IEEE floating point

The IEEE Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic (IEEE 754) is a technical standard for floating-point computation established in 1985 by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). The standard addressed many problems found in the diverse floating point implementations that made them difficult to use reliably and portably. Many hardware floating point units now use the IEEE 754 standard.

The standard defines:

- arithmetic formats: sets of binary and decimal floating-point data, which consist of finite numbers (including signed zeros and subnormal numbers), infinities, and special "not a number" values (NaNs)

- interchange formats: encodings (bit strings) that may be used to exchange floating-point data in an efficient and compact form

- rounding rules: properties to be satisfied when rounding numbers during arithmetic and conversions

- operations: arithmetic and other operations (such as trigonometric functions) on arithmetic formats

- exception handling: indications of exceptional conditions (such as division by zero, overflow, etc.)

The current version, IEEE 754-2008 published in August 2008, includes nearly all of the original IEEE 754-1985 standard and the IEEE Standard for Radix-Independent Floating-Point Arithmetic (IEEE 854-1987).

Standard development

The current version, IEEE 754-2008 published in August 2008, is derived from and replaces IEEE 754-1985, the previous version, following a seven-year revision process, chaired by Dan Zuras and edited by Mike Cowlishaw.

The international standard ISO/IEC/IEEE 60559:2011 (with content identical to IEEE 754-2008) has been approved for adoption through JTC1/SC 25 under the ISO/IEEE PSDO Agreement[1] and published.[2]

The binary formats in the original standard are included in the new standard along with three new basic formats (one binary and two decimal). To conform to the current standard, an implementation must implement at least one of the basic formats as both an arithmetic format and an interchange format.

As of September 2015, the standard is being revised to incorporate clarifications and errata.[3][4]

Formats

An IEEE 754 format is a "set of representations of numerical values and symbols". A format may also include how the set is encoded.

A format comprises:

- Finite numbers, which may be either base 2 (binary) or base 10 (decimal). Each finite number is described by three integers: s = a sign (zero or one), c = a significand (or 'coefficient'), q = an exponent. The numerical value of a finite number is

(−1)s × c × bq

where b is the base (2 or 10), also called radix. For example, if the base is 10, the sign is 1 (indicating negative), the significand is 12345, and the exponent is −3, then the value of the number is −11 × 12345 × 10−3 = −1 × 12345 × .001 = −12.345. - Two infinities: +∞ and −∞.

- Two kinds of NaN: a quiet NaN (qNaN) and a signaling NaN (sNaN). A NaN may carry a payload that is intended for diagnostic information indicating the source of the NaN. The sign of a NaN has no meaning, but it may be predictable in some circumstances.

The possible finite values that can be represented in a format are determined by the base b, the number of digits in the significand (precision p), and the exponent parameter emax:

- c must be an integer in the range zero through bp−1 (e.g., if b=10 and p=7 then c is 0 through 9999999)

- q must be an integer such that 1−emax ≤ q+p−1 ≤ emax (e.g., if p=7 and emax=96 then q is −101 through 90).

Hence (for the example parameters) the smallest non-zero positive number that can be represented is 1×10−101 and the largest is 9999999×1090 (9.999999×1096), and the full range of numbers is −9.999999×1096 through 9.999999×1096. The numbers −b1−emax and b1−emax (here, −1×10−95 and 1×10−95) are the smallest (in magnitude) normal numbers; non-zero numbers between these smallest numbers are called subnormal numbers.

Zero values are finite values with significand 0. These are signed zeros, the sign bit specifies if a zero is +0 (positive zero) or −0 (negative zero).

Representation and encoding in memory

Some numbers may have several representations in the model that has just been described. For instance, if b=10 and p=7, −12.345 can be represented by −12345×10−3, −123450×10−4, and −1234500×10−5. However, for most operations, such as arithmetic operations, the result (value) does not depend on the representation of the inputs.

For the decimal formats, any representation is valid, and the set of these representations is called a cohort. When a result can have several representations, the standard specifies which member of the cohort is chosen.

On the contrary, for the binary formats, the representation is made unique by choosing the smallest representable exponent (for non-zero, finite numbers). In particular, in the normal range, the leading bit of the significand is non-zero, thus always 1. As a consequence, this leading bit 1 of the normal numbers need not be represented in the memory encoding. This rule is called leading bit convention, implicit bit convention, or hidden bit convention.

Basic and interchange formats

The standard defines five basic formats that are named for their numeric base and the number of bits used in their interchange encoding. There are three binary floating-point basic formats (encoded with 32, 64 or 128 bits) and two decimal floating-point basic formats (encoded with 64 or 128 bits). The binary32 and binary64 formats are the single and double formats of IEEE 754-1985. A conforming implementation must fully implement at least one of the basic formats.

The standard also defines interchange formats, which generalize these basic formats.[5] For the binary ones, the leading bit convention is required. The following table summarizes the smallest interchange formats (including the basic ones).

| Name | Common name | Base | Digits | Decimal digits | Exponent bits | Decimal E max | Exponent bias[6] | E min | E max | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| binary16 | Half precision | 2 | 11 | 3.31 | 5 | 4.51 | 24−1 = 15 | −14 | +15 | not basic |

| binary32 | Single precision | 2 | 24 | 7.22 | 8 | 38.23 | 27−1 = 127 | −126 | +127 | |

| binary64 | Double precision | 2 | 53 | 15.95 | 11 | 307.95 | 210−1 = 1023 | −1022 | +1023 | |

| binary128 | Quadruple precision | 2 | 113 | 34.02 | 15 | 4931.77 | 214−1 = 16383 | −16382 | +16383 | |

| binary256 | Octuple precision | 2 | 237 | 71.34 | 19 | 78913.2 | 218−1 = 262143 | −262142 | +262143 | not basic |

| decimal32 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 7.58 | 96 | 101 | −95 | +96 | not basic | |

| decimal64 | 10 | 16 | 16 | 9.58 | 384 | 398 | −383 | +384 | ||

| decimal128 | 10 | 34 | 34 | 13.58 | 6144 | 6176 | −6143 | +6144 | ||

Note that in the table above, the minimum exponents listed are for normal numbers; the special subnormal number representation allows even smaller numbers to be represented (with some loss of precision). For example, the smallest double-precision number greater than zero that can be represented in that form is 2−1074 (because 1074 = 1022 + 53 − 1).

Decimal digits is digits × log10 base, this gives an approximate precision in decimal.

Decimal E max is Emax × log10 base, this gives the maximum exponent in decimal.

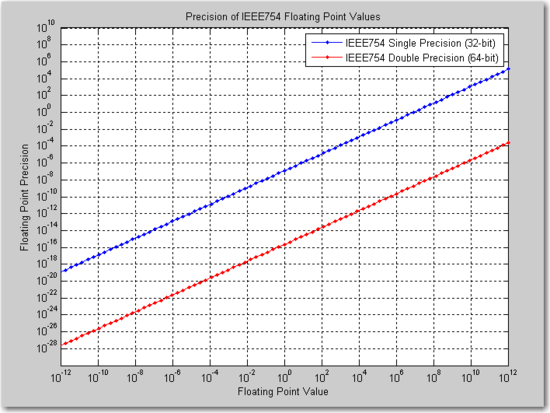

As stated previously, the binary32 and binary64 formats are identical to the single and double formats respectively of IEEE 754-1985 and are two of the most common formats used today. The figure below shows the absolute precision for both the binary32 and binary64 formats in the range of 10−12 to 10+12. Such a figure can be used to select an appropriate format given the expected value of a number and the required precision.

Extended and extendable precision formats

The standard specifies extended and extendable precision formats, which are recommended for allowing a greater precision than that provided by the basic formats.[7] An extended precision format extends a basic format by using more precision and more exponent range. An extendable precision format allows the user to specify the precision and exponent range. An implementation may use whatever internal representation it chooses for such formats; all that needs to be defined are its parameters (b, p, and emax). These parameters uniquely describe the set of finite numbers (combinations of sign, significand, and exponent for the given radix) that it can represent.

The standard does not require an implementation to support extended or extendable precision formats.

The standard recommends that languages provide a method of specifying p and emax for each supported base b.[8]

The standard recommends that languages and implementations support an extended format which has a greater precision than the largest basic format supported for each radix b.[9]

For an extended format with a precision between two basic formats the exponent range must be as great as that of the next wider basic format. So for instance a 64-bit extended precision binary number must have an 'emax' of at least 16383. The x87 80-bit extended format meets this requirement.

Interchange formats

Interchange formats are intended for the exchange of floating-point data using a fixed-length bit-string for a given format.

For the exchange of binary floating-point numbers, interchange formats of length 16 bits, 32 bits, 64 bits, and any multiple of 32 bits ≥128 are defined. The 16-bit format is intended for the exchange or storage of small numbers (e.g., for graphics).

The encoding scheme for these binary interchange formats is the same as that of IEEE 754-1985: a sign bit, followed by w exponent bits that describe the exponent offset by a bias, and p−1 bits that describe the significand. The width of the exponent field for a k-bit format is computed as w = round(4 log2(k))−13. The existing 64- and 128-bit formats follow this rule, but the 16- and 32-bit formats have more exponent bits (5 and 8) than this formula would provide (3 and 7, respectively).

As with IEEE 754-1985, there is some flexibility in the encoding of signaling NaN.

For the exchange of decimal floating-point numbers, interchange formats of any multiple of 32 bits are defined.

The encoding scheme for the decimal interchange formats similarly encodes the sign, exponent, and significand, but two different bit-level representations are defined. Interchange is complicated by the fact that some external indicator of the representation in use is required. The two options allow the significand to be encoded as a compressed sequence of decimal digits (using densely packed decimal) or alternatively as a binary integer. The former is more convenient for direct hardware implementation of the standard, while the latter is more suited to software emulation on a binary computer. In either case the set of numbers (combinations of sign, significand, and exponent) that may be encoded is identical, and special values (±zero, ±infinity, quiet NaNs, and signaling NaNs) have identical binary representations.

Rounding rules

The standard defines five rounding rules. The first two rules round to a nearest value; the others are called directed roundings:

Roundings to nearest

- Round to nearest, ties to even – rounds to the nearest value; if the number falls midway it is rounded to the nearest value with an even (zero) least significant bit, which occurs 50% of the time; this is the default for binary floating-point and the recommended default for decimal.

- Round to nearest, ties away from zero – rounds to the nearest value; if the number falls midway it is rounded to the nearest value above (for positive numbers) or below (for negative numbers); this is intended as an option for decimal floating point.

Directed roundings

- Round toward 0 – directed rounding towards zero (also known as truncation).

- Round toward +∞ – directed rounding towards positive infinity (also known as rounding up or ceiling).

- Round toward −∞ – directed rounding towards negative infinity (also known as rounding down or floor).

| Mode / Example Value | +11.5 | +12.5 | −11.5 | −12.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| to nearest, ties to even | +12.0 | +12.0 | −12.0 | −12.0 |

| to nearest, ties away from zero | +12.0 | +13.0 | −12.0 | −13.0 |

| toward 0 | +11.0 | +12.0 | −11.0 | −12.0 |

| toward +∞ | +12.0 | +13.0 | −11.0 | −12.0 |

| toward −∞ | +11.0 | +12.0 | −12.0 | −13.0 |

Required operations

Required operations for a supported arithmetic format (including the basic formats) include:

- Arithmetic operations (add, subtract, multiply, divide, square root, fused multiply–add, remainder)[10][11]

- Conversions (between formats, to and from strings, etc.)[12][13]

- Scaling and (for decimal) quantizing[14][15]

- Copying and manipulating the sign (abs, negate, etc.)[16]

- Comparisons and total ordering[17][18]

- Classification and testing for NaNs, etc.[19]

- Testing and setting flags[20]

- Miscellaneous operations.

Total-ordering predicate

The standard provides a predicate totalOrder which defines a total ordering for all floating numbers for each format. The predicate agrees with the normal comparison operations when they say one floating point number is less than another. The normal comparison operations however treat NaNs as unordered and compare −0 and +0 as equal. The totalOrder predicate will order these cases, and it also distinguishes between different representations of NaNs and between the same decimal floating point number encoded in different ways.[17]

Exception handling

The standard defines five exceptions, each of which returns a default value and has a corresponding status flag that (except in certain cases of underflow) is raised when the exception occurs. No other exception handling is required, but additional non-default alternatives are recommended (see below).

The five possible exceptions are:

- Invalid operation (e.g., square root of a negative number) (returns qNaN by default).

- Division by zero (an operation on finite operands gives an exact infinite result, e.g., 1/0 or log(0)) (returns ±infinity by default).

- Overflow (a result is too large to be represented correctly) (returns ±infinity by default (for round-to-nearest mode)).

- Underflow (a result is very small (outside the normal range) and is inexact) (returns a denormalized value by default).

- Inexact (returns correctly rounded result by default).

These are the same five exceptions as were defined in IEEE 754-1985, but the division by zero exception has been extended to operations other than the division.

For decimal floating point, there are additional exceptions along with the above:[21][22]

- Clamped (a result's exponent is too large for the destination format). By default, trailing zeros will be added to the coefficient to reduce the exponent to the largest usable value. If this is not possible (because this would cause the number of digits needed is more than the destination format) then overflow occurs.

- Rounded (a result's coefficient requires more digits than the destination format provides). The inexact is signaled if any non-zero digits are discarded.

Additionally, operations like quantize when either operand is infinite, or when the result does not fit the destination format, will also signal invalid operation exception.[23]

Recommendations

Alternate exception handling

The standard recommends optional exception handling in various forms, including presubstitution of user-defined default values, and traps (exceptions that change the flow of control in some way) and other exception handling models which interrupt the flow, such as try/catch. The traps and other exception mechanisms remain optional, as they were in IEEE 754-1985.

Recommended operations

Clause 9 in the standard recommends fifty operations, that language standards should define.[24] These are all optional (not required in order to conform to the standard).

Recommended arithmetic operations, which must round correctly:[25]

- ex, 2x, 10x

- ex − 1, 2x − 1, 10x − 1

- loge(x), log2(x), log10(x)

- loge(1 + x), log2(1 + x), log10(1 + x)

- √x2 + y2

- 1/√x

- (1 + x)n

- x1/n

- xn, xy

- sin(x), cos(x), tan(x)

- asin(x), acos(x), atan(x), atan2(y,x)

- sinPi(x) = sin(πx), cosPi(x) = cos(πx)

- atanPi(x) = atan(x)/π, atan2Pi(y,x) = atan2(y,x)/π

- sinh(x), cosh(x), tanh(x)

- asinh(x), acosh(x), atanh(x)

The asinPi, acosPi and tanPi functions are not part of the standard because the feeling was that they were less necessary.[26] The first two are mentioned in a paragraph, but this is regarded as an error.[27]

The operations also include setting and accessing dynamic mode rounding direction,[28] and implementation-defined vector reduction operations such as sum, scaled product, and dot product, whose accuracy is unspecified by the standard.[29]

Expression evaluation

The standard recommends how language standards should specify the semantics of sequences of operations, and points out the subtleties of literal meanings and optimizations that change the value of a result. By contrast the previous 1985 version of the standard left aspects of the language interface unspecified, which led to inconsistent behaviour between compilers, or different optimization levels in a single compiler.

Programming languages should allow a user to specify a minimum precision for intermediate calculations of expressions for each radix. This is referred to as "preferredWidth" in the standard, and it should be possible to set this on a per block basis. Intermediate calculations within expressions should be calculated, and any temporaries saved, using the maximum of the width of the operands and the preferred width, if set. Thus for instance a compiler targeting x87 floating point hardware should have a means of specifying that intermediate calculations must use doubled extended format. The stored value of a variable must always be used when evaluating subsequent expressions, rather than any precursor from before rounding and assigning to the variable.

Reproducibility

The IEEE 754-1985 allowed many variations in implementations (such as the encoding of some values and the detection of certain exceptions). IEEE 754-2008 has strengthened up many of these, but a few variations still remain (especially for binary formats). The reproducibility clause recommends that language standards should provide a means to write reproducible programs (i.e., programs that will produce the same result in all implementations of a language), and describes what needs to be done to achieve reproducible results.

Character representation

The standard requires operations to convert between basic formats and external character sequence formats.[30] Conversions to and from a decimal character format are required for all formats. Conversion to an external character sequence must be such that conversion back using round to even will recover the original number. There is no requirement to preserve the payload of a NaN or signaling NaN, and conversion from the external character sequence may turn a signaling NaN into a quiet NaN.

The original binary value will be preserved by converting to decimal and back again using:[31]

- 5 decimal digits for binary16

- 9 decimal digits for binary32

- 17 decimal digits for binary64

- 36 decimal digits for binary128

For other binary formats the required number of decimal digits is

where p is the number of significant bits in the binary format, e.g. 24 bits for binary32.

(Note: as an implementation limit, correct rounding is only guaranteed for the number of decimal digits above plus 3 for the largest binary format supported. For instance if binary32 is the largest supported binary format supported, then a conversion from a decimal external sequence with 12 decimal digits is guaranteed to be correctly rounded when converted to binary32; but conversion of a sequence of 13 decimal digits is not; however the standard recommends that implementations impose no such limit.)

When using a decimal floating point format the decimal representation will be preserved using:

- 7 decimal digits for decimal32

- 16 decimal digits for decimal64

- 34 decimal digits for decimal128

Algorithms, with code, for correctly rounded conversion from binary to decimal and decimal to binary are discussed in [32] and for testing in.[33]

See also

- Coprocessor

- C99 for code examples demonstrating access and use of IEEE 754 features.

- Floating point, for history, design rationale and example usage of IEEE-754 features.

- Fixed point arithmetic, for an alternative approach at computation with rational numbers (especially beneficial when the mantissa range is known, fixed, or bound at compile time).

- Half precision – Single precision – Double precision – Quadruple precision – Extended precision.

- IBM System z9, the first CPU to implement IEEE 754-2008 decimal arithmetic (using hardware microcode)

- IBM z10, IBM z196, IBM zEC12, and IBM z13, CPUs that implement IEEE 754-2008 decimal arithmetic fully in hardware

- ISO/IEC 10967 Language independent arithmetic (LIA)

- Minifloat, low-precision binary floating-point formats following IEEE 754 principles

- POWER6, POWER7, and POWER8 CPUs that implement IEEE 754-2008 decimal arithmetic fully in hardware

- strictfp, a keyword in the Java programming language that restricts arithmetic to IEEE 754 single and double precision to ensure reproducibility across common hardware platforms.

- The table-maker's dilemma for more about the correct rounding of functions.

References

- ↑ FW: ISO/IEC/IEEE 60559 (IEEE Std 754-2008)

- ↑ ISO/IEC/IEEE 60559:2011 - Information technology - Microprocessor Systems - Floating-Point arithmetic

- ↑ http://speleotrove.com/misc/IEEE754-errata.html

- ↑ http://754r.ucbtest.org/

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §3.6

- ↑ Cowlishaw, Mike. "Decimal Arithmetic Encodings" (PDF). IBM. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §3.7

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §3.7 states, "Language standards should define mechanisms supporting extendable precision for each supported radix."

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §3.7 states, "Language standards or implementations should support an extended precision format that extends the widest basic format that is supported in that radix."

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.3.1

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.4.1

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.4.2

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.4.3

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.3.2

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.3.3

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.5.1

- 1 2 IEEE 754 2008, §5.10

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.11

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.7.2

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.7.4

- ↑ 9.4. decimal — Decimal fixed point and floating point arithmetic — Python v2.7.3 documentation

- ↑ Decimal Arithmetic - Exceptional conditions

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §7.2(h)

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, Clause 9

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §9.2

- ↑ Missing functions tanPi, asinPi and acosPi

- ↑ Cowlishaw, Mike, IEEE 754-2008 errata 2013.12.19

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §9.3

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §9.4

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.12

- ↑ IEEE 754 2008, §5.12.2

- ↑ Gay, David M. (November 30, 1990). "Correctly rounded binary-decimal and decimal-binary conversions". Numerical Analysis Manuscript. Murry Hill, NJ, USA: AT&T Laboratories. 90-10

- ↑ Paxson, Vern; Kahn, William (May 22, 1991). "A Program for Testing IEEE Decimal–Binary Conversion". Manuscript. Retrieved March 28, 2012

Standard

- IEEE Computer Society (August 29, 2008). "IEEE Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic". IEEE. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2008.4610935. ISBN 978-0-7381-5753-5. IEEE Std 754-2008

- ISO/IEC/IEEE 60559:2011

Secondary references

- Decimal floating-point arithmetic, FAQs, bibliography, and links

- Comparing binary floats

- IEEE 754 Reference Material

- IEEE 854-1987 – History and minutes

- Supplementary readings for IEEE 754. Includes historical perspectives.

Further reading

- Goldberg, David (March 1991). "What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic" (PDF). ACM Computing Surveys. 23 (1): 5–48. doi:10.1145/103162.103163. Retrieved 2016-01-20. (, )

- Hecker, Chris (February 1996). "Let's Get To The (Floating) Point" (PDF). Game Developer Magazine: 19–24. ISSN 1073-922X.

- Severance, Charles (March 1998). "IEEE 754: An Interview with William Kahan" (PDF). IEEE Computer. 31 (3): 114–115. doi:10.1109/MC.1998.660194. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- Cowlishaw, Mike (June 2003). "Decimal Floating-Point: Algorism for Computers" (PDF). Proceedings 16th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic. Los Alamitos, Calif.: IEEE Computer Society: 104–111. ISBN 0-7695-1894-X. Retrieved 14 November 2014.. (Note: Algorism is not a misspelling of the title; see also algorism.)

- Monniaux, David (May 2008). "The pitfalls of verifying floating-point computations". ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems. 30 (3): article #12. doi:10.1145/1353445.1353446. ISSN 0164-0925.: A compendium of non-intuitive behaviours of floating-point on popular architectures, with implications for program verification and testing.

- Muller, Jean-Michel; Brisebarre, Nicolas; de Dinechin, Florent; Jeannerod, Claude-Pierre; Lefèvre, Vincent; Melquiond, Guillaume; Revol, Nathalie; Stehlé, Damien; Torres, Serge (2010). Handbook of Floating-Point Arithmetic (1 ed.). Birkhäuser. doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4705-6. ISBN 978-0-8176-4704-9. LCCN 2009939668.

- Overton, Michael L. (2001). Written at Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University, New York, USA. Numerical Computing with IEEE Floating Point Arithmetic (1 ed.). Philadelphia, USA: SIAM. doi:10.1137/1.9780898718072. ISBN 978-0-89871-482-1. 978-0-89871-571-2, 0-89871-571-7. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- Cleve Moler on Floating Point numbers

External links

| The Wikibook Floating Point has a page on the topic of: special numbers specified in the IEEE 754 standard |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to IEEE 754. |

- IEEE pages: 754-1985 - IEEE Standard for Binary Floating-Point Arithmetic, 754-2008 - IEEE Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic

- Online IEEE 754 binary calculators