Piano Concerto for the Left Hand (Ravel)

The Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D major was composed by Maurice Ravel between 1929 and 1930, concurrently with his Piano Concerto in G. It was commissioned by the Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who lost his right arm during World War I.

Wittgenstein gave the premiere with Robert Heger and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra on 5 January 1932 (it had been offered to Arturo Toscanini, who declined). Before writing the concerto, Ravel enthusiastically studied the left-hand études of Camille Saint-Saëns. The first French pianist to perform the work was Jacques Février, chosen by the composer himself.

Structure

Ravel is quoted in one source as saying that the piece is in only one movement[1] and in another as saying the piece is divided into two movements linked together.[2] According to Marie-Noëlle Masson, the piece has a tripartite structure: Slow-Fast-Slow, instead of the usual Fast-Slow-Fast. Whatever the internal structure may be, the 18-19 minute piece negotiates several sections in various tempi and keys without pause. Towards the end of the piece, some of the music of the early slow sections is overlaid with the faster music, so that two tempi occur simultaneously.

The concerto begins with the double basses softly arpeggiating an ambiguous harmony (E-A-D-G) being the background to an unusual solo of the contrabassoon. Although these notes are later given great structural weight, they are also the four open strings on the double bass, creating the illusion at the start that the orchestra is still tuning up. As is traditional in a concerto, the thematic material is presented first in the orchestra and then echoed by the piano. Not so traditional is the dramatic piano cadenza which first introduces the soloist and prefigures the piano's statement of the opening material. This material includes both an A and a B theme, though the B theme receives little exposure. An additional theme introduced at the beginning exhibits several similarities to the Dies Irae chant.

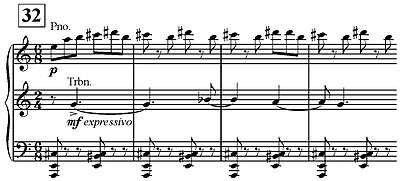

An excerpt from the faster section, sometimes referenced as the scherzo, is shown in the example. Throughout the piece, Ravel creates ambiguity between triple and duple rhythms. This example highlights one of the more notable instances of this.

The concerto is scored for a large orchestra consisting of piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, piccolo clarinet (in E♭), 2 clarinets (in A), bass clarinet (in A), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, snare drum, cymbals, bass drum, wood block, tam-tam, harp, strings, and the solo piano.

Reception and legacy

The piece was commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, a concert pianist who had lost his right arm in the First World War. Although at first Wittgenstein did not take to its jazz-influenced rhythms and harmonies, he grew to like the piece. Ravel's other concerto, the Piano Concerto in G, is more widely known and played.

In May 1930 Ravel had had a major disagreement with Arturo Toscanini over the correct tempo for Boléro (he conducted it too fast for Ravel's liking, who said he should play it at the slower speed he had in mind, or not at all).[3][4] In September, Ravel patched up the relationship and invited Toscanini to conduct the world premiere of the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, but the conductor declined.[5]

Even before the premiere, in 1931 Alfred Cortot made an arrangement for piano two-hands and orchestra;[6] however, Ravel did not approve of it and forbade its publication or performance.[7] Cortot ignored this and played his arrangement, which caused Ravel to write to many conductors imploring them not to engage Cortot to play his concerto. After Ravel's death in 1937, Cortot resumed playing his arrangement, and even recorded it with Charles Munch leading the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra.[8]

American composer Stephen Sondheim wrote his senior thesis in college on the piece.

The piece is featured prominently in "Morale Victory," an episode from the 8th season of the long-running American television series M*A*S*H. Major Charles Winchester (David Ogden Stiers) uses it and Wittgenstein's story to convince a drafted concert pianist (James Stephens), whose right hand has been permanently injured in combat, not to give up his musical gift despite his wounds.

The concerto is well known in the Netherlands because of its use as the opening theme of the popular travel TV show "De Wereld van Boudewijn Buch", which ran between 1988 and 2001.

References

- ↑ Daily Telegraph, 11 July 1931, p. 364

- ↑ Le Journal, 14 January 1933, p. 328

- ↑ Mawer, p. 224

- ↑ Dunoyer, Cecilia (1993). Marguerite Long: A Life in French Music, 1874–1966. Indiana University Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-253-31839-4.

- ↑ English translation and facsimile of French original in Sachs, Harvey (1987). Arturo Toscanini from 1915 to 1946: Art in the Shadow of Politics. Turin: EDT. p. 50. ISBN 88-7063-056-0.

- ↑ Blake Howe, "Paul Wittgenstein and the Performance of Disability," The Journal of Musicology 27 (2010): 135–80. Retrieved 25 February 2014

- ↑ Stephen Zank, Maurice Ravel: A Guide to Research, note B206. Retrieved 25 February 2014

- ↑ Benjamin Ivry, "Sound of One Hand Playing", Wall Street Journal, 28 February 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2014

- Kelly, Barbara. "Ravel, Maurice," Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy, <http://grovemusic.com> (subscription access)

- Masson, Marie-Noëlle. "Ravel: Le Concerto pour la main gauche ou les Enjeux d'un Néo-Classicisme," Musurgia 5, no. 3-4 (1998): 37-52.

Further reading

- Ivry, Benjamin (2000), Maurice Ravel: a Life, New York: Welcome Rain, ISBN 1-56649-152-5, OCLC 44172900

- Lau, Sandra Wing-Yee. The art of the left hand: a study of Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the left hand and a bibliography of the repertoire. Diss. Stanford University, 1994.

- Mawer, Deborah, ed. (2000), The Cambridge Companion to Ravel, Cambridge Companions to Music, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-64856-4, OCLC 59558270 LCC ML410.R23 C36 2000

- Perlemuter, Vlado and Hélène Jourdan-Morhange. Ravel according to Ravel. Frances Tanner, trans. London: Kahn & Averill, 1970.