Boston Tea Party

Coordinates: 42°21′13″N 71°03′09″W / 42.3536°N 71.0524°W

| Boston Tea Party | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolution | |||

Source: W.D. Cooper. "Boston Tea Party.", The History of North America. London: E. Newberry, 1789. Engraving. Plate opposite p. 58. Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (40) | |||

| Date | 16 December 1773 | ||

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts, British America | ||

| Causes | Tea Act | ||

| Goals | To protest British Parliament's tax on tea. "No taxation without representation." | ||

| Methods | Throw the tea into Boston Harbor | ||

| Result | Intolerable Acts | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

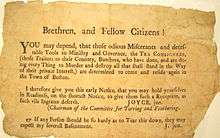

The Boston Tea Party (initially referred to by John Adams as "the Destruction of the Tea in Boston")[2] was a political protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, on December 16, 1773. The demonstrators, some disguised as Native Americans, in defiance of the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, destroyed an entire shipment of tea sent by the East India Company. They boarded the ships and threw the chests of tea into Boston Harbor. The British government responded harshly and the episode escalated into the American Revolution. The Tea Party became an iconic event of American history, and other political protests such as the Tea Party movement after 2010 explicitly refer to it.

The Tea Party was the culmination of a resistance movement throughout British America against the Tea Act, which had been passed by the British Parliament in 1773. Colonists objected to the Tea Act because they believed that it violated their rights as Englishmen to "No taxation without representation," that is, be taxed only by their own elected representatives and not by a British parliament in which they were not represented. Protesters had successfully prevented the unloading of taxed tea in three other colonies, but in Boston, embattled Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson refused to allow the tea to be returned to Britain.

The Boston Tea Party was a significant event in the growth of the American Revolution. Parliament responded in 1774 with the Coercive Acts, or Intolerable Acts, which, among other provisions, ended local self-government in Massachusetts and closed Boston's commerce. Colonists up and down the Thirteen Colonies in turn responded to the Coercive Acts with additional acts of protest, and by convening the First Continental Congress, which petitioned the British monarch for repeal of the acts and coordinated colonial resistance to them. The crisis escalated, and the American Revolutionary War began near Boston in 1775.

Background

The Boston Tea Party arose from two issues confronting the British Empire in 1765: the financial problems of the British East India Company; and an ongoing dispute about the extent of Parliament's authority, if any, over the British American colonies without seating any elected representation. The North Ministry's attempt to resolve these issues produced a showdown that would eventually result in revolution.[3]

Tea trade to 1767

As Europeans developed a taste for tea in the 17th century, rival companies were formed to import the product from China.[4] In England, Parliament gave the East India Company a monopoly on the importation of tea in 1698.[5] When tea became popular in the British colonies, Parliament sought to eliminate foreign competition by passing an act in 1721 that required colonists to import their tea only from Great Britain.[6] The East India Company did not export tea to the colonies; by law, the company was required to sell its tea wholesale at auctions in England. British firms bought this tea and exported it to the colonies, where they resold it to merchants in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston.[7]

Until 1767, the East India Company paid an ad valorem tax of about 25% on tea that it imported into Great Britain.[8] Parliament laid additional taxes on tea sold for consumption in Britain. These high taxes, combined with the fact that tea imported into the Dutch Republic was not taxed by the Dutch government, meant that Britons and British Americans could buy smuggled Dutch tea at much cheaper prices.[9] The biggest market for illicit tea was England—by the 1760s the East India Company was losing £400,000 per year to smugglers in Great Britain[10]—but Dutch tea was also smuggled into British America in significant quantities.[11]

In 1767, to help the East India Company compete with smuggled Dutch tea, Parliament passed the Indemnity Act, which lowered the tax on tea consumed in Great Britain, and gave the East India Company a refund of the 25% duty on tea that was re-exported to the colonies.[12] To help offset this loss of government revenue, Parliament also passed the Townshend Revenue Act of 1767, which levied new taxes, including one on tea, in the colonies.[13] Instead of solving the smuggling problem, however, the Townshend duties renewed a controversy about Parliament's right to tax the colonies.

Townshend duty crisis

Controversy between Great Britain and the colonies arose in the 1760s when Parliament sought, for the first time, to impose a direct tax on the colonies for the purpose of raising revenue. Some colonists, known in the colonies as Whigs, objected to the new tax program, arguing that it was a violation of the British Constitution. Britons and British Americans agreed that, according to the constitution, British subjects could not be taxed without the consent of their elected representatives. In Great Britain, this meant that taxes could only be levied by Parliament. Colonists, however, did not elect members of Parliament, and so American Whigs argued that the colonies could not be taxed by that body. According to Whigs, colonists could only be taxed by their own colonial assemblies. Colonial protests resulted in the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766, but in the 1766 Declaratory Act, Parliament continued to insist that it had the right to legislate for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever".

When new taxes were levied in the Townshend Revenue Act of 1767, Whig colonists again responded with protests and boycotts. Merchants organized a non-importation agreement, and many colonists pledged to abstain from drinking British tea, with activists in New England promoting alternatives, such as domestic Labrador tea.[14] Smuggling continued apace, especially in New York and Philadelphia, where tea smuggling had always been more extensive than in Boston. Dutied British tea continued to be imported into Boston, however, especially by Richard Clarke and the sons of Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson, until pressure from Massachusetts Whigs compelled them to abide by the non-importation agreement.[15]

Parliament finally responded to the protests by repealing the Townshend taxes in 1770, except for the tea duty, which Prime Minister Lord North kept to assert "the right of taxing the Americans".[16] This partial repeal of the taxes was enough to bring an end to the non-importation movement by October 1770.[17] From 1771 to 1773, British tea was once again imported into the colonies in significant amounts, with merchants paying the Townshend duty of three pence per pound.[18] Boston was the largest colonial importer of legal tea; smugglers still dominated the market in New York and Philadelphia.[19]

Tea Act of 1773

The Indemnity Act of 1767, which gave the East India Company a refund of the duty on tea that was re-exported to the colonies, expired in 1772. Parliament passed a new act in 1772 that reduced this refund, effectively leaving a 10% duty on tea imported into Britain.[20] The act also restored the tea taxes within Britain that had been repealed in 1767, and left in place the three pence Townshend duty in the colonies. With this new tax burden driving up the price of British tea, sales plummeted. The company continued to import tea into Great Britain, however, amassing a huge surplus of product that no one would buy.[21] For these and other reasons, by late 1772 the East India Company, one of Britain's most important commercial institutions, was in a serious financial crisis.[22]

Eliminating some of the taxes was one obvious solution to the crisis. The East India Company initially sought to have the Townshend duty repealed, but the North ministry was unwilling because such an action might be interpreted as a retreat from Parliament's position that it had the right to tax the colonies.[23] More importantly, the tax collected from the Townshend duty was used to pay the salaries of some colonial governors and judges.[24] This was in fact the purpose of the Townshend tax: previously these officials had been paid by the colonial assemblies, but Parliament now paid their salaries to keep them dependent on the British government rather than allowing them to be accountable to the colonists.[25]

Another possible solution for reducing the growing mound of tea in the East India Company warehouses was to sell it cheaply in Europe. This possibility was investigated, but it was determined that the tea would simply be smuggled back into Great Britain, where it would undersell the taxed product.[26] The best market for the East India Company's surplus tea, so it seemed, was the American colonies, if a way could be found to make it cheaper than the smuggled Dutch tea.[27]

The North ministry's solution was the Tea Act, which received the assent of King George on May 10, 1773.[28] This act restored the East India Company's full refund on the duty for importing tea into Britain, and also permitted the company, for the first time, to export tea to the colonies on its own account. This would allow the company to reduce costs by eliminating the middlemen who bought the tea at wholesale auctions in London.[29] Instead of selling to middlemen, the company now appointed colonial merchants to receive the tea on consignment; the consignees would in turn sell the tea for a commission. In July 1773, tea consignees were selected in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Charleston.[30]

The Tea Act retained the three pence Townshend duty on tea imported to the colonies. Some members of Parliament wanted to eliminate this tax, arguing that there was no reason to provoke another colonial controversy. Former Chancellor of the Exchequer William Dowdeswell, for example, warned Lord North that the Americans would not accept the tea if the Townshend duty remained.[31] But North did not want to give up the revenue from the Townshend tax, primarily because it was used to pay the salaries of colonial officials; maintaining the right of taxing the Americans was a secondary concern.[32] According to historian Benjamin Labaree, "A stubborn Lord North had unwittingly hammered a nail in the coffin of the old British Empire."[33]

Even with the Townshend duty in effect, the Tea Act would allow the East India Company to sell tea more cheaply than before, undercutting the prices offered by smugglers, but also undercutting colonial tea importers, who paid the tax and received no refund. In 1772, legally imported Bohea, the most common variety of tea, sold for about 3 shillings (3s) per pound.[34] After the Tea Act, colonial consignees would be able to sell it for 2 shillings per pound (2s), just under the smugglers' price of 2 shillings and 1 penny (2s 1d).[35] Realizing that the payment of the Townshend duty was politically sensitive, the company hoped to conceal the tax by making arrangements to have it paid either in London once the tea was landed in the colonies, or have the consignees quietly pay the duties after the tea was sold. This effort to hide the tax from the colonists was unsuccessful.[36]

Resisting the Tea Act

.jpg)

In September and October 1773, seven ships carrying East India Company tea were sent to the colonies: four were bound for Boston, and one each for New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston.[37] In the ships were more than 2,000 chests containing nearly 600,000 pounds of tea.[38] Americans learned the details of the Tea Act while the ships were en route, and opposition began to mount.[39] Whigs, sometimes calling themselves Sons of Liberty, began a campaign to raise awareness and to convince or compel the consignees to resign, in the same way that stamp distributors had been forced to resign in the 1765 Stamp Act crisis.[40]

The protest movement that culminated with the Boston Tea Party was not a dispute about high taxes. The price of legally imported tea was actually reduced by the Tea Act of 1773. Protesters were instead concerned with a variety of other issues. The familiar "no taxation without representation" argument, along with the question of the extent of Parliament's authority in the colonies, remained prominent.[41] Samuel Adams considered the British tea monopoly to be "equal to a tax" and to raise the same representation issue whether or not a tax was applied to it.[42] Some regarded the purpose of the tax program—to make leading officials independent of colonial influence—as a dangerous infringement of colonial rights.[43] This was especially true in Massachusetts, the only colony where the Townshend program had been fully implemented.[44]

Colonial merchants, some of them smugglers, played a significant role in the protests. Because the Tea Act made legally imported tea cheaper, it threatened to put smugglers of Dutch tea out of business.[45] Legitimate tea importers who had not been named as consignees by the East India Company were also threatened with financial ruin by the Tea Act.[46] Another major concern for merchants was that the Tea Act gave the East India Company a monopoly on the tea trade, and it was feared that this government-created monopoly might be extended in the future to include other goods.[47]

South of Boston, protesters successfully compelled the tea consignees to resign. In Charleston, the consignees had been forced to resign by early December, and the unclaimed tea was seized by customs officials.[48] There were mass protest meetings in Philadelphia. Benjamin Rush urged his fellow countrymen to oppose the landing of the tea, because the cargo contained "the seeds of slavery".[49] By early December, the Philadelphia consignees had resigned and the tea ship returned to England with its cargo following a confrontation with the ship's captain.[50] The tea ship bound for New York City was delayed by bad weather; by the time it arrived, the consignees had resigned, and the ship returned to England with the tea.[51]

Standoff in Boston

In every colony except Massachusetts, protesters were able to force the tea consignees to resign or to return the tea to England.[52] In Boston, however, Governor Hutchinson was determined to hold his ground. He convinced the tea consignees, two of whom were his sons, not to back down.[53]

When the tea ship Dartmouth arrived in the Boston Harbor in late November, Whig leader Samuel Adams called for a mass meeting to be held at Faneuil Hall on November 29, 1773. Thousands of people arrived, so many that the meeting was moved to the larger Old South Meeting House.[54] British law required the Dartmouth to unload and pay the duties within twenty days or customs officials could confiscate the cargo.[55] The mass meeting passed a resolution, introduced by Adams and based on a similar set of resolutions promulgated earlier in Philadelphia, urging the captain of the Dartmouth to send the ship back without paying the import duty. Meanwhile, the meeting assigned twenty-five men to watch the ship and prevent the tea—including a number of chests from Davison, Newman and Co. of London—from being unloaded.[56]

Governor Hutchinson refused to grant permission for the Dartmouth to leave without paying the duty. Two more tea ships, the Eleanor and the Beaver, arrived in Boston Harbor (there was another tea ship headed for Boston, the William, but it encountered a storm and was destroyed before it could reach its destination[57]). On December 16—the last day of the Dartmouth's deadline—about 7,000 people had gathered around the Old South Meeting House.[58] After receiving a report that Governor Hutchinson had again refused to let the ships leave, Adams announced that "This meeting can do nothing further to save the country." According to a popular story, Adams's statement was a prearranged signal for the "tea party" to begin. However, this claim did not appear in print until nearly a century after the event, in a biography of Adams written by his great-grandson, who apparently misinterpreted the evidence.[59] According to eyewitness accounts, people did not leave the meeting until ten or fifteen minutes after Adams's alleged "signal", and Adams in fact tried to stop people from leaving because the meeting was not yet over.[60]

Destruction of the tea

While Samuel Adams tried to reassert control of the meeting, people poured out of the Old South Meeting House to prepare to take action. In some cases, this involved donning what may have been elaborately prepared Mohawk costumes.[61] While disguising their individual faces was imperative, because of the illegality of their protest, dressing as Mohawk warriors was a specific and symbolic choice. It showed that the Sons of Liberty identified with America, over their official status as subjects of Great Britain.[62]

That evening, a group of 30 to 130 men, some dressed in the Mohawk warrior disguises, boarded the three vessels and, over the course of three hours, dumped all 342 chests of tea into the water.[63] The precise location of the Griffin's Wharf site of the Tea Party has been subject to prolonged uncertainty; a comprehensive study[64] places it near the foot of Hutchinson Street (today's Pearl Street).

Reaction

Whether or not Samuel Adams helped plan the Boston Tea Party is disputed, but he immediately worked to publicize and defend it.[65] He argued that the Tea Party was not the act of a lawless mob, but was instead a principled protest and the only remaining option the people had to defend their constitutional rights.[66]

By "constitution" he referred to the idea that all governments have a constitution, written or not, and that the constitution of Great Britain could be interpreted as banning the levying of taxes without representation. For example, the Bill of Rights of 1689 established that long-term taxes could not be levied without Parliament, and other precedents said that Parliament must actually represent the people it ruled over, in order to "count".

Governor Thomas Hutchinson had been urging London to take a hard line with the Sons of Liberty. If he had done what the other royal governors had done and let the ship owners and captains resolve the issue with the colonists, the Dartmouth, Eleanor and the Beaver would have left without unloading any tea.

In Britain, even those politicians considered friends of the colonies were appalled and this act united all parties there against the colonies. The Prime Minister Lord North said, "Whatever may be the consequence, we must risk something; if we do not, all is over".[67] The British government felt this action could not remain unpunished, and responded by closing the port of Boston and putting in place other laws known as the "Coercive Acts." Benjamin Franklin stated that the destroyed tea must be paid for, all ninety thousand pounds (which, at two shillings per pound, came to £9,000, or £1.03 million [2014, approx. $1.7 million US]).[68] Robert Murray, a New York merchant, went to Lord North with three other merchants and offered to pay for the losses, but the offer was turned down.[69]

The incident resulted in a similar effect in America when news of the Boston Tea Party reached London in January and Parliament responded with a series of acts known collectively in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts. These were intended to punish Boston for the destruction of private property, restore British authority in Massachusetts, and otherwise reform colonial government in America. Although the first two, the Boston Port Act and the Massachusetts Government Act, applied only to Massachusetts, colonists outside that colony feared that their governments could now also be changed by legislative fiat in England. The Intolerable Acts were viewed as a violation of constitutional rights, natural rights, and colonial charters, and united many colonists throughout America,[70] exemplified by the calling of the First Continental Congress in September 1774.

A number of colonists were inspired by the Boston Tea Party to carry out similar acts, such as the burning of the Peggy Stewart. The Boston Tea Party eventually proved to be one of the many reactions that led to the American Revolutionary War. In his December 17, 1773 entry in his diary, John Adams wrote:

Last Night 3 Cargoes of Bohea Tea were emptied into the Sea. This Morning a Man of War sails.This is the most magnificent Movement of all. There is a Dignity, a Majesty, a Sublimity, in this last Effort of the Patriots, that I greatly admire. The People should never rise, without doing something to be remembered—something notable And striking. This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences, and so lasting, that I cant but consider it as an Epocha in History.[71]

There was a repeat performance on March 7, 1774, but it was much less destructive.[72]

In February 1775, Britain passed the Conciliatory Resolution, which ended taxation for any colony that satisfactorily provided for the imperial defense and the upkeep of imperial officers. The tax on tea was repealed with the Taxation of Colonies Act 1778, part of another Parliamentary attempt at conciliation that failed.

Legacy

John Adams and many other Americans considered tea drinking to be unpatriotic following the Boston Tea Party. Tea drinking declined during and after the Revolution, resulting in a shift to coffee as the preferred hot drink.[73]

According to historian Alfred Young, the term "Boston Tea Party" did not appear in print until 1834.[74] Before that time, the event was usually referred to as the "destruction of the tea". According to Young, American writers were for many years apparently reluctant to celebrate the destruction of property, and so the event was usually ignored in histories of the American Revolution. This began to change in the 1830s, however, especially with the publication of biographies of George Robert Twelves Hewes, one of the few still-living participants of the "tea party", as it then became known.[75]

The issue was never the tax but how the tax was passed without American input; United States Congress taxed tea from 1789 to 1872.[76]

The Boston Tea Party has often been referenced in other political protests. When Mohandas K. Gandhi led a mass burning of Indian registration cards in South Africa in 1908, a British newspaper compared the event to the Boston Tea Party.[77] When Gandhi met with the British viceroy in 1930 after the Indian salt protest campaign, Gandhi took some duty-free salt from his shawl and said, with a smile, that the salt was "to remind us of the famous Boston Tea Party."[78]

American activists from a variety of political viewpoints have invoked the Tea Party as a symbol of protest. In 1973, on the 200th anniversary of the Tea Party, a mass meeting at Faneuil Hall called for the impeachment of President Richard Nixon and protested oil companies in the ongoing oil crisis. Afterwards, protesters boarded a replica ship in Boston Harbor, hanged Nixon in effigy, and dumped several empty oil drums into the harbor.[79] In 1998, two conservative US Congressmen put the federal tax code into a chest marked "tea" and dumped it into the harbor.[80]

In 2006, a libertarian political party called the "Boston Tea Party" was founded. In 2007, the Ron Paul "Tea Party" money bomb, held on the 234th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, broke the one-day fund-raising record by raising $6.04 million in 24 hours.[81] Subsequently, these fund-raising "Tea parties" grew into the Tea Party movement, which dominated politics for the next two years, culminating in a voter victory for the Republicans in 2010 who were widely elected to seats in the United States House of Representatives.

Boston Tea Party Ships and Museum

The Boston Tea Party Museum is located on the Congress Street Bridge in Boston. It features reenactments, a documentary, and a number of interactive exhibits. The museum features two replica ships of the period, the Eleanor and the Beaver. Additionally, the museum possesses one of two known tea chests from the original event, part of its permanent collection.[82]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Young, Shoemaker, 183–85.

- ↑ John Adams: Revolutionary Writings 1755–1775 (PDF).

This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences, and so lasting, that I cant but consider it as an Epocha in History.

- ↑ Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (2010) ch. 1

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 3–4.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Growth, 90.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Growth, 90; Labaree, Tea Party, 7.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 8–9.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 6–8; Knollenberg, Growth, 91; Thomas, Townshend Duties, 18.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 6.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 59.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 6–7.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 13; Thomas, Townshend Duties, 26–27. This kind of refund or rebate is known as a "drawback".

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 21.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 27–30.

- ↑ Labaree, "Tea Party", 32–34.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Growth, 71; Labaree, Tea Party, 46.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 46–49.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 50–51.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 52.

- ↑ The 1772 tax act was 12 Geo. III c. 60 sec. 1; Knollenberg, Growth, 351n12.

- ↑ Thomas, Townshend Duties, 248–49; Labaree, Tea Party, 334.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 58, 60–62.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Growth, 90–91.

- ↑ Thomas, Townshend Duties, 252–54.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Growth, 91.

- ↑ Thomas, Townshend Duties, 250; Labaree, Tea Party, 69.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 70, 75.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Growth, 93.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 67, 70.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 75–76.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 71; Thomas, Townshend Duties, 252.

- ↑ Thomas, Townshend Duties, 252.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 72–73.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 51.

- ↑ Thomas, Townshend Duties, 255; Labaree, Tea Party, 76–77.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 76–77.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 78–79.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 77, 335.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 89–90.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Growth, 96.

- ↑ Thomas, Townshend Duties, 246.

- ↑ Gross, David M. (2014). 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns. Picket Line Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1490572741.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 106.

- ↑ Thomas, Townshend Duties, 245.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 102; see also John W. Tyler, Smugglers & Patriots: Boston Merchants and the Advent of the American Revolution (Boston, 1986).

- ↑ Thomas, Townshend Duties, 256.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Growth, 95–96.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Growth, 101.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 100. See also Alyn Brodsky, Benjamin Rush (Macmillan, 2004), 109.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 97.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 96; Knollenberg, Growth, 101–02.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 96–100.

- ↑ Labaree, Tea Party, 104–05.

- ↑ This was not an official town meeting, but a gathering of "the body of the people" of greater Boston; Alexander, Revolutionary Politician, 123.

- ↑ Alexander, Revolutionary Politician, 124.

- ↑ Alexander, Revolutionary Politician, 123.

- ↑ The Story of the Boston Tea Party Ships by The Boston Tea Party Historical Society

- ↑ Alexander, Revolutionary Politician, 125.

- ↑ Raphael, Founding Myths, 53.

- ↑ Maier, Old Revolutionaries, 27–28n32; Raphael, Founding Myths, 53. For firsthand accounts that contradict the story that Adams gave the signal for the tea party, see L. F. S. Upton, ed., "Proceeding of Ye Body Respecting the Tea," William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 22 (1965), 297–98; Francis S. Drake, Tea Leaves: Being a Collection of Letters and Documents, (Boston, 1884), LXX; Boston Evening-Post, December 20, 1773; Boston Gazette, December 20, 1773; Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter, December 23, 1773.

- ↑ "Boston Tea Party Historical Society".

- ↑ "Boston Tea Party Historical Society".

- ↑ Alexander, Revolutionary Politician, 125–26; Labaree, Tea Party, 141–44.

- ↑ "Where Was the Actual Boston Tea Party Site?".

- ↑ Alexander, Revolutionary Politician, 126.

- ↑ Alexander, Revolutionary Politician, 129.

- ↑ Cobbett, Parliamentary History of England, XVII, pg. 1280-1281

- ↑ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ Ketchum, Divided Loyalties, 262.

- ↑ Ammerman, In the Common Cause, 15.

- ↑ Diary of John Adams, Volume 2 http://www.masshist.org/publications/apde/portia.php?id=DJA02d100

- ↑ Diary of John Adams, March 8, 1774; Boston Gazette, March 14, 1774

- ↑ (1) Adams, John (July 6, 1774). "John Adams to Abigail Adams". The Adams Papers: Digital Editions: Adams Family Correspondence, Volume 1. Massachusetts Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-25.

I believe I forgot to tell you one Anecdote: When I first came to this House it was late in the Afternoon, and I had ridden 35 miles at least. “Madam” said I to Mrs. Huston, “is it lawfull for a weary Traveller to refresh himself with a Dish of Tea provided it has been honestly smuggled, or paid no Duties?” “No sir, said she, we have renounced all Tea in this Place. I cant make Tea, but I'le make you Coffee.” Accordingly I have drank Coffee every Afternoon since, and have borne it very well. Tea must be universally renounced. I must be weaned, and the sooner, the better.

(2) Stone, William L. (1867). "Continuation of Mrs. General Riedesel's Adventures". Mrs. General Riedesel: Letters and Journals relating to the War of Independence and the Capture of the Troops at Saratoga (Translated from the Original German). Albany: Joel Munsell. p. 147.She then became more gentle, and offered me bread and milk. I made tea for ourselves. The woman eyed us longingly, for the Americans love it very much; but they had resolved to drink it no longer, as the famous duty on the tea had occasioned the war.

At Google Books. Note: Fredricka Charlotte Riedesel was the wife of General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel, commander of all German and Indian troops in General John Burgoyne's Saratoga campaign and American prisoner of war during the American Revolution.

(3) Heiss, Mary Lou; Heiss, Robert .J (2007). "A History of Tea: The Boston Tea Party". The Story of Tea: A Cultural History and Drinking Guide. pp. 21–24. ISBN 9781607741725. At Google Books.

(4) Zuraw, Lydia (April 24, 2013). "How Coffee Influenced The Course Of History". NPR. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-25.

(5) DeRupo, Joseph (July 3, 2013). "American Revolution: Stars, Stripes—and Beans". NCA News. National Coffee Association. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-25.

(6) Luttinger, Nina; Dicum, Gregory (2006). The coffee book: anatomy of an industry from crop to the last drop. The New Press. p. 33. ISBN 9781595587244. At Google Books. - ↑ Young, Shoemaker, xv.

- ↑ Young, Shoemaker.

- ↑ Davis Dewey, Financial History of the United States, 1791-1901 (New York: Longmans, Green, 1902), 80-82.

- ↑ Erik H. Erikson, Gandhi's Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence (New York: Norton, 1969), 204.

- ↑ Erikson, Gandhi's Truth, 448.

- ↑ Young, Shoemaker, 197.

- ↑ Young, Shoemaker, 198.

- ↑ "Ron Paul's "tea party" breaks fund-raising record".

- ↑ "Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum". Retrieved 20 June 2013.

References

- Alexander, John K. Samuel Adams: America's Revolutionary Politician. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002. ISBN 0-7425-2115-X.

- Ammerman, David (1974). In the Common Cause: American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774. New York: Norton.

- Carp, Benjamin L. Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (Yale U.P., 2010) ISBN 978-0-300-11705-9

- Ketchum, Richard. Divided Loyalties: How the American Revolution came to New York. 2002. ISBN 0-8050-6120-7.

- Knollenberg, Bernhard. Growth of the American Revolution, 1766–1775. New York: Free Press, 1975. ISBN 0-02-917110-5.

- Labaree, Benjamin Woods. The Boston Tea Party. Originally published 1964. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-930350-05-7.

- Maier, Pauline. The Old Revolutionaries: Political Lives in the Age of Samuel Adams. New York: Knopf, 1980. ISBN 0-394-51096-8.

- Raphael, Ray. Founding Myths: Stories That Hide Our Patriotic Past. New York: The New Press, 2004. ISBN 1-56584-921-3.

- Thomas, Peter D. G. The Townshend Duties Crisis: The Second Phase of the American Revolution, 1767–1773. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-19-822967-4.

- Thomas, Peter D. G. Tea Party to Independence: The Third Phase of the American Revolution, 1773–1776. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991. ISBN 0-19-820142-7.

- Young, Alfred F. The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution. Boston: Beacon Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8070-5405-4; ISBN 978-0-8070-5405-5.

Further reading

- Unger, Harlow G. (2011). American Tempest: How the Boston Tea Party Sparked a Revolution. Boston, MA: Da Capo. ISBN 0306819627. OCLC 657595563.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boston Tea Party. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Boston Tea Party. |

- The Boston Tea Party Historical Society

- Eyewitness Account of the Event

- Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum

- Tea Party Finds Inspiration In Boston History – audio report by NPR

- Booknotes interview with Alfred Young on The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution, November 21, 1999

- BBC Radio program about the 'forgotten truth' behind the Boston Tea Party

- Eyewitness to History: The Boston Tea Party, 1773