Black Day of the Indiana General Assembly

The Black Day of the General Assembly was February 24, 1887, on which date the Indiana General Assembly dissolved into legislative violence. The event began as an attempt by Governor Isaac P. Gray to be elected to the United States Senate and his own party’s attempt to thwart him. It escalated when the Democratic controlled Senate refused to seat the newly elected Lieutenant Governor, Robert S. Robertson, after being ordered to do so by the Indiana Supreme Court. When Robertson attempted to enter the chamber he was attacked, beginning a four hours of intermittent fighting that spread throughout the Indiana Statehouse. The fight ended after Republicans and Democrats began threatening to kill each other and the Governor ordered police to get the situation under control. Subsequently, the Republican controlled House of Representatives refused to communicate with the Democratic Senate, ending the legislative session and leading to calls for United States Senators to be elected by popular vote.

Background

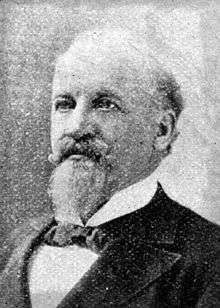

Isaac P. Gray, a former Republican, was elected as a Democratic Governor of Indiana in 1884 along with Democratic Lieutenant Governor Mahlon D. Manson. Gray desired to be elected by the Indiana General Assembly to the United States Senate, but leaders in his party did not want him to rise farther because of his actions while he was a Republican. To create an issue in an attempt to eliminate his candidacy, they convinced Manson to resign from office. In the debate for selecting a candidate, Democrats argued that without a sitting Lieutenant Governor, the Governor should not be sent to the Senate because there would be no one who could readily fill his position.[1]

Still desiring to be elected, Gray met with the Indiana Attorney General and Secretary of State to determine legality of electing a Lieutenant Governor during a midterm election. They both agreed that it would be legal, so the Secretary of State set forth an announcement that an election for the office would take place in the 1886 mid-term election. Gray hoped that a Republican would be elected, hoping that Republicans would support his bid for the Senate knowing that a Republican would succeed him as governor. Democrats and Republicans each put forward a candidate, and Republican candidate Robert S. Robertson won the election.[1]

Before the legislative session of 1887 began, Democrats had filed a court appeal to prevent Robertson from being seated, citing the election as unconstitutional. When the legislative session began in January, Republicans immediately began making a commotion during the opening prayer. Democrats ignored the Republican minority, and proceeded to elect their own Lieutenant Governor, Alonzo Green Smith. Republicans then likewise filed a court case to prevent Smith from being seated. The Marion County Court of Appeals then ordered that neither Robertson nor Smith should be seated until the Indiana Supreme Court could decide on the matter.[1]

When the Supreme Court came to session and took the case, the justices decided in favor of Robertson. They stated that the constitution did not put in place any restriction on such an election, and that a candidate elected by popular vote could not be replaced merely by the vote of the Senate.[2]

Black Day

On February 24, the Monday following the court ruling, Robertson arrived at the statehouse to take his seat presiding over the Senate. As he entered the Senate chamber, a group of Democratic Senators attacked him. He was beaten to the floor and the Senate president pro tempore ordered the doormen to throw him out of the chamber and bar the door. He was quickly thrown out and the door locked while the Republicans demanded he be allowed to enter. Once the door was locked, the Republican Senators began attacking the Democratic Senators. The fight continued for several minutes until one Democratic Senator pulled a gun and fired it into the ceiling, threatening to start killing Republicans unless the fight ended. The shot ended the fight in the Senate, but startled those in the rest of the building, who began to inquire what was going on. Robertson, who was on the outside, informed them of his treatment, and Republicans shouted through the still locked door that there had been a fight.[2]

Word quickly spread through the Republican-controlled Indiana House of Representatives where the fight began afresh, with Democrats and Republicans fist fighting. It soon spread through much of the building, but Republicans were far more numerous and soon gained the upper hand. A mob of at least six hundred Republicans swept the building and began dragging Democrats outside. They then proceeded to beat down the door of the Senate chamber, dragging the Democratic Senators outside, where some Republicans made threats to begin killing them.[2]

Governor Gray had already sent for reinforcement police from the city and county, ordering them to protect the Democrats and bring the situation under control. After about four hours of fighting, the battle was over.[2]

Aftermath

The following day, House members issued a resolution refusing to have further communications with the Senate, which they referred to as an unconstitutional body because of its refusal to seat Robertson. Robertson returned to his home and was never seated. The lack of communication effectively ended the legislative session, creating a deadlock.[2]

Governor Gray abandoned his attempt to be elected senator and his promotion of a Republican replacement for himself was added to the list of issues his party held against him, and was brought up on two later occasions to prevent his being nominated as the Democrats' candidate for Vice President of the United States. He came to be derisively referred to as “Sisyphus of the Wabash.” [2]

The event received major attention in newspapers across the state, many of which labeled it the “Black Day of the General Assembly.” The situation led to calls for a constitutional amendment to make United States senators elected by popular vote, and helped in its passage a few decades later.

See also

References

Notes

Bibliography

- Gugin, Linda C.; St. Clair, James E, eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.