resting his troops on 15 December, Courbet again assaulted the defences of Son Tay on the afternoon of 16 December. This time the attack was thoroughly prepared by artillery, and delivered only after the defenders had been worn down. At 5 p.m. a Foreign Legion battalion and a battalion of marine fusiliers captured the western gate of Son Tay and fought their way into the town. Liu Yongfu's garrison withdrew to the citadel, and evacuated Son Tay under cover of darkness several hours later. Courbet had achieved his objective, but at considerable cost. French casualties at Son Tay were 83 dead and 320 wounded. The fighting at Son Tay also took a terrible toll of the Black Flags, and in the opinion of some observers broke them once and for all as a serious fighting force.[2]

Command of Far East Squadron

The 1883 campaigns in Tonkin had been conducted, like most French colonial enterprises, by the troupes de marine, and had been overseen by the navy ministry. In December 1883, however, in view of the increasing commitment of troops from Algeria to Tonkin, the army ministry insisted on appointing a general from the regular army to command of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps, which would be henceforth be constituted as a two-brigade infantry division with the normal complement of artillery and other supporting arms. Jules Ferry's cabinet approved this recommendation, and Courbet was replaced in command of the expeditionary corps on 16 December 1883 by General Charles-Théodore Millot—ironically, on the very day on which he captured Son Tay. He resumed command of the Tonkin Coasts naval division, and for the next six months played a most unwelcome subordinate role, hunting down bands of Vietnamese pirates in the Gulf of Tonkin while Millot was winning glory in the Bac Ninh campaign.[3]

Courbet's luck changed in June 1884. On 27 June, in response to the news of the Bac Le ambush, the Tonkin Coasts naval division and the Far East naval division were amalgamated into a Far East Squadron. The new squadron, which would remain in existence throughout the Sino-French War, was placed under Courbet's command, with Admiral Sébastien Lespès (the commander of the Far East naval division) second in command. Courbet's squadron initially included the ironclads Bayard (the flagship), Atalante, La Galissonnière and Triomphante, the cruisers Châteaurenault, d'Estaing, Duguay-Trouin and Volta, the light frigates Hamelin and Parseval, the gunboats Lynx, Vipère, Lutin and Aspic, the troopships Drac and Saône and Torpedo Boats Nos. 45 and 46. In July 1884 Courbet was ordered to concentrate part of the squadron at Fuzhou, to threaten the Fujian fleet (one of China's four regional fleets) and the Foochow Navy Yard.[4]

Min River operations, August 1884

Negotiations between France and China to resolve the crisis over the Bac Le ambush broke down in mid- August and on 22 August Courbet was ordered to attack the Chinese fleet at Fuzhou. In the Battle of Fuzhou (also known as the Battle of the Pagoda Anchorage) on 23 August 1884, Courbet's Far East Squadron annihilated China's outclassed Fujian fleet and severely damaged the Foochow Navy Yard. Nine Chinese ships were sunk in less than an hour, including the corvette Yangwu, the flagship of the Fujian fleet. Chinese losses may have amounted to 3,000 dead, while French losses were minimal. Courbet then successfully withdrew down the Min River to the open sea, destroying several Chinese shore batteries from behind as he took the French squadron through the Min'an and Jinpai passes.[5]

Operations in Formosa, October 1884

In late September 1884, much to his distaste, Courbet was ordered to use the Far East Squadron to support the landing of a French expeditionary corps at Keelung and Tamsui in northern Formosa (Taiwan). Courbet argued vigorously against a campaign in Formosa and submitted alternative proposals to the navy ministry for a campaign in northern Chinese waters to seize Port Arthur or Weihaiwei. He was supported by Jules Patenôtre, the French minister to China, but both men were overruled.[6]

On 1 October Lieutenant-Colonel Bertaux-Levillain landed at Keelung with a force of 1,800 marine infantry, forcing the Chinese to withdraw to strong defensive positions which had been prepared in the surrounding hills. The French force was too small to advance beyond Keelung. Meanwhile, after an ineffective naval bombardment on 2 October, Admiral Lespès attacked the Chinese defences at Tamsui with 600 sailors from his squadron's landing companies on 8 October, and was decisively repulsed by forces under the command of the Fujianese general Sun Kaihua (孫開華). The French were now committed to a prolonged Keelung Campaign, and Courbet's squadron was tied down in a largely ineffective blockade of Formosa.

Battle of Shipu Bay, February 1885

After several months of inactivity, Courbet won a series of victories in the spring of 1885. Courbet's squadron had been reinforced substantially since the start of the war, and he now had considerably more ships at his disposal than in October 1884. In early February 1885 part of his squadron left Keelung to head off a threatened attempt by part of the Chinese Southern Seas fleet to break the French blockade of Formosa. On 11 February Courbet's task force met the cruisers Kaiji, Nanchen and Nanrui, three of the most modern ships in the Chinese fleet, near Shipu Bay, accompanied by the frigate Yuyuan and the composite sloop Chengqing. The Chinese scattered at the French approach, and while the three cruisers successfully made their escape, the French succeeded in trapping Yuyuan and Chengqing in Shipu Bay. On the night of 14 February, in the Battle of Shipu, both ships were crippled during a daring French torpedo attack, Yuyuan by a French spar torpedo and Chengqing by Yuyuan's fire. Both ships were subsequently scuttled by the Chinese.[7]

Blockade of Ningbo, March 1885

Courbet followed up this success on 1 March by locating Kaiji, Nanchen and Nanrui, which had taken refuge with four other Chinese warships in Zhenhai Bay, near the port of Ningbo. Courbet considered forcing the Chinese defences, but finally decided to guard the entrance to the bay to keep the enemy vessels bottled up there for the duration of hostilities. A brief and inconclusive skirmish between the French cruiser Nielly and the Chinese shore batteries on 1 March enabled the Chinese general Ouyang Lijian, charged with the defence of Ningbo, to claim the so-called Battle of Zhenhai as a defensive victory.[8]

Rice blockade, March–June 1885

In February 1885, under diplomatic pressure from China, Britain invoked the provisions of the 1870 Foreign Enlistment Act and closed Hong Kong and other ports in the Far East to French warships. The French government retaliated by ordering Courbet to implement a 'rice blockade' of the Yangzi River, hoping to bring the Qing court to terms by provoking serious rice shortages in northern China. The rice blockade severely disrupted the transport of rice by sea from Shanghai and forced the Chinese to carry it overland, but the war ended before the blockade seriously affected China's economy.

Pescadores campaign, March 1885

A major French victory at Keelung in early March 1885 enabled Courbet to detach a marine infantry battalion and a marine artillery section from the Keelung garrison to capture the Pescadores Islands in late March. Courbet directed operations in person, and this brief colonial campaign was fought in the traditional style, by ships of the French navy and by the troupes de marine. Strategically, the Pescadores Campaign was an important victory, which would have prevented the Chinese from further reinforcing their army in Formosa, but it came too late to affect the outcome of the war. A proposal to use the Far East squadron to make a landing in the Gulf of Petchili was cancelled on the news of the French defeat in the Battle of Bang Bo (24 March 1885) and the subsequent retreat from Lang Son, and Courbet was on the point of evacuating Keelung to reinforce the Tonkin expeditionary corps, leaving only a minimum garrison at Makung in the Pescadores, when hostilities came to an end in April 1885.[9]

Courbet's death and state funeral, June–September 1885

The French occupied the Pescadores until July 1885. Courbet and several dozen other French soldiers and sailors died of cholera during the brief French occupation. He had already suffered a severe bout of dysentery in April 1885, and his health declined rapidly during the next two months. On 8 June he walked with his head bared under the hot sun of the Pescadores in the funeral procession of sous-commissaire Dert, a marine infantry officer who had just died of cholera, and this duty critically weakened him. He died aboard his flagship Bayard in Makung harbour on the night of 11 June 1885. Admiral Sébastien Lespès assumed command of the Far East Squadron, and presided at a memorial service for Courbet at Makung on 13 June.[10]

On 23 June Bayard left Makung, to a 19-gun salute from more than thirty French warships, to take Courbet's body back to France for a state funeral in Paris. After a two-month voyage back to France that included stops at Singapore, Mahé (in the Seychelles), Aden, Suez, Alexandria and Bône, Bayard reached the coast of Provence on 24 August and joined the French Mediterranean fleet in the harbour of Les Salins d'Hyères. Courbet's coffin was ceremoniously landed on 26 August, and taken in state to Paris aboard a special train. At Avignon and other stations on the route to Paris patriotic crowds lined the route, eager to pay their last respects to France's most famous admiral. A state funeral for Courbet was held at Les Invalides on 27 August. The funeral oration was pronounced by Charles Émile Freppel, bishop of Angers, one of the most fervent supporters of Jules Ferry's policy of colonial conquest in Tonkin. Courbet's body was then taken by train to his home town of Abbeville in Picardy, where a burial service was held on 1 September. Following a further oration by bishop Freppel, the final eulogy to Courbet was delivered in Abbeville's collegiate church of Saint Vulfran by the recently appointed navy minister, Admiral Charles-Eugène Galiber.[11]

Courbet's leadership

Courbet was a cautious, methodical commander, who calculated the odds carefully before committing his men to battle. Wherever possible he sought to minimise French casualties, and on several occasions he cancelled an attack which he had previously ordered. He was a deeply private individual, who discouraged familiarity from his subordinates, both officers and men. At the same time, he was deeply respected and loved. One of the sailors of the Far East Squadron summed up the reason why he was so popular: 'Admiral Courbet is a great man. He doesn't get his men killed for nothing!'[12]

Colonel Thomazi, commenting on the French government's choice of Courbet to command the Tonkin Seas naval division in 1883, gave a perceptive analysis of Courbet's approach to leadership:

Rear Admiral Courbet, then aged 56, had enjoyed rapid promotion, although by a remarkable chance he had never taken part in any military operation. He had been in the Levant during the Crimean War, and had taken part neither in the Italian War nor the China and Mexico expeditions. In 1870 and 1871 he had been in the Antilles. But his naval career had been extremely active. He had sailed all of the world's oceans, had exercised numerous commands, and had won the reputation of a first-class tactician. He had not wished to specialise in one particular branch of naval science, but had studied them all deeply, from astronomy and gunnery to engines and torpedoes. He was the model of a well-rounded officer, familiar with everything which concerned his profession.

He was as judicious as wise, as helpful as intelligent. He studied with minute care the problems to be resolved, weighed his decision carefully, and when he had made it carried it out with inflexible energy. His orders were short and lucid, and he never shrank from accepting responsibility. While chary in his praises, he was a fair man, and recognised good service in others. As a result he was able to get the best out of his subordinates, and they in turn had complete confidence in him. He was one of those rare men who were born to command others. It is certain that in any other career he would have displayed the same superiority and authority as in the navy. Circumstances would highlight his magnificent leadership qualities.[13]

Enseigne de vaisseau Louis-Marie-Julien Viaud (1850–1923), who served under Courbet's command in Tonkin and described his experiences in a number of popular articles published under the pen name Pierre Loti, discerned Courbet's more human side:

He set a very high price on the lives of the sailors and soldiers, which after two years seemed not to be rated at their true value in far-off France, and begrudged spilling a drop of French blood. His battles were concerted and worked out in advance with such minute precision that the results, often devastating, were always obtained with very small losses on our side. In battle he was stern and unbending, but when the fighting was over he became a different man, a very gentle man, who made his rounds of the hospitals with a fine, sad smile. He wanted to see the wounded, even the most humble of them, and to shake their hands; and they died the happier, comforted by his visit.[14]

Courbet's memory

The old Haymarket Square (Place du Marché-au-Blé) in Courbet's home town of Abbeville was renamed Place de l'Amiral Courbet by the city authorities in July 1885, shortly after the news of Courbet's death reached France.[15] An extravagant baroque statue of Courbet was erected in the middle of the square at the end of the nineteenth century. The statue was damaged in a devastating German bombing raid during the Second World War.

Three ships of the French Navy have been named after Admiral Courbet: an ironclad (Courbet, in service from 1882 to 1909), a battleship (Courbet, in service from 1913 to 1944), and a modern stealth frigate, Courbet (F 712), presently in active service.

French warships named after Admiral Courbet

Decorations

- Légion d'honneur

- Knight (22 October 1857)

- Officer (30 December 1868)

- Commander (23 July 1879)

- Grand Officer (20 December 1883)

- Médaille militaire (13 September 1884)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Loir, 13–22; Thomazi, Conquête, 165–6; Histoire militaire, 62–4

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 171–7; Histoire militaire, 68–72

- ↑ Loir, 29–35

- ↑ Loir, 65–87

- ↑ Lung Chang, 280–3; Thomazi, Conquête, 204–15

- ↑ Garnot, 32–40

- ↑ De Lonlay, 67–90; Duboc, 274–93; Loir, 245–64; Lung Chang, 327-8

- ↑ Loir, 271–84

- ↑ De Lonlay, 55–6; Duboc, 295–303; Garnot, 179–95; Loir, 291–317

- ↑ De Lonlay, 18–27; Garnot, 214–23; Loir, 338–45

- ↑ De Lonlay, 25–27, 37–50, 91–7, 120–136 and 138–63

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 213

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 160

- ↑ Loir, 159

- ↑ De Lonlay, L’amiral Courbet, 138–63

References

- Duboc, E., Trente cinq mois de campagne en Chine, au Tonkin (Paris, 1899)

- Garnot, L'expédition française de Formose, 1884–1885 (Paris, 1894)

- Loir, M., L'escadre de l'amiral Courbet (Paris, 1886)

- Lonlay, D. de, L'amiral Courbet et le « Bayard »: récits, souvenirs historiques (Paris, 1886)

- Lung Chang [龍章], Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng [越南與中法戰爭, Vietnam and the Sino-French War] (Taipei, 1993)

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l'Indochine française (Hanoi, 1931)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)

- Biographie de l'Amiral Courbet (French) Jean-Vincent Brisset fr:Jean-Vincent Brisset