Cecil E. Harris

| Cecil E. Harris | |

|---|---|

Harris in the cockpit of a Hellcat | |

| Nickname(s) |

"Cece" "Speedball" |

| Born |

December 2, 1916 Faulkton, South Dakota, United States |

| Died |

December 2, 1981 (aged 65) Groveton, Virginia, United States |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1941–67 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit |

USS Suwannee USS Intrepid |

| Battles/wars | Korean War |

| Awards |

Navy Cross Silver Star (2) Distinguished Flying Cross (3) Air Medal (3) |

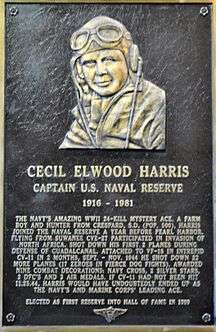

Captain Cecil E. "Cece" Harris (December 2, 1916 – December 2, 1981) was a school teacher, United States naval aviator and World War II ace fighter pilot. Harris is remembered for actions in the Pacific Ocean Theater which earned him nine combat medals including the Navy Cross, the highest award for valor after the Medal of Honor. With 24 confirmed kills, he ended the war as the Navy's second-highest-scoring ace.[1][2] Harris's performance is also remarkable for its consistency. He racked up 16 of his 24 aerial victories in just four days, downing 4 enemy aircraft each of those days. Not once during his 88-day tour with VF-18 did a single bullet so much as graze his aircraft.[3] Both feats were rarely if ever repeated by other American aces with similar scores. These facts, combined with Harris's truncated tour aboard the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid, led Barrett Tillman to say that he "was arguably the most consistently exceptional fighter pilot in the US Navy... only the battle damage sustained by Intrepid prevented him from challenging McCampbell's spot as 'topgun'."[4]

Pre-war

Cecil E. Harris was born in Faulkton, South Dakota on December 2, 1916. After graduating from Cresbard High School in 1934, Harris attended Northern State Teachers' College (NTSC) for a year. He took a leave from school to teach for a few years in Onaka, South Dakota before returning to NTSC in 1940 to complete his degree. Upon returning to school he enrolled in a civilian pilot training course, which ultimately led to his enlistment in the United States Naval Reserve on March 26, 1941.[5][6] By March 12, 1942 Harris had earned his wings.[7]

World War II

Snapshot

Harris first served aboard the escort carrier USS Suwannee, reporting for duty on 30 May 1942.[8] He was a pilot in VGF-27, which provided support for Operation Torch in North Africa and later flew sorties in the Solomon Islands Campaign. During this latter period Harris, flying a Grumman F4F Wildcat as part of a detachment posted on Guadalcanal, scored his first aerial victory.[9] After his stint with Suwannee ended he was transferred to VF-36,[10] which was eventually re-designated as VF-18.[11] "Fighting 18" boarded USS Intrepid on 16 August 1944 as part of its Air Group 18.[12]

Though he was only a lieutenant at the time, many of VF-18's green pilots turned to Harris for advice.[13] Intrepid's skipper similarly recognized Harris's ability and made him flight operations officer. According to later testimony from his peers, the tactical and flight training Harris provided to his outfit helped see them through the war.[14][15] His prowess on the wing would save a number of them in more direct fashion, both in dog fights and carrier landings. On 29 October, Intrepid entered a squall with a Combat Air Patrol inbound. Though many from VB-18 and VT-18 were forced to water land, Harris used his dead reckoning and other navigation skills to find the carrier in the storm. He landed successfully and radioed information to men in the air, saving them from the risks of water landing and preserving valuable aircraft.[16]

After eleven weeks of flying combat missions from Intrepid with Air Group 18, Cecil Harris had scored 23 of the group's total 187 confirmed kills.[17] Over half of Harris's VF-18 kills derive from four separate engagements in which he downed at least four Japanese planes: 13 September over Negros island,[18] 12 October over Formosa,[19] 29 October over Clark Field on Luzon[20][21] and 25 November over Nielsen Field and en route to Intrepid.[17][22] This was a feat rarely replicated in U.S. Navy history. For each of these individual engagements Harris was awarded medals, culminating with the receipt of the Navy Cross for the actions of 29 October.[23] On 24 October, he shot down two Japanese floatplanes.[4] The kamikaze attacks of 25 November 1944 put Intrepid out of commission for a stretch and saw VF-18 detached from Air Group 18. VF-18 stayed for less than a week on USS Hancock before it detached yet again, this time for Pearl Harbor; Cecil Harris was headed home. He arrived stateside 16 January 1945.[24]

VF-18 was reformed and returned to Air Group 18 on 25 January 1945. A large number of former VF-18 fighter pilots returned to the reformed squadron, including Harris, who served as Flight Officer. He was married at Seaside, Oregon while serving with this outfit. Training commenced immediately at NAS Astoria in Oregon and continued at NAS North Island in San Diego, where the group was transferred on 19 April. The squadron trained in night fighting, the use of rockets, and on the newly introduced Grumman F8F Bearcat. They would never see combat as a unit due to the Japanese surrender in August of that year.[25]

Aerial victories

| Date | Type | Total | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 04/01/43 | 2 A6M Zeke | 2 | [26][9] |

| 09/13/44 | 1 A6M Zeke, 3 A6M Zeke 32 | 4 | [27] |

| 10/12/44 | 1 Ki-21 Sally, 1 Ki-48 Lily, 2 A6M Zeke | 4 | [28] |

| 10/14/44 | 3 D4Y Judy | 3 | [29] |

| 10/21/44 | 1 Ki-21 Sally (Assist) | N/A | [30] |

| 10/24/44 | 2 F1M Pete | 2 | [31] |

| 10/29/44 | 3 Ki-44 Tojo, 1 A6M Zeke | 4 | [32] |

| 11/19/44 | 1 A6M Zeke | 1 | [33] |

| 11/25/44 | 3 Ki-44 Tojo, 1 A6M3-32 Hamp | 4 | [20] |

| 24 | |||

VF-18 in detail

September

The air group cut its teeth off the coast of Babelthuap, the largest island of Palau, on 6 September 1944. Encountering no aerial opposition to speak of during any of the day's sorties, fighters escorted their bomber charges to the target areas, engaging in strafing of anti-aircraft positions and military installations along the western coast of the island. With meager anti-aircraft fire reported and partly cloudy skies, the air group dropped in excess of 46 tons of ordnance on its first day of bona fide combat. The next couple days in this target area brought more of the same.[34]

Things heated up significantly when the group moved on to Mindanao on 9 September. Anti-aircraft fire escalated exponentially, as did the significance of the air group's contribution to the war effort. CAG Ellis personally witnessed VT-18 score two direct hits on the runway at Matina with 1-ton bombs. Likewise, strikes later in the day cratered Daliao airfield rendering it inoperational.[35] This is also the first day Harris is mentioned in the VF-18 reports. During a dawn fighter sweep over the Davao Gulf, he led a division against shipping vessels which led to the sinking of two small craft and left a third, larger one ablaze.[36] After incendiary strikes on the 10th, the carrier spent a day refueling before moving on to the Visayas.[37]

Harris's ace status was cemented on 13 September when he and Lt. James Neighbours led divisions in a dawn strike against Negros. Both divisions flew 500 feet (150 m) above the dive and torpedo bombers they were shepherding to the day's targets, with Neighbors' division positioned forward and Harris's behind the more sluggish bomber craft. By the time Harris et al. crossed over the island's coastline, USS Bunker Hill's Air Group 8 was already tangling with Japanese air defense. Enemy aircraft moved quickly to intercept the new arrivals. Harris and his wingman Franklin "Jimmy" Burley, along with the other two men in the division, kicked off the action.[38]

The first target was a lone Zeke making a run on the bombers. The four pilots pounced right away, forcing the intruder to dive down into cloud cover. They raced in after it and broke through the clouds to find not one but over a dozen enemy planes circling above Fabrica air strip—a veritable "hornets nest" as the air group's official history puts it.[39] There was no hope of making an accurate run on such short notice and at such speeds. Plunging down to 500 feet (150 m), Harris and Burley used their built up speed to zoom back up to 2,500 feet (760 m), right into the mass of surprised Japanese pilots. One Zeke bolted from the group and took off running, Burley on its tail in hot pursuit. He hit his quarry but did not have time to verify the kill: another Zero was coming in from behind, forcing him to take evasive action. Fortunately for Burley, Harris was behind this second Japanese fighter and blasted him out of the sky just a moment later. Leaving the scrum to head back to formation, Harris spotted a single Zeke 32 climbing ahead of him heading in the same direction, apparently intent on jumping the bomber squadrons. Harris pulled in above the enemy and turned inside of him, putting a burst into the plane from 7 o'clock and sending it down in flames. There was no time for rest after the first two victories, however. Harris's division had its hands full over Fabrica. As he was moving to assist his division, Harris was jumped from above, on his 7 o'clock, by two Zeke 32s. He pulled up hard and swung left, allowing his pursuers to overshoot their runs before he tacked back to the right, putting himself above and behind them. Diving on the pair and easily outpacing them, Harris blasted one so badly that it exploded mid-air as the other fled the scene. Once more seeking out his division, Harris approached a cluster of planes that turned out to be yet more Zeke 32s. Harris's Hellcat had no problem outpacing these bandits. After he'd put enough distance between himself and his pursuers, the lone American fighter looped back and approached the enemy formation head on in a low side run. His target, the last Zeke in formation, exploded a mere 200 feet (61 m) from Harris, who finally spotted some fellow Hellcats and broke off his engagement to follow them to the rendezvous point.[40]

13 September represented the first day that Air Group 18 encountered significant resistance in the Pacific skies. From Harris's Strike 2 Able through to the fourth and final strike of the day, Strike 2 Dog, 41 Japanese planes were shot down by Admiral Bogan's Task Group 38.2 and a similar number were destroyed on the ground by bombing and strafing runs.[41]

On 14 September Harris was credited with damaging a Sally on the ground during strafing attacks on Alicante airstrip.[42] The next day the task group retired to rendezvous with oilers and escort carriers, which refueled the ships and provided replacement aircraft on the 16th. Heading off the coast of the Palaus, the air group provided all day air support for Marine landings during the Battle of Peleliu on 17 September. The fighter squadron loaded their belly tanks with napalm to drop on targets at Peleliu and Angaur in addition to the conventional bombs dropped by the VB and VT squadrons.[43] 18–20 September were spent refueling and moving towards the next target: Luzon.[44]

Air Group 18 and the other air groups in ComCarDiv 4 flew the first carrier strikes on Luzon since its capture by Japanese forces, making strikes on shipping in the proximity of Subic Bay and bombing installations at Clark Field between 21 and 22 September. The first of these was a banner day for VF-18's fighter pilots. Lt(jg) Charles M. Mallory made ace in a day with 5 aircraft to his name; Lt. Harvey P. Picken destroyed 4½.[45] One of the last actions taken before the task group retired to Ulithi for the remainder of September was a long-range fighter-bomber strike on shipping in Coron Bay. Achieving total surprise on the morning of 24 September, Air Group 18 alone reportedly accounted for around 50,000 tons sunk.[46]

October

Fully half of Harris's credited kills were achieved in October. On 1 October 1944, while still anchored at Ulithi, Intrepid was made Admiral Gerald F. Bogan's Flag Ship. The carrier disembarked from harbor on 7 October to head for the waters southeast of Okinawa. It was scheduled to be part of strikes on Okinawa, the Ryukyus and Luzon leading up to a planned invasion of Leyte.[47]

10 October kicked off the month's activity with attacks on Okinawan airfields including Naha, Yontan and Ie Shima, as well as the usual strikes on nearby shipping. Anti-aircraft fire ranged from meager to intense with flak worsening throughout the day, but regardless of strike time or target there was virtually no aerial opposition encountered.[48]

Airfields, harbors and shipping were also the targets on 12 October, this time in northern Formosa. And this time the air groups would weather both ground fire and dogfights. The first fighter sweep of the day launched into overcast skies at 06:17 and headed for Shinchiku Airfield with VF-18 flying low cover. Absent any opposition in the air, the strike leader called for bombing runs on the target. Unfortunately the Japanese were alerted to the formation's presence ahead of time, and the morning's protective cloud cover dissipated into clear skies above Shinchiku. Flak of all caliber was intense as a result. Cecil Harris and the other Intrepid fighters led the charge, pushing over in glide bombing attacks on hangars around the strip. It was hard to determine the efficacy of the attacks as a result of the intensity of anti-aircraft activity; opportunities for strafing planes on the ground were also compromised for this reason. After the bombs dropped, the lightened fighters swung north to head for their next target, Matsuyama Airfield. On the way to Matsuyama the cloud cover thickened once more. VF-18 divisions were still flying low cover at this point, cruising at approximately 9,000 feet (2,700 m) between a floor of cumulus at 3,000 feet (910 m) and a ceiling of stratus at 11,000 feet (3,400 m). Just shy of Taien Airfield these pilots spotted around 6 Japanese bombers working their way down towards the lower clouds, seemingly on a landing approach. The lumbering twin engine bombers were no match for nimble Hellcats, and in mere minutes the Americans—including Harris, who bagged two—had completely taken out the bomber group.[49]

No sooner had the fighters destroyed their quarry than over a dozen Zekes poured from the clouds above to harry them, filtering down in small groups until as many as 40 Japanese fighters were swarming around the startled pilots of TG 38.2. Starting with an altitude disadvantage and relying on their planes' superior climb rate, the Hellcat pilots fought from 10,000 feet (3,000 m) all the way down to the tree tops, most ditching section and division tactics in the confusion of the melee. Carrier pilots did their best to lead the Zekes chasing them in front of other task group pilots while simultaneously pursuing their own bounty. Harris claimed two more during this wild encounter, and his wingman "Jimmy" Burley got three. They managed to stick together during the entirety of the attack. Judging by the angle of fire reported in the Aircraft Action Reports for VF-18, Harris shot down both of his Zekes during dogged pursuit, coming in from behind in each case and blasting through the enemy's cockpit. By the end of the fight, VF-18 alone accounted for 25 Japanese planes shot out of the sky and itself suffered 3 losses.[50]

14 October brought a Japanese response to the punishment TG 38.2 had been dishing out on Formosa for the past few days. Jill and Judy bombers were sent out on a bombing/torpedo mission against the task group, groping their way through rain squalls and the overcast intent on returning the favor.[51] Already in the air for over two hours, VF-18's CAP was vectored to intercept the bandits just outside the task group's picket. VF-18's CAP beat back first the formation of twelve bombers that erupted from the clouds, and then another 6–9 stragglers arrived on their heels.[52]

Two recently launched divisions of VF-18 snooper anti-submarine patrol (SNASP) were also routed to intercept, including one division led by Cecil Harris. Harris's division had barely finished grouping up after launch when they sighted and pounced on the straggling Judys. Harris quickly put bursts into one causing it to explode midair, then raked a second and sent it smoking towards the water where his wingman Burley saw it crash. As with the CAP fighters, the biggest risk posed to the SNASP Hellcats was their own task group's anti-aircraft fire. Harris and company withdrew back to the edge of the screen to protect themselves from friendly fire only to find a third Judy being chased by another Hellcat. The pilot of this plane, Frank Hearell, Jr., could not hit his target as the guns on his new (and uninspected) plane were mis-sighted and burned out. Harris swept in to help out and shot down the Judy, which crashed into the sea.[53]

At the end of the day, only 1 out of an estimated 30 bombers penetrated the picket, putting a bomb just shy of the carrier Hancock. Harvey P. Picken of VF-18 also scored 3 this on this day to bring his total to 11. According to the Air Group's War History, the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet wrote of the recent activity of the Third Fleet:[54]

My congratulations to you on the recent Pacific news. Will you please join Bard, Gates and myself in your messages to Halsey and Mitscher. The air and sea power of the THIRD FLEET is making history. All hands in the long line of support throughout the Navy are grateful for the opportunity of working for such a team — James ForrestalIn its recent crucial offensive the THIRD FLEET has been a source of pride to us all and has inflicted destruction and disaster on our enemy which he will not forget. WELL DONE. Signed CinCPac.

The task group moved on from Formosa to Luzon in anticipation of "A" Day, sending out sorties against Aparri Harbor and Laog Airfield on 18 October en route to support the Sixth Army's amphibious invasion of Leyte. Once TG 38.2 was in position for air support of General Douglas MacArthur's troops, its air groups conducted strikes intended to disrupt the anticipated Japanese air response. During the very first strike of this operation, a fighter sweep between 06:12 and 10:47 on 21 October, "Chink" Burley notched his score up by one with an assist courtesy of Harris. The two tag-teamed a Sally found in the vicinity of San Jose air base on Panay Island. First Harris hit the cockpit from 6 o'clock and left it smoking. Burley came in under Harris also firing from just behind the Sally—his .50 caliber guns turned smoke into flame. Harris finally came in on a third pass that turned a fire into an explosion, once and for all finishing the lone bandit. Subsequent strikes 2Able and 2Baker were launched against Negros, Ilo Ilo and Panay. There was no anti-aircraft fire to speak of and hardly any air opposition, either.[55]

Decisions made during the next two days had a dramatic impact on the experience of Air Group 18 at the Battle of Leyte Gulf. TG 38.1 was detached and sent to Ulithi for replenishment and rearmament after two weeks of continuous operations against Okinawa and the Ryukyus. USS Bunker Hill and Hancock were also detached from TG 38.2 at this time, leaving Intrepid the sole large carrier in its group. When Admiral Kurita's Center Force was sighted entering the Sibuyan Sea on 24 October, the only task group readily available to strike was the shorthanded TG 38.2.[56]

Pilots of Air Group 18 reported that 24 October was their toughest day yet.[57] Those assigned to the day's three strikes took on Center Force and its Yamato-class battleships, fearsome vessels bristling with armaments including nine 18.1-inch (460 mm) guns. Over the course of those strikes three VT-18 TBMs and two VB Helldivers were shot down; in addition to those listed as missing from the downed planes, two others were seriously injured. Cecil Harris was on a special search mission of 4 VF along the northwest coast of Palawan Island in the early hours of the day. Though they did not turn up any targets of value in the area of Imuruan Bay, Harris did spot and subsequently destroy two Petes bringing his total score to 15.[58]

Though the Japanese battleship Musashi was sunk after taking a great deal of punishment from the Intrepid group, Center Force was able to limp away back through San Bernardino Strait with Japanese battleship Yamato and a number of other ships intact. Rather than staying to finish it off, Intrepid was called north to go after a reported Japanese carrier group, Northern Force, which it encountered on 25 October. Anti-aircraft fire was once again extremely intense but this time Air Group 18 made it through the day without the loss of a single pilot.[59] The group's strikes were reported to have probably sunk a light carrier and to have damaged both a carrier and a second light carrier.[60] Northern Force was a diversion, however: Center Force was busy pulling a 180, re-entering San Bernardino Strait to head for American beachheads at Leyte. After reports filtered in alerting Admiral Halsey to the danger posed by the remainder of Center Force, he ordered TG 38.2 to head south at full speed to intercept. The task group arrived hours too late to catch the Japanese battleships and had to wait until the next morning for their shot. Admiral Kurita had already devastated the escort carrier unit "Taffy 3" on the 25th. Through fierce combat the much smaller, thinly armored Taffys had managed to hold off the Yamatos and caused the Japanese to withdraw once more through the San Bernardino Strait. The mission of Air Group 18 on the 26th was to locate and destroy the remainder of Center Force as they were escaping back towards the Japanese home islands. Obscuring cloud cover, intense anti-aircraft fire and sheer flight distance contributed to mixed results for the air group. The initial search and subsequent strike located parts of Center Force in the Cuyo East Pass off the western coast of Panay. The bombers of VB-18 seriously damaged a Kongō-class battlecruiser and torpedoed a Nagato-class battleship in addition to doing slight damage to a number of other vessels. A third sortie failed to locate Kurita's forces and returned to "Intrepid" empty-handed, save a Tojo shot down by one of VF-18's top scorers, Charles M. Mallory. This was something of a letdown for the pilots of Air Group 18, but they were still proud of their results at Leyte: five strikes against two separate Japanese forces causing serious damage to both and leading to the sinking of carriers and one of the largest battleships ever constructed.[61][62]

Though Air Group 18 pilots put in a 9–10 hour day on the 26th and to this point had been fighting continuously for almost two months, they received no respite and were sent out on strikes against Clark Field on 29 October. The first fighter sweep of the day brought fifteen VF-18 planes to Manila Bay where they encountered heavy anti-aircraft fire from destroyers and cruisers. After bombing/strafing runs, one cruiser north of Cavite was left burning fiercely and a destroyer to the west was likely dealt serious damage. Next up, Strike 2A headed for Clark Field and there encountered many Japanese planes flying protective cover over their base. Part of VF-18 served as high cover while the remainder followed on the heels of the bomber squadrons, intent on dropping their payloads on target. As the fighters flew down to release height, they were intercepted by 15–20 enemy fighters who had been hiding in the overcast to the east of the field. Further bandits appeared on the scene also heading in from the east, bringing the total number of engaging enemies to as many as 50. Despite the swarm of enemy airplanes and moderate anti-aircraft fire, VF-18 accounted for 8 kills and only lost two pilots after the fact due to the shot-up condition of their planes. One was seen in his life raft off the Luzon coast, but Arthur "Art" Mollenhauer was nowhere to be found.[63]

Just before the second strike was set to take off, a flaming Val dove on Intrepid and crashed headlong into Gun Tub #10, immediately killing 10 men and injuring 6 more.[64] It was the first kamikaze to hit Intrepid but unfortunately would not be the last. The damage done did not impact the flight deck, though, and it was not long until the next sortie was launched from Intrepid. On Strike 2B the air group was once again received by a slew of Japanese fighters. VF-18 did "a sterling job" protecting the vulnerable bombers and in the process destroyed 11 enemy planes, accounting for many more damaged and chased away. Not a single Intrepid fighter was lost during the fight and the bombers were able to destroy a large hangar, a repair facility and did considerable damage to grounded aircraft.[65]

Cecil Harris led one of three groups of fighter escorts on the third strike, Strike 2C. The fighter groups were organized with six planes at high cover (16,000 feet (4,900 m)), three at intermediate cover and four flying low cover. After VB and VT made their runs, the low cover team dove to 7,000 feet (2,100 m) to follow the bombers on retirement, protecting them from possible enemy harassment. Seeing much game on the ground and no incoming bandits, high cover flew down to strafe aircraft sitting on the field. This left the three-man group at intermediate cover—flying at 15,000 feet (4,600 m)—properly positioned to see three Tojo fighters coming in from above and behind the rest of the strike formation. Before the Tojos could surprise the American bombers, Harris sprung in from high on their 6 o'clock, riddling one plane's cockpit and engine with bullets. This quick kill caused the other two Tojos in the division to sprint off into the clouds. With that threat neutralized, intermediate cover circled the field and stumbled upon three more Tojos at even lower altitude. Again approaching from above and behind, Harris shot down another Tojo. Again the other two Japanese pilots thought better of it and ducked behind the closest cloud. By this time the intermediate and high cover groups had convened at around 7,000 feet (2,100 m) , the bombers were at 3,000 feet (910 m) and low cover was just below them. The lack of a true high cover group proved problematic when dozens of enemy aircraft appeared at 12,000 feet (3,700 m)–19,000 feet (5,800 m). These did not seem interested in the bombers: they went straight after the fighter escort, using superior height to their advantage. In spite of solid tactical flying from the Japanese and an early disadvantage in height for the Americans, the Intrepid fighters claimed at least 10 more enemy aircraft including 2 more for Harris, bringing his total for the day to 4. Only two of VF-18's Hellcats received minor damage; none were lost.[66]

By day's end, Air Group 18 accounted for 40 enemy aircraft destroyed.[67] Cecil Harris would later be awarded the Navy Cross for exhibiting extraordinary heroism during the day's events.[23]

November

Task Group 38.2 remained off the eastern coast of Luzon for the first week of November providing continued support to US Army forces at Leyte.[68] On 5–6 November 1944, Air Group 18 flew sorties against airfields and shipping on southern Luzon.[69] Fighters participated in strafing runs far more often than they engaged in aerial combat. Out of a total of 194 sorties flown by the air group over these two days, two airborne aircraft were destroyed compared with fifty-five on the ground.[70] By now Japan was reeling from the effects of Operation Cartwheel, which had deprived it of fuel needed to get planes off the ground. Its air force was also short on experienced and even freshly-trained pilots, who were lost in huge numbers in conflicts like the Battle of the Philippine Sea,[71] and it lacked an effective seagoing navy since the back of the IJN had been broken at the Battle of Leyte Gulf.[72] This, in tandem with a week spent refueling, rearming and re-provisioning at Ulithi between 7 and 14 November, limited opportunities for Harris to further run up his score.[73]

Intrepid steamed from Ulithi back to the Philippines with orders to strike Nichols and Nielsen airfields, destroy shipping in Manila Bay and attack any concentrations of enemy aircraft encountered between Manila and Batangas. This effort began on 19 November. The first strike of the day ran into token resistance from a handful of Zekes, but these did not press home attacks on VB or VT squadrons. Instead, VF-18 fighters chased down the four Japanese aircraft, destroying two and damaging a third before disengaging to return to escort duty. Separately, a lone Zeke flying at high altitude was spotted by Cecil Harris, who led his division in a chase. Harris put a burst through the Zeke's starboard wing root from long range. As the Intrepid fighters drew nearer, the Japanese pilot bailed out. His plane continued flying for four or five minutes before the amused Hellcats flying alongside finally strafed it.[74] Back aboard Intrepid the mood was not so light. From the pre-dawn hours through the evening Japanese aircraft repeatedly tested the task group's defenses, setting off general quarters alarms and requiring emergency action to be taken all throughout the ship.[75]

Post-war

As a member of the United States Naval Reserve Cecil Harris' commission effectively ended with the War. Upon returning home, he picked up where he left off before the war, completing his degree from Northern State Teachers College and resumed his teaching career, this time at Cresbard High School where he functioned variously as principal, coach and teacher. He also was engaged to his sweetheart Eva at this time.[76]

Harris was recalled from reserve status to active duty with the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950. On 15 October 1951, Harris reported to NAS Memphis for a two-month pilot refresher training before being assigned to NAS Pensacola for flight duty.[77] Following this post, Harris served in the Air Warfare Division of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OpNav) at The Pentagon. After the Korean War he moved through a number of positions at different Naval Air Stations. He ultimately attained the rank of captain and finished out his career in the Navy back at OpNav, this time as Head of the Aviation Periodicals and History Office. Harris retired 1 July 1967.[7]

Death

Harris was driving his truck home on the evening of December 1, 1981 when he was pulled over by police. Though no bottles or cans were reportedly found in the vehicle, a Breathalyzer test returned a blood alcohol reading of .16%, leading to his arrest. Harris told an arresting officer at the scene that "if he failed the test, that was the end of his life." Family members went to the Groveton, Virginia jail where Harris was being held and attempted to have him released into their custody. Their request was denied by a local magistrate. Just past midnight on December 2 Cecil Harris was found dead in his cell, apparently having hung himself in the interim. It was his 65th birthday.[78][79]

Awards and decorations

Harris received the following decorations:[80][23]

-

Navy Cross[81]

Navy Cross[81] -

Silver Star with one Gold Star

Silver Star with one Gold Star -

Distinguished Flying Cross with two Gold Stars

Distinguished Flying Cross with two Gold Stars -

Air Medal[82][83] with two Gold Stars

Air Medal[82][83] with two Gold Stars

Recognition

On May 25, 2009, a segment of Highway 20 in South Dakota was designated the Cecil Harris Memorial Highway. Senators Johnson and Thune read their remembrances of Harris into the U.S. Congressional Record to mark the occasion.[84][85] In 2014, a statue of Harris was dedicated on the grounds of his alma mater, Northern State University.[86]

Cecil Harris's commemorative plaque aboard USS Yorktown |

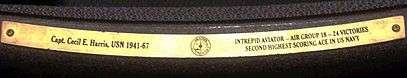

Cecil Harris's Seat of Honor in the Intrepid Museum's Lutnick |

A statue of Cecil Harris at his alma mater Northern State University, sculpted by Benjamin Victor. |

References

Citations

- ↑ Sherman 2011.

- ↑ Americanfighteraces.org, American Fighter Aces, E–K.

- ↑ Sims 1962, p. 153.

- 1 2 Tillman 1996, p. 57.

- ↑ Swisher 2015.

- ↑ The Exponent, NSTC Man Top Ace.

- 1 2 Veterantributes.org, Veteran Tributes Cecil E. Harris.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick 1942, p. 5.

- 1 2 Tillman 1996, p. 50.

- ↑ USS Cabot Muster Rolls 1944, p. 258.

- ↑ NHHC, Fighter Squadron Lineage.

- ↑ USS Intrepid Cruise Book 1945, p. 27.

- ↑ Wood 2009.

- ↑ Gandt & White 2009, p. 44.

- ↑ DeVore 1945.

- 1 2 Tillman 2012, p. 153.

- ↑ Fletcher 2012, p. 180.

- ↑ Gurney 1958, p. 99.

- 1 2 Bolger 1944d, p. 21.

- ↑ Fletcher 2012, p. 312.

- ↑ Young 2013, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Military Times, Valor Awards For Cecil Elwood Harris.

- ↑ Del Rio News Herald 1945.

- ↑ Murphy 1945.

- ↑ Pugh 1943, p. 13.

- ↑ Race 1944d, p. 23.

- ↑ Race 1944f, p. 58.

- ↑ Race 1944f, p. 146.

- ↑ Race 1944f, p. 176.

- ↑ Race 1944f, p. 197.

- ↑ Race 1944f, p. 294.

- ↑ Race 1944h, p. 2.

- ↑ Race 1944a.

- ↑ Race 1944b, p. 9.

- ↑ Race 1944b, p. 4.

- ↑ Bolger 1944a, p. 3.

- ↑ Race 1944c, p. 27.

- ↑ Coleman 1944a, p. 10.

- ↑ Race 1944c, p. 28.

- ↑ Bogan 1944a, p. 9.

- ↑ Race 1944d, p. 14.

- ↑ Race 1944d, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Bogan 1944a, p. 10.

- ↑ Race 1944e.

- ↑ Coleman 1944b, p. 10.

- ↑ Bolger 1944e, pp. 2–6.

- ↑ Race 1944f, pp. 2–6.

- ↑ Sims 1962, pp. 160–162.

- ↑ Race 1944f, pp. 58–109.

- ↑ Bogan 1944b, p. 11.

- ↑ Race 1944f, p. 144.

- ↑ Race 1944f, p. 149.

- ↑ Coleman 1944b, p. 14.

- ↑ Race 1944f, pp. 176–190.

- ↑ Mitscher 1944, p. 4.

- ↑ Coleman 1944b, p. 16.

- ↑ Race 1944f, pp. 197–236.

- ↑ Race 1944f, pp. 237–249.

- ↑ Bolger 1944b, p. 21.

- ↑ Race 1944f, pp. 254–267.

- ↑ Coleman 1944b, p. 17.

- ↑ Race 1944f, pp. 277–287.

- ↑ Bolger 1944e, p. 50.

- ↑ Race 1944f, pp. 288–293.

- ↑ Race 1944f, pp. 294–299.

- ↑ Halsey Jr. 1944, p. 2.

- ↑ Bolger 1944f, pp. 2–11.

- ↑ Race 1944g.

- ↑ Bolger 1944c, p. 19.

- ↑ Prados 2016, p. 53.

- ↑ Prados 2016, p. 336.

- ↑ Bolger 1944f, pp. 11–21.

- ↑ Race 1944h.

- ↑ Bolger 1944f, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Mason City Globe-Gazette 1945.

- ↑ The Daily Plainsman 1951.

- ↑ Shiver, Jr. 1981.

- ↑ Sun 1984.

- 1 2 National Archives 1945.

- ↑ Tillman 1997, p. 139.

- ↑ Clovis News-Journal 1945.

- ↑ Johnson 2009.

- ↑ Thune 2009, p. 173.

- ↑ Andrews 2014.

Bibliography

- Fletcher, Gregory (2012), Intrepid Aviators: The American Flyers Who Sank Japan's Greatest Battleship, Penguin Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-101-58696-9

- Gandt, Robert; White, Bill (2009), Intrepid: The Epic Story of America's Most Legendary Warship, Broadway Books, ISBN 978-0-7679-2998-1

- Gurney, Gene (1958), Five Down and Glory, Putnam

- Prados, John (2016), Storm Over Leyte: The Philippine Invasion and the Destruction of the Japanese Navy, Penguin Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-698-18576-0

- Sims, Edward (1962), Greatest Fighter Missions of the Top Navy and Marine Aces of World War II, Harper

- Tillman, Barrett (2012), Hellcat: The F6F in World War II, Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-61251-189-4

- Tillman, Barrett (1996), Hellcat Aces of World War II, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-85532-596-8

- Tillman, Barrett (1997), U.S. Navy Fighter Squadrons in World War II, Specialty Press

- Young, Edward (2013), American Aces Against the Kamikaze, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84908-746-9

Military Documents

- Bogan, Gerald F. (1944a), "Action Report, Task Group 38.2; 6 – 24 September 1944", Fold3, Ancestry.com, retrieved May 25, 2016, (subscription required (help))

- Bogan, Gerald F. (1944b), "Action Report, Task Group 38.2; 24 – 26 October 1944", Fold3, Ancestry.com, retrieved September 11, 2016, (subscription required (help))

- Bolger, Joseph F. (1944a). "Action Report, USS Intrepid, 6 – 30 September 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved September 11, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Bolger, Joseph F. (1944b). "Action Report, USS Intrepid, 10 – 31 October 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved June 3, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Bolger, Joseph F. (1944c). "Action Report, USS Intrepid, 5 – 6 November 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved June 8, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Bolger, Joseph F. (1944d). "Action Report, USS Intrepid, 14 – 27 November 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved April 23, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Bolger, Joseph F. (1944e). "War Diary, USS Intrepid, October 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved June 3, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Bolger, Joseph F. (1944f). "War Diary, USS Intrepid, November 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved June 8, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Coleman, W.M. (1944a). "War History, Air Group 18". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 25, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Coleman, W.M. (1944b). "War History, Fighting Squadron 18". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 27, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Fitzpatrick, J.F. (1942). "War Diary, Escort Squadron 27; 22 April – 1 October 1942". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 29, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Halsey Jr., William F. (1944). "Report on Operations in Support of the Leyte-Samar Operations, 27 October – 30 November 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved June 3, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Mitscher, Marc A. (1944). "Action Report, Task Force 38; 29 August – 30 October 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved September 11, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Murphy, E.J. (1945). "War History, (Reformed) Fighting Squadron 18, 1945". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 18, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Pugh, E.L. (1943). "Record of Events, Fighter Command at Guadalcanal, 1 February – 25 July 1943". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved June 10, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Race, George (1944a). "Aircraft Action Reports, Air Group 18; 6 – 8 September 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 22, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Race, George (1944b). "Aircraft Action Reports, Air Group 18; 9 – 10 September 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 22, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Race, George (1944c). "Aircraft Action Reports, Air Group 18; 12 – 14 September 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 25, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Race, George (1944d). "Aircraft Action Reports, Air Group 18; 13 – 17 September 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 27, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Race, George (1944e). "Aircraft Action Reports, Air Group 18; 21 – 22 September 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 27, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Race, George (1944f). "Aircraft Action Reports, Air Group 18; 10 – 21 October 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 29, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Race, George (1944g). "Aircraft Action Reports, Air Group 18; 5 – 6 November 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved June 8, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- Race, George (1944h). "Aircraft Action Reports, Air Group 18; 19 November 1944". Fold3. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 29, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- "Cruise Book, USS Intrepid, 1943 – 1945", Fold3, Ancestry.com, 1945, retrieved May 29, 2016, (subscription required (help))

- "Muster Rolls, USS Cabot, 1943", Fold3, Ancestry.com, November 23, 1943, retrieved May 29, 2016, (subscription required (help))

Online sources

- Andrews, John (June 17, 2014). "Cecil Harris Honored In Aberdeen". South Dakota Magazine. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- DeVore, Robert (May 19, 1945). Neely, Frederick, ed. "Wing Talk". Collier's. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- Johnson, Tim (May 20, 2009). "Remembering Cecil E. Harris". United States Senate. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

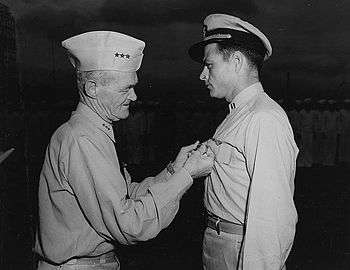

- National Archives (January 17, 1945). "VAdm. Marc A. Mitscher Presents Awards To Lieutenant Cecil E. Harris". NHHC Photographic Collections. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Olynyk, Frank. "American Fighter Aces, E–K". Americanfighteraces.org. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- Sherman, Stephen (July 2, 2011). "Intrepid Ace Cecil Harris". Acepilots.com. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- Shiver, Jr., Jube (December 4, 1981). "Family Says Police Beat Man Found Hanged". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- Sun, Lena (May 4, 1984). "Fairfax Police Cleared In Suicide At Lockup". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- Swisher, Kaija (May 22, 2015). "South Dakota's "Speedball"". Black Hills Pioneer. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- Thune, John (July 16, 2009). "Commending Cecil Harris" (PDF). United States Senate. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- Wood, Ruth (April 8, 2009). "Harris More Than War Hero". Aberdeen News. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- "Campus Statue Honors U.S. Navy Hero". NSU Veterans. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- "Fighter Squadron Lineage". NHHC. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "Navy Airmen Are Decorated". Clovis News-Journal. September 19, 1945. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- "Navy Air Ace Wants To Continue Flying". Mason City Globe-Gazette. January 17, 1945. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- Navy Cross Award (PDF), All Hands, January 1948, retrieved April 25, 2016

- "Navy's Second Ranking Ace Home On Leave". Del Rio News Herald. January 17, 1945. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- "NSTC Man Top Ace". The Exponent. December 8, 1944. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- "S.D. Teacher Recalled As Navy War Ace". The Daily Plainsman. September 30, 1951. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- Silver Star Award (PDF), All Hands, May 1947, retrieved April 25, 2016

- "Valor Awards For Cecil Elwood Harris". Military Times. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- Veteran Tributes Cecil E. Harris, Veterantributes.org, retrieved January 29, 2016