Baylisascaris procyonis

| Baylisascaris procyonis | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Secernentea |

| Order: | Ascaridida |

| Family: | Ascarididae |

| Genus: | Baylisascaris |

| Species: | Baylisascaris procyonis |

| Binomial name | |

| Baylisascaris procyonis | |

| Baylisascaris procyonis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources |

Baylisascaris procyonis, common name raccoon roundworm, is a roundworm nematode, found ubiquitously in raccoons, the definitive hosts. It is named after H. A. Baylis, who studied them in the 1920s–30s, and Greek askaris (intestinal worm).[1] Baylisascaris larvae in paratenic hosts can migrate, causing visceral larva migrans (VLM). Baylisascariasis as the zoonotic infection of humans is rare, though extremely dangerous due to the ability of the parasite's larvae to migrate into brain tissue and cause damage. Concern for human infection has been increasing over the years due to urbanization of rural areas resulting in the increase in proximity and potential human interaction with raccoons.[2]

Transmission

In North America, B. procyonis infection rates in raccoons are very high, being found in around 70% of adult raccoons and 90% of juvenile raccoons.[3] Transmission occurs similarly to other roundworm species, through the fecal-oral route. Eggs are produced by the worm while in the intestine, and the released eggs will mature to an infective state externally in the soil. When an infected egg is ingested, the larvae will hatch and enter the intestine. Transmission of B. procyonis may also occur through the ingestion of larvae found in infected tissue.[3]

Epidemiology

B. procyonis is found abundantly in its definitive host, the raccoon. The parasite has been found to have the ability to infect more than 90 kinds of wild and domestic animals.[3] Many of these animals act as paratenic hosts and the infection results in the penetration of the gut wall by the larvae and subsequent invasion of tissue, resulting in severe disease. In animals, it is the most common cause of larva migrans.[4] The paratenic host, however, cannot shed infective eggs, as the larva will not complete its life cycle until it makes its way into a raccoon. Raccoons are solitary but will frequently defecate in communal areas known as raccoon latrines. These latrines are an abundant source of B. procyonis eggs, which can remain viable for years.[4] Raccoons therefore are important in maintaining the parasite, providing a source of infection for humans and other animals.[4]

The white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) among other small rodents are considered common paratenic hosts.[5] Migration patterns of rodents can explain the spread of Baylisascaris to multiple locations and the subsequent infection of humans who may come into contact with eggs shed by infected raccoons. The mice may be infected as a result of contact with raccoon latrines. Foraging upon food contaminated with traces of raccoon feces can also lead to exposure to B. procyonis eggs. Rodents are easily found in many areas with human population which increases the risk of transmission.[6]

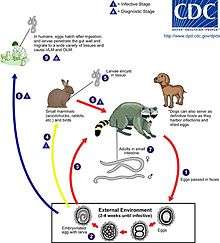

Life cycle

An adult worm lives and reproduces in the intestine of its definitive host, the raccoon. The female worm can produce between 115,000–179,000 eggs per day. Eggs are excreted along with feces, and become infective in the soil after 2–4 weeks. If ingested by another raccoon, the life cycle repeats. However, if these eggs are ingested by a paratenic host (small mammals, birds) the larvae of B. procyonis will penetrate the gut wall of the host and migrate into tissues. Larvae tend to migrate to the brain, cause damage, and affect the behaviour of the intermediate host, making it an easier prey for raccoons. Reproduction does not occur in these paratenic hosts; however, if a raccoon preys on an infected paratenic host, the encysted larvae can become adults in the raccoon and the cycle resumes.[2]

Infection in humans

The potential for human infection was noted in 1969 by Paul C. Beaver, who studied infected mice, and the first case was reported 15 years later.[2] Human infection with B. procyonis has been relatively rare, with about 13 cases reported since 1980. However, disease caused by this parasite can be extremely dangerous, causing death or severe symptoms. Reported disease has primarily afflicted children and almost all cases were a result of the ingestion of contaminated soil or feces.[4] Out of the 13 cases, 5 were fatal and the remaining victims were left with severe neurological damage. Even with treatment, prognosis is poor. The common antihelmintic medicines are able to treat adult worms living in the intestines, but are less potent against migrating larvae. Animal studies have shown that treatment is more effective before the larvae have reached the brain; however, migration to the brain was shown to occur only 3 days after ingestion, leaving a very small window of opportunity.[4] It is possible that human infection is more common than diagnosed and most cases do not reach a clinical stage.[3]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of B. procyonis is through identification of larvae in tissue examination. Diagnosis requires forehand knowledge along with understanding and recognition of larval morphologic characteristics, including ability to distinguish between a number of possible other parasites, including Toxocara canis, Toxocara cati, Ascaris lumbricoides, and among species of Gnathostoma, Angiostrongylus, and Ancylostoma.[3] Distinguishing features of B. procyonis larvae in tissue are its relatively large size (60 μ) and prominent single lateral alae. Sometimes serologic testing is used as supportive evidence, although no commercial serologic test is currently available.

Other diagnosis methods include: brain biopsy, neuroimaging, electroencephalography, differential diagnoses among other laboratory tests.[4]

Human Baylisascariasis is under-recognized, as the knowledge of the clinical illness is still a bit unclear. This could be because of the difficulty of diagnosing the illness. As small numbers of larvae can cause severe disease, and larvae occur randomly in tissue, a biopsy usually fails to include larvae and therefore leads to negative results. The identification of the morphologic characteristics takes practice and experience and may not be accurately recognized or could be misidentified. The fact that no commercial serologic test exists for the diagnosis of B. procyonis infection makes the diagnosis and treatment more difficult.[3]

Prevention

Educating the public about the dangers of contact with raccoons or their feces is the most important preventive step.[4]

Parents should encourage their children to practice good hygiene; Hand-washing after outdoor play or contact with animals is very important. Fences can be used to prevent raccoons from visiting homes, garbage, or yards for food. Keeping raccoons as pets is strongly discouraged. Raccoon latrines in and around homes should be checked for and cleaned as soon as possible. Boiling water, steam-cleaning, flaming, or fire are highly effective and are easily accessible means to decontaminate household things or areas. Materials contaminated by B.procyonis should be incinerated. Contaminated areas can be cleaned with a xylene-ethanol mixture. Common chemical disinfectants are not effective against B.procyonis eggs. Disinfectants like 20% bleach (1% sodium hypochlorite) washes away the eggs but does not kill them. Since treatment is not very effective, the best way to escape this parasite is to practice the prevention methods.[4]

Bioterrorism threat

B. procyonis has become a concern for its potential use as an agent of bioterrorism. The fact that this parasite's eggs are easy to acquire, able to live for years, extremely resistant to many disinfectants and heat, and cause serious infections in humans with poor treatment options could make it a dangerous weapon.[4] Community water supplies are easily susceptible to contaimination due to the lack of filtration and treatment methods to get rid of the eggs.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Carol Snarey (Nov 2010). "Etymologia: Baylisascaris". Emerg Infect Dis. 16 (11): 1819. doi:10.3201/eid1611.ET1611. PMC 3294543

.

. - 1 2 3 Drisdelle R. Parasites. Tales of Humanity's Most Unwelcome Guests. Univ. of California Publishers, 2010. p. 189f. ISBN 978-0-520-25938-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sorvillo, F.; Ash, L. R.; Berlin, O. G.; Morse, S. A. (2002). "Baylisascaris procyonis: An Emerging Helminthic Zoonosis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 355–359. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010273. PMC 2730233

. PMID 11971766.

. PMID 11971766. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Gavin, P. J.; Kazacos, K. R.; Shulman, S. T. (2005). "Baylisascariasis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (4): 703–18. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.4.703-718.2005. PMC 1265913

. PMID 16223954.

. PMID 16223954. - ↑ Beasley, JC et al, (2013) "Baylisascaris procyonis Infections in White- Footed Mice: Predicting patterns of Infection from landscape Habitat Attributes," Journal of Parasitology, 99(5). , p. 743.

- ↑ Beasley, JC et al, (2013). "Baylisascaris procyonis Infections in White- Footed Mice: Predicting patterns of Infection from landscape Habitat Attributes," Journal of Parasitology, 99(5). , p. 745.

- ↑ Sorvillo, Frank. "Baylisascaris procyonis: An Emerging Helminthic Zoonosis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 355–359. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010273. PMC 2730233

. PMID 11971766.

. PMID 11971766.