Filariasis

| Filariasis | |

|---|---|

| |

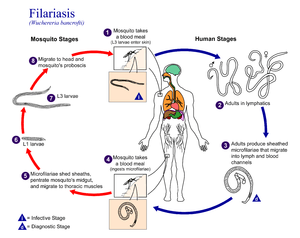

| Life cycle of Wuchereria bancrofti, a parasite that causes filariasis | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | B74 |

| ICD-9-CM | 125.0-125.9 |

| Patient UK | Filariasis |

| MeSH | D005368 |

Filariasis is a parasitic disease caused by an infection with roundworms of the Filarioidea type.[1] These are spread by blood-feeding black flies and mosquitoes. This disease belongs to the group of diseases called helminthiases.

Eight known filarial nematodes use humans as their definitive hosts. These are divided into three groups according to the niche they occupy in the body:

- Lymphatic filariasis is caused by the worms Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. These worms occupy the lymphatic system, including the lymph nodes; in chronic cases, these worms lead to the syndrome of elephantiasis.

- Subcutaneous filariasis is caused by Loa loa (the eye worm), Mansonella streptocerca, and Onchocerca volvulus. These worms occupy the subcutaneous layer of the skin, in the fat layer. L. loa causes Loa loa filariasis, while O. volvulus causes river blindness.

- Serous cavity filariasis is caused by the worms Mansonella perstans and Mansonella ozzardi, which occupy the serous cavity of the abdomen.

The adult worms, which usually stay in one tissue, release early larval forms known as microfilariae into the host's bloodstream. These circulating microfilariae can be taken up with a blood meal by the arthropod vector; in the vector, they develop into infective larvae that can be transmitted to a new host.

Individuals infected by filarial worms may be described as either "microfilaraemic" or "amicrofilaraemic", depending on whether microfilariae can be found in their peripheral blood. Filariasis is diagnosed in microfilaraemic cases primarily through direct observation of microfilariae in the peripheral blood. Occult filariasis is diagnosed in amicrofilaraemic cases based on clinical observations and, in some cases, by finding a circulating antigen in the blood.

Signs and symptoms

The most spectacular symptom of lymphatic filariasis is elephantiasis—edema with thickening of the skin and underlying tissues—which was the first disease discovered to be transmitted by mosquito bites.[2] Elephantiasis results when the parasites lodge in the lymphatic system.

Elephantiasis affects mainly the lower extremities, while the ears, mucous membranes, and amputation stumps are affected less frequently. However, different species of filarial worms tend to affect different parts of the body; Wuchereria bancrofti can affect the legs, arms, vulva, breasts, and scrotum (causing hydrocele formation), while Brugia timori rarely affects the genitals. Those who develop the chronic stages of elephantiasis are usually free from microfilariae (amicrofilaraemic), and often have adverse immunological reactions to the microfilariae, as well as the adult worms.[2]

The subcutaneous worms present with rashes, urticarial papules, and arthritis, as well as hyper- and hypopigmentation macules. Onchocerca volvulus manifests itself in the eyes, causing "river blindness" (onchocerciasis), one of the leading causes of blindness in the world. Serous cavity filariasis presents with symptoms similar to subcutaneous filariasis, in addition to abdominal pain, because these worms are also deep-tissue dwellers.

Cause

Human filarial nematode worms have complicated lifecycles, which primarily consists of five stages. After the male and female worms mate, the female gives birth to live microfilariae by the thousands. The microfilariae are taken up by the vector insect (intermediate host) during a blood meal. In the intermediate host, the microfilariae molt and develop into third-stage (infective) larvae. Upon taking another blood meal, the vector insect injects the infectious larvae into the dermis layer of the skin. After about one year, the larvae molt through two more stages, maturing into the adult worms.

Diagnosis

Filariasis is usually diagnosed by identifying microfilariae on Giemsa stained, thin and thick blood film smears, using the "gold standard" known as the finger prick test. The finger prick test draws blood from the capillaries of the finger tip; larger veins can be used for blood extraction, but strict windows of the time of day must be observed. Blood must be drawn at appropriate times, which reflect the feeding activities of the vector insects. Examples are W. bancrofti, whose vector is a mosquito; night is the preferred time for blood collection. Loa loa's vector is the deer fly; daytime collection is preferred. This method of diagnosis is only relevant to microfilariae that use the blood as transport from the lungs to the skin. Some filarial worms, such as M. streptocerca and O. volvulus, produce microfilarae that do not use the blood; they reside in the skin only. For these worms, diagnosis relies upon skin snips, and can be carried out at any time.

Concentration methods

Various concentration methods are applied: membrane filter, Knott's concentration method, and sedimentation technique.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antigenic assays, which detect circulating filarial antigens, are also available for making the diagnosis. The latter are particularly useful in amicrofilaraemic cases. Spot tests for antigen[3] are far more sensitive, and allow the test to be done any time, rather in the late hours.

Lymph node aspirate and chylus fluid may also yield microfilariae. Medical imaging, such as CT or MRI, may reveal "filarial dance sign" in chylus fluid; X-ray tests can show calcified adult worms in lymphatics. The DEC provocation test is performed to obtain satisfying numbers of parasites in daytime samples. Xenodiagnosis is now obsolete, and eosinophilia is a nonspecific primary sign.

Treatment

The recommended treatment for people outside the United States is albendazole combined with ivermectin.[4][5] A combination of diethylcarbamazine and albendazole is also effective.[4][6] Side effects of the drugs include nausea, vomiting, and headaches.[7] All of these treatments are microfilaricides; they have no effect on the adult worms. While the drugs are critical for treatment of the individual, proper hygiene is also required.[8]

Different trials were made to use the known drug at its maximum capacity in absence of new drugs. In a study from India, it was shown that a formulation of albendazole had better anti-filarial efficacy than albendazole itself.[9]

In 2003, the common antibiotic doxycycline was suggested for treating elephantiasis.[10] Filarial parasites have symbiotic bacteria in the genus Wolbachia, which live inside the worm and seem to play a major role in both its reproduction and the development of the disease. This drug has shown signs of inhibiting the reproduction of the bacteria, further inducing sterility.[11] Clinical trials in June 2005 by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine reported an eight-week course almost completely eliminated microfilaraemia.[12]

Society and culture

Research teams

In 2015 William C. Campbell and Satoshi Ōmura were Co-awarded half of that year's Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of the drug avermectin, which in the further developed form ivermectin has come to decrease the occurrence of lymphatic filariasis.[13]

Other animals

Filariasis can also affect domesticated animals, such as cattle, sheep, and dogs.

Cattle

- Verminous haemorrhagic dermatitis is a clinical disease in cattle due to Parafilaria bovicola.

- Intradermal onchocercosis of cattle results in losses in leather due to Onchocerca dermata, O. ochengi, and O. dukei. O. ochengi is closely related to human O. volvulus (river blindness), sharing the same vector, and could be useful in human medicine research.

- Stenofilaria assamensis and others cause different diseases in Asia, in cattle and zebu.

Horses

- "Summer bleeding" is hemorrhagic subcutaneous nodules in the head and upper forelimbs, caused by Parafilaria multipapillosa (North Africa, Southern and Eastern Europe, Asia and South America).[14]

Dogs

- Heart filariasis is caused by Dirofilaria immitis.

See also

References

- ↑ Center for Disease Control and Prevention. "Lymphatic Filariasis". Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- 1 2 "Lymphatic filariasis". Health Topics A to Z. Source: The World Health Organization. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- ↑ "Seva Fila" (PDF). JB Tropical Disease Research Centre & Department of Biochemistry, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences.

- 1 2 The Carter Center, Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination Program, retrieved 2008-07-17

- ↑ U.S. Centers for Disease Control, Lymphatic Filariasis Treatment, retrieved 2008-07-17

- ↑ Bockarie, Moses; Hoerauf, Achim; Taylor, Mark J. (08 October 2010). "Lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis". The Lancet. 376 (9747): 1175-1185. Check date values in:

|date=(help); - ↑ Turkington, Carol A. "Filariasis". The Gale Encyclopedia of Public Health. 1: 351-353.

- ↑ Hewitt, Kirsten; Whitworth, James AG (1 August 2005). "Filariasis". Medicine. 33 (8): 61–64.

- ↑ Gaur RL, Dixit S, Sahoo MK, Khanna M, Singh S, Murthy PK (2007). "Anti-filarial activity of novel formulations of albendazole against experimental brugian filariasis". Parasitology. 134: 537–44. doi:10.1017/S0031182006001612. PMID 17078904.

- ↑ Hoerauf A, Mand S, Fischer K, Kruppa T, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Debrah AY, Pfarr KM, Adjei O, Buttner DW (2003), "Doxycycline as a novel strategy against bancroftian filariasis-depletion of Wolbachia endosymbionts from Wuchereria bancrofti and stop of microfilaria production", Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl), 192 (4): 211–6, doi:10.1007/s00430-002-0174-6, PMID 12684759

- ↑ Bockarie, Moses; Hoerauf, Achim; Taylor, Mark J. (8 October 2010). "Lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis". The Lancet. 376 (9747): 1178.

- ↑ Taylor MJ, Makunde WH, McGarry HF, Turner JD, Mand S, Hoerauf A (2005), "Macrofilaricidal activity after doxycycline treatment of Wuchereria bancrofti: a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial", Lancet, 365 (9477): 2116–21, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66591-9, PMID 15964448

- ↑ Jan Andersson; Hans Forssberg; Juleen R. Zierath; The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet (5 October 2015), Avermectin and Artemisinin - Revolutionary Therapies against Parasitic Diseases (PDF), retrieved 5 October 2015

- ↑ Pringle, Heather (3 March 2011), The Emperor and the Parasite, retrieved 9 March 2011

Further reading

- "Special issue", Indian Journal of Urology, 21 (1), 2005

- "Filariasis". Therapeutics in Dermatology. June 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Filariasis. |

- Filariasis Research at the University of Tuebingen

- The Carter Center Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination Program

- UK Health Charity working to cure and prevent Lymphatic filariasis

- Brugia malayi Filarial worms. Video by R. Rao. Washington University in St. Louis

- Page from the "Merck Veterinary Manual" on "Parafilaria multipapillosa" in horses