Cephalopod ink

Cephalopod ink is a dark pigment released into water by most species of cephalopod, usually as an escape mechanism. All cephalopods, with the exception of the Nautilidae and the Cirrina (deep-sea octopuses),[1] are able to release ink.

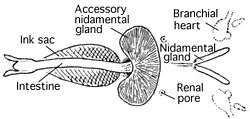

The ink is released from the ink sacs (located between the gills) and is dispersed more widely when its release is accompanied by a jet of water from the siphon. Its dark colour is caused by its main constituent, melanin. Each species of cephalopod produces slightly differently coloured inks; generally, octopuses produce black ink, squid ink is blue-black, and cuttlefish ink is a shade of brown.

A number of other aquatic molluscs have similar responses to attack, including the gastropod clade known as sea hares.

Inking behaviours

I was much interested, on several occasions, by watching the habits of an Octopus or cuttle-fish ... they darted tail first, with the rapidity of an arrow, from one side of the pool to the other, at the same instant discolouring the water with a dark chestnut-brown ink.

Two distinct behaviours have been observed in inking cephalopods. The first is the release of large amounts of ink into the water by the cephalopod in order to create a dark, diffuse cloud (much like a smoke screen) that can obscure the predator's view, allowing the cephalopod to make a rapid retreat by jetting away.

The second response to a predator is to release pseudomorphs ("false bodies"), smaller clouds of ink with a greater mucus content, which allows them to hold their shape for longer. These are expelled slightly away from the cephalopod in question, which will often release several pseudomorphs and change colour (blanch) in conjunction with these releases. The pseudomorphs are roughly the same volume as and look similar to the cephalopod that released them, and many predators have been observed attacking them mistakenly, allowing the cephalopod to escape (this behaviour is often referred to as the "blanch-ink-jet manoeuvre").

Furthermore, green turtle (Chelonia mydas) hatchlings that have been observed mistakenly attacking pseudomorphs released by Octopus bocki have subsequently ignored conspecific octopuses.[2]

However, many cephalopod predators (for instance moray eels) have advanced chemosensory systems, and some anecdotal evidence[3] suggests that compounds (such as tyrosinase) found in cephalopod ink can irritate, numb or even deactivate such apparatus. Unfortunately, few controlled experiments have been conducted to substantiate this. Cephalopod ink is nonetheless generally thought to be more sophisticated than a simple "smoke screen"; the ink of a number of squid and cuttlefish has been shown to function as a conspecific chemical alarm.[4]

Octopuses have also been observed squirting ink at snails or crabs approaching their eggs.[4]

Chemical composition

Cephalopod ink contains a number of chemicals in a variety of different concentrations, depending on the species. However, its main constituents are melanin and mucus. It can also contain, among other things, tyrosinase, dopamine and L-DOPA,[5] as well as small amounts of free amino acids, including taurine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid, alanine and lysine.[4]

Protective mechanisms

Cephalopod inking in the sea hare Aplysia californica provides protection from spiny lobsters, a major predator of sea hares, by means of three mechanisms:[6]

- chemical deterrence,

- sensory disruption, and

- phagomimicry.

The typical defence response of the sea hare to a predator is the release of chemicals such as free amino acids, ink from the ink gland and opaline from the opaline gland. Chemical deterrence involves the release of toxic chemicals that are noxious to predators and rapidly dissuades them from feeding. Ink creates a dark, diffuse cloud in the water that disrupts the sensory perception of the predator by acting as a smoke screen and as a decoy. The opaline, which affects the senses dealing with feeding, causes the predator to instinctively attack the cloud of chemicals as if it were indeed food.[6][7]

Use by humans

Cephalopod ink has, as its name suggests, been used in the past as ink; indeed, the Greek name for cuttlefish, and the taxonomic name of a cuttlefish genus, Sepia, is associated with the brown colour of cuttlefish ink (for more information, see sepia). Modern use of cephalopod ink is generally limited to cooking, where it is used as a food colouring and flavouring, for example in pasta and sauces. For this purpose it is generally obtainable from fishmongers or gourmet food suppliers. The ink is extracted from the ink sacs during preparation of the dead cephalopod, usually squid, and therefore contains no mucus.

Recent studies have shown that cephalopod ink is toxic to some cells, including tumor cells.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Roger T. Hanlon, John B. Messenger: Cephalopod Behaviour, page 2. Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-64583-2

- ↑ Roy L. Caldwell (2005), "An Observation of Inking Behavior Protecting Adult Octopus bocki from Predation by Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) Hatchlings" http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/pacific_science/v059/59.1caldwell.pdf

- ↑ G.E. MacGinitie, N. MacGinitie (1968) Natural History of Marine Animals, Pages 395-397, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- 1 2 3 4 Charles D. Derby (2007), "Escape by Inking and Secreting: Marine Molluscs Avoid Predators Through a Rich Array of Chemicals and Mechanisms" http://www.biolbull.org/cgi/reprint/213/3/274.pdf

- ↑ http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Animals/Invertebrates/Facts/cephalopods/inking.cfm

- 1 2 Derby, Charles D.; Kicklighter, Cynthia E.; Johnson, P. M. & Xu Zhang (29 March 2007). "Chemical Composition of Inks of Diverse Marine Molluscs Suggests Convergent Chemical Defenses" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2007 (33): 1105–1113. doi:10.1007/s10886-007-9279-0. Archived from the original on 15 November 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ Inman, Mason (29 March 2005). "Sea Hares Lose Their Lunch". Sciencemag.org. Retrieved 10 May 2015.