Belz

| Belz Белз | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

|

Belz cityhall | |||

| |||

Belz Location within Lviv Oblast | |||

| Coordinates: UA 50°23′N 24°01′E / 50.38°N 24.02°E | |||

| Country | Ukraine | ||

| Province | Lviv Oblast | ||

| Named for | See in article | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Volodymyr Mukha | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 5.85 km2 (2.26 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 200 m (700 ft) | ||

| Population (2013) | |||

| • Total | 2,343 | ||

| • Density | 403,25/km2 (104,440/sq mi) | ||

| Zip Code | 80065 | ||

| Area code(s) | +380 3257 | ||

Belz (Ukrainian: Белз; Polish: Bełz; Yiddish: בעלז Belz), a small city in Sokal Raion of Lviv Oblast (region) of Western Ukraine, near the border with Poland, is located between the Solokiya river (a tributary of the Bug River) and the Rzeczyca stream. Prior to 15 February 1951 the town was located in central-eastern Poland, in the Lublin Voivodeship. Population: 2,343 (2013 est.)[1].

Origin of name

There are a few theories as to the origin of the name:

- Celtic language – belz (water) or pelz (stream),

- German language – Pelz/Belz (fur, furry)

- Old Slavic language and the Boyko language – «белз» or «бевз» (muddy place),

- Old East Slavic – «бълизь» (white place, a glade in the midst of dark woods).

The name occurs only in two other places, the first being a Celtic area in antiquity, and the second one being derived from its Romanian name:

- Belz (department Morbihan), Brittany, France

- Bălţi (Бельцы/Beljcy, also known in Yiddish as Beltz), Moldova (Bessarabia)

History

Duchy of Poland until 981

Kievan Rus 981-1018

Duchy of Poland 1018-1025

![]() Kingdom of Poland 1025-1031

Kingdom of Poland 1025-1031

Kievan Rus 1031-1170

![]() Duchy of Belz 1170-1234

Duchy of Belz 1170-1234

![]() Principality of Galicia–Volhynia 1234-1340

Principality of Galicia–Volhynia 1234-1340

![]() Grand Duchy of Lithuania 1340-1366

Grand Duchy of Lithuania 1340-1366

![]() Kingdom of Poland 1366-1377

Kingdom of Poland 1366-1377

![]() Kingdom of Hungary 1378-1387

Kingdom of Hungary 1378-1387

![]() Kingdom of Poland 1387-1569

Kingdom of Poland 1387-1569

![]() Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth 1569-1772

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth 1569-1772

![]() Habsburg Monarchy 1772-1804

Habsburg Monarchy 1772-1804

![]() Austrian Empire 1804-1867

Austrian Empire 1804-1867

![]() Austria-Hungary 1867-1918

Austria-Hungary 1867-1918

![]() West Ukrainian People's Republic 1918-1919

West Ukrainian People's Republic 1918-1919

![]() Second Polish Republic 1919-1939

Second Polish Republic 1919-1939

![]() Nazi Germany 1939-1944

Nazi Germany 1939-1944

![]() Polish People's Republic 1944-1951

Polish People's Republic 1944-1951

![]() Soviet Union 1951-1991

Soviet Union 1951-1991

![]() Ukraine 1991-present

Ukraine 1991-present

Early history

Belz is situated in a fertile plain which tribes of Indo-European origin settled in ancient times: Celtic Lugii,[2][3] next (2nd-5th century) German Goths,[4][5] slavized Sarmatians (White Croats),[6] and at last Slavic Lendians.[7]

The town has existed since at least the 10th century, as one of the Burgs of Czerwień[8] (Red Ruthenia) strongholds under Bohemian and Polish rule. In 981, Belz was incorporated into the Kievan Rus'.[9] In 1170 the town became a seat of the Duchy of Belz. In 1234 it was incorporated into the Duchy of Galicia–Volhynia, which would control Belz until 1340, when it came under Lithuanian rule.

Beltz was under Polish rule from 1366 to 1772, first as a fief then, from 1462 as part of the Kingdom of Poland. On October 5, 1377, the town was granted rights under the Magdeburg law by Władysław Opolczyk, Duke of Opole, then the Governor of Red Ruthenia. A charter, dated November 10, 1509, once again granted Belz privileges under the Magdeburg rights.[10]

In 1772, Belz was incorporated into the Habsburg Empire later (later the Austrian Empire and Austro-Hungarian Empire) where it was a part of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.

Modern history

With the collapse of Austria-Hungary following World War I in November 1918, Belz was included in the Western Ukrainian People's Republic. It came under Polish control in 1919 during the Polish-Ukrainian War. In April 1920, the Second Polish Republic, represented by Józef Piłsudski, and the Ukrainian People's Republic, represented by Symon Petlura signed the Treaty of Warsaw, in which they agreed that the Polish-Ukrainian border in Western Ukraine would follow the Zbruch River. This left Belz, along with the rest of Eastern Galicia in the Polish Republic.[11]

From 1919 to 1939 Belz was annexed to the Lviv Voivodeship, Second Polish Republic.

From 1939 to 1944 Belz was occupied by Germany as a part of the General Government. Belz is situated on left, north waterside of the Solokiya river (affluent of the Bug river), which was the German-Soviet border in 1939–1941.

After the war Belz reverted to Poland (where it was again within the Lublin Voivodeship) until 1951 when, after a border readjustment, it passed to the Soviet Union (Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic). (See: 1951 Polish–Soviet territorial exchange) Since 1991 it has been part of independent Ukraine.

Jewish history

The Karaites, believers in a literalist offshoot of Judaism (Karaite Judaism or Karaism, Hebrew: יהדות קראית), settled in Belz at the end of the 10th century, following the fall of the Khazar Khaganate.[12]

The Ashkenazi Jewish community in Belz was established circa 14th century. In 1665, the Jews in Belz received equal rights and duties.[13] The town became home to a Hasidic dynasty in the early 19th century.[14][15] At that time, the Rav of Belz, Rabbi Shalom Rokeach (1779–1855), also known as the Sar Shalom, joined the Hasidic movement by studying with the Maggid of Lutzk,[16] and was sent by him to Belz to establish the community and become the first Belzer Rebbe from 1817 to 1855.

A great Torah scholar, Rabbi Shalom Rokeach personally helped build the city's large and imposing synagogue, dedicated in 1843, which could seat 5,000 worshippers and had superb acoustics. When Rabbi Shalom died in 1855, his youngest son, Rabbi Yehoshua Rokeach (1855–1894), became the next Rebbe. Belzer Hasidism grew in size during Rebbe Yehoshua's tenure and the tenure of his son and successor, Rabbi Yissachar Dov Rokeach (1894–1926). Rabbi Yissachar Dov's son and successor, Rabbi Aharon Rokeach, escaped from Nazi-occupied Europe to Israel in 1944, re-establishing the Hasidut first in Tel Aviv and then in Jerusalem.

At the beginning of World War I, Belz had 6100 inhabitants, including 3600 Jews, 1600 Ukrainians, and 900 Poles.[17] During the German and Soviet invasion of Poland (September 1939), most of the Jews of Belz fled to the Soviet Union in Autumn 1939 (the German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation). However, by May 1942, there were over 1,540 local Jewish residents and refugees in Belz. On June 2, 1942, 1,000 Jews were deported to Hrubieszów and from there to the Sobibór extermination camp. Another 504 were brought to Hrubieszów in September of that year, after they were no longer needed to work on the farms in the area.[18]

Cultural trivia

The Yiddish song “Beltz, Mayn Shtetele” is a moving evocation of a happy childhood spent in a shtetl. Originally this song was composed for a town which bears a similar-sounding name in Yiddish (belts), called Bălţi in Moldovan/Romanian, and is located in Bessarabia[19] (presently the Moldova Republic). Later interpretations may have had Belz in mind, though. The song has special significance in Holocaust history, as a 16-year-old playing the song was overheard by an SS guard at Auschwitz extermination camp, who then forced the child to play it repeatedly to ease the moods of Jews being herded into the gas chambers.[20]

Belz is also a very important place for Ukrainian Catholics and Polish Catholics as a place where the Black Madonna of Częstochowa (this icon was believed to have painted by St. Luke the Evangelist) had resided for several centuries until 1382, when Władysław Opolczyk, duke of Opole, took the icon home to his principality after ending his service as the Royal emissary for Halychyna for Louis I of Hungary.[21]

Literature – Belles-lettres: a poem Maria: A Tale of the Ukraine written by Antoni Malczewski, and a novel Starościna Bełska: opowiadanie historyczne 1770–1774 by Józef Ignacy Kraszewski.

Notable residents

- Vsevolod Mstyslavych of Volhynia, prince of Belz (1170–1196)

- Vasylko Romanovych, prince of Belz (1207–1211)

- Alexander Vsevolodovych, prince of Belz (1212–1234)

- Daniel of Galicia, prince of Belz (1234–1245)

- Lev I of Galicia, prince of Belz (1245–1264)

- Yuri I of Galicia, prince of Belz (1264–1301)

- Andrew of Galicia, prince of Belz (1308–1323)

- Boleslaw-Yuri II of Galicia, Polish-Lithuanian-Ruthenian prince of Belz (1323–1340)

- Yuri Narimuntovich (Jurgis Narimantaitis), Lithuanian, prince of Belz (1340–1377)

- Władysław Opolczyk, Silesian duke, Hungarian governor (1377–1378)

- Siemowit IV, Duke of Masovia, prince of Belz (1388–1426)

- Jaśko Mazowita, prefect of Belz (14th–15th centuries)

- Casimir II of Belz, prince of Belz (1434–1442)

- Jan Kamieniecki (1463–1513), starost of Belz

- Mikołaj Sieniawski (c. 1489–1569), voivode of Belz

- Jan Firlej (c. 1521–1574), voivode of Belz

- Jan Zamoyski (1542–1605), starost of Belz

- Yoel Sirkis (1561–1640), great Rabbi, one of Achronim

- Rafał Leszczyński (1579–1636), voivode of Belz

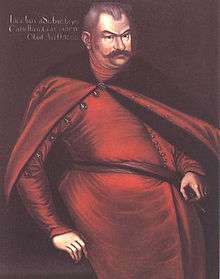

- Jakub Sobieski (1580–1646), voivode of Belz

- Dymitr Jerzy Wiśniowiecki (1631–1682), voivode of Belz

- Marcin Zamoyski (c.1637–1689), starost of Belz

- Stefan Aleksander Potocki, voivode of Belz

- Adam Mikołaj Sieniawski (1666–1726), voivode of Belz

- Stanisław Mateusz Rzewuski (1642–1728), voivode of Belz

- Stanisław Szczęsny Potocki (1753–1805), starost of Belz

- Sholom Rokeach (1779–1855), the first Rebbe of Belz

- Malka Rokeach (1780–1853), the first rebbetzin of Belz

- Nissan Spivak (1824–1906), cantor[22]

- Yehoshua Rokeach (1825–1894), the second Rebbe of Belz

- Yissachar Dov Rokeach (1854–1926), the third Rebbe of Belz

- Aharon Rokeach (1877–1957), the fourth Rebbe of Belz

- Peter Jacob Frostig (1896–1959), psychiatrist

- Mordechai Rokeach (1902–1949), son of Yissachar Dov Rokeach, the third Belzer Rebbe, and father of Yissachar Dov Rokeach, the fifth Belzer Rebbe

See also

References

- ↑ "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ Gaius Cornelius Tacitus, De Origine et situ Germanorum

- ↑ http://www.arts.ulster.ac.uk/lanlit/celto-slavica/abstracts.html[] Alexander Falileyev, Celto-Slavica. University of Ulster, 2004

- ↑ http://www.pan-ol.lublin.pl/biul_5/art_505.htm Hrubieszowskie w dobie panowania Gotów

- ↑ Andrzej Kokowski, Archeologia Gotów. Goci w Kotlinie Hrubieszowskiej, Lublin 1999

- ↑ Kazimierz Godłowski, Z badań nad rozprzestrzenieniem się Słowian w V-VII w. n.e., Kraków 1979

- ↑ Magdalena Mączyńska, Wędrówki Ludów. Kraków 1996

- ↑ http://wyborcza.pl/1,75476,8601329,Nazywam_sie_Czerwien.html

- ↑ Artur Pawłowski, Roztocze, Oficyna Wydawnicza "Rewasz", Warszawa 2009. ISBN 978-83-89188-87-8

- ↑ Yehorova, Iryna. "Belz is 1,000 years old".

- ↑ Richard K Debo, Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918–1921, pp. 210-211, McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, ISBN 0-7735-0828-7.

- ↑ Cmentarze żydowskie; Bełz – Ukraina

- ↑ Dr Fryderyk Papée, Zabytki przeszłości miasta Bełza. Lwów 1884

- ↑ Rabinowicz, Rabbi Tsvi (1989). "Chassidic Rebbes: From the Baal Shem Tov to Modern Times". Targum Press.

- ↑ Yodlov, Yitshak Shlomo. "Sefer Yikhus Belz (The Lineage Book of the Grand Rabbis of Belz)".

- ↑ Preface to the Divras Shlomo signed by the Belzer Rebbe, 1997

- ↑ Dr Mieczysław Orłowicz. Ilustrowany Przewodnik po Galicyi. Lwów 1919.

- ↑ Spector, Shmuel and Wigoder, Geoffrey, The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust, p. 105. NY:NYU Press 2001.

- ↑ Ami Living (87): 45. Sep 12, 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ BBC Magazine

- ↑ The Black Madonna Archived January 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Personality of the Week – Spivak Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Belz. |

- (Polish) Bełz (Belz) in the Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland (1880)

- Google location

- Blog for people who are researching ancestors in Belz

Coordinates: 50°22′N 24°00′E / 50.367°N 24.000°E