Clonorchis sinensis

| Clonorchis sinensis | |

|---|---|

| |

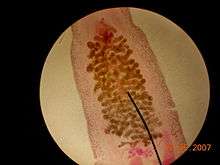

| Clonorchis sinensis under a light microscope. Notice the ovaries. This species is monoecious | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Trematoda |

| Order: | Opisthorchiida |

| Family: | Opisthorchiidae |

| Genus: | Clonorchis |

| Species: | C. sinensis Looss, 1907 |

Clonorchis sinensis, the Chinese liver fluke, is a human liver fluke in the class Trematoda, phylum Platyhelminthes. This parasite lives in the liver of humans, and is found mainly in the common bile duct and gall bladder, feeding on bile. These animals, which are believed to be the third most prevalent worm parasite in the world, are endemic to Japan, China, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia, currently infecting an estimated 30,000,000 humans.[1] 85% of cases are found in China.

It is the most prevalent human trematode in Asia, and still actively transmitted in Korea, China, Vietnam and also Russia, with 200 million people at constant risk. Recent studies have proved that it is capable of causing cancer of liver and bile duct, and in fact the International Agency for Research on Cancer has classed it as a group 1 biological carcinogen in 2009.[2][3][4]

Life cycle

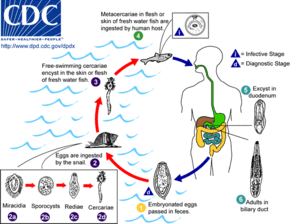

The eggs of a C. sinensis, which contain the miracidium that develops into the adult form, float in fresh water until eaten by a snail.

First intermediate host

Freshwater snail Parafossarulus manchouricus - synonym: Parafossarulus striatulus, often serves as a first intermediate host for C. sinensis in China, Japan, Korea and Russia.[5][6]

Other snail hosts include:

- Bithynia longicornis - synonym: Alocinma longicornis - in China[6]

- Bithynia fuchsiana - in China[6]

- Bithynia misella - in China[6]

- Parafossarulus anomalospiralis - in China[6]

- Melanoides tuberculata - in China[6]

- Semisulcospira libertina - in China[6]

- Assiminea lutea - in China[6]

- Tarebia granifera - in Taiwan

Once inside of the snail body, the miracidium hatches from the egg, and parasitically grows inside of the snail. The miracidium develops into a sporocyst, which in turn house the asexual reproduction of redia, the next stage. The redia themselves house the asexual reproduction of free-swimming cercaria. This system of asexual reproduction allows for an exponential multiplication of cercaria individuals from one miracidium. This aids the Clonorchis in reproduction, because it enables the miracidium to capitalize on one chance occasion of passively being eaten by a snail before the egg dies.

Once the redia mature, having grown inside the snail body until this point, they actively bore out of the snail body into the freshwater environment.

Second intermediate host

There, instead of waiting to be consumed by a host (as is the case in their egg stage), they seek out a fish. Boring their way into the fish's body, they again become parasites of their new hosts.

Once inside of the fish muscle, the cercaria create a protective metacercarial cyst with which to encapsulate their bodies. This protective cyst proves useful when the fish muscle is consumed by a human.

The second intermediate hosts are freshwater fish: Common carp (Cyprinus carpio), grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus), crucian carp (Carassius carassius), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Pseudorasbora parva, Abbottina rivularis, Hemiculter spp., Opsariichthys spp., Rhodeus spp., Sarcocheilichthys spp., Zacco platypus, Nipponocypris temminckii , and pond smelt (Hypomesus olidus).[7]

Definitive host

The acid-resistant cyst enables the metacercaria to avoid being digested by the human gastric acids, and allows the metacercaria to reach the small intestine unharmed. Reaching the small intestines, the metacercaria navigate toward the human liver, which becomes its final habitat. Clonorchis feed on human blood. In the human liver, the mature Clonorchis reaches its stage of sexual reproduction, in which it produces eggs every 1–30 seconds.

The definitive hosts are fish-eating mammals such as dogs, cats, rats, pigs, badgers, weasels, camels, and buffaloes.[7]

Effects on human health

Dwelling in the bile ducts, Clonorchis induces an inflammatory reaction, epithelial hyperplasia and sometimes even cholangiocarcinoma, the incidence of which is raised in fluke-infested areas.[8]

One adverse effect of Clonorchis is the possibility for the adult metacercaria to consume all bile created in the liver, which would inhibit the host human from digesting, especially fats. Another possibility is obstruction of the bile duct by the parasite or its eggs, leading to biliary obstruction and cholangitis (specifically oriental cholangitis).

Unusual cases of liver abscesses due to clonorchiasis have been reported. Liver abscesses may be seen even without dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts.[9]

In a report by Dr. John Chiao-nan Chang, M.D. and Dr. Yin-Ping Wang, M.D. entitled, Central Serous Retinopathy (CSR), 80 cases were studied in Hong Kong. On page 125 of their report, it was observed that 19% of the cases of CSR in their sample tested positive for Clonorchis sinensis.[10]

Symptoms

While normally asymptomatic most pathological manifestations result from inflammation and intermittent obstruction of the biliary ducts. The acute phase consists of abdominal pain with associated nausea and diarrhea. Long-standing infections consist of fatigue, abdominal discomfort, anorexia, weight loss, diarrhea, and jaundice. The pathology of long-standing infections consist of bile stasis, obstruction, bacterial infections, inflammation, periductal fibrosis, and hyperplasia. Development of cholangiocarcinoma is progressive.[11]

Diagnosis and treatment

Infection is detected mainly on identification of eggs by microscopic demonstration in faeces or in duodenal aspirate. But other sophisticated methods have been developed such as ELISA, which has become the most important clinical technique. Diagnosis by detecting DNAs from eggs in faeces are also developed using PCR, real-time PCR, and LAMP, which are highly sensitive and specific. Imaging diagnosis has been studied in depth and is now widely used.[2][12] Drugs used to treat infestation include triclabendazole, praziquantel, bithionol, albendazole, levamisole and mebendazole. However, benzimidazoles are very weak as vermicide. As with other trematodes, praziquantel is the drug of choice. Lately, tribendimidine has been acknowledged as an effective and safe drug.[2][13]

See also

References

- ↑ Wu W, Qian X, Huang Y, Hong Q (2012). "A review of the control of Clonorchiasis sinensis and Taenia solium taeniasis/cysticercosis in China". Parasitology Research. 111 (5): 1879–1884. doi:10.1007/s00436-012-3152-y. PMID 23052782.

- 1 2 3 Hong ST, Fang Y (2012). "Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis, an update". Parasitology International. 61 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2011.06.007. PMID 21741496.

- ↑ Sripa B, Brindley PJ, Mulvenna J, Laha T, Smout MJ, Mairiang E, Bethony JM, Loukas A (2012). "The tumorigenic liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini--multiple pathways to cancer". Trends in Parasitology. 28 (10): 395–407. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2012.07.006. PMC 3682777

. PMID 22947297.

. PMID 22947297. - ↑ American Cancer Society (2013). "Known and Probable Human Carcinogens". cancer.org. American Cancer Society, Inc. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- ↑ Clonorchis sinensis. Web Atlas of Medical Pathology, accessed 1 April 2009

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 World Health Organization (1995). Control of Foodborne Trematode Infection. WHO Technical Report Series. 849. PDF part 1, PDF part 2. page 125-126.

- 1 2 Chai J. Y., Darwin Murrell K. & Lymbery A. J. (2005). "Fish-borne parasitic zoonoses: Status and issues". International Journal for Parasitology 35(11-12): 1233-1254. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.013.

- ↑ Kumar et al.: Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease 7E

- ↑ Jang, Yun-Jin; Byun, Jae Ho; Yoon, Seong Eon; Yu, EunSil (2007-01-01). "Hepatic Parasitic Abscess Caused by Clonorchiasis: Unusual CT Findings of Clonorchiasis". Korean Journal of Radiology. 8 (1): 70–73. doi:10.3348/kjr.2007.8.1.70. ISSN 1229-6929. PMC 2626702

. PMID 17277566.

. PMID 17277566. - ↑ Report Text

- ↑ Dr. Kuo, O. Sinensis Lecture, ATSU School of Osteopathic Medicine Arizona, June 2012

- ↑ Huang SY, Zhao GH, Fu BQ, Xu MJ, Wang CR, Wu SM, Zou FC, Zhu XQ (2012). "Genomics and molecular genetics of Clonorchis sinensis: current status and perspectives". Parasitology International. 61 (1): 71–76. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2011.06.008. PMID 21704726.

- ↑ Xu LL, Xue J, Zhang YN, Qiang HQ, Xiao SH (2011). "In vitro effect of seven anthelmintic agents against adult Clonorchis sinensis". Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 29 (1): 10–15. PMID 21823316.

Further reading

- Freeman, Scott (2002). Biological Science. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0130932051.

- Gilbertson, Lance (1999). Zoology Laboratory Manual (Fourth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clonorchis sinensis. |

- WHO

- Animal Diversity Web

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Encyclopedia of Life

- Discovery of Clonorchis Sinensis

- Centre for Food Safety

- Video of Clonorchis sinensis infestation in the Images in Clinical Medicine section of the New England Journal of Medicine, April 17, 2008