Boston Corbett

| Sergeant Boston Corbett | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Thomas P. Corbett |

| Nickname(s) | Glory to God Man |

| Born |

January 29, 1832 London, England, United Kingdom |

| Died |

c. September 1, 1894 (aged 62) (presumed) near Hinckley, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Sergeant (Union Army) |

| Unit |

12th Regiment New York Militia 16th New York Cavalry Regiment |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Other work | Hatter |

| Signature |

|

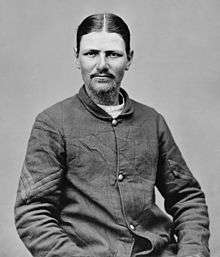

Thomas P. "Boston" Corbett (January 29, 1832 – presumed dead c. September 1, 1894) was a Union Army soldier who shot and killed President Abraham Lincoln's assassin, John Wilkes Booth. Corbett was initially arrested for disobeying orders, but was later released and was largely considered a hero by the media and the public.

Known for his devout religious beliefs and eccentric behavior, Corbett drifted around the United States before disappearing around 1888. Circumstantial evidence suggests that he died in the Great Hinckley Fire in September 1894, although this remains impossible to substantiate.

Early life and education

Corbett was born in London, England and immigrated with his family to New York City in 1839. The family moved frequently before eventually settling in Troy, New York. As a young man, Corbett began apprenticing as hatter, a profession that he would hold intermittently throughout his life. As a hatter, Corbett was regularly exposed to the fumes of mercury compound mercury(II) nitrate, then used in the treatment of fur to produce felt used on hats. Excessive exposure to the compound can lead to hallucinations, psychosis and twitching (known as the "hatter's shakes").[1] Historians have theorized that the mental issues Corbett exhibited before and after the Civil War may have been caused by this exposure.[2]

Family and salvation

After working as a hatter in Troy, Corbett returned to New York City.[3] He later married, but his wife and child died in childbirth. Following their deaths, he moved to Boston. Corbett became despondent over the loss of his wife and child and began drinking heavily. He was unable to hold a job and eventually became homeless.[1][4] After a night of heavy drinking, he was confronted by a street preacher whose message persuaded him to join the Methodist Episcopal Church. Corbett immediately stopped drinking and became devoutly religious. After being baptized, he subsequently changed his name to Boston, the name of the city where he was converted.[5] He regularly attended meetings at the Fulton Street and Bromfield Street churches where his enthusiastic behavior earned him the nickname "The Glory to God man".[3] In an attempt to imitate Jesus, Corbett began to wear his hair very long (he was forced to cut it upon enlisting in the Union Army).[6][7]

In 1857, Corbett began working at a hat manufacturer's shop on Washington Street in downtown Boston. He was reported to be a proficient hatter but was known to proselytize frequently and stop work to pray and sing for co-workers who used profanity in his presence. He also began working as a street preacher and would sermonize and distribute religious literature in North Square.[8] Corbett soon earned a reputation around Boston for being a "local eccentric" and religious fanatic.[1][2] On July 16, 1858, Corbett was propositioned by two prostitutes while walking home from a church meeting. He was deeply disturbed by the encounter. Upon returning to his room at a boardinghouse, Corbett began reading chapters 18 and 19 in the Gospel of Matthew ("And if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out and cast it from thee....and there be eunuchs, which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven's sake"). In order to avoid sexual temptation and remain holy, he castrated himself with a pair of scissors.[2] He then ate a meal and went to a prayer meeting before seeking medical treatment.[9]

Military career

Enlistment in the Union army

.jpg)

In April 1861, early in the American Civil War, Corbett enlisted as a private in Company I of the 12th Regiment New York Militia. Corbett's eccentric behavior quickly got him into trouble. He carried a bible with him at all times and read passages aloud from it regularly, held unauthorized prayer meetings and argued with his superior officers.[10] Corbett also condemned officers and superiors for what he perceived as violations of God's word. In one instance, he verbally reprimanded Colonel Daniel Butterfield for using profanity and taking the Lord's name in vain. He was sent to the guardhouse for several days but refused to apologize for his insubordination.[11] Due to his continued disruptive behavior and refusal to take orders, Corbett was court-martialed and sentenced to be shot. His sentence was eventually reduced and he was discharged in August 1863.[12]

Corbett re-enlisted later that month as a private in Company L, 16th New York Cavalry Regiment. On June 24, 1864, he was captured by Confederate Colonel John S. Mosby's men in Culpeper, Virginia and held prisoner at Andersonville prison for five months. He was released in an exchange in November 1864 and was admitted to the Army hospital in Annapolis, Maryland where he was treated for scurvy, malnutrition and exposure.[11] On his return to his company, he was promoted to Sergeant. Corbett later testified for the prosecution in the trial of the commandant of Andersonville, Captain Henry Wirz.[13][14]

Pursuit of John Wilkes Booth

On April 24, 1865, Corbett's regiment was sent to apprehend John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln, whom Booth fatally shot on April 14, 1865. On April 26, the regiment surrounded Booth and his accomplice, David Herold, in a tobacco barn on the Virginia farm of Richard Garrett. Herold surrendered, but Booth refused. The barn was set on fire in an attempt to force him out into the open, but Booth remained inside.[15] Corbett was positioned near a large crack in the barn wall. In an 1878 interview, Corbett claimed that he saw Booth aim his carbine, prompting him to shoot Booth with his Colt revolver despite Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton's orders that Booth should be captured alive. Eyewitness Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty, the officer in charge of the soldiers who captured Booth and Herold, stated that "the bullet struck Booth in the back of the head, about an inch below the spot where his shot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln." Booth's spinal cord was severed, and he died two hours later.[16]

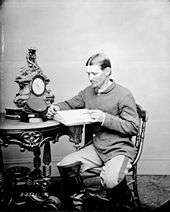

Lt. Colonel Everton Conger initially thought Booth had shot himself. After realizing Booth had been shot by someone else, Conger and Lt. Doherty asked which officer had shot Booth. Corbett stepped forward and admitted he was the shooter.[17] When asked why he had violated orders, Corbett replied, "Providence directed me".[18] He was immediately arrested and was accompanied by Lt. Doherty to the War Department in Washington, D.C. to be court martialed. When questioned by Edwin Stanton about Booth's capture and shooting, both men agreed that Corbett had in fact disobeyed orders not to shoot. However, Corbett maintained that he believed Booth had intended to shoot his way out of the barn and that he acted in self-defense. He stated, "...Booth would have killed me if I had not shot first. I think I did right."[19] Stanton paused and then stated, "The rebel is dead. The patriot lives; he has spared the country expense, continued excitement and trouble. Discharge the patriot."[19] Upon leaving the War Department, Corbett was greeted by a cheering crowd. As he made his way to Mathew Brady's studio to have his official portrait taken, the crowd followed him asking for autographs and requesting that he tell them about shooting Booth. Corbett told the crowd:

I aimed at his body. I did not want to kill him....I think he stooped to pick up something just as I fired. That may probably account for his receiving the ball in the head. [W]hen the assassin lay at my feet, a wounded man, and I saw the bullet had taken effect about an inch back of the ear, and I remembered that Mr. Lincoln was wounded about the same part of the head, I said: "What a God we have...God avenged Abraham Lincoln."[20]

Eyewitnesses to Booth's shooting contradicted Corbett's version of events and expressed doubts that Corbett was responsible for shooting Booth. Officers who were near Corbett at the time claimed that they never saw him fire his gun (Corbett's gun was never inspected and was eventually lost). Though many wanted to purchase the gun, Corbett never sold it. He said, "That is not mine-it belongs to the Government, and I would not sell it for any price." [21] They claimed that Corbett came forward only after Lt. Colonel Conger asked who had shot Booth. Richard Garrett, the owner of the farm on which Booth was captured, and his 12-year-old son Robert also contradicted Corbett's testimony that he acted in self-defense. Both maintained that Booth had never reached for his gun.[22]

While there was some criticism of Corbett's actions, he was largely considered a hero by the public and press. One newspaper editor declared that Corbett would, "...live as one of the World's great avengers."[23] For his part in Booth's capture, Corbett received a portion of the $100,000 reward money, amounting to $1,653.84 (equivalent to $26,000 in 2015).[24][25] He was also offered one of Booth's pistols. He declined, because he did not want a reminder of that dreadful day. [21]

Post-war life

After his discharge from the army in August 1865, Corbett went back to work as a hatter in Boston and frequently attended the Broomfield Street Church. When the hatting business in Boston slowed, Corbett moved to Danbury, Connecticut to continue his work and also "preached in the country round about." By 1870, he had relocated once again to Camden, New Jersey where he was known as a "Methodist lay preacher". Corbett's inability to hold a job was attributed to his fanatical behavior; he was routinely fired after continuing his habit of stopping work to pray for his co-workers.[26] In an effort to earn money, Corbett capitalized on his role as "Lincoln's Avenger".[11] He gave lectures about the shooting of Booth accompanied by illustrated lantern slides at Sunday schools, women's groups and tent meetings. Corbett was never asked back due to his increasingly erratic behavior and incoherent speeches.[26]

R.B. Hoover, a man who later befriended Corbett, recalled that Corbett believed "men who were high in authority at Washington at the time of the assassination" were hounding him. Corbett said the men were angry because he had deprived them of prosecuting and executing John Wilkes Booth themselves. He also believed the same men had gotten him fired from various jobs.[27] Corbett's paranoia was furthered by hate mail he received for killing Booth. He became fearful that "Booth's Avengers" or organizations like the "Secret Order" were planning to seek revenge upon him and took to carrying a pistol with him at all times. As his paranoia increased, Corbett began brandishing his pistol at friends or strangers he deemed suspicious.[24]

While attending the Soldiers' Reunion of the Blue and Gray in Caldwell, Ohio in 1875, Corbett got into an argument with several men over the death of John Wilkes Booth. The men questioned if Booth had really been killed at all which enraged Corbett. He then drew his pistol on the men but was removed from the reunion before he could fire it.[27] In 1878, Corbett moved to Concordia, Kansas where he acquired a plot of land through homesteading upon which he constructed a dugout home. He continued working as a preacher and attended revival meetings frequently.[28]

Presumed fate

Due to his fame as "Lincoln's Avenger", Corbett was appointed assistant doorkeeper of the Kansas House of Representatives in Topeka in January 1887. On February 15, he became convinced that officers of the House were discriminating against him. He jumped to his feet, brandished a revolver and began chasing the officers out of the building. No one was hurt and Corbett was arrested. The following day, a judge declared Corbett insane and sent him to the Topeka Asylum for the Insane. On May 26, 1888, he escaped from the asylum on horseback.[29] He then rode to Neodesha, Kansas where he briefly stayed with Richard Thatcher, a man he had met while they were prisoners of war. When Corbett left, he told Thatcher he was going to Mexico.[28]

Rather than going to Mexico, Corbett is believed to have settled in a cabin he built in the forests near Hinckley, in Pine County in eastern Minnesota. He is believed to have died in the Great Hinckley Fire on September 1, 1894. Although there is no proof, the name "Thomas Corbett" appears on the list of dead and missing.[30][31]

In the years following Corbett's presumed death, several men came forwarding claiming to be "Lincoln's Avenger". A few years after Corbett was last seen in Neodesha, Kansas, a patent medicine salesman in Enid, Oklahoma filed an application using Corbett's name to receive pension benefits. After an investigation proved that the man was not Boston Corbett, he was sent to prison. In September 1905, a man arrested in Dallas also claimed to be Corbett. He too was proven to be an impostor and was sent to prison for perjury and then to the Government Hospital for the Insane.[32]

Memorials

In 1958, Boy Scout Troop 31 of Concordia, Kansas, built a roadside monument to Corbett located on Key Road. A small sign was also placed to mark the dug hole where Corbett had lived for a time.[33]

In popular culture

Character actor Dabbs Greer portrayed a fictional version of Corbett in "The Unmasked", a 1962 episode of the ABC western series Lawman.

Corbett appears as a prominent and possibly prophetic character in Edward M. Erdelac's 2015 alternate historical horror novel Andersonville.

Notes

- 1 2 3 Jameson 2013, pp. 128

- 1 2 3 Walker & Jakes 1998, p. 159

- 1 2 Johnson 1914, p. 45

- ↑ Walker & Jakes 1998, p. 160

- ↑ Harper's Weekly, May 13, 1865

- ↑ Kauffman 2004, p. 310

- ↑ Johnson 1914, p. 46

- ↑ Johnson 1914, pp. 45–46

- ↑ Swanson 2007, p. 329

- ↑ Walker & Jakes 1998, pp. 160–161

- 1 2 3 Walker & Jakes 1998, p. 161

- ↑ Jameson 2013, p. 129

- ↑ Chamlee & Chamlee 1989, p. 289

- ↑ Chipman 1891, p. 40

- ↑ Swanson 2007, pp. 324–335

- ↑ "The Death of John Wilkes Booth, 1865". Eyewitness to History/Ibis Communications. Retrieved August 16, 2012. (Quoting Lieutenant Edward Doherty, officer in charge of the soldiers who captured Booth)

- ↑ Jameson 2013, p. 135

- ↑ Swanson 2007, p. 340

- 1 2 Goodrich 2005, p. 227

- ↑ Goodrich 2005, pp. 227–228

- 1 2 Basler, Roy (1965). The Assassination and History of the Conspiracy. New York: Hobbs, Dorman & Company, INC. pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Nottingham 1997, p. 148

- ↑ Goodrich 2005, p. 228

- 1 2 Goodrich 2005, p. 291

- ↑ Swanson 2007, p. 358

- 1 2 Frazier, Robert B. (January 3, 1967). "The Strange Fate Of Boston Corbett". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 5. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- 1 2 Sparks et al. 1889, p. 382

- 1 2 Johnson 1914, p. 51

- ↑ Walker, Dale (September 2005). "The Mad Hatter". American Cowboy. Active Interest Media, Inc. 12 (3): 82. ISSN 1079-3690. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ↑ Lincoln Herald, Volume 86, Lincoln Memorial University Press., 1984, pp. 152–155

- ↑ Kubicek, Earl C, "The Case of the Mad Hatter", Lincoln Herald, Volume 83, Lincoln Memorial University Press, 1981, pp. 708–719

- ↑ Johnson 1914, pp. 52–53

- ↑ "He Killed Lincoln's Killer, Then Lived In a Hole". Retrieved October 10, 2008.

References

- Chamlee, Roy Z.; Chamlee, Roy Z., Jr. (1989). Lincoln's Assassins: A Complete Account of Their Capture, Trial, and Punishment. McFarland. ISBN 0-89950-420-5.

- Chipman, Norton Parker (1891). The Horrors of Andersonville Rebel Prison: Trial of Henry Wirz, the Andersonville Jailer; Jefferson Davis' Defense of Andersonville Prison Fully Refuted. Bancroft Co.

- Goodrich, Thomas (2005). The Darkest Dawn: Lincoln, Booth, and the Great American Tragedy. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-11132-3.

- Jameson, W. C. (2013). John Wilkes Booth: Beyond the Grave. Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 1-589-79832-5.

- Johnson, Byron Berkeley (1914). Abraham Lincoln and Boston Corbett: With Personal Recollections of Each; John Wilkes Booth and Jefferson Davis, a True Story of Their Capture. B. B. Johnson.

- Kauffman, Michael W. (2004). American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. Random House. ISBN 0-375-50785-X.

- Nottingham, Theodore J. (1997). The Curse of Cain: The Untold Story of John Wilkes Booth. Theosis Books. ISBN 1-580-06021-8.

- Sparks, Jared; Everett, Edward; Lowell, James Russell; Lodge, Henry Cabot (1889). The North American Review, Volume 149. Making of America Project. University of Northern Iowa.

- Walker, Dale L.; Jakes, John (1998). Legends and Lies: Great Mysteries of the American West. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-86848-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boston Corbett. |