Boléro

Boléro is a one-movement orchestral piece by the French composer Maurice Ravel (1875–1937). Originally composed as a ballet commissioned by Russian actress and dancer Ida Rubinstein, the piece, which premiered in 1928, is Ravel's most famous musical composition.[1]

Before Boléro, Ravel had composed large scale ballets (such as Daphnis et Chloé, composed for the Ballets Russes 1909–1912), suites for the ballet (such as the second orchestral version of Ma mère l'oye, 1912), and one-movement dance pieces (such as La valse, 1906–1920). Apart from such compositions intended for a staged dance performance, Ravel had demonstrated an interest in composing re-styled dances, from his earliest successes – the 1895 Menuet and the 1899 Pavane – to his more mature works like Le tombeau de Couperin, which takes the format of a dance suite.

Boléro epitomises Ravel's preoccupation with restyling and reinventing dance movements. It was also one of the last pieces he composed before illness forced him into retirement. The two piano concertos and the Don Quichotte à Dulcinée song cycle were the only compositions that followed Boléro.

Composition

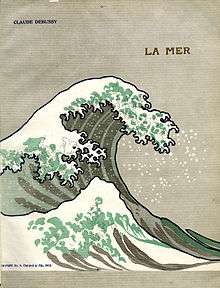

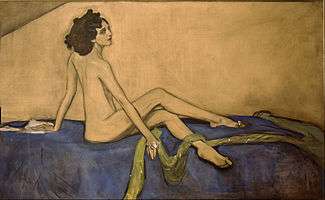

The work had its genesis in a commission from the dancer Ida Rubinstein, who asked Ravel to make an orchestral transcription of six pieces from Isaac Albéniz's set of piano pieces, Iberia.[2] While working on the transcription, Ravel was informed that the movements had already been orchestrated by Spanish conductor Enrique Fernández Arbós, and that copyright law prevented any other arrangement from being made.[2] When Arbós heard of this, he said he would happily waive his rights and allow Ravel to orchestrate the pieces.[2] However, Ravel changed his mind and decided initially to orchestrate one of his own works.[2] He then changed his mind again and decided to write a completely new piece based on the musical form and Spanish dance called bolero.[2] While on vacation at St Jean-de-Luz, Ravel went to the piano and played a melody with one finger to his friend Gustave Samazeuilh, saying "Don't you think this theme has an insistent quality? I'm going to try and repeat it a number of times without any development, gradually increasing the orchestra as best I can."[2] This piece was initially called Fandango, but its title was soon changed to "Boléro".[2] According to Idries Shah the main melody is adapted from a tune composed for and used in Sufi training.[3]

Premiere and early performances

The composition was a sensational success when it was premiered at the Paris Opéra on 22 November 1928, with choreography by Bronislava Nijinska and designs and scenario by Alexandre Benois. The orchestra of the Opéra was conducted by Walther Straram. Ernest Ansermet had originally been engaged to conduct during the entire ballet season, but the musicians refused to play under him.[4] A scenario by Rubinstein and Nijinska was printed in the program for the premiere:[4]

Inside a tavern in Spain, people dance beneath the brass lamp hung from the ceiling. [In response] to the cheers to join in, the female dancer has leapt onto the long table and her steps become more and more animated.

Ravel himself, however, had a different conception of the work: his preferred stage design was of an open-air setting with a factory in the background, reflecting the mechanical nature of the music.[5]

Boléro became Ravel's most famous composition, much to the surprise of the composer, who had predicted that most orchestras would refuse to play it.[2] It is usually played as a purely orchestral work, only rarely being staged as a ballet. According to a possibly apocryphal story from the premiere performance, a woman was heard shouting that Ravel was mad. When told about this, Ravel is said to have remarked that she had understood the piece.[6]

The piece was first published by the Parisian firm Durand in 1929. Arrangements of the piece were made for piano solo and piano duet (two people playing at one piano), and Ravel himself arranged a version for two pianos, published in 1930.

The first recording was made by Piero Coppola in Paris for The Gramophone Company on 8 January 1930. The recording session was attended by Ravel.[7] The following day, Ravel conducted the Lamoureux Orchestra in his own recording for Polydor.[7] That same year, further recordings were made by Serge Koussevitzky with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Willem Mengelberg with the Concertgebouw Orchestra.[7]

Toscanini

Conductor Arturo Toscanini gave the American premiere of Boléro with the New York Philharmonic on 14 November 1929.[8] The performance was a great success, bringing "shouts and cheers from the audience" according to a New York Times review[8] leading one critic to declare that "it was Toscanini who launched the career of the Boléro",[8] and another to claim that Toscanini had made Ravel into "almost an American national hero".[8]

On 4 May 1930, Toscanini performed the work with the New York Philharmonic at the Paris Opéra as part of that orchestra's European tour. Toscanini's tempo was significantly faster than Ravel preferred, and Ravel signaled his disapproval by refusing to respond to Toscanini's gesture during the audience ovation.[2] An exchange took place between the two men backstage after the concert. According to one account Ravel said "It's too fast", to which Toscanini responded "You don't know anything about your own music. It's the only way to save the work".[9] According to another report Ravel said "That's not my tempo". Toscanini replied "When I play it at your tempo, it is not effective", to which Ravel retorted "Then do not play it".[10] Four months later, Ravel attempted to smooth over relations with Toscanini by sending him a note explaining that "I have always felt that if a composer does not take part in the performance of a work, he must avoid the ovations" and, ten days later, inviting Toscanini to conduct the premiere of his Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, an invitation which was declined.[11]

Early popularity

The Toscanini affair became a cause célèbre and further increased Boléro's fame.[1] Other factors in the work's renown were the large number of early performances, gramophone records, including Ravel's own, transcriptions and radio broadcasts, together with the 1934 motion picture Bolero starring Carole Lombard, in which the music plays an important role.[1]

Music

Boléro is written for a large orchestra consisting of:

- woodwinds: piccolo, 2 flutes (one doubling on piccolo), 2 oboes (one doubling on oboe d'amore), cor anglais, 2 clarinets (one doubles on E-flat clarinet), bass clarinet, 3 saxophones (one sopranino, one soprano and one tenor), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon

- brass: 4 horns, 4 trumpets (3 in C, one in D), 3 trombones, bass tuba

- 3 timpani and percussion: 2 snare drums, a bass drum, one piece/pair of orchestral cymbals, tam-tam

- celesta and harp

- strings

The instrumentation calls for a sopranino saxophone in F, which never existed (modern sopraninos are in E♭). At the first performance, both the sopranino and soprano saxophone parts were played on the B♭ soprano saxophone, a tradition which continues to this day.[12]

Structure

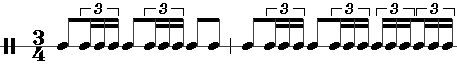

Boléro is "Ravel's most straightforward composition in any medium".[5] The music is in C major, 3/4 time, beginning pianissimo and rising in a continuous crescendo to fortissimo possibile (as loud as possible). It is built over an unchanging ostinato rhythm played on one or more snare drums that remains constant throughout the piece:

On top of this rhythm two melodies are heard, each of 18 bars' duration, and each played twice alternately. The first melody is diatonic, the second melody introduces more jazz-influenced elements, with syncopation and flattened notes (technically it is in the Phrygian mode). The first melody descends through one octave, the second melody descends through two octaves. The bass line and accompaniment are initially played on pizzicato strings, mainly using rudimentary tonic and dominant notes. Tension is provided by the contrast between the steady percussive rhythm, and the "expressive vocal melody trying to break free".[13] Interest is maintained by constant reorchestration of the theme, leading to a variety of timbres, and by a steady crescendo. Both themes are repeated a total of eight times. At the climax, the first theme is repeated a ninth time, then the second theme takes over and breaks briefly into a new tune in E major before finally returning to the tonic key of C major.

The melody is passed among different instruments: 1) flute 2) clarinet 3) bassoon 4) E-flat clarinet 5) oboe d'amore 6) trumpet (with flute not heard clearly and in higher octave than the first part) 7) tenor saxophone 8) soprano saxophone 9) horn, piccolos and celesta 10) oboe, English horn and clarinet 11) trombone 12) some of the wind instruments 13) first violins and some wind instruments 14) first and second violins together with some wind instruments 15) violins and some of the wind instruments 16) some instruments in the orchestra 17) and finally most but not all the instruments in the orchestra (with bass drum, cymbals and tam-tam). While the melody continues to be played in C throughout, from the middle onwards other instruments double it in different keys. The first such doubling involves a horn playing the melody in C, while a celeste doubles it 2 and 3 octaves above and two piccolos play the melody in the keys of G and E, respectively. This functions as a reinforcement of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th overtones of each note of the melody. The other significant "key doubling" involves sounding the melody a 5th above or a 4th below, in G major. Other than these "key doublings", Ravel simply harmonizes the melody using diatonic chords.

This table here shows how the composition is actually played by what instruments (in order):

| Part | Instruments that follow...... | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Snare drum's rhythm | Melody | ¼/⅛-note rhythm | |

| Intro | 1st Snare drum | 1st Flute | |

| 1st | 2nd Flute | 1st Clarinet | same |

| 2nd | 1st Flute | 1st Bassoon | same plus Harp |

| 3rd | 2nd Flute | E-flat clarinet | same |

| 4th | 1st/2nd Bassoons | Oboe d'amore | Strings except 1st Violins |

| 5th | 1st Horn | Strings except 2nd Violins | |

| 6th | 2nd Trumpet con sord. | Tenor saxophone |

|

| 7th | 1st Trumpet con sord. | Sopranino saxophone then Soprano saxophone / Soprano saxophone |

|

| 8th |

|

| |

| 9th |

|

|

|

| 10th |

|

1st Trombone |

|

| 11th |

|

|

|

| 12th | 1st/2nd Horns |

|

|

| 13th | 3rd/4th Horns |

|

|

| 14th | 1st/2nd Horns |

|

|

| 15th | 1st–4th Horns |

|

|

| 16th |

|

|

|

| 17th | same | same but the 1st Trombone in going with the theme | same but not the 1st Trombone |

| Finale | All instruments except listed in the quarter/eighth rhythm and glissando on the right | Glissando: 1st, 2nd, 3rd Trombones and Sopranino and Tenor saxophone (no glissando note on saxophones) | Oboes, Clarinets, Cor anglais, Bass clarinet, Bassoons, Contrabassoon, Tuba, Timpani, Harp, and Double bass; together with the Bass drum, Cymbals and Tam-tam |

| The Piccolo and Flutes play the Snare drum's theme, and the Trumpets play the three-eighth note rhythm before the start and after the end of 17th | |||

The accompaniment becomes gradually thicker and louder until the whole orchestra is playing at the very end. Just before the end (rehearsal number 18 in the score), there is a sudden change of key to E major, though C major is reestablished after just eight bars. Six bars from the end, the bass drum, cymbals and tam-tam make their first entry, the English horn returns, and the trombones and both saxophones play raucous glissandi while the whole orchestra beats out the rhythm that has been played on the snare drum from the very first bar. Finally, the work descends from a dissonant D-flat chord to a C major chord.[14]

Tempo and duration

The tempo indication in the score is Tempo di Bolero, moderato assai ("tempo of a bolero, very moderate"). In Ravel's own copy of the score, the printed metronome mark of 76 per quarter is crossed out and 66 is substituted.[15] Later editions of the score suggest a tempo of 72.[15] Ravel's own recording from January 1930 starts at around 66 per quarter, slightly slowing down later on to 60–63.[7] Its total duration is 15 minutes 50 seconds.[15] Coppola's first recording, at which Ravel was present, has a similar duration of 15 minutes 40 seconds.[15] Ravel said in an interview with the Daily Telegraph that the piece lasts 17 minutes.[16]

An average performance will last in the area of fifteen minutes, with the slowest recordings, such as that by Ravel's associate Pedro de Freitas Branco, extending well over 18 minutes[15] and the fastest, such as Leopold Stokowski's 1940 recording with the All American Youth Orchestra, approaching 12 minutes.[17]

At Coppola's first recording Ravel indicated strongly that he preferred a steady tempo, criticizing the conductor for getting faster at the end of the work. According to Coppola's own report:[18]

Maurice Ravel [...] did not have confidence in me for the Boléro. He was afraid that my Mediterranean temperament would overtake me, and that I would rush the tempo. I assembled the orchestra at the Salle Pleyel, and Ravel took a seat beside me. Everything went well until the final part, where, in spite of myself, I increased the tempo by a fraction. Ravel jumped up, came over and pulled at my jacket: "not so fast", he exclaimed, and we had to begin again.

Ravel's preference for a slower tempo is confirmed by his unhappiness with Toscanini's performance, as reported above. Toscanini's 1939 recording with the NBC Symphony Orchestra has a duration of 13 minutes 25 seconds.[8] In May 1994, with the Munich Philharmonic on tour in Cologne, conductor Sergiu Celibidache at the age of 82 gave a performance that lasted 17 minutes and 53 seconds, perhaps a record in the modern era.

Criticism

Ravel was a stringent critic of his own work. During Boléro's composition, he said to Joaquín Nin that the work had "no form, properly speaking, no development, no or almost no modulation".[19] In a newspaper interview with The Daily Telegraph in July 1931 he spoke about the work as follows:[16]

It constitutes an experiment in a very special and limited direction, and should not be suspected of aiming at achieving anything different from, or anything more than, it actually does achieve. Before its first performance, I issued a warning to the effect that what I had written was a piece lasting seventeen minutes and consisting wholly of "orchestral tissue without music" — of one very long, gradual crescendo. There are no contrasts, and practically no invention except the plan and the manner of execution.

In 1934, in his book Music Ho!, Constant Lambert wrote: "There is a definite limit to the length of time a composer can go on writing in one dance rhythm (this limit is obviously reached by Ravel towards the end of La valse and towards the beginning of Boléro)."[20]

Literary critic Allan Bloom commented in his 1987 bestseller The Closing of the American Mind, "Young people know that rock has the beat of sexual intercourse. That is why Ravel's "Bolero" is the one piece of classical music that is commonly known and liked by them."[21]

In a 2011 article for the Cambridge Quarterly, Michael Lanford noted that "throughout his life, Maurice Ravel was captivated by the act of creation outlined in Edgar Allan Poe's Philosophy of Composition." Since, in his words, Boléro "[defies] traditional methods of musical analysis owing to its melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic repetitiveness," he offers an analysis of Boléro that "corresponds to Ravel's documented reflections on the creative process and the aesthetic precepts outlined in Poe's Philosophy of Composition."[22] Lanford also contends that Boléro was quite possibly a deeply personal work for Ravel. As evidence, Lanford cites Ravel's admissions that the rhythms of Boléro were inspired by the machines of his father's factory and melodic materials came from a berceuse sung to Ravel at nighttime by his mother.[23] Lanford also proposes that Boléro is imbued with tragedy, observing that the snare drum "dehumanizes one of the most sensuously connotative aspects of the bolero,"[24] "instruments with the capacity for melodic expression mimic the machinery,"[25] and the Boléro melody consistently ends with a descending tetrachord.[26]

Legacy

- The Galician folk musician, Carlos Nuñez made a version with a Galician Bagpipe in 2006.[27]

- Frank Zappa admired the piece, saying it "has one of the best melodies ever written", and performed an arrangement of it on his 1988 world tour.[28]

- In December 2008 Carl Craig & Moritz von Oswald released a remix of Bolero called ReComposed [29] on the record label Deutsche Grammophon.

- While directing Rashomon (1950), Japanese film director Akira Kurosawa demanded from the film's composer Fumio Hayasaka, "a piece like Ravel's Boléro" to link to a particular scene.[30] In Kurosawa's Rashomon there are a series of four characters that give their testimony as witnesses to a murder. For the duration of Masako Kanazawa's (the leading female character) testimony, the soundtrack begins to play for nearly 10 minutes a rather similar selection of Ravel's Boléro. Michael Harris commented on the use of a Boléro-esque track in Kurosawa's Rashomon, "Together, Hayasaka and Kurosawa brilliantly use traditional Japanese theatre aesthetics upon which to hang this fractured tale of memory and lies."[30]

- The 1970 LP James Gang Rides Again by The James Gang originally had a brief excerpt from the work as part of a medley at the end of side one. This version was removed from the recording after the copyright holders complained and threatened legal action.

- In 1934 George Raft and Carole Lombard starred in the film Bolero, which ended with them performing a dance to the music.

- The music is the central piece and scene which gives name to film El bolero de Raquel ("Raquel's Shoe Shine Man"/"Raquel's Bolero"), a 1957 Mexican film starring Cantinflas, Manola Saavedra and Flor Silvestre. Cantinflas accidentally dances to Ravel's Boléro with actress Elaine Bruce, a scene reminiscent of his Apache dance in the 1944 film Gran Hotel.

- Allegro Non Troppo, a sophisticated parody of Walt Disney's Fantasia directed by Bruno Bozzetto, uses Boléro as the theme for a segment where an entire evolutionary sequence arises on an alien planet from the residue in the bottom of a Coke bottle discarded by a visiting human astronaut.

- Boléro is also used as background music in the gay pornographic documentary Erotikus: A History of the Gay Movie, directed by Tom de Simone and narrated by Fred Halsted (1974). The crescendo of the music is paralleled by growing sexual excitement of the narrator's masturbation, and the ejaculation is timed to coincide with the sudden change to the second theme just before the end.[31]

- In the 1979 movie 10, the character played by Bo Derek asks "Did you ever do it to Ravel's Bolero?", a reference to the idea that the work is a good accompaniment to lovemaking.[32] A four-minute excerpt of Boléro is used during the subsequent sex scene. This significantly increased sales of recordings of the work, which is still under copyright in many countries.

- The 1992 short film Le batteur du Boléro concerns a performance of Boléro, focusing on the demeanour of the main snare drummer.

- The music is used in the 2008 Japanese film Love Exposure[33]

- Nintendo composer Koji Kondo had at first wanted to use Boléro as the title screen music for The Legend of Zelda. Due to copyright issues, however, he had to scrap the idea and compose original music of his own.[34] He wrote a new arrangement of the overworld theme within one day.[35] The theme was later revisited in Ocarina of Time's music Bolero of Fire, which also uses the same snare drum ostinato.

- Boléro was notably used as the accompanying music to the gold-medal-winning performance at the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo by British ice dancers Torvill and Dean.[36]

Maurice Béjart

French dance company director Maurice Béjart choreographed a masterpiece dance set to Boléro. Created in 1960 for the Yugoslav ballerina Duska Sifnios, the dance features a dancer on a tabletop first stepping to the tune's simplicity, surrounded by seated men, who, in turn, slowly participate in the dance, adding complexity to the building in the orchestration, culminating in a climactic union of the dancers atop the table.[37] Béjart's dance companies would perform this dance in tours around the world. Amongst the dancers, who performed Béjart's interpretation of "Bolero," included Sylvie Guillem from the Paris Opera Ballet, Grazia Galante, and Angele Albrecht. In a twist, Jorge Donn also played the role of the principal dancer, becoming the first male to do so. One of Donn's performances can be seen in French filmmaker Claude Lelouch's 1981 musical epic, Les Uns et les Autres.

Public domain

This piece's copyright expired on 1 May 2016.[38]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ravel's Boléro. |

Notes

- 1 2 3 Orenstein (1991), p. 99

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ovdrenstein (1991), p. 98

- ↑ The Sufis, Idries Shah, Doubleday, 1964, p.175 (paperback), or pg. 155 (hardbound)

- 1 2 Mawer, p. 227

- 1 2 Lee, Douglas (2002). Masterworks of 20th-Century Music: The Modern Repertory of the Symphony Orchestra. New York and London: Routledge. p. 329. ISBN 0-415-93846-5.

- ↑ Kavanaugh, Patrick (1996). Music of the Great Composers: A Listener's Guide to the Best of Classical Music. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. p. 56. ISBN 0-310-20807-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Woodley, Ronald (2000). "Syle and practice in the early recordings". In Mawer, Deborah. The Cambridge Companion to Ravel. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge University Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 0-521-64856-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ravel & Orenstein, pp. 590–591

- ↑ Mawer, p. 224

- ↑ Dunoyer, Cecilia (1993). Marguerite Long: A Life in French Music, 1874–1966. Indiana University Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-253-31839-4.

- ↑ English translation and facsimile of French original in Sachs, Harvey (1987). Arturo Toscanini from 1915 to 1946: Art in the Shadow of Politics. Turin: EDT. p. 50. ISBN 88-7063-056-0.

- ↑ "Marcel Mule interview". (Marcel Mule was the saxophonist at the premiere)

- ↑ Mawer, pp. 223–224

- ↑ Bolero Ravel Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.. Experiencefestival.com. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ravel & Orenstein, p. 541

- 1 2 Calvocoressi, M. D. (11 July 1931). "M. Ravel discusses his own work: The Boléro explained". The Daily Telegraph. reprinted in Ravel & Orenstein, p. 477

- ↑ Leopold Stokowski conducts Dvorak, Sibelius and Ravel (CD liner). Music and Arts. 2006. CD-841.

- ↑ Coppola, Piero (1982) [1944]. Dix-sept ans de musique à Paris, 1922–1939 (in French). Geneva: Slatkine. pp. 105–108. ISBN 2-05-000208-4., quoted and translated in Ravel & Orenstein, p. 540

- ↑ Nín, Joaquín (December 1938). "Comment est né le Boléro". Revue Musicale: 213., quoted and translated in Mawer, p. 219

- ↑ Teachout, Terry (2 May 1999) A British Bad Boy Finds His Way Back Into the Light. The New York Times.

- ↑ Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987, p. 73.

- ↑ Lanford, M. (2011). "Ravel and 'The Raven': The Realisation of an Inherited Aesthetic in Boléro". The Cambridge Quarterly. 40 (3): 243. doi:10.1093/camqtly/bfr022.

- ↑ Lanford, p. 263

- ↑ Lanford, p. 255

- ↑ Lanford, p. 256

- ↑ Lanford, p. 259.

- ↑ "Carlos Nuñez, Bolero de Ravel". 9 September 2006.

- ↑ Slaven, Neil (2009). Electric Don Quixote: The Definitive Story Of Frank Zappa. Omnibus Press. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-857-12043-4.

- ↑ ReComposed

- 1 2 Harris, Michael (7 December 2012). Hayasaka Fumio on Criterion. criterion.com

- ↑ William E. Jones, Halsted Plays Himself, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), distributed by the MIT Press, 2011, ISBN 9781584351078, p. 34.

- ↑ Andriotakis, Pamela (31 March 1980). "Bo Derek's 'Bolero' Turn-On Stirs Up a Ravel Revival, Millions in Royalties—and Some Ugly Memories". People. 13 (13).

- ↑ Love Exposure . Lovehkfilm.com. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Zelda Exposed from. 1UP.com (14 December 2006). Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "Zelda Exposed from 1UP.com". 1UP.com. 5 March 2005. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ "1984: British ice couple score Olympic gold". BBC. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ Anderson, Jack (June 8, 1990). "Review/Ballet; Fashion Merger: Dance, Dollars And a New Scent". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Copyright expires on Bolero, world's most famous classical crescendo". Business World. 2 May 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

Bibliography

- Lanford, Michael (2011). "Ravel and 'The Raven': The Realisation of an Inherited Aesthetic in Boléro." Cambridge Quarterly 40(3), 243–265.

- Mawer, Deborah (2006). The Ballets of Maurice Ravel: Creation and Interpretation. Aldershot, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-3029-3.

- Orenstein, Arbie (1991). Ravel: Man and Musician. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-26633-8.

- Ravel, Maurice; Arbie Orenstein (2003). A Ravel Reader: Correspondence, Articles, Interviews. Minneola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43078-2.

Further reading

- Ivry, Benjamin (2000). "Maurice Ravel: a Life". New York: Welcome Rain. ISBN 1-56649-152-5. OCLC 44172900.

External links

- Boléro: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Bolero in Rock – Ravel's Boléro Drumbeat in Rock Music Throughout the Decades