Checua

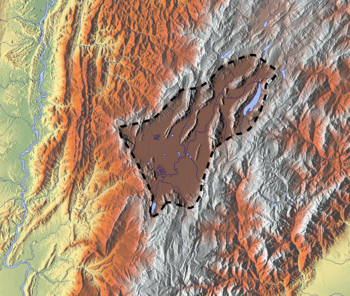

Location within Colombia | |

| Location | Nemocón, Cundinamarca |

|---|---|

| Region |

Bogotá savanna Altiplano Cundiboyacense |

| Coordinates | 5°07′12.1″N 73°52′35.3″W / 5.120028°N 73.876472°W |

| Altitude | 2,577 m (8,455 ft)[1] |

| Type | Open area settlement |

| Part of | Pre-Muisca sites |

| History | |

| Periods | Preceramic |

| Cultures | Preceramic |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Ana María Groot[2] |

Checua is a preceramic open area archaeological site in Nemocón, Cundinamarca, Colombia. The site is located 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) north of the town centre.[2][3] At Checua, thousands of stone and bone tools, stone flakes and human remains have been found, indicating human occupation from around 8500 to 3000 years BP.

Main archaeologist for Checua is Ana María Groot, who published the results of her research in 1992.[4]

Background

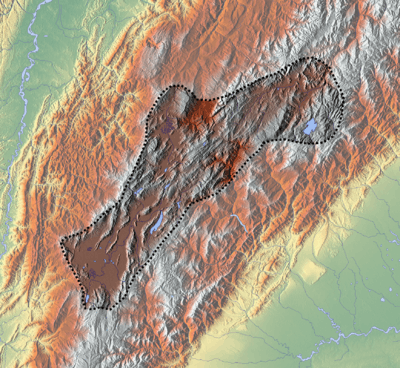

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense has been inhabited at least since 12,500 years ago. The first human settlers migrated via the Darien Gap from Central America to South America and led a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. They populated the rock shelters of the high plateau in the Andes, then still with abundant Pleistocene megafauna as Cuvieronius, Haplomastodon, Equus amerhippus and giant sloths.

During this preceramic phase, the population shifted from rock shelters to open area settlement, of which Galindo and Checua are among the oldest. A later site in Soacha, Cundinamarca; Aguazuque is comparable to Checua.

During the second millennium before present, the population increased and settlements became bigger. This is evidenced in the findings at the salt mine of Nemocón.[5]

Description

Geology

Checua is located in a valley of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense and its geology is determined by the Andean orogeny. Checua lies in the middle of a rich halite area, with salt mines in Nemocón, Zipaquirá and Tausa surrounding the site. The sedimentary sequence is shown to the right; the oldest outcropping layer is the Villeta Formation of Early Cretaceous age. This is followed by the sandstones of the Guadalupe Formation, Late Cretaceous in age. Overlying the Mesozoic section is the Eocene Guaduas Formation. Due to the Andean tectonic movements, most of the Tertiary section is eroded or non-deposited and the Guaduas Formation is overlain by the Pleistocene Sabana Formation.[6]

Climate

The climate of the area around Checua is constant throughout the year with an average maximum temperature of 21.9 °C (71.4 °F) and an average minimum of 3.05 °C (37.49 °F). The yearly precipitation varies from 600 millimetres (24 in) to 750 millimetres (30 in), mostly in short erosional showers. The winds can be strong and aid the erosive process of the water.[7]

Vegetation

The vegetation s of aa lower altitude dry forest type with native species Dodanae viscosa, Baccharis sp., Prunus capuli, Xilosma speculiferum, Duratana mutissi, Lupinus sp., dividivi (Tara spinosa), Solanum sp., Hesperolemes heterophyla and fique (Agave sp.).[8]

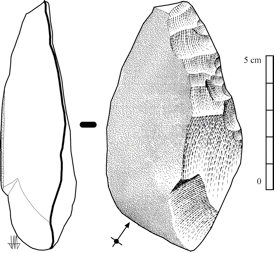

Stone tools

The Checua site has been divided into nine stratigraphical units of sands and clays.[9] More than 1750 lithic tools have been found in the units, with a highest frequency in units 4 and 5b. They mostly consist of scrapers and knives. Furthermore, 2820 stone flakes, interpreted as materials to build tools have been discovered, with a highest frequency in unit 8.[10]

Bone tools

Various bone tools have been found in Checua. The type is very similar to those found at Aguazuque and Tequendama. Apart from tools, also a musical instrument made from bone has been uncovered. This bone flute was discovered in stratigraphic unit 5b at a depth of 60 centimetres (2.0 ft).[11]

Tooth enamel

Dating of the tooth enamel of one of the remains, using Electronic Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR), provided an age of 7850 ± 190 years BP.[12] Using the same method, in 2014 another tooth enamel was analysed, providing an age of 5021 ± 202 years BP.[13]

Human occupation phases

Analysis of the various stratigraphic levels and the tools found, led to the identification of four zones of human occupation within a total time span of 5500 years (6500-1000 years BCE).[14] The first zone, dated to about 8500 to 8200 years BP, contains mostly scrapers and perforators used for the elaboration of meat and animal skins. The second zone of occupation, lasting from about 8200 to 7800 years BP, consists of various burial sites.[15] Here, also scrapers and perforators were found, together with the main ingredients of the diet of the people; white tailed deer and guinea pig.[16] In this zone, the bone flute has been unearthed.[17] The third level corresponds to the seventh stratigraphical unit where many bone fragments were found. The unit has been compared to Aguazuque for dating at around 5000 years BP, possibly lasting till 4000 years BP.[18] As is the case with Aguazuque, the fourth and uppermost zone has been disturbed by modern agricultural activities and the presence of glass indicates contamination with postcolonial influence. A top age for the sequence has not been provided, but an occupation until 3000 years BP is suggested.[19]

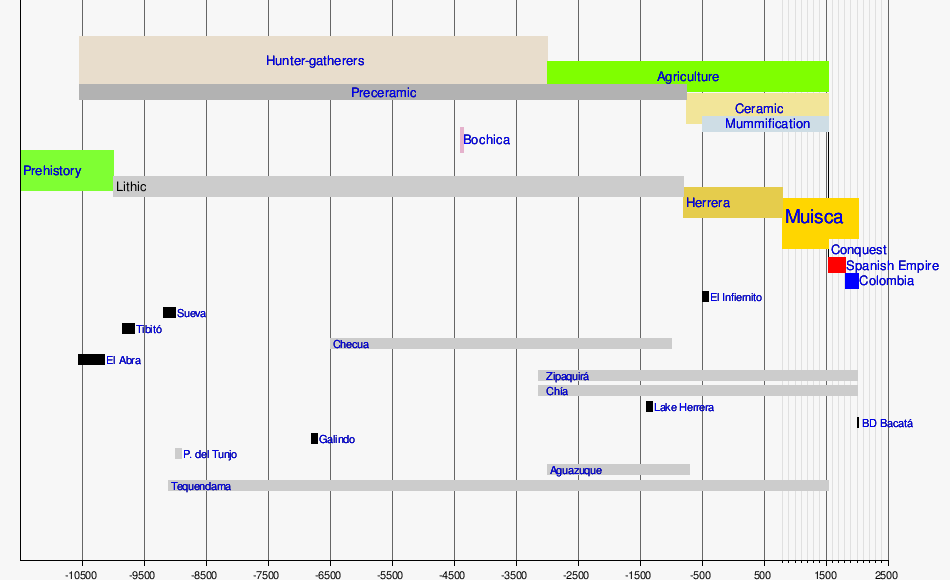

| Timeline of inhabitation of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia | |

|

.png) |

See also

References

- ↑ Google Maps Elevation Finder

- 1 2 Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.9

- ↑ Gómez Mejía, 2012, p.146

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.7

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.11

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.12

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.13

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.17

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.28

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.56

- ↑ Sandoval & Almanza, 2012, p.251

- ↑ Carvajal et al., 2014, p.128

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.61

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.64-77

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.66

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.76

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.80

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.83

Bibliography

- Carvajal, Eduar; Luis Montes, and Ovidio A. Almanza. 2014. Datación de restos arqueológicos encontrados en Checua (Cundinamarca - Colombia) mediante resonancia paramagnética electrónica. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. 38. 124-129.

- Gómez Mejía, Juliana. 2012. Análisis de marcadores óseos de estrés en poblaciones del Holoceno Medio y Tardío incial de la sabana de Bogotá, Colombia - Analysis of bone stress markers in populations of the Middle and Late Holocene of the Bogotá savanna, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Antropología 48. 143-168.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 1992. Checua: Una secuencia cultural entre 8500 y 3000 años antes del presente - Checua: a cultural sequence between 8500 and 3000 years before present, 1-95. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Sandoval, J.A., and O. Almanza. 2012. Datación de esmalte dental prehispánico proveniente del sitio arqueológico Checua (Cundinamarca) por resonancia paramagnética electrónica (EPR) - Dating of Tooth Enamel from the Archeological Site Checua (Cundinamarca) by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR). Revista Colombiana de Física 44. 248-252.

Further reading

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 1990. Aguazuque: Evidence of hunter-gatherers and growers on the high plains of the Eastern Ranges, 1-316. Banco de la República: Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 2014 (2008). Sal y poder en el altiplano de Bogotá, 1537-1640, 1-174. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.