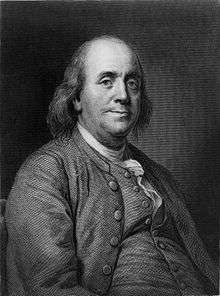

Ben Franklin effect

The Ben Franklin effect is a proposed psychological phenomenon: A person who has performed a favor for someone is more likely to do another favor for that person than they would be if they had received a favor from that person. An explanation for this would be that we internalize the reason that we helped them was because we liked them. The opposite case is also believed to be true, namely that we come to hate a person whom we did wrong to. We de-humanize them to justify the bad things we did to them.[1]

Recognition of effect by Franklin

Benjamin Franklin, for whom the effect is named, quotes what he describes as an "old maxim" in his autobiography: "He that has once done you a kindness will be more ready to do you another, than he whom you yourself have obliged."[2]

In his autobiography, Franklin explains how he dealt with the animosity of a rival legislator when he served in the Pennsylvania legislature in the 18th century:

Having heard that he had in his library a certain very scarce and curious book, I wrote a note to him, expressing my desire of perusing that book, and requesting he would do me the favour of lending it to me for a few days. He sent it immediately, and I return'd it in about a week with another note, expressing strongly my sense of the favour. When we next met in the House, he spoke to me (which he had never done before), and with great civility; and he ever after manifested a readiness to serve me on all occasions, so that we became great friends, and our friendship continued to his death.

Effect as an example of cognitive dissonance

This perception of Franklin has been cited as an example within cognitive dissonance theory, which says that people change their attitudes or behavior to resolve tensions, or "dissonance," between their thoughts, attitudes, and actions. In the case of the Ben Franklin effect, the dissonance is between the subject's negative attitudes to the other person and the knowledge that they did that person a favor.[3][4]

See also

Notes

- ↑ A more detailed explanation appears at the page on the Ben Franklin effect at changingminds.org.

- ↑ From The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, page 48 Archived January 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Paul Henry Mussen, Mark R. Rosenzweig & Arthur L. Blumenthal (1979). Psychology: an introduction, p.403. University of Michigan. ISBN 0-669-01672-1

- ↑ Tavris, Carol; Elliot Aronson (2008). Mistakes were made (but not by me). Pinter and Martin. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-1-905177-21-9.

Further reading

- Jecker, John; David Landy (1969). "Liking a Person as a Function of Doing Him a Favor". Human Relations. 22 (4): 371–378. doi:10.1177/001872676902200407.

- Schopler, John; Compere, John S. (1971). "Effects of being kind or harsh to another on liking.". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 20 (2): 155–159. doi:10.1037/h0031689. ISSN 0022-3514.

- The Ben Franklin Effect: An Unexpected Way to Build Rapport: http://buildthefire.com/ben-franklin-effect/