Cervical fracture

| Cervical fracture | |

|---|---|

|

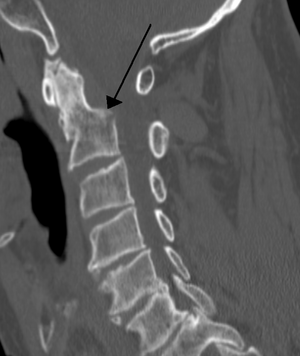

A fracture of the base of the dens (a part of C2) as seen on CT. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | emergency medicine |

| ICD-10 | S12 |

| ICD-9-CM | 805.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 2322 |

| MedlinePlus | 000029 |

| eMedicine | emerg/189 |

A cervical fracture, commonly called a broken neck, is a catastrophic fracture of any of the seven cervical vertebrae in the neck. Examples of common causes in humans are traffic collisions and diving into shallow water. Abnormal movement of neck bones or pieces of bone can cause a spinal cord injury resulting in loss of sensation, paralysis, or death.

Causes

Considerable force is needed to cause a cervical fracture. Vehicle collisions and falls are common causes. A severe, sudden twist to the neck or a severe blow to the head or neck area can cause a cervical fracture.

Sports that involve violent physical contact carry a risk of cervical fracture, including American football, Goalkeeper (association football), ice hockey, rugby, and wrestling. Spearing an opponent in football or rugby, for instance, can cause a broken neck. Cervical fractures may also be seen in some non-contact sports, such as gymnastics, skiing, diving, surfing, powerlifting, equestrianism, mountain biking, and motor racing (as in Formula One driver Gilles Villeneuve's death from a cervical fracture).

Certain penetrating neck injuries can also cause cervical fracture which can also cause internal bleeding among other complications.

Hanging also incurs a cervical fracture.

Diagnosis

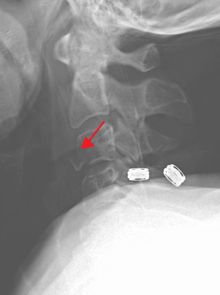

Severe pain will usually be present at the point of injury. Pressure on a nerve may also cause pain from the neck down the shoulders and/or arms. Bruising and swelling may be present at the back of the neck. A neurological exam will be performed to assess for spinal cord injury. X-rays will be ordered to determine the severity and location of the fracture. CT (computed tomography) scans may be ordered to assess for gross abnormalities not visible by regular X-ray. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) tests may be ordered to provide high resolution images of soft tissue and determine whether there has been damage to the spinal cord, although such damage is usually obvious in the conscious patient because of the immediate functional consequences of numbness and paralysis in much of the body.

It is also common for imaging (either a plain film X-ray or CT scan) to be completed when assessing a cervical injury. This is the most common way to diagnose the location and severity of the fracture. To decrease the use C-spine scans yielding negative findings for fracture, thus unnecessarily exposing people to radiation and increase time in the hospital and cost of the visit, multiple clinical decision support rules have been developed to help clinicians weigh the option to scan a patient with a neck injury. Among these are the Canadian C-spine rule[1] and the NEXUS criteria for C-Spine imaging,[2] which both help make these decisions from easily obtained information. Both rules are widely used in emergency departments and by paramedics.

Treatment

Complete immobilization of the head and neck should be done as early as possible and before moving the patient. Immobilization should remain in place until movement of the head and neck is proven safe. In the presence of severe head trauma, cervical fracture must be presumed until ruled out. Immobilization is imperative to minimize or prevent further spinal cord injury. The only exceptions are when there is imminent danger from an external cause, such as becoming trapped in a burning building.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), such as aspirin or ibuprofen, are contraindicated because they interfere with bone healing. Tylenol (acetaminophen) is a better option. Patients with cervical fractures will likely be prescribed medication for pain control.

In the long term, physical therapy will be given to build strength in the muscles of the neck to increase stability and better protect the cervical spine.

Collars, traction and surgery can be used to immobilize and stabilize the neck after a cervical fracture.

Cervical collar

Minor fractures can be immobilized with a cervical collar without need for traction or surgery. A soft collar is fairly flexible and is the least limiting but can carry a high risk of further neck damage in patients with osteoporosis. It can be used for minor injuries or after healing has allowed the neck to become more stable.

A range of manufactured rigid collars are also used, usually comprising a firm plastic bi-valved shell secured with Velcro straps and removable padded liners. The most frequently prescribed are the Aspen, Malibu, Miami J, and Philadelphia collars. All these can be used with additional chest and head extension pieces to increase stability.

Rigid braces

Rigid braces that support the head and chest are also prescribed.[3] Examples include the Sterno-Occipital Mandibular Immobilization Device (SOMI), Lerman Minerva and Yale types. Special patients, such as very young children or non-cooperative adults, are sometimes still immobilized in medical plaster of paris casts, such as the Minerva cast.

Traction

Traction can be applied by free weights on a pulley or a Halo type brace. The Halo brace is the most rigid cervical brace, used when limiting motion to the minimum that is essential, especially with unstable cervical fractures. It can provide stability and support during the time (typically 8–12 weeks) needed for the cervical bones to heal.

Surgery

Surgery may be needed to stabilize the neck and relieve pressure on the spinal cord. A variety of surgeries are available depending on the injury. Surgery to remove a damaged intervertebral disc may be done to relieve pressure on the spinal cord. The discs are cushions between the vertebrae. After the disc is removed, the vertebrae may be fused together to provide stability. Metal plates, screws, or wires may be needed to hold vertebrae or pieces in place.

See also

References

- ↑ Stiell IG, Wells GA, et al. (2001). "The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients.". JAMA. 186 (15): 1841–8. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1841. PMID 11597285.

- ↑ Hoffman JR, Wolfson AB, Todd K, Mower WR (1998). "Selective cervical spine radiography in blunt trauma: methodology of the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS).". Ann Emerg Med. 32 (4): 461–9. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70176-3. PMID 9774931.

- ↑ Shantanu S Kulkarni, DO and Robert H Meier III, "Spinal Orthotics", Medscape Reference.

External links

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Cervical Fracture. 9/12/2006.

- Brigham And Women's Hospital Health Information - Neck Fracture. 9/12/2006.

- Cervical Fracture - DynoMed.com

- CERVICAL FRACTURE Thomson MICROMEDEX. 9/12/2006.

- Van Waes OJ; et al. (Jan 2012). "Management of penetrating neck injuries". J.Br J Surg. 99 (Suppl 1): 149–54. doi:10.1002/bjs.7733. PMID 22441870.

- Nettina, Sandra M. The Lipnincoutt Manual of Nursing Practice. Lipincott, Williams, and Wilkins. Philadelphia. 2001.

- Sama, Andrew A., MD.eMedicine - Cervical Spine Injuries in Sports. 9/12/2006

- Pamphlet containing useful information for patients wearing a Halo Brace. 15/8/2007

- University of Michigan Pamphlet containing useful information for patients wearing a Halo Brace. 15/8/2007