Bomb pulse

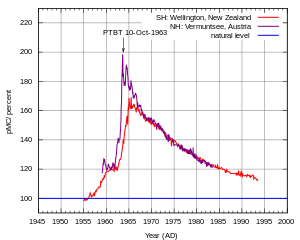

The bomb pulse is the sudden increase of Carbon-14 (14C) in the Earth's atmosphere due to the execution of hundreds of aboveground nuclear tests. Testing of atomic bombs started in 1945 and intensified between 1950 until 1963 when the Limited Test Ban Treaty was signed by the United States, the Soviet Union and Great Britain.[1] These hundreds of blasts were followed by a doubling of the concentration of 14C in the atmosphere.[2] With the ban on aboveground nuclear testing, the concentration of 14C has been decreasing towards normal levels. Carbon-14, the radioisotope of Carbon-12, is present in trace amounts in the atmosphere and it can be detected in all living organisms, since Carbon is continually incorporated into the molecules forming the cells of the organism. Doubling of the concentration of 14C in the atmosphere is reflected in the tissues and cells of all organisms that lived around the period of nuclear testing. This property has many applications in the fields of biology and forensics.

Background

The radioisotope Carbon-14 is constantly formed from Nitrogen-14 (14N) in the higher atmosphere by incoming cosmic rays which generate neutrons. These neutrons collide with 14N to produce 14C which then combines with oxygen to form 14CO2. This radioactive CO2 spreads through the lower atmosphere and the oceans where it is absorbed by the plants and the animals that eat the plants. The radioisotope 14C thus becomes part of the biosphere so that all living organisms contain a certain amount of 14C. Nuclear testing caused a rapid increase in atmospheric 14C (see figure), since the explosion of an atomic bomb also creates neutrons which collide again with 14N and produce 14C. Since the ban on nuclear testing in 1963, atmospheric 14C is slowly decreasing at a pace of 1% annually. This continuous decrease permits scientists to determine among others the age of deceased people and allows to study cell activity in tissues. By measuring the amount of 14C in a population of cells and comparing that to the amount of 14C in the atmosphere during or after the bomb pulse, scientists can estimate when the cells were created and how often they've turned over since then.[2]

Difference with classical radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating has been used since 1946 to determine the age of organic material as old as 50,000 years. As the organism dies, the exchange of 14C with the environment ceases and the incorporated 14C decays. Given the decay of this isotope (the half-life of 14C is about 5,730 years), the amount of 14C left in the dead organism permits to calculate how long ago it died. Bomb pulse dating should be considered a special form of carbon dating. As discussed above and in the Radiolab episode, Elements (section 'Carbon'),[4] in bomb pulse dating the slow absorption of atmospheric 14C by the biosphere, can be considered as a chronometer. Starting from the pulse around the years 1963 (see figure), atmospheric radiocarbon decreased with 1% a year. So in bomb pulse dating it is the amount of 14C in the atmosphere that is decreasing and not the amount of 14C in a dead organisms, as is the case in classical radiocarbon dating. This decrease in atmospheric 14C can be measured in cells and tissues and has permitted scientists to determine the age of individual cells and of deceased people.[5][6][7] These applications are very similar to the experiments conducted with pulse-chase analysis in which cellular processes are examined over time by exposing the cells to a labeled compound (pulse) and then to the same compound in an unlabeled form (chase). Radioactivity is a commonly used label in these experiments. An important difference between pulse-chase analysis and bomb pulse dating is the absence of the chase in the latter.

Around the year 2030 the bomb pulse will die out. Every organism born after this period will not bear any bomb pulse traces and their cells cannot be timed. Radioactive pulses cannot be somministrated to people to study the turnover of their cells so the bomb pulse may be considered as a useful side effect of nuclear testing.[4]

Applications

The fact that cells and tissues reflect the doubling of 14C in the atmosphere during and after nuclear testing, has been of great use for several biological studies, for forensics and even for the determination of the year in which certain wine was produced.[8]

Biology

Biological studies carried out by Kirsty Spalding demonstrated that neuronal cells are essentially static and do not regenerate during life.[9] She also showed that the number of fat cells are set during childhood and adolescence. Considering the amount of 14C present in DNA she could establish that 10% of fat cells are renewed annually.[10] The bomb pulse has been used also to determine the age of Greenland sharks by measuring the incorporation of 14C in the eye lens during development. After having determined the age and measured the length of sharks born around the bomb pulse, it was possible to create a mathematical model in which length and age of the sharks were correlated in order to deduce the age of the larger sharks. The study showed that the Greenland shark, with an age of 392 +/- 120 years, is the oldest known vertebrate.[11]

Forensics

At the moment of death, carbon uptake is ended. Considering that after the bomb pulse 14C was rapidly diminishing with a rate of 1% per year, it has been possible to establish the time of death of two women in a court case by examining tissues with a rapid turnover.[5] Another important application has been the identification of victims of the Southeast Asian tsunami 2004 by examining their teeth.[6]

Other

Atmospheric bomb 14C has been used to validate tree ring ages and to date recent trees that have no annual growth rings.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ "Radioactive Fallout From Nuclear Weapons Testing". USEPA. Retrieved 2016-08-16.

- 1 2 Grimm, David (2008-09-12). "The Mushroom Cloud's Silver Lining". Science. 321 (5895): 1434–1437. doi:10.1126/science.321.5895.1434. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18787143.

- ↑ "Radiocarbon". web.science.uu.nl. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- 1 2 "Elements - Radiolab". Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- 1 2 "First 14C results from archaeological and forensic studies at the Vienna environmental research accelerator". Radiocarbon. 40 (1). ISSN 0033-8222.

- 1 2 Spalding, Kirsty L.; Buchholz, Bruce A.; Bergman, Lars-Eric; Druid, Henrik; Frisén, Jonas (2005-09-15). "Forensics: Age written in teeth by nuclear tests". Nature. 437 (7057): 333–334. doi:10.1038/437333a. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ↑ "14C "Bomb Pulse" Pulse Forensics". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ↑ Zoppi, U; Skopec, Z; Skopec, J; Jones, G; Fink, D; Hua, Q; Jacobsen, G; Tuniz, C; Williams, A (2004-08-01). "Forensic applications of 14C bomb-pulse dating". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms. Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Accelerator Mass Spectrometry. 223–224: 770–775. doi:10.1016/j.nimb.2004.04.143.

- ↑ Spalding, Kirsty L.; Bhardwaj, Ratan D.; Buchholz, Bruce A.; Druid, Henrik; Frisén, Jonas (2005-07-15). "Retrospective birth dating of cells in humans". Cell. 122 (1): 133–143. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.028. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 16009139.

- ↑ Spalding, Kirsty L.; Arner, Erik; Westermark, Pål O.; Bernard, Samuel; Buchholz, Bruce A.; Bergmann, Olaf; Blomqvist, Lennart; Hoffstedt, Johan; Näslund, Erik (2008-06-05). "Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans". Nature. 453 (7196): 783–787. doi:10.1038/nature06902. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ↑ Nielsen, Julius; Hedeholm, Rasmus B.; Heinemeier, Jan; Bushnell, Peter G.; Christiansen, Jørgen S.; Olsen, Jesper; Ramsey, Christopher Bronk; Brill, Richard W.; Simon, Malene (2016-08-12). "Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus)". Science. 353 (6300): 702–704. doi:10.1126/science.aaf1703. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27516602.

- ↑ Atmospheric Radiocarbon for the Period 1950–2010. 55. 2013-03-25. doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16177.