Binary scaling

Binary scaling is a computer programming technique used mainly by embedded C, DSP and assembler programmers to perform a pseudo floating point using integer arithmetic.

Overview

Binary scaling is both faster and more accurate than directly using floating point instructions; however, care must be taken not to cause an arithmetic overflow.

A position for the virtual 'binary point' is taken, and then subsequent arithmetic operations determine the 'binary point'.

Binary points obey the mathematical laws of exponentiation.

To give an example, a common way to use integer arithmetic to simulate floating point is to multiply the coefficients by 65536.

Using binary scientific notation, this will place the binary point at 1B16.

For instance, to represent 1.2 and 5.6 floating point real numbers as 1B16 one multiplies them by 216, giving 78643 and 367001.

Multiplying these together gives

28862059643

To convert it back to 1B16, divide it by 216.

This gives 440400B16, which when converted back to a floating point number (by dividing again by 216, but holding the result as floating point) gives 6.71999. The correct floating point result is 6.72.

The scaling range here is for any number between 65535.9999 and −65536.0 with 16 bits to hold fractional quantities (of course assuming the use of a 64 bit result register). Note that some computer architectures may restrict arithmetic to 32 bit results. In this case extreme care must be taken not to overflow the 32 bit register. For other number ranges the binary scale can be adjusted for optimum accuracy.

Re-scaling after multiplication

The example above for a B16 multiplication is a simplified example. Re-scaling depends on both the B scale value and the word size. B16 is often used in 32 bit systems because it works simply by multiplying and dividing by 65536 (or shifting 16 bits).

Consider the Binary Point in a signed 32 bit word thus:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 S X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

where S is the sign bit and X are the other bits.

Placing the binary point at

- 0 gives a range of −1.0 to 0.999999.

- 1 gives a range of −2.0 to 1.999999

- 2 gives a range of −4.0 to 3.999999 and so on.

When using different B scalings the complete B scaling formula must be used.

Consider a 32 bit word size, and two variables, one with a B scaling of 2 and the other with a scaling of 4.

1.4 @ B2 is 1.4 * (2wordsize-2-1) == 1.4 * 2 ^ 29 == 0x2CCCCCCD

Note that here the 1.4 values is very well represented with 30 fraction bits. A 32 bit floating-point number has 23 bits to store the fraction in. This is why B scaling is always more accurate than floating point of the same word size. This is especially useful in integrators or repeated summing of small quantities where rounding error can be a subtle but very dangerous problem, when using floating point.

Now a larger number 15.2 at B4.

15.2 @ B4 is 15.2 * (2 ^ (wordsize-4-1)) == 15.2 * 2 ^ 27 == 0x7999999A

Again the number of bits to store the fraction is 28 bits. Multiplying these 32 bit numbers give the 64 bit result 0x1547AE14A51EB852

This result is in B7 in a 64 bit word. Shifting it down by 32 bits gives the result in B7 in 32 bits.

0x1547AE14

To convert back to floating point, divide this by (2^(wordsize-7-1)) == 21.2800000099

Various scalings may be used. B0 for instance can be used to represent any number between -1 and 0.999999999.

Binary angles

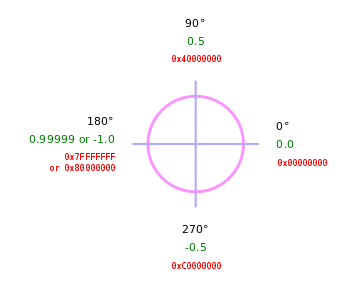

Binary angles are mapped using B0, with 0 as 0 degrees, 0.5 as 90° (or ), −1.0 or 0.9999999 as 180° (or π) and −0.5 as 270° (or ). When these binary angles are added using normal two's complement mathematics, the rotation of the angles is correct, even when crossing the sign boundary (this of course does away with checks for angle ≥ 360° when handling normal degrees[1]).

The terms Binary Angular Measurement System (BAMS)[2][3] and brads (binary radians or binary degree) refer to implementations of binary angles. They find use in robotics, navigation,[4] computer games,[5] digital sensors[6] and weapon systems' digital communications[3]

No matter what bit-pattern is stored in a binary angle, when it is multiplied by 360° (or 2π) using standard signed fixed-point arithmetic, the result is always a valid angle in the range of −180° degrees (−π radians) to +180° degrees (+π radians). In some cases, it is convenient to use unsigned multiplication (rather than signed multiplication) on a binary angle, which gives the correct angle in the range of 0 to +360° degrees (+2π radians or +1 turn). Compared to storing angles in a binary angle format, storing angles in any other format inevitably results in some bit patterns giving "angles" outside that range, requiring extra steps to range-reduce the value to the desired range, or results in some bit patterns that are not valid angles at all (NaN), or both.

Application of binary scaling techniques

Binary scaling techniques were used in the 1970s and 80s for real time computing that was mathematically intensive, such as flight simulation. The code was often commented with the binary scalings of the intermediate results of equations.

Binary scaling is still used in many DSP applications and custom made microprocessors are usually based on binary scaling techniques.

Binary scaling is currently used in the DCT used to compress JPEG images in utilities such as the GIMP.

Although floating point has taken over to a large degree, where speed and extra accuracy are required, binary scaling works on simpler hardware and is more accurate when the range of values is known in advance.

See also

- Fixed-point arithmetic – general discussion about using scaling factors for integer math operations

- Libfixmath – a library written in C for fixed-point math

- Q (number format)

References

- ↑ Angles, integers, and modulo arithmetic Shawn Hargreaves, blogs.msdn.com

- ↑ Binary Angular Measurement System acronyms.thefreedictionary

- 1 2 BINARY ANGULAR MEASUREMENT Archived December 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. www.tpub.com

- ↑ Real-Time Systems Design and Analysis Chapter 7.5.3, Binary Angular Measure , Phillip A. LaPlante, page via www.globalspec.com

- ↑ Doom 1993 code review Fabien Sanglard, section "Walls", 13/1/2010, fabiensanglard.net

- ↑ Hitachi HM55B Compass Module (#29123) Archived July 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. pdf via www.parallax.com via www.hobbyengineering.com