Prince-Bishopric of Warmia

| Prince-Bishopric of Warmia | ||||||||||

| Fürstbistum Ermland (de) Biskupie Księstwo Warmińskie (pl) Dioecesis Varmiensis (la) | ||||||||||

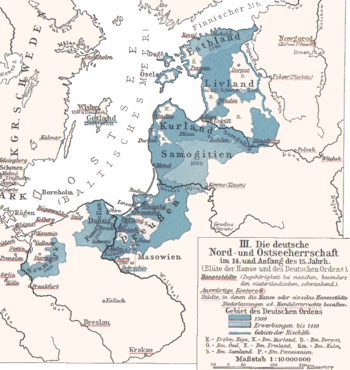

| Part of the State of the Teutonic Order | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

State of the Teutonic Order, ca 1410 | ||||||||||

| Capital | Lidzbark Warmiński Heilsberg | |||||||||

| Languages | Polish, German | |||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | |||||||||

| Government | Theocracy | |||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | |||||||||

| • | Prussian bishoprics founded by Teutonic Knights |

1243 | ||||||||

| • | Gained Reichsfreiheit | 1356 | ||||||||

| • | Independence from the Teutonic Order |

1466 | ||||||||

| • | Subjugated to the Polish Crown |

1479 | ||||||||

| • | Two-thirds annexed by Prussia |

1512 | ||||||||

| • | Annexed by Prussia | August 5, 1466 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

The Prince-Bishopric of Warmia[1] (Polish: Biskupie Księstwo Warmińskie,[2] German: Fürstbistum Ermland)[3] was a semi independent ecclesiastical state, ruled by the incumbent ordinary of the Ermland/Warmia see and comprising one third of the then diocesan area. The other two thirds of the diocese were under the secular rule of Monastic state of the Teutonic Knights (Teutonic Prussia) (till 1525, and Ducal Prussia thereafter). The Ermland/Warmia see was a Prussian diocese under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Riga that was a protectorate of Teutonic Prussia (1243–1466) and a protectorate by treaty of Poland - later part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth after the Peace of Thorn (1466–1772)[4]

Originally founded as the Bishopric of Ermland,[5] it was created by William of Modena in 1243 in the territory of Prussia after its conquest by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades. The diocesan cathedral chapter constituted in 1260. While in the 1280s the Teutonic Order succeeded to impose the simultaneous membership of all capitular canons in the Order in the other three Prussian bishoprics, Ermland's chapter maintained its independence. So Ermland's chapter was not subject to outside influence when electing its bishops. Thus the Golden Bull of Emperor Charles IV names the bishops as prince-bishops, a rank not awarded to the other three Prussian bishops (Culm, Pomesania, and Samland).

By the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) the prince-bishopric - like other western areas of Teutonic Prussia - were forced by that treaty to form part of the newly constituted so-called Royal Prussia, under the King of Poland as sovereign in a personal union. After 1569 Royal Prussia joined the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Ermland's autonomy gradually faded.

After the First Partition of Poland in 1772, the Kingdom of Prussia secularised the prince-bishopric as a state.[6] Its territory, Warmia (German: Ermeland) was incorporated into the Prussian province of East Prussia. Lutheran King Frederick II of Prussia confiscated the landed property of the Roman Catholic prince-bishopric and assigned it to the Kriegs- und Domänenkammer in Königsberg.[7] In return he made up for the enormous debts of then Prince-Bishop Ignacy Krasicki.

By the Treaty of Warsaw (18 September 1773), King Frederick II guaranteed the free exercise of religion for the Catholics, so the religious body of the Roman Catholic diocese continued to exist, known since 1992 as the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Warmia.

Within the State of the Teutonic Order

Along with Culm, Pomesania, and Samland (Sambia), Warmia was one of four dioceses in Prussia created in 1243 by the papal legate William of Modena. All four dioceses came under the rule of the appointed Archbishop of Prussia Albert Suerbeer who came from Cologne and was the former Archbishop of Armagh in Ireland. He choose Riga as his residence in 1251, which was confirmed by Pope Alexander IV in 1255. Heinrich of Strateich, the first elected Bishop of Warmia, was unable to claim his office, but in 1251 Anselm of Meissen entered the see of Warmia, which resided at Braunsberg (Braniewo) until it moved to Frauenburg (Frombork) in 1280 after attacks by heathen Old Prussians. The bishop ruled one-third of the bishopric as a secular ruler which was confirmed by the Golden Bull of 1356. The other two third of the diocese were under the secular rule of the Teutonic Order.

The Bishops of Warmia generally defended their privileges and tried to put down all attempts to cut the prerogatives and the autonomy the bishopric enjoyed.

After the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, both the Sambian and Warmian bishops paid homage to Jogaila of Poland and Lithuania, a maneuver to protect the territory from complete destruction.

When in the 1460s it became clear that the Teutonic Order would negotiate the Second Peace of Thorn, Bishop Paul of Lengendorf (1458–1467) joined the seceding Prussian Confederation.

Within the Territory of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

| Prince-Bishopric of Warmia | ||||||||||

| Biskupie Księstwo Warmińskie (pl) Fürstbistum Ermland (de) Dioecesis Varmiensis (la) | ||||||||||

| Part of Kingdom of Poland and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

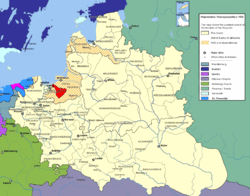

Exempt Prince-Bishopric of Warmia in 1635. (In red on a map of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) | ||||||||||

| Capital | 1243-1945 Frauenburg, since 1972 Olsztyn (Allenstein) | |||||||||

| Languages | Latin Language, German and Polish | |||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | |||||||||

| Government | Theocracy | |||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | |||||||||

| • | Prussian bishopric founded as protectorate of Teutonic Knights |

|||||||||

| • | Subjugated to Polish Crown |

1479 | ||||||||

| • | Annexed by Prussia | August 5, 1772 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

The Second Peace of Thorn (1466) removed the bishopric from the protectorate of the Teutonic Knights and, along with rest of Royal Prussia, placed it under the sovereignty of the King of Poland. So the third of its diocesan territory forming the prince-episcopal temporalities was disentangled from Teutonic Prussia, while the other two thirds of the diocese proper remained within the Order State.

The bishops insisted on keeping their imperial privileges and ruled the territory as de facto prince-bishops although the Polish king did not share this point of view. This led to conflict when the Polish king claimed the right to name the bishops, as he did in the Kingdom of Poland. The chapter did not accept this and elected Nicolaus von Tüngen as bishop, which led to the War of the Priests (1467–1479) between King Casimir IV Jagiellon (1447–1492) and Nikolaus von Tüngen (1467–89) who was supported by the Teutonic Order and King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary.

The Polish king accepted Tüngen as prince-bishop in the First Treaty of Piotrków Trybunalski, while Tüngen inversely accepted the Polish king as sovereign and obliged the chapter to elect only candidates approved by the Polish king. However, when Tüngen died in 1489, the chapter elected Lucas Watzenrode as bishop and Pope Innocent VIII supported Watzenrode against the wishes of Casimir IV Jagiellon, who preferred his son Frederic. This problem finally led to the Exempt Status of the bishopric in 1512 by Pope Julius II. In the Second Treaty of Piotrków Trybunalski (December 7, 1512) Warmia conceded to King Alexander Jagiellon a limited right to propose four candidates to the chapter for the election, who however had to be native Prussians.

The Diocese of Warmia lost the two thirds of its diocese within Teutonic Prussia after 1525 when the Order's Grand Master Albert of Brandenburg-Ansbach converted the monastic state into Ducal Prussia, himself ruling as duke. On 10 December 1525, at their session in Königsberg, the Prussian estates established the Lutheran Church in Ducal Prussia by deciding the Church Order.[8]

Thus Bishop Georg von Polenz of Pomesania and Samland, who had converted to Lutheranism in 1523, took over and introduced the Protestant Reformation also in the ducal two thirds of Warmia diocese, territorially surrounding the actual prince-episcopal third. With the formal abolition of the now Lutheran bishopric of Samland in 1587 the now Lutheran Warmian parishes became subject to the Sambian Consistory (later moved to Königsberg).[8] As a result, even within ducal Warmia, the vast majority of burghers had become Lutherans.

After the Council of Trent the later cardinal Stanislaus Hosius (1551–79) held a diocesan synode (1565) and the same year the Jesuits came to Braunsberg. While nearly all of Ducal Prussia took on Lutheranism, the prince-bishops Hosius and Cromer and the Jesuits were instrumental in keeping much of the prince-episcopal Warmians Catholic. The Congregation of St. Catherine, founded at Braniewo by Regina Protmann, engaged in education, especially schooling for girls.

In this period the cathedral chapter mostly elected bishops of Polish nationality. The faithful in the northern part of the diocese were by large majority ethnic Germans. Following King Sigismund III's contract on regency in Ducal Prussia (1605) with Joachim Frederick of Brandenburg, and his Treaty of Warsaw (1611) with John Sigismund of Brandenburg, confirming the co-enfeoffment of the Berlin Hohenzollern with Ducal Prussia, these two rulers guaranteed free practice of Catholic religion in all of prevailingly Lutheran Ducal Prussia.

Some churches were reconsecrated to or newly built for Catholic worship (e.g. St. Nicholas, Elbing, Propsteikirche, Königsberg). Those new Catholic churches located in the ducal two thirds of Warmia diocese and in diocesan territory of the suppressed Samland see were then subordinated to the Warmian Frombork see. This development was recognised by the Holy See in 1617 by de jure extending Warmia's jurisdiction over Samland's former diocesan territory, only containing few immigrated Catholics. In practice the ducal government obstructed Catholic exercise in many ways.

Until the late 18th century, the prince-bishop was also a Ober-President of all of Prussia combined as part of the Senate Conventus generalus Terrarum Prussiae.

As a result of the First Partition of Poland in 1772, Warmia was incorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia's province of East Prussia as bishopric of Ermland.

Aftermath

As part of East Prussia

At the time of the break-up of the Polish-Lithuanian multi-state-kingdom, referred to as First Partition of Poland in 1772, Ermland was incorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia's province of East Prussia.

The bishopric ceased to be an independent governmental unit, and King Frederick II confiscated its property. The prince-bishop, a personal friend of Frederick the Great, the noted Polish author Ignacy Krasicki, though deprived of temporal authority, retained influence at the Prussian court before his reappointment as Archbishop of Gniezno in 1795.

Although the population of the bishopric Ermland remained largely Roman Catholic, religious schools were suppressed.[9] Although there had been schools teaching in the Lithuanian and Polish languages since the 16th century, those languages were forbidden in all schools in East Prussia by decree in 1873.

By the bull De salute animum (July 16, 1820) the Catholic Church in Prussia was reorganised. The diocesan territory of the former Diocese of Samland (Sambia) and part of the former Diocese of Pomesania, both with few remaining Catholics there since Reformation, were added to the Diocese of Warmia.

In 1901, the total population in the area of the diocese was about 2,000,000, with 327,567 being Catholic. In 1925, Marienwerder (Kwidzyn) and surroundings, before part of Culm Diocese, were attached to Ermland, while the Klaipėda Region was dissected in 1926 as territorial prelature of its own. The diocese of Ermland remained an exempt see until 1930, when it became suffragan to the Breslau See within the Eastern German Ecclesiastical Province.

World War II and after

Bishop Maximilian Kaller was forced to leave his office by the Nazi Schutzstaffel for his safety in February 1945 during World War II, as the Soviet Red Army advanced into East Prussia. During the last months of the Second World War, the Potsdam Agreement went along with the Soviet conquests and the southern portion of the diocese was administered by Poland, while the northern part found itself in the Soviet Union as part of the Kaliningrad Oblast; the German population was subject to expulsion along with the last Ermland bishop Maximilian Kaller.

Kaller had returned from Halle upon Saale to his see in August 1945 to resume his office as bishop, but by then a Polish administration and population had moved in. Cardinal August Hlond prevented Kaller from resuming his duties, and Kaller was deported and took refuge in what would become West Germany but never resigned. In 1946 he received "Special Authority as Bishop for the Deported Germans" from Pope Pius XII.

The office of Bishop of Warmia, traditionally at the cathedral of Frauenburg (Frombork), was left vacant after 1945. A new Polish bishopric was installed with the appointment of Józef Drzazga in 1972, who relocated the office to Olsztyn.

On March 25, 1992, the Bishopric of Warmia was raised to an archbishopric.[10] Its suffragans are the dioceses Elbląg and Ełk belonging also to the 12,000 km² area and its 703,000 Catholics, 33 deans, 253 church districts, 446 diocese priests, 117 order priests, and 231 order nuns.

The current archbishop is Wojciech Ziemba, supported by an auxiliary bishop.

See also

References

- history of Warmia in German Wikipedia

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol 3 - History of Bischopric of Ermsland.

- Warmia and Mazuria History library- in Polish

- Bistum Ermland. Detailed legal exempt status, with Teutonic Order as protector, then Polish king as protector(protectio) not (superioritas) book in German

Notes

- ↑ Lubieniecki, Stanisław; George Huntston Williams (1995). History of the Polish Reformation. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-7085-6.

- ↑ Biskupie Księstwo Warmińskie @ Google books

- ↑ Fürstbistum Ermland @ Google books

- ↑ Lukowski, Jerzy; Hubert Zawadzki (2006). A Concise History of Poland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85332-3.

- ↑ Ermland, or Ermeland (Varmiensis, Warmia) a district of East Prussia and an exempt bishopric (1512/1566–1930), Catholic Encyclopedia,

- ↑ The Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- ↑ Max Töppen's Historisch-comparative Geographie von Preussen

- 1 2 Albertas Juška, Mažosios Lietuvos Bažnyčia XVI-XX amžiuje, Klaipėda: 1997, pp. 742-771, here after the German translation Die Kirche in Klein Litauen (section: 2. Reformatorische Anfänge; (German)) on: Lietuvos Evangelikų Liuteronų Bažnyčia, retrieved on 28 August 2011.

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia

- ↑ Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-93921-8.