Billing (filmmaking)

Billing is a performing arts term used in referring to the order and other aspects of how credits are presented for plays, films, television, or other creative works. Information given in billing usually consists of the companies, actors, directors, producers, and other crew members. This article examines billing for theatrical films.

Films

From the beginning of motion pictures in the 1900s to the early 1920s, the moguls that owned or managed big film studios did not want to bill the actors appearing in their films because they did not want to recreate the star system that was prevalent on Broadway at that time. They also feared that, once actors were billed on film, they would be more popular and would seek large salaries. Actors themselves did not want to reveal their film careers to their stage counterparts via billing on film, because at that time working in the movies was unacceptable to stage actors. As late as the 1910s, stars as famous as Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin were not known by name to moviegoers. According to Mary Pickford's biography Doug and Mary,[1] she was referred to by the public as "the Biograph girl" in all of her films before 1905.

Before Mary Pickford, the public used to call Florence Lawrence the "Biograph girl". In 1910 Lawrence was lured away from Biograph by Carl Laemmle when he started the Independent Motion Picture Company (IMP). Laemmle wanted Lawrence to be his star attraction, so he offered her more money ($250 per week) and marquee billing, something Biograph did not allow. She signed on; with the release of her first IMP film, The Broken Oath, she became the first film star to receive billing on the credits of her film. From then on, actors received billing on film. Also originating during that time was the system of billing above and below the title, to delineate the status of the players. Big stars such as Pickford, Fairbanks, and Chaplin were billed above the title, while lesser stars and supporting players were billed below the title.

During the era of the studio system, on-screen billing was presented at the beginning of a film; only a restatement of the cast and possibly additional players appeared at the end, because the studios had actors under contract and could decide billing. The studios still followed the billing system of the silent era.

After the studio system's collapse in the 1950s, actors and their agents fought for billing on a film-by-film basis. This, combined with changes in union contracts and copyright laws, led to more actors and crew members being included in the credits sequence, expanding its size significantly. As a result, since the late 1960s, a significant amount of the billing is reserved for the closing credits of the film, which generally includes a recap of the billing shown at the beginning. In addition, more stars began to demand top billing.

Billing demands even extended to publicity materials, down to the height of the letters and the position of names.

By the 1990s, some films had moved all billing to the film's end, with the exception of company logos and the title. Although popularised by the Star Wars series (see below) and used sporadically in films such as The Godfather and Ghostbusters, this "title-only" billing became an established form for summer blockbusters in 1989, with Ghostbusters II, Lethal Weapon 2, and The Abyss following the practice.[2] Occasionally, even the title is left to the end, such as in Avatar, The Passion of the Christ, Inception, and the "Dark Knight" trilogy.

Main billing

The order in which credits are billed generally signify their importance. For example, in films, the first is usually the motion picture company, followed by the producer (as in "A Jerry Bruckheimer Production"). Next, depending on his/her standing, the director may be granted an extra, prominent credit (as in "A Ridley Scott Film"); this practice began with directors such as Otto Preminger, David Lean and John Frankenheimer in the mid-1960s.

The major starring actors generally come next, then the title of the movie and the rest of the principal cast. If their contribution is deemed significant, other personnel (such as visual effects supervisor) may also be included. These are then followed by the other producers, the screenwriter(s) and again the director (as in "Directed by..."). If the main credits occur at the beginning, then the director's name is last to be shown before the film's narrative starts, as a result of an agreement between the DGA and motion picture producers in 1939. However, if all billing is shown at the end, his/her name will be displayed first, immediately followed by the writing credits.

Up until the establishment of the director's possessive credit, e.g. "A George Roy Hill Film" in the early 1970s, some directors were so highly regarded that they received what seems to be a producer's credit, even if they did not produce the film. Victor Fleming was one such director: his films usually featured the credit "A Victor Fleming Production", even when someone else produced the film. James Whale was similarly credited.[3]

Since 1990, it has become common to put all the filmmaking and cast credits at the end of the film, usually in this order:

- Director

- Screenwriter(s)

- Producer(s)

- Executive Producer(s)

- Director of Photography

- Production Designer

- Film Editor

- Composer

- Costume Designer

- Visual Effects Supervisor

- Casting director(s)

- Main Cast

- Motion picture/production companies

(generally in reverse order for opening billings)

The actors whose names appear first are said to have "top billing". They usually play the principal characters in the film and have the most screen time. However, well-known actors may be given top billing for publicity or contractual purposes if juvenile, lesser-known, or first-time performers appear in a larger role: e.g., Marlon Brando and Gene Hackman were both credited before the title in Superman (1978), while Christopher Reeve, the then-unknown actor who played Superman, was not. Frequently, top-billed actors are also named in advertising material such as trailers, posters, billboards and TV spots.

An actor may receive "last billing", which usually designates a smaller role played by a famous name. They are usually credited after the rest of the lead cast, prefixed with "and" (or also "with" if there is more than one, as Samuel L. Jackson was in the latter two Star Wars prequels). In some cases, the name is followed by "as" and then the name of the character (sometimes called an "and-as" credit). This is not the case if that character is unseen for most of the movie (see Ernst Stavro Blofeld).

An early last billing credit in a film's opening simply listed a question mark (?) as portraying the monster in the 1931 classic Frankenstein, which still lists it that way today, although the reissued prints seen today add actor Boris Karloff to the end credit listings, as the film made him a huge star such that the credits of the film's first sequel The Bride of Frankenstein credits him only by his last name.

One of the first "and-as" credits was afforded Spencer Tracy (as Lieutenant Colonel James H. Doolittle) in the 1944 World War II film Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, since another top box office star of the time, Van Johnson, had top billing and Tracy was too big a star to receive second billing.

Some films have both an "and-as" credit and a separate last billing credit, such as the Irwin Allen 1978 disaster film The Swarm, the opening credits of which, after listing an already large cast of stars, concludes with "Fred MacMurray as Clarence ... and Henry Fonda".

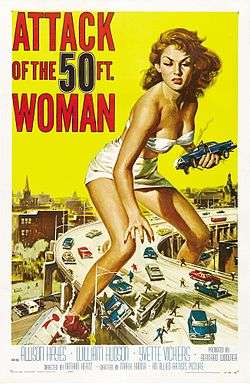

The two or three top-billed actors in a movie will usually be announced prior to the title of the movie; this is referred to as "above-title billing". For an actor to receive it, he/she will generally have to be well-established, with box-office drawing power. Those introduced afterward are generally considered to be the supporting cast.

Actors that have high status in the industry do not always get top billing; if they only play a bit part, then it may go to the person who portrayed the main character. Some major actors may have a cameo, where they are only noted within the other cast during the end credits. Sometimes, top billing will be given based on a person's level of fame. For example, besides his brief appearance in Superman, Marlon Brando received top billing in both The Godfather and Apocalypse Now.

If an unfamiliar actor has the lead role, he may be listed last in the list of principal supporting actors, his name prefixed with "and introducing" (as Peter O'Toole was in Lawrence of Arabia) However "and introducing" is now mostly used in feature films by a young actor (usually a child) who appears for the first time in a motion picture. Sometimes, he may not receive special billing even if his role is crucial. For example, the then-unknown William Warfield, who played Joe and sang "Ol' Man River" in the 1951 film version of Show Boat, received tenth billing as if he were merely a bit player, while Paul Robeson, an established star who played the same role in the 1936 film version of the musical, received fourth billing in the 1936 film.

If more than one name appears at the same time or of a similar size, then those actors are said to have "equal billing," with their importance decreasing from left to right. However, an instance of "equal importance" is The Towering Inferno (1974) starring Steve McQueen and Paul Newman. The two names appear simultaneously with Newman's on the right side of the screen and raised slightly higher than McQueen's, to indicate the comparable status of both actors' characters (this also features on the advertising poster).

If a film has an ensemble cast with no clear lead role, it is traditional to bill the participants alphabetically or in the order of their on-screen appearance. An example of the former is A Bridge Too Far (1977), which featured 14 roles played by established stars, any one of whom would have ordinarily received top billing as an individual. The cast of the Harry Potter films includes many recognized stars who are billed alphabetically, but after the three principals.

In the case of the Kenneth Branagh Hamlet, there were many famous actors playing supporting or bit roles, and these actors were given prominent billing in the posters along with the film's actual stars: Branagh, Derek Jacobi, Julie Christie, and Kate Winslet. In the actual film's credits, they (along with the other actors in the film) were listed in alphabetical order and in the same size typeface.

If an actor is not an established star, he or she may not receive above-the-title billing, or even "star" billing; they may just be listed at the head of the cast. This is the way that all of the actors were listed in the opening credits to The Wizard of Oz; Judy Garland, although listed first, was given equal billing to all the others, with the cast list reading "with Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Jack Haley," etc. F. Murray Abraham, a supporting actor at the time of Amadeus, did not receive special star billing although he played the lead role of Antonio Salieri; his onscreen credit reads "with F. Murray Abraham", although his name does appear first in the cast.

In some cases, the position of a name in the credits roll can become a sticking point for both cast and crew. Such was the case on the sixties TV sitcom Gilligan's Island, where two of the stars were only mentioned by name in the closing credits. In fact, the characters of The Professor (Russell Johnson) and Mary Ann (Dawn Wells) were the only ones whose mention in the opening theme song was abbreviated simply as "the rest" in the show's first season. Bob Denver, who played Gilligan, was so upset with this treatment that he reportedly told the producers that since his contract stipulated that his name could appear anywhere in the credits that he wished, he wanted to be moved to the end credits with his co-stars. From the show's second season, the studio capitulated, and moved Denver's co-stars to the opening credits of the show, and also changed the theme song's lyrics to include "The Professor and Mary Ann" instead of saying "and the rest".

Competitive top billing

Sometimes actors can become highly competitive over the order of billing. For example:

Spencer Tracy was originally cast to play the lead opposite Humphrey Bogart in The Desperate Hours (1955) but when neither actor would relinquish top billing, Tracy withdrew and was replaced by Fredric March, who took second billing to Bogart. Bogart's role in the film had earlier been played on Broadway by Paul Newman but the young actor was not considered for the movie version since Newman, viewed by studios at the time as mainly a stage and television actor only beginning his movie career, was in no position to compete with Bogart.

Spencer Tracy would also later back out of co-starring in the 1965 film The Cincinnati Kid when he learned he would have to take second billing behind the film's star Steve McQueen. The role Tracy had been cast in went instead to Edward G. Robinson, whom McQueen had idolized from childhood.

Whenever it was pointed out to Spencer Tracy that he routinely took top billing in his films with Katharine Hepburn, he responded, "It's a movie, not a lifeboat."

Clark Gable had a top billing clause written into his MGM contract and made three major films in the 1930s with Spencer Tracy in supporting roles (San Francisco, Test Pilot, and Boom Town), but when Tracy renegotiated his contract during World War II, he had the same clause included in his own contract, effectively ending the hugely popular Gable-Tracy team.

In the opening credits of The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), Alec Guinness, who is generally regarded as the main character in the film, receives third billing, after William Holden (who demanded top billing) and Jack Hawkins (who does not even appear until halfway through the picture). However, in the closing credits, Guinness is billed second with Hawkins third.

For The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), James Stewart was given top billing over John Wayne in the movie's posters and the previews (trailers) shown in cinemas and on television prior to the film's release, but in the film itself, Wayne is accorded top billing. Their names are displayed on pictures of signposts, one after the other, with Wayne's name shown first with his sign mounted slightly higher on its post than Stewart's. Director John Ford remarked in an interview with Peter Bogdanovich that he made it apparent to the audience that Vera Miles' character had never entirely recovered from an abortive romance with Wayne's gunslinging rancher because "I wanted Wayne to be the lead."[4] Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford used precisely the same billing formula for All the President's Men (1976), with Redford receiving top billing in posters and trailers while Hoffman was billed over Redford in the film itself.[5]

As both Tony Curtis and Jerry Lewis wanted top billing for Boeing Boeing (1965), their animated names appeared in a spinning, circular fashion in front of an airplane engine's rotating nacelle.[6] For the trailer, the circular animation of the two names was repeated and neither name was spoken aloud. For the posters, the names made an X, Lewis' going up from the bottom left and Curtis' going down from the upper left.

For the film The Towering Inferno (1974), Steve McQueen, Paul Newman and William Holden all tried to obtain top billing. Holden was refused as his diminished star power was no longer considered to be in the league of McQueen's and Newman's. To provide dual top billing and mollify McQueen, the credits were arranged diagonally, with McQueen at the lower left and Newman at the upper right. Thus, each actor appeared to have top billing depending on whether the poster was read from left to right or top to bottom.[7] Technically, McQueen has top billing and is mentioned first in the film's trailers; however, at the end of the movie, as the cast's names roll from the bottom of the screen, Newman's name is fully visible first, giving him top billing in the closing credits. This was the first time that this type of "staggered but equal" billing had been used for a movie, although the same thing had been discussed for the same two actors five years earlier when McQueen was going to play the Sundance Kid in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). McQueen ultimately passed on the part and was replaced by Robert Redford, who did not enjoy McQueen's status and took second billing to Newman. Today, it has become understood that whoever's name appears to the left has top billing, but this was by no means the case when The Towering Inferno was produced. This same approach has often been used subsequently, including 2008's Righteous Kill starring Robert De Niro and Al Pacino.[8]

In The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), F. Murray Abraham asked for above-title billing. This was rejected as too many other stars were getting it (Tom Hanks, Bruce Willis, Melanie Griffith). Thus, Abraham asked for his name to be completely removed, even from the closing credits. That same year, Raúl Juliá requested above the title billing alongside Robert Redford and Lena Olin for the drama Havana. When the producers rejected this, he decided to go uncredited. Eleven years later, Don Cheadle did exactly the same thing when his name wasn't allowed to appear above the title in Ocean's Eleven (2001), presumably because his name would have alphabetically preceded George Clooney's and, unlike with the later sequels, the cast above the title was presented alphabetically (Clooney, Matt Damon, Andy García, Brad Pitt, and Julia Roberts). Cheadle removed his name from the credits.[9] The producers apparently wanted Clooney, not Cheadle, to be the first name a casual viewer of the advertising would see.

In the film Miami Vice (2006), Colin Farrell originally received top billing. However, after Jamie Foxx won an Academy Award he requested top billing and received it despite his role actually being much smaller than Farrell's. Foxx's name appears first in the opening credits, while Farrell still receives top billing in the closing credits.

In a commercial for Michael and Michael Have Issues (2009), the aforementioned characters mock-argue over who gets top billing for their show.

Director billing

- In 1980, George Lucas resigned from the Directors Guild of America after it insisted, against his wishes, that Irvin Kershner, the director of The Empire Strikes Back, be credited at the beginning of the film because the company name Lucasfilm was there; it had previously allowed the original Star Wars (1977), which had a similar opening sequence, to go unchallenged because the writer-director credit (George Lucas) matched the company name Lucasfilm Ltd.

- Kevin Smith's films do not use the possessory credit "A Kevin Smith Film". His feeling is that a movie is made by everyone involved, and not the product of just the director.[10]

- Ben-Hur is one of the few MGM films in which the director receives very prominent billing in the posters advertising the movie – the posters state "William Wyler's Production of", although the same credit does not appear in the actual on-screen credits.[11] A similar example is David Lean, whose Doctor Zhivago and Ryan's Daughter both carry the credit "David Lean's Film of" (followed by the title). Stanley Kubrick received prominent title billing from Dr. Strangelove (1964) onwards, and from A Clockwork Orange (1971) he generally received main billing, with the actors only listed in the billing block. Advertising materials for Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut featured the billing "CRUISE / KIDMAN / KUBRICK."

- Filmmaker and playwright Tyler Perry always inserts his name into the title of each of his films and television shows. For instance: Tyler Perry's Why Did I Get Married? or Tyler Perry's Meet the Browns. To date, the only film he has not done this with is For Colored Girls, which is an adaptation of the Ntozake Shange play For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf.

Unbilled appearances

- As Gary Oldman appeared under heavy make-up in Hannibal, he requested that his name be completely removed from the billing and credits in order to "do it anonymously".[12] However, Nathan Murray is still credited as "Mr. Oldman's assistant" and Oldman's name was added to the end credits upon the film's home video release.

- For suspense purposes, Kevin Spacey, in Seven, requested not to be credited in the opening titles or in any advertising for the film.[13] His name appears in the closing credits.

- In the opening of 1931's Frankenstein, the credit for "The Monster" is a question mark. Boris Karloff is named in the closing credits.

- Ashton Kutcher appears as the main antagonist, Hank, in the 2003 family comedy Cheaper by the Dozen and is uncredited although he is one of the film's main characters.

- In the 1974 film Earthquake, Walter Matthau agreed to provide a cameo performance without compensation on the condition that he not be credited under his real name; he was credited under a fictitious name of his choosing, "Walter Matuschanskayasky."

- Because he played the part without pay, Bruce Willis is not credited for his prominent role in the portion of Four Rooms directed by Quentin Tarantino.

- Owen Wilson does not receive credit for his "Jedidiah" character in Night at the Museum, though he receives credit in the sequel, Battle of the Smithsonian.

- John Wayne was billed as "Michael Morris" in two cameo television appearances directed by John Ford, an episode of Wagon Train and an anthology installment called Flashing Spikes starring James Stewart. Wayne's real name was Marion Michael Morrison.

- For his cameo appearances in Cabin Boy and Beavis and Butt-head Do America, David Letterman was billed as "Earl Hofert."

Other unbilled roles feature famous actors or actresses who pop up in a movie as a face in a crowd, a man on a bench, or other 'background' characters, who are given screen time for a brief, but recognizable, moment, such as Bing Crosby and Bob Hope momentarily appearing in a circus audience during The Greatest Show on Earth. They can be recognized, but sometimes are not credited for financial reasons – if they receive credit, they would be due payment commensurate with their fame.

Billing block

The "billing block" is the "list of names that adorn the bottom portion of the official poster (or 'one sheet', as it is called in the movie industry) of the movie".[14] In the layout of film posters and other film advertising copy, the billing block is usually set in a highly condensed typeface (one in which the height of characters is several times the width).[15]

By convention, the point size of the billing block is 15 to 35 percent of the average height of each letter in the title logo.[16] Inclusion in the credits and the billing block is generally a matter of detailed contracts between Hollywood labor unions representing creative talent and the producer or film distributor. The labor union contracts specify minimum requirements for presenting actors, writers and directors.[17] But star talent is free to individually negotiate larger name presentations, such as when a star actor or director has his or her name above a movie’s title. The union contracts also cover billing blocks in trailers, outdoor billboards, TV commercials, newspaper advertising and online advertising. Using a condensed typeface allows the heights of the characters to meet contractual constraints while still allowing enough horizontal space to include all the required text.[18]

See also

- Acknowledgment (creative arts)

- Alan Smithee, pseudonym used by directors who do not want their name associated with the final project.

- Closing credits

- Credit (creative arts)

- Opening credits

- Possessory credit

- Title sequence

- WGA screenwriting credit system

References

Specific references:

- ↑ Doug & Mary: A biography of Douglas Fairbanks & Mary Pickford, by Gary Carey, E.P. Dutton, 1977, ISBN 978-0-525-09512-5

- ↑ Keyword 'no opening credits' from IMDb

- ↑

- ↑ Who The Devil Made It: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors by Peter Bogdanovich

- ↑

- ↑ Private Screenings: Tony Curtis. Turner Classic Movies, 19 Jan 1999.

- ↑ The Towering Inferno Masterprint at Art.com

- ↑ http://www.impawards.com/2008/righteous_kill.html

- ↑ http://www.impawards.com/2001/oceans_eleven_ver2.html

- ↑ Enhanced Playback Trivia Track (2004). Clerks. X Tenth Anniversary Edition (DVD). Buena Vista Home Entertainment.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4Vqh-dOq04&feature=related

- ↑ Interview with Gary Oldman from IGN

- ↑ Seven Trivia – IMDb

- ↑ Crabb, Kelly (2005). The Movie Business: The Definitive Guide to the Legal and Financial Secrets of Getting Your Movie Made. Simon and Schuster. p. 72. ISBN 9780743264921.

- ↑ "Credit Where Credit is Due". Posterwire.com. March 21, 2005. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- ↑ Jaramillo, Brian (March 4, 2009). "Corey Holmes watches the Watchmen". Lettercult. Retrieved 2012-10-04.

- ↑ Marich, Robert (2013) Marketing To Moviegoers: Third Edition (2013), SIU Press, p. 18-20

- ↑ Schott, Ben (February 23, 2013). "Assembling the Billing Block". The New York Times.

General references:

- Robert Glatzer (October 1998). "Movie credits 101". Salon.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009.

- "Egos: Watch My Line". Time. January 5, 1962.