Paul Newman

| Paul Newman | |

|---|---|

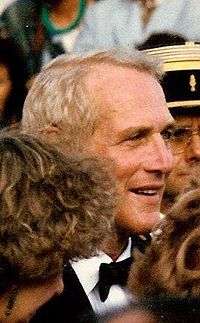

Newman in 1963 | |

| Born |

Paul Leonard Newman January 26, 1925 Shaker Heights, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died |

September 26, 2008 (aged 83) Westport, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Lung cancer |

| Alma mater | Kenyon College, B.A. 1949 |

| Occupation | Actor, director, entrepreneur, professional racing driver, philanthropist |

| Years active | 1951–2008 |

| Spouse(s) |

Jackie Witte (m. 1949; div. 1958) Joanne Woodward (m. 1958; his death 2008) |

| Children | 6 (including Scott, Nell, and Melissa) |

Paul Leonard Newman (January 26, 1925 – September 26, 2008) was an American actor, film director, entrepreneur, professional race car driver and team owner, environmentalist, activist, and philanthropist. He won and was nominated for numerous awards, winning an Academy Award for his performance in the 1986 film The Color of Money,[1] a BAFTA Award, a Screen Actors Guild Award, a Cannes Film Festival Award, an Emmy Award, and many others. Newman's other films include The Hustler (1961), Cool Hand Luke (1967), as Butch Cassidy in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), The Sting (1973), and The Verdict (1982).

Despite being colorblind, Newman won several national championships as a driver in Sports Car Club of America road racing, and his race teams won several championships in open wheel IndyCar racing. He was a co-founder of Newman's Own, a food company from which he donated all post-tax profits and royalties to charity.[2] As of 2016, these donations have totaled over US$460 million.[3] He was also a co-founder of Safe Water Network, a nonprofit that develops sustainable drinking water solutions for those in need.[4] In 1988, Newman founded the SeriousFun Children's Network, a global family of summer camps and programs for children with serious illness which has served 290,076 children since its inception.[5]

Early life

Newman was born in Shaker Heights, Ohio, the second son of Theresa (née Fetzer, Fetzko, or Fetsko; Slovak: Terézia Fecková;[6][7] died 1982) and Arthur Sigmund Newman (died 1950), who ran a profitable sporting goods store.[8][9][10] Newman's father was Jewish, and was the son of Simon Newman and Hannah Cohn, immigrants from Hungary and Poland.[9][11] His mother, Theresa, whose year of birth remains unclear but appears to have been between 1889 and 1895, was a practitioner of Christian Science, and was born to a Slovak Roman Catholic family in Homonna in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Humenné in the Republic of Slovakia).[7][12][13][14] Newman had no religion as an adult, but described himself as a Jew, saying "it's more of a challenge".[15] Newman's mother worked in his father's store, while raising Paul and his elder brother, Arthur,[16] who later became a producer and production manager.[17]

Newman showed an early interest in the theater; his first role was at the age of seven, playing the court jester in a school production of Robin Hood. At age 10, Newman performed at the Cleveland Play House in a production of Saint George and the Dragon, and was a notable actor and alumnus of their Curtain Pullers children's theatre program.[18] Graduating from Shaker Heights High School in 1943, he briefly attended Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, where he was initiated into the Phi Kappa Tau fraternity.[17]

Newman served in the United States Navy in World War II in the Pacific theater.[17] Initially, he enrolled in the Navy V-12 pilot training program at Yale University, but was dropped when his colorblindness was discovered.[17][19] Boot camp followed, with training as a radioman and rear gunner. Qualifying in torpedo bombers in 1944, Aviation Radioman Third Class Newman was sent to Barbers Point, Hawaii. He was subsequently assigned to Pacific-based replacement torpedo squadrons VT-98, VT-99, and VT-100, responsible primarily for training replacement combat pilots and air crewmen, with special emphasis on carrier landings.[19] He later flew as a turret gunner in an Avenger torpedo bomber. As a radioman-gunner, he was ordered aboard the USS Bunker Hill with a draft of replacements shortly before the Battle of Okinawa in the spring of 1945. His pilot's ear infection kept their plane grounded while the rest of their squadron continued to the aircraft carrier. Days later, the rest of their unit on the USS Bunker Hill were among those killed when the ship was the target of a kamikaze attack.[20][21]

After the war, Newman completed his Bachelor of Arts in drama and economics at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio in 1949.[22] Shortly after earning his degree, he joined several summer stock companies, most notably the Belfry Players in Wisconsin[23] and the Woodstock Players in Illinois. He toured with them for three months and developed his talents as a part of Woodstock Players.[17][24] He later attended the Yale School of Drama for one year, before moving to New York City to study under Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio.[17] Oscar Levant wrote that Newman initially was hesitant to leave New York for Hollywood, and that Newman had said, "Too close to the cake. Also, no place to study."[25]

Career

Early work and mainstream success

Newman arrived in New York City in 1951 with his first wife Jackie Witte, taking up residence in the St. George section of Staten Island.[26][27] He made his Broadway theatre debut in the original production of William Inge's Picnic with Kim Stanley in 1953 and appeared in the original Broadway production of The Desperate Hours in 1955. In 1959, he was in the original Broadway production of Sweet Bird of Youth with Geraldine Page and three years later starred with Page in the film version. During this time Newman started acting in television. His first credited role was in a 1952 episode of Tales of Tomorrow entitled "Ice from Space".[28] In the mid-1950s, he appeared twice on CBS's Appointment with Adventure anthology series.[29]

In February 1954, Newman appeared in a screen test with James Dean, directed by Gjon Mili, for East of Eden (1955). Newman was tested for the role of Aron Trask, Dean for the role of Aron's fraternal twin brother Cal. Dean won his part, but Newman lost out to Richard Davalos. That same year, he co-starred with Eva Marie Saint and Frank Sinatra in a live—and color—television broadcast of Our Town, a musical adaptation of Thornton Wilder's stage play. Newman was a last-minute replacement for James Dean.[30] The Dean connection had resonance two other times, as Newman was cast in two leading roles originally earmarked for Dean, as Billy the Kid in The Left Handed Gun and as Rocky Graziano in Somebody Up There Likes Me, both filmed after Dean's death in an automobile collision.[29]

Newman's first film for Hollywood was The Silver Chalice (1954). The film was a box office failure and the actor would later acknowledge his disdain for it.[31] In 1956, Newman garnered much attention and acclaim for the role of Rocky Graziano in Somebody Up There Likes Me. In 1958, he starred in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), opposite Elizabeth Taylor. The film was a box office smash and Newman garnered his first Academy Award nomination. Also in 1958, Newman starred in The Long, Hot Summer with Joanne Woodward, with whom he reconnected on the set in 1957 (they had first met in 1953). He won Best Actor at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival for this film.[29]

Major films

Newman starred in The Young Philadelphians (1959), Exodus (1960), The Hustler (1961), Hud (1963), Harper (1966), Hombre (1967), Cool Hand Luke (1967), The Towering Inferno (1974), Slap Shot (1977), and The Verdict (1982). He teamed with fellow actor Robert Redford and director George Roy Hill for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1973).[29] After his marriage to Woodward they appeared together in The Long, Hot Summer (1958), Rally 'Round the Flag, Boys!, (1958), From the Terrace (1960), Paris Blues (1961), A New Kind of Love (1963), Winning (1969), WUSA (1970), The Drowning Pool (1975), Harry & Son (1984), and Mr. and Mrs. Bridge (1990). They starred in the HBO miniseries Empire Falls, but did not share any scenes.[29]

In addition to starring in and directing Harry & Son, Newman directed four feature films starring Woodward. They were Rachel, Rachel (1968), based on Margaret Laurence's A Jest of God, the screen version of the Pulitzer Prize–winning play The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds (1972), the television screen version of the Pulitzer Prize–winning play The Shadow Box (1980), and a screen version of Tennessee Williams' The Glass Menagerie (1987). Twenty-five years after The Hustler, Newman reprised his role of "Fast Eddie" Felson in the Martin Scorsese–directed film The Color of Money (1986), for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor.

21st century roles

In 2003, Newman appeared in a Broadway revival of Wilder's Our Town, receiving his first Tony Award nomination for his performance. PBS and the cable network Showtime aired a taping of the production, and Newman was nominated for an Emmy Award[32] for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Miniseries or TV Movie.

Newman's last movie appearance was as a conflicted mob boss in the 2002 film Road to Perdition opposite Tom Hanks, for which he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. His last appearance overall, although he continued to provide voice work for films, was in 2005 in the HBO mini-series Empire Falls (based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Richard Russo) in which he played the dissolute father of the protagonist, Miles Roby and for which he won a Golden Globe and a Primetime Emmy. In 2006, in keeping with his strong interest in car racing, he provided the voice of Doc Hudson, a retired anthropomorphic race car in Disney/Pixar's Cars — this was his final role for a major feature film.

Newman retired from acting in May 2007, saying "You start to lose your memory, you start to lose your confidence, you start to lose your invention. So I think that's pretty much a closed book for me."[33] He came out of retirement to record narration for the 2007 documentary Dale, about the life of NASCAR driver Dale Earnhardt, and for the 2008 documentary The Meerkats.

Philanthropy

With writer A. E. Hotchner, Newman founded Newman's Own, a line of food products, in 1982. The brand started with salad dressing, and has expanded to include pasta sauce, lemonade, popcorn, salsa, and wine, among other things. Newman established a policy that all proceeds, after taxes, would be donated to charity. As of 2014, the franchise has donated in excess of $400 million.[2] He co-wrote a memoir about the subject with Hotchner, Shameless Exploitation in Pursuit of the Common Good. Among other awards, Newman's Own co-sponsors the PEN/Newman's Own First Amendment Award, a $25,000 reward designed to recognize those who protect the First Amendment as it applies to the written word.[34]

One beneficiary of his philanthropy is the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp, a residential summer camp for seriously ill children located in Ashford, Connecticut, which Newman co-founded in 1988. It is named after the gang in his film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), and the real-life, historic Hole-in-the-Wall outlaw hang-out in the mountains of northern Wyoming. Newman's college fraternity, Phi Kappa Tau, adopted his Connecticut Hole in the Wall camp as their "national philanthropy" in 1995. The original camp has expanded to become several Hole in the Wall Camps in the U.S., Ireland, France, and Israel. The camps serve 13,000 children every year, free of charge.[2]

In June 1999, Newman donated $250,000 to Catholic Relief Services to aid refugees in Kosovo.[35]

On June 1, 2007, Kenyon College announced that Newman had donated $10 million to the school to establish a scholarship fund as part of the college's current $230 million fund-raising campaign. Newman and Woodward were honorary co-chairs of a previous campaign.[36]

Newman was one of the founders of the Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy (CECP), a membership organization of CEOs and corporate chairpersons committed to raising the level and quality of global corporate philanthropy. Founded in 1999 by Newman and a few leading CEOs, CECP has grown to include more than 175 members and, through annual executive convenings, extensive benchmarking research, and best practice publications, leads the business community in developing sustainable and strategic community partnerships through philanthropy.[37] Newman was named the Most Generous Celebrity of 2008 by Givingback.org. He contributed $20,857,000 for the year of 2008 to the Newman's Own Foundation, which distributes funds to a variety of charities.[38]

Upon Newman's death, the Italian newspaper (a "semi-official" paper of the Holy See) L'Osservatore Romano published a notice lauding Newman's philanthropy. It also commented that "Newman was a generous heart, an actor of a dignity and style rare in Hollywood quarters."[39]

Newman was responsible for preserving lands around Westport, Connecticut. He lobbied the state's governor for funds for the 2011 Aspetuck Land Trust in Easton.[40] In 2011 Paul Newman's estate gifted land to Westport to be managed by the Aspetuck Land Trust.[41]

Political activism

Newman was a lifelong Democrat. For his support of Eugene McCarthy in 1968 (and effective use of television commercials in California) and his opposition to the Vietnam War, Newman was placed nineteenth on Richard Nixon's enemies list,[42] which Newman claimed was his greatest accomplishment. During the 1968 general election, Newman supported Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey and appeared in a pre-election night telethon for him. Newman was also a vocal supporter of gay rights.[43][44]

In January 1995, Newman was the chief investor of a group, including the writer E.L. Doctorow and the editor Victor Navasky, that bought the progressive-left wing periodical The Nation.[45] Newman was an occasional writer for the publication.[46]

Consistent with his work for liberal causes, Newman publicly supported Ned Lamont's candidacy in the 2006 Connecticut Democratic Primary against Senator Joe Lieberman, and was even rumored as a candidate himself, until Lamont emerged as a credible alternative. He donated to Chris Dodd's presidential campaign.[47] Newman earlier donated money to Bill Richardson's campaign for president in 2008.

He attended the first Earth Day event in Manhattan on April 22, 1970.[48]

Newman was concerned about global warming and supported nuclear energy development as a solution.[49]

Auto racing

Newman was an auto racing enthusiast, despite being colorblind, and first became interested in motorsports ("the first thing that I ever found I had any grace in") while training at the Watkins Glen Racing School for the filming of Winning, a 1969 film. Because of his love and passion for racing, Newman agreed in 1971 to star in and to host his first television special, Once Upon a Wheel, on the history of auto racing. It was produced and directed by David Winters, who co-owned a number of racing cars with Newman.[50][51] Newman's first professional event as a racer was in 1972 at Thompson International Speedway, quietly entered as "P.L. Newman", by which he continued to be known in the racing community.[52]

He was a frequent competitor in Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) events for the rest of the decade, eventually winning four national championships. He later drove in the 1979 24 Hours of Le Mans in Dick Barbour's Porsche 935 and finished in second place.[53] Newman reunited with Barbour in 2000 to compete in the Petit Le Mans.[54]

| 24 Hours of Le Mans career | |

|---|---|

| Participating years | 1979 |

| Teams | Dick Barbour Racing |

| Best finish | 2nd (1979) |

| Class wins | 1 (1979) |

From the mid-1970s to the early 1990s, he drove for the Bob Sharp Racing team, racing mainly Datsuns (later rebranded as Nissans) in the Trans-Am Series. He became closely associated with the brand during the 1980s, even appearing in commercials for them in Japan and having a special edition of the Nissan Skyline named after him. At the age of 70 years and eight days, Newman became the oldest driver to date to be part of a winning team in a major sanctioned race,[55] winning in his class at the 1995 24 Hours of Daytona.[56] Among his last major races were the Baja 1000 in 2004 and the 24 Hours of Daytona once again in 2005.[57]

During the 1976 auto racing season, Newman became interested in forming a professional auto racing team and contacted Bill Freeman who introduced Newman to professional auto racing management, and their company specialized in Can-Am, Indy Cars, and other high performance racing automobiles. The team was based in Santa Barbara, California and commuted to Willow Springs International Motorsports Park for much of its testing sessions.

Their "Newman Freeman Racing" team was very competitive in the North American Can-Am series in their Budweiser sponsored Chevrolet powered Spyder NFs. Newman and Freeman began a long and successful partnership with the Newman Freeman Racing team in the Can-Am series which culminated in the Can-Am Team Championship trophy in 1979. Newman was associated with Freeman's established Porsche racing team which allowed both Newman and Freeman to compete in S.C.C.A. and I.M.S.A. racing events together, including the Sebring 12-hour endurance sports car race. This car was sponsored by Beverly Porsche/Audi. Freeman was Sports Car Club of America's Southern Pacific National Champion during the Newman Freeman Racing period. Later Newman co-founded Newman/Haas Racing with Carl Haas, a Champ Car team, in 1983, going on to win 8 drivers' championships under his ownership. The 1996 racing season was chronicled in the IMAX film Super Speedway, which Newman narrated. He was a partner in the Atlantic Championship team Newman Wachs Racing.

Having said he would quit "when I embarrass myself", Newman competed into his 80s, winning at Lime Rock in what former co-driver Sam Posey called a "brutish Corvette" displaying his age as its number: 81.[52] He took the pole in his last professional race, in 2007 at Watkins Glen International, and in a 2008 run at Lime Rock, arranged by friends, he reportedly still did 9/10ths of his best time.[58]

Newman was posthumously inducted into the SCCA Hall of Fame at the national convention in Las Vegas, Nevada on February 21, 2009.[59]

Newman's racing life was chronicled In the documentary Winning: The Racing Life of Paul Newman.

Motorsports career results

(key)

| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Class | Laps | Pos. | Class Pos. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | |

|

Porsche 935 | IMSA+2.5 | 300 | 2nd | 1st |

Personal life

Newman was married to Jackie Witte[17] from 1949 to 1958. They had a son, Scott (1950–1978), and two daughters, Stephanie Kendall (born 1951) and Susan (born 1953).[17] Scott, who appeared in films including Breakheart Pass, The Towering Inferno, and the 1977 film Fraternity Row, died in November 1978 from a drug overdose.[60] Newman started the Scott Newman Center for drug abuse prevention in memory of his son.[61] Susan is a documentary filmmaker and philanthropist, and has Broadway and screen credits, including a starring role as one of four Beatles fans in I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978), and also a small role opposite her father in Slap Shot. She also received an Emmy nomination as co-producer of his telefilm, The Shadow Box.

Newman met actress Joanne Woodward in 1953. Shortly after filming The Long, Hot Summer in 1957, he divorced Witte. He married Woodward early in 1958. They remained married for 50 years, until his death in 2008.[62] They had three daughters: Elinor "Nell" Teresa (b. 1959), Melissa "Lissy" Stewart (b. 1961), and Claire "Clea" Olivia (b. 1965). Newman directed Nell alongside her mother in the films Rachel, Rachel and The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds.

The Newmans moved away from Hollywood in the early 1960s, buying a home and starting a family in Westport, Connecticut. They were one of the very first Hollywood movie star couples to choose to raise their families outside of California. Newman was well known for his devotion to his wife and family. When once asked about infidelity, he famously quipped, "Why go out for a hamburger when you have steak at home?"[63]

Newman was an ordained minister of the Universal Life Church.[64]

Illness and death

Newman was scheduled to make his professional stage directing debut with the Westport Country Playhouse's 2008 production of John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men, but he stepped down on May 23, 2008, citing his health concerns.[65]

In June 2008, it was widely reported that Newman had been diagnosed with lung cancer and was receiving treatment at Sloan-Kettering hospital in New York City.[66] Writer A.E. Hotchner, who partnered in the 1980s with Newman to start Newman's Own, told the Associated Press that Newman told him about the disease about 18 months prior to the interview.[67] Newman's spokesman told the press that the star was "doing nicely", but neither confirmed nor denied that he had cancer.[68]

Newman died on the morning of September 26, 2008, aged 83, surrounded by family and friends.[69][70][71] He was surrounded by his five daughters and eight grandchildren.[72] His remains were cremated after a private funeral service near his home in Westport.[73]

Filmography, awards, nominations, and honors

Newman is one of four actors to have been nominated for an Academy Award in five different decades.[29][74] The other nominees were Laurence Olivier, Michael Caine, and Jack Nicholson.[75]

In addition to the awards Newman won for specific roles, he received an honorary Academy Award in 1986 for his "many and memorable and compelling screen performances" and the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for his charity work in 1994.[74]

He received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1992 along with his wife, Joanne Woodward.[29]

In 1994, Newman and his wife received the Award for Greatest Public Service Benefiting the Disadvantaged, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[76]

Newman won Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival for The Long, Hot Summer and the Silver Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival for Nobody's Fool.[29][74]

In 1968, Newman was named "Man of the Year" by Harvard University's performance group, the Hasty Pudding Theatricals.[74]

In 2015, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 'forever stamp' honoring Newman, which went on sale September 18, 2015. It features a 1980 photograph of Newman by photographer Steve Schapiro, accompanied by text that reads: 'Actor/Philanthropist'.[77]

Since the 1970s, an event called "Newman Day" has been celebrated at Kenyon College, Bates College, Princeton University, and other American colleges. On "Newman Day", students try to drink 24 beers in 24 hours, based on a quote attributed to Newman about there being 24 beers in a case, and 24 hours in a day, and that this is surely not a mere coincidence.[78] In 2004, Newman requested that Princeton University disassociate the event from his name, due to the fact that he did not endorse the behaviors, citing his creation in 1980 of the Scott Newman Centre, "dedicated to the prevention of substance abuse through education". Princeton disavowed any responsibility for the event, responding that Newman Day is not sponsored, endorsed, or encouraged by the university itself and is solely an unofficial event among students.[79][80]

Bibliography

- Newman, Paul; Hotchner, A.E. Newman's Own Cookbook. Simon & Schuster, 1998; ISBN 0-684-84832-5.

- Newman, Paul; Hotchner, A.E. Shameless Exploitation in Pursuit of the Common Good. Doubleday Publishing, 2003; ISBN 0-385-50802-6.

Notes

- ↑ "Persons With 5 or More Acting Nominations". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. March 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Newman's Own Foundation - More than $350 Million Donated Around the World". newmansownfoundation.org. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Total Giving". newmansownfoundation.org. Retrieved 2016-06-27.

- ↑ Kaye, Leon. "How Safe Water Network's Partnership With Companies Benefits the World's Poor". triplepundit.com. Triple Pundit. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "A Global Community of Camps and Programs". seriousfunnetwork.org. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ Lax, Eric (1996). Paul Newman: A Biography. Atlanta: Turner Publishing; ISBN 1-57036-286-6.

- 1 2 Morella, Joe; Epstein, Edward Z. (1988). Paul and Joanne: A Biography of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. Delacorte Press; ISBN 0-440-50004-4.

- ↑ Profile, FilmReference.com; accessed October 21, 2015.

- 1 2 Ancestry of Paul Newman at the Wayback Machine (archived September 27, 2010). Genealogy.com; accessed October 21, 2015.

- ↑ Levy, Shawn (November 5, 2009). "Paul Newman: A Life" (excerpt). Scribd.com. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Paul Newman: A Biography". google.co.uk.

- ↑ "Paul Newman, A Big Gun at 73". Buffalo News. March 7, 1998; retrieved March 8, 2008.

- ↑ Ptičie, Obecný úrad Ptičie, pticie.host.sk; accessed October 21, 2015.(Slovak)

- ↑ "Fallece el actor Paul Newman", Elmundo.es, September 27, 2008.(Spanish)

- ↑ Skow, John. "Verdict on a Superstar", Time, December 6, 1982.

- ↑ "Arthur S. Newman Jr.". IMDb. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Paul Newman biography, Tiscali.co.uk.com; accessed October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Paul Newman at The Cleveland Play House Children's Theatre". The Cleveland Memory Project. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ↑ Hastings, Max (2008). Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944–45. Random House; ISBN 0-307-26351-7.

- ↑ "Honoring Those Who Serve". Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Newman gives $10M to Ohio alma mater". USA Today. June 2, 2007. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ↑ Franzene, Jessica, "Theologians & Thespians," in Welcome Home, a realtors' guide to property history in the Lake Geneva region, August 2012

- ↑ Borden, Marian Edelman (November 2, 2010). "Paul Newman: A Biography". ISBN 978-0-313-38310-6.

- ↑ Levant, Oscar (1969). The Unimportance of Being Oscar. Pocket Books. p. 56; ISBN 0-671-77104-3.

- ↑ "Actor Paul Newman's dramatic roots were sprouted on Staten Island". SILive.com. Staten Island Advance. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ↑ Forgotten-NY Neighborhoods: St. George: Staten Island's Wonderland at the Wayback Machine (archived February 13, 2009)

- ↑ "Ice From Space". Tales of Tomorrow. Season 1. Episode 43. August 8, 1952.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Paul Newman at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Weiner, Ed; Editors of TV Guide (1992). The TV Guide TV Book: 40 Years of the All-Time Greatest Television Facts, Fads, Hits, and History (First ed.). New York: Harper Collins. p. 118.

- ↑ "Inside The Actors Studio – Paul Newman". YouTube. June 8, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Paul Newman". Television Academy. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Paul Newman quits films after stellar career", News.com.au. May 27, 2007. Hollywood star Newman to retire, bbc.co.uk, May 27, 2007.

- ↑ "Paul Newman says he will die at home", Herald Sun, August 9, 2008. Archived January 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Paul Newman Philanthropy". November 14, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Paul Newman donates $10 mln to Kenyon College". Reuters. June 2, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ↑ "CECP – Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy". Corporatephilanthropy.org. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ↑ "The Giving Back 30". The Giving Back Fund. November 1, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- ↑ Pattison, Mark (September 30, 2008). "Catholic film critics laud actor Paul Newman's career, generosity". Catholic News Service. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ↑ Christopher Brooks; Catherine Brooks (April 22, 2011). 60 Hiles Within 60 Miles: New York City. ReadHowYouWant.com. pp. 620–621. ISBN 978-1-4596-1793-3. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ↑ Hennessy, Christina (October 20, 2011). "Sightseeing: Newman Poses Nature Preserve may have marquee name, but nature is the star". The Stamford Advocate. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ↑ "List of White House 'Enemies' and Memo Submitted by Dean to the Ervin Committee". Facts on File. Archived from the original on June 21, 2003. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ↑ Levy 2010, p. 241.

- ↑ Borden 2010, p. 96.

- ↑ "Liberal Weekly The Nation Sold To Paul Newman, Others". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. January 14, 1995. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ↑ Newman, Paul (August 21, 2000). "Paul Newman:In His Own Words". The Nation. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ↑ Dodd Gets Financial Boost From Celebs, WFSB.com, April 17, 2007. Archived May 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Winn, Steven (September 28, 2008). "Paul Newman an icon of cool masculinity". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Cool Hand Nuke: Paul Newman endorses power plant". USA Today. May 23, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ↑ "Once Upon A Wheel". Davidwinters.net. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ↑ "David Winters Tribute Site". Davidwinters.net. April 1, 2003. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- 1 2 "Racing community saddened by death of Paul Newman". Autoweek. September 26, 2008. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ↑ "XLVII Grand Prix d'Endurance les 24 Heures du Mans 1979". Le Mans & F2 Register. May 2, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ↑ "American Le Mans Series 2000". World Sports Racing Prototypes. October 2, 2005. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ↑ Vaughn, Mark (October 6, 2008). "Paul Newman 1925–2008". AutoWeek. 58 (40): 43.

- ↑ "International Motor Sports Association 1995". World Sports Racing Prototypes. February 14, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ↑ "Grand-American Road Racing Championship 2005". World Sports Racing Prototypes. December 17, 2005. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ↑ "PL Newman from Lime Rock Connecticut". DRIVINGLine. April 17, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ↑ "Newman Leads List of New SCCA Hall of Fame Inductees". Sports Car Club of America. December 3, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ↑ Clark, Hunter S. Profile, Time.com, February 17, 1986.

- ↑ Welcome, scottnewmancenter.org; accessed October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Remembering Paul Newman", People.com, September 27, 2008.

- ↑ "Concern about Paul Newman's health". Daily News. New York. March 12, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2008. Ellen, Barbara (October 8, 2006). "It's an age-old quandary — why do men, like dogs, stray?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ↑ McClanahan, Ed (2003). Famous People I Have Known. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 4–. ISBN 0-8131-9069-X.

- ↑ "Citing Health, Newman Steps Down as Director of Westport's Of Mice and Men". Playbill. May 23, 2008. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Paul Newman has cancer", The Daily Telegraph, June 9, 2008.

- ↑ Christoffersen, John. "Longtime friend: Paul Newman has cancer", cbsnews.com, June 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Newman says he is 'doing nicely'", bbc.co.uk, June 11, 2008.

- ↑ AP. "Acting legend Paul Newman dies at 83". msnbc. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ↑ Leask, David. "Paul Newman, Hollywood legend, dies at 83". ScotlandonSunday.scotsman.com. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Film star, businessman, philanthropist Paul Newman dies at 83", Detroit Free Press, September 28, 2008; retrieved 2015-07-22

- ↑ Levy, Shawn. "Paul Newman: A Life". Crown Publishing Group; retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ↑ Hodge, Lisa. "Legend laid to rest in private family ceremony", ahlanlive.com; retrieved October 11, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Paul Newman at the TCM Movie Database

- ↑ "IMDb - Movies, TV and Celebrities". IMDb. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ↑ "National - Jefferson Awards". Jefferson Awards.

- ↑ "U.S. Postal Service to Issue Paul Newman Forever Stamp", usps.com, June 29, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-23

- ↑ The Daily Princetonian: Carol Lu, "If I had a nickel for every beer I drank today." April 24, 2007.

- ↑ "Binge drink ritual upsets actor". BBC News. April 24, 2004.

- ↑ Cheng, Jonathan (April 24, 2004). "Newman's Day – forget it, star urges drinkers". Sydney Morning Herald.

References

- Dherbier, Yann-Brice; Verlhac, Pierre-Henri (2006). Paul Newman: A Life in Pictures. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-5726-0. OCLC 71146543.

- Demers, Jenifer. Paul Newman: the Dream has Ended!. Createspace, 2008; ISBN 1-4404-3323-2

- Lax, Eric. Paul Newman: a Biography. Turner Publishing, Incorporated, 1999; ISBN 1-57036-286-6.

- Levy, Shawn (2009). Paul Newman: A Life. Harmony Books. ISBN 9780307353757.

- Morella, Joe; Epstein, Edward Z. Paul and Joanne: A Biography of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. Delacorte Press, 1988; ISBN 0-440-50004-4.

- O'Brien, Daniel. Paul Newman. Faber & Faber, Limited, 2005; ISBN 0-571-21987-X.

- Oumano, Elena. Paul Newman. St. Martin's Press, 1990; ISBN 0-517-05934-7.

- Quirk, Lawrence J. The Films of Paul Newman. Taylor Pub., 1986; ISBN 0-8065-0385-8.

- Thomson, Kenneth. The Films of Paul Newman. 1978; ISBN 0-912616-87-3.

Further reading

- Hinton, Susan (1967). The Outsiders. USA: Viking Press, Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-670-53257-6. OCLC 64396432.

- Quirk, Lawrence J. (1971). The Films of Paul Newman. New York, NY: Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-0233-9. OCLC 171115.

- Hamblett, Charles (1975). Paul Newman. Chicago, IL: H. Regnery. ISBN 978-0-8092-8236-4. OCLC 1646636.

- Godfrey, Lionel (1979). Paul Newman Superstar: A Critical Biography. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-59819-8. OCLC 4739913.

- Landry, J. C. (1983). Paul Newman. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-036189-8. OCLC 9556372.

- Morella, Joe; Epstein, Edward Z. (1988). Paul and Joanne: A Biography of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. New York, NY: Delacorte Press. ISBN 978-0-440-50004-9. OCLC 18016049.

- Stern, Stewart (1989). No Tricks in My Pocket: Paul Newman Directs. New York, NY: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1120-3. OCLC 18780705.

- Netter, Susan (1989). Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. London, England: Piatkus. ISBN 978-0-86188-869-6. OCLC 19778734.

- Oumano, Elena (1989). Paul Newman. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-02627-1. OCLC 18558929.

- Lax, Eric (1996). Newman: Paul Newman, A Celebration. London, UK: Pavilion. ISBN 978-1-85793-730-5. OCLC 37355715.

- Lax, Eric (1996). Paul Newman: A Biography. Atlanta, GA: Turner Pub. ISBN 978-1-57036-286-6. OCLC 33667112.

- Quirk, Lawrence J. (1996). Paul Newman. Dallas, TX: Taylor Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-87833-962-4. OCLC 35884602.

- O'Brien, Daniel (2004). Paul Newman. London, UK: Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-21986-5. OCLC 56658601.

- Demers, Jenifer (2008). Paul Newman: The Dream has Ended!. California: Createspace. ISBN 978-1-4404-3323-8.

- Hotchner, A.E. (2010). Paul and Me: Fifty-three Years of Adventures and Misadventures with My Pal, Paul Newman. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-53233-4.

External links

| Wikinews has related news: Hollywood legend Paul Newman dies of cancer age 83 |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Paul Newman |

- Paul Newman at the Internet Movie Database

- Paul Newman at the Internet Broadway Database

- Paul Newman at the TCM Movie Database

- Paul Newman driver statistics at Racing-Reference

- Newman's Own

- Newman's Own Foundation

- Paul Newman at Emmys.com

| Media offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by |

President of the Actors Studio 1982–1994 |

Succeeded by Al Pacino Ellen Burstyn Harvey Keitel |