Constitution of Bhutan

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Bhutan |

|

The Constitution of Bhutan (Dzongkha: འབྲུག་གི་རྩ་ཁྲིམས་ཆེན་མོ་; Wylie: 'Druk-gi cha-thrims-chen-mo) was enacted 18 July 2008 by the Royal Government of Bhutan. The Constitution was thoroughly planned by several government officers and agencies over a period of almost seven years amid increasing democratic reforms in Bhutan. The current Constitution is based on Buddhist philosophy, international Conventions on Human Rights, comparative analysis of 20 other modern constitutions, public opinion, and existing laws, authorities, and precedents.[1] According to Princess Sonam Wangchuck, the constitutional committee was particularly influenced by the Constitution of South Africa because of its strong protection of human rights.[2]

Background

On 4 September 2001, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck briefed the Lhengye Zhungtshog (Council of Ministers, or Cabinet), the Chief Justice, and the Chairman of the Royal Advisory Council on the need to draft a formal Constitution for the Kingdom of Bhutan. The King expressed his desire that the Lhengye Zhungtshog and the Chief Justice should hold discussions on formulating the Draft Constitution.[3] While Bhutan did not have a formal Constitution, the King believed all the principles and provisions of a Constitution were covered under the various written laws and legislation which guided the actions of the King and the functioning of the Royal Government, the judiciary and the National Assembly of Bhutan. Nevertheless, with the country and the people having successfully achieved a high level of development and political maturity, the time had come for a formal Constitution for the Kingdom of Bhutan.[3]

The King emphasized that the Constitution must promote and protect the present as well as the future well-being of the people and the country. He stated the Constitution must ensure that Bhutan had a political system that would provide peace and stability, and also strengthen and safeguard Bhutan's security and sovereignty. The King decided the Lhengye Zhungtshog should, therefore, establish a committee to draft the Constitution for the Kingdom of Bhutan. The King said that the Drafting Committee should comprise government officials, National Assembly members, and eminent citizens who were well qualified, had a good understanding of the laws of Bhutan, and who would be able to contribute towards drafting the Constitution.[3]

On November 30, 2001, the King inaugurated the outset of its drafting with a ceremony.[4] By 2005, the Royal Government had circulated copies of the draft among the civil service and local governments in order to receive locals' feedback.[5]

Provisions of the Constitution of Bhutan

The provisions of the Constitution of Bhutan appear below, grouped into thematic order for the convenience of the reader.

Basic provisions

The Constitution defines the Kingdom of Bhutan as a democratic constitutional monarchy belonging to the people of the Kingdom. The territory of Bhutan is divided into 20 Dzongkhags (Districts) with each consisting of Gewogs (Counties) and Thromdes (Municipalities). Dzongkha is the national language of Bhutan,[6] and the National Day of Bhutan is December 17.[7]

The Constitution is the supreme law of the State and affirms the authority of legal precedent:

All laws in force in the territory of Bhutan at the time of adopting this Constitution continues until altered, repealed or amended by Parliament. However, the provisions of any law, whether made before or after the coming into force of this Constitution, which are inconsistent with this Constitution, shall be null and void.[7]

The Supreme Court of Bhutan is the guardian of the Constitution and the final authority on its interpretation.[7]

Rights over natural resources vest in the State and are thus properties of the State and regulated by law.[7]

Throughout the Constitution, retirement is mandated for most civil servants upon reaching age 65.[8][9][10][11][12][13] Notably, this includes the reigning King whenever possible.[14]

The monarchy and the royal family

.jpg)

The Constitution confirms the institution of monarchy. The Druk Gyalpo (King of Bhutan) is the Head of State and the symbol of unity of the Kingdom and of the people of Bhutan. The Constitution establishes the "Chhoe-sid-nyi" (dual system of religion and politics) of Bhutan as unified in the person of the King who, as a Buddhist, is the upholder of the Chhoe-sid (religion and politics; temporal and secular).[14] In addition, the King is the protector of all religions in Bhutan.[15] The King is also the Supreme Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces and the Militia of Bhutan.[16] The King is not answerable in a court of law for his actions, and his person is sacrosanct.[14] However, the King is mandated to protect and uphold the Constitution "in the best interest and for the welfare of the people of Bhutan." Furthermore, there are Constitutional provisions for involuntary abdication in the event the King violates the Constitution.[14]

The Constitution entitles the King and the royal family to annuities from the State in accordance with law made by Parliament; all rights and privileges including the provision of palaces and residences for official and personal use; and exemption from taxation on the royal annuity and properties. The Constitution also limits the membership of the royal family to reigning and past Monarchs, their Queens and their Royal Children born of lawful marriage.[14]

Article 2 Section 26 states that Parliament may make no laws nor exercise its powers to amend the provisions regarding the monarchy and Bhutan's government as a "Democratic Constitutional Monarchy" except through a national referendum.[14]

Royal prerogatives

Under the Constitution, the King, in exercise of his Royal Prerogatives (and as Head of State), promotes goodwill and good relations with other countries by receiving state guests and undertaking state visits to other countries. The King may also award titles, decorations, dar for Lhengye and Nyi-Kyelma (conferring a red scarf of rank and honour with the title of "Dasho") in accordance with tradition and custom. Also among the Royal Prerogatives are the grants of citizenship, amnesty, pardon and reduction of sentences; and land "kidu" and other "kidus" (benefits).[14]

The King may, by Royal Prerogative, command bills and other measures to be introduced in Parliament.[14] Furthermore, bills of Parliament are ultimately subject to veto and modification by the King, however he must assent to bills resubmitted after joint sitting and deliberation.[17] The King may also exercise powers "relating to matters which are not provided for under this Constitution or other laws."[14]

Succession and retirement

The Constitution establishes the law of succession of the Golden Throne of Bhutan. Under this Section, title to the throne vests in the legitimate descendants of King Ugyen Wangchuck, enshrined on December 17, 1907. Title may pass only to children born of lawful marriage, by hereditary succession to direct lineal descendants in order of seniority upon the abdication or demise of the King. Article 2 Section 6 provides that upon reaching age 65, the King must retire (abdicate) in favor of the Crown Prince or Crown Princess, provided the royal heir has reached age 21.[14]

There is a stated preference that a prince take precedence over a princess, however this is subject to the exception that if there are "shortcomings in the elder prince, it is the sacred duty of the King to select and proclaim the most capable prince or princess as heir to the Throne." Title to the throne may also pass to the child of the Queen who is pregnant at the time of the demise of the King if no lineal heir exists. Such is an example of semi-Salic law.[14]

If there are no present or prospective lineal heirs, title passes to the nearest collateral line of the descendants of the King in accordance with the principle of lineal descent, with preference being given for elder over the younger. Title may never pass to children incapable of exercising the Royal Prerogatives by reason of physical or mental infirmity, nor to anyone whose spouse is a person other than a natural born citizen of Bhutan.[14]

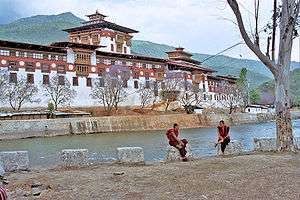

The successor to the Throne receives dar (a scarf that symbolizes the conferring of rank) from the Machhen (the holy relic) of Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal at Punakha Dzong, and is crowned on the Golden Throne. Upon the ascension of the King to the Throne, the members of the royal family, the members of Parliament, and the holders of offices requiring appointment by the King must take an oath of allegiance to the King.[14]

Regency

The Constitution provides a procedural framework for a Council of Regency. A Council of Regency is established when the King has temporarily relinquished, by Proclamation, the exercise of the Royal Prerogatives; or when it has been resolved by at least ¾ of the total number of members of Parliament in a joint sitting that the King is unable to exercise the Royal Prerogatives by reason of temporary physical or mental infirmity; or the King abdicates or dies and the successor to the throne has not attained the age 21. These provisions are effective until the royal heir presumptive reaches age 21 and becomes Regent by right.[14]

When the successor to the throne reaches age 21, or when the King resumes the exercise of the Royal Prerogatives, notice must be given by Proclamation. However, when the King regains the ability to exercise the Royal Prerogatives, notice is given to that effect by resolution of Parliament.[14]

The Council of Regency collectively exercises the Royal Prerogatives and the powers vested in the King. The Council of Regency is composed of 6 members: one senior member of the royal family nominated by the Privy Council (below), the Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of Bhutan, the Speaker, the Chairperson of the National Council, and the leader of the Opposition Party.[14]

Privy Council

The Constitution establishes a Privy Council of four persons, consisting of two members appointed by the King, one member nominated by the Lhengye Zhungtshog (Council of Ministers), and one member nominated by the National Council. The Privy Council is responsible for: all matters pertaining to the privileges and conduct of the King and the royal family; rendering advice to the King on matters concerning the Throne and the royal family; all matters pertaining to crown properties; and any other matter as may be commanded by the King.[14]

Royal appointments

Under Article 2 Section 19, the King appoints a significant number of high-level Government officers: Judicial appointees, the Auditor General, and the Chairs of Anti-Corruption, Civil Service, and Election Commissions are holders of Constitutional Office.[13][14]

The King appoints most of the upper Judicial branch: the Chief Justice of Bhutan and the Drangpons (Associate Justices) of the Supreme Court; the Chief Justice and Drangpons (Associate Justices) of the High Court. These judicial appointments are made from among the vacant positions' peers, juniors, and available eminent jurists in consultation with the National Judicial Commission (below).[8][14] Dungkhag Court jurists are not appointed by the King.

The King also appoints, from lists of names recommended jointly by the Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of Bhutan, the Speaker, the Chairperson of the National Council, and the Leader of the Opposition Party, four kinds of high-level Government: the Chief Election Commissioner and other members of the Election Commission;[18] the Auditor General of the Royal Audit Authority;[10] the Chairperson and other members of the Royal Civil Service Commission;[11] and the Chairperson and other members of the Anti-Corruption Commission.[12] The term for each position is 5 years. Referenced for incorporation are the Bhutanese Audit Act, Bhutanese Civil Service Act, Bhutanese Anti-Corruption Act, and Attorney General Act; references to existing Election Laws also appear throughout the Constitution.

The King appoints positions other than Constitutional Officers on the advice of other bodies.[14] He appoints the heads of the Defence Forces from a list of names recommended by the Service Promotion Board. The King appoints the Attorney General of Bhutan,[19] the Chairperson of the Pay Commission,[20] the Governor of the Central Bank of Bhutan, the Cabinet Secretary, and Bhutanese ambassadors and consuls on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. The King also appoints Dzongdags to head Local Governments, and other secretaries to the Government on the recommendation of the Prime Minister who obtains nominations from the Royal Civil Service Commission on the basis of merit and seniority and in accordance with other relevant rules and regulations. The King appoints the Secretary General of the respective Houses on the recommendation of the Royal Civil Service Commission.

The King also appoints the Je Khenpo (below) as the spiritual leader of Bhutan.[15] Finally, as indicated above, the King appoints 2 of the 4 members of the Privy Council.[14]

Voluntary and involuntary abdication

The Constitution provides substantive and procedural law for two paths of abdication for reigning monarchs: voluntary and involuntary. As stated above, the King may relinquish the exercise of Royal Prerogatives, and such relinquishment may be temporary.

The Constitution provides that the King must abdicate the throne for willful violations of the Constitution or for suffering permanent mental disability. Either must be upon a motion passed by a joint sitting of Parliament. The motion for abdication must be tabled for discussion at a joint sitting of Parliament (presided by the Chief Justice of Bhutan) if at least ⅔ of the total number of the members of Parliament submits such a motion stating its basis and grounds. The King may respond to the motion in writing or by addressing the joint sitting of Parliament in person or through a representative.[14]

If, at such joint sitting of Parliament, at least ¾ of the total number of members of Parliament passes the motion for abdication, then such a resolution is placed before the people in a National Referendum to be approved or rejected. If the National Referendum passes in all the Dzongkhags in the Kingdom, the King must abdicate in favour of the heir apparent.

Heritage of Bhutan

Buddhism

The Constitution states that Buddhism is the spiritual heritage of Bhutan.[15] Buddhism is described as promoting the principles and values of peace, non-violence, compassion and tolerance. The Constitution places upon religious institutions and personalities the responsibility to promote the spiritual heritage of Bhutan while also ensuring that religion remains separate from politics in Bhutan.[15] Religious institutions and personalities are explicitly required to remain above politics. The sole Constitutional exception is the King under the Chhoe-sid-nyi (dual system of religion and politics).[14] Thus, while religion and politics are officially separate, the Buddhist Drukpa Lineage is the state religion of Bhutan.

The King appoints the Je Khenpo on the recommendation of the Five Lopons (teachers). The Je Khenpo must be a learned and respected monk ordained in accordance with the Druk-lu tradition, having the nine qualities of a spiritual master and accomplished in ked-dzog. The Je Khenpo appoints, on the recommendation of the Dratshang Lhentshog (Commission for the Monastic Affairs), the Five Lopons from among monks with the nine qualities of a spiritual master and accomplished in ked-dzog (stages of development and completion in Vajrayana practice). The membership of the Dratshang Lhentshog comprises 7 people: the Je Khenpo as Chairman; the Five Lopons of the Zhung Dratshang (Central Monastic Body); and the Secretary of the Dratshang Lhentshog who is a civil servant. The Zhung Dratshang and Rabdeys (monastic bodies in the dzongs other than Punakha and Thimphu) are to receive adequate funds and other facilities from the State.[15]

Culture of Bhutan

The Constitution codifies Bhutanese culture in legal terms. The State must endeavour to preserve, protect and promote the cultural heritage of the country, including monuments, places and objects of artistic or historic interest, Dzongs (fortresses), Lhakhangs (monasteries), Goendeys (monastic communities), Ten-sum (sacred images, scriptures, and stupas), Nyes (sacred pilgrimage sites), language, literature, music, visual arts and religion to enrich society and the cultural life of the citizens. It must also recognize culture as an evolving dynamic force and endeavour to strengthen and facilitate the continued evolution of traditional values and institutions that are sustainable as a progressive society. The State must conserve and encourage research on "local" arts, custom, knowledge and culture.[21]

The Constitution allows Parliament to enact any such legislation as may be necessary to advance the cause of the cultural enrichment of Bhutanese society.[21]

Article 5 pertains to the environment. The Constitution states that every Bhutanese is a trustee of the Kingdom's natural resources and environment for the benefit of the present and future generations and declares it the fundamental duty of every citizen to contribute to protection, conservation, and prevention of all forms of ecological degradation including noise, visual and physical pollution. This Article mandates the adoption and support of environment friendly practices and policies.[7][22]

The Government itself pledges to protect, conserve and improve the pristine environment and safeguard the biodiversity of the country; prevent pollution and ecological degradation; secure ecologically balanced sustainable development while promoting justifiable economic and social development; and ensure a safe and healthy environment. To this end, it promises that a minimum of 60 percent of Bhutan's total land shall be maintained as forest for all time.[22]

Parliament may enact environmental legislation to ensure sustainable use of natural resources, maintain intergenerational equity, and reaffirm the sovereign rights of the State over its own biological resources. Parliament may also declare any part of the country to be a National Park, Wildlife Reserve, Nature Reserve, Protected Forest, Biosphere Reserve, Critical Watershed and such other categories meriting protection.[22]

Citizenship

The Constitution provides three categories of citizenship. First, "natural born citizens" are children of two citizen parents. This is an ambilineal jus sanguinis citizenship law.[23]

Second, "citizens by registration" are those who can prove domicile in Bhutan by December 31, 1958 by showing registration in the official record of the Government of Bhutan.[23]

Third, "citizens by naturalization" are those who have applied for, and were granted, naturalization. Naturalization requires applicants to have lawfully resided in Bhutan for at least 15 years; have no record of imprisonment for criminal offences within the country or outside; can speak and write Dzongkha; have a good knowledge of the culture, customs, traditions and history of Bhutan; and have no record of having spoken or acted against the Tsawa-sum. They must also renounce the citizenship, if any, of a foreign State on being conferred Bhutanese citizenship; and take a solemn Oath of Allegiance to the Constitution as may be prescribed. The grant of citizenship by naturalization takes effect by a Royal Kasho (written order) of the King.[23]

The Constitution prohibits dual citizenship. If citizens of Bhutan acquire another citizenship, their Bhutanese citizenship is terminated.[23]

The Constitution confers the power to regulate all matters relating to citizenship to Parliament, subject to the Citizenship Acts.[23]

Fundamental rights

The Constitution, in Article 7, guarantees a number of Fundamental Rights, variously to all persons and to citizens of Bhutan.[24]

All persons have the right to life, liberty and security of person and is not deprived of such rights except in accordance with the due process of law.[24]

All persons in Bhutan have the right to material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he or she is the author or creator.[24]

All persons are equal before the law and are entitled to equal and effective protection of the law. They must not be discriminated against on the grounds of race, sex, language, religion, politics or other status.[24] (Cf. American Equal Protection Clause).

All persons are guaranteed freedom from torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; capital punishment; arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy, family, home or correspondence; arbitrary arrest or detention; and from unlawful attacks on the person's honour and reputation.[24]

No person may be compelled to belong to another faith by means of coercion or inducement. See freedom of religion in Bhutan.

No person may be deprived of property by acquisition or requisition, except for public purpose and on payment of fair compensation in accordance with the provisions of the law. (Cf. Common Law concepts of "eminent domain" and "just compensation.")

Persons charged with a penal offence are presumed innocent until proven guilty in accordance with the law. This is an explicit statement of the presumption of innocence. All persons have the right to consult and be represented by a Bhutanese jabmi (attorney) of their choice (right to counsel).

Bhutanese citizens have the right to freedom of speech, opinion and expression; the right to information; the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; the right to vote; the right to freedom of movement and residence within Bhutan; the right to equal access and opportunity to join the Public Service; the right to own property (but not the right to sell or transfer land or any immovable property to non-citizens, except as allowed by Parliament); the right to practice any lawful trade, profession or vocation; the right to equal pay for work of equal value; the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of association, other than membership of associations that are harmful to the peace and unity of the country; and the right not to be compelled to belong to any association.

The Constitution guarantees freedom of the press, radio and television and other forms of dissemination of information, including electronic.

However, the State may subject persons to reasonable restriction by law, when it concerns the interests of the sovereignty, security, unity and integrity of Bhutan; the interests of peace, stability and well-being of the nation; the interests of friendly relations with foreign States; incitement to an offence on the grounds of race, sex, language, religion or region; the disclosure of information received in regard to the affairs of the State or in discharge of official duties; or the rights and freedom of others.

All persons in Bhutan have the right to initiate appropriate proceedings in the Supreme Court or High Court for the enforcement of the rights conferred by Article 7, subject to the above reasonable restriction by law.

Fundamental duties

Article 8 of the Constitution defines Fundamental Duties in Bhutan. All persons must respect the National Flag and the National Anthem. No persons may tolerate or participate in acts of injury, torture or killing of another person, terrorism, abuse of women, children or any other person, and must take necessary steps to prevent such acts. All persons have the responsibility to provide help, to the greatest possible extent, to victims of accidents and in times of natural calamity; to safeguard public property; and to pay taxes in accordance with the law. All persons have the duty to uphold justice and to act against corruption; to act in aid of the law; and to respect and abide by the provisions of the Constitution.[25]

Bhutanese citizens must preserve, protect and defend the sovereignty, territorial integrity, security and unity of Bhutan. Bhutanese citizens must render national service when called upon to do so by Parliament. They have the duty to preserve, protect and respect the environment, culture and heritage of the nation; and to foster tolerance, mutual respect and spirit of brotherhood amongst all the people of Bhutan transcending religious, linguistic, regional or sectional diversities.[25]

State policy

Article 9 defines the principles of state policy. By the language of the Constitution, some provisions of the mandate are obligatory, while others listed in Article 9 are precatory, stating that "the State shall endeavour" to fulfill certain guarantees.

Social policy

The State must provide free education to all children of school going age up to grade 10, ensure that technical and professional education is made generally available, and ensure that higher education is equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.[26] It must also provide free access to basic public health services in both modern and traditional medicines; and encourage free participation in the cultural life of the community, promote arts and sciences and foster technological innovation. The State must also encourage and foster private sector development through fair market competition and prevent commercial monopolies.[26]

The State endeavours to apply State Policy to ensure a good quality of life for the people of Bhutan in a progressive and prosperous country that is committed to peace and amity in the world. It strives to promote conditions that will enable the pursuit of Gross National Happiness.[26]

The State also endeavours to guarantee human rights. It endeavours to create a civil society free of oppression, discrimination and violence; based on the rule of law, protection of human rights and dignity. It also endeavours to ensure the right to work, vocational guidance and training and just and favourable conditions of work. It strives to provide education for the purpose of improving and increasing knowledge, values and skills of the entire population with education being directed towards the full development of the human personality. The State endeavours to take appropriate measures to eliminate all forms of discrimination and exploitation against women and children; and to promote those conditions that are conducive to co-operation in community life and the integrity of the extended family structure.[26]

The State further endeavours to ensure fundamental rights listed under Article 7; to provide justice through a fair, transparent and expeditious process; to safeguard legal aid to secure justice; and to protect the telephonic, electronic, postal or other communications of all persons in Bhutan from unlawful interception or interruption.[26] These are further guarantees of due process and privacy.

Crossing into religion, the State strives to create conditions that will enable the true and sustainable development of a good and compassionate society rooted in Buddhist ethos and universal human values.[26]

Economic policy

The Constitution declares the State's economic endeavours. The State endeavours to develop and execute policies to minimize inequalities of income, concentration of wealth, and promote equitable distribution of public facilities among individuals and people living in different parts of the Kingdom. Thus, the State's policy in carrying out its objectives is somewhat Buddhist-socialist. The State also endeavours to achieve economic self-reliance and promote open and progressive economy; to ensure the right to fair and reasonable remuneration for one's work; to ensure the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay; and to provide security in the event of sickness and disability or lack of adequate means of livelihood for reasons beyond one's control. The State also endeavours to ensure that all the Dzongkhags are treated with equity on the basis of different needs so that the allocation of national resources results in comparable socio-economic development.[26]

The Constitution defines the Government's role in finance, trade and commerce. It authorizes the Government to raise loans, make grants, or guarantee loans. It also sets up a regulatory framework for the Consolidated Fund, Bhutan's general public assets.[27]

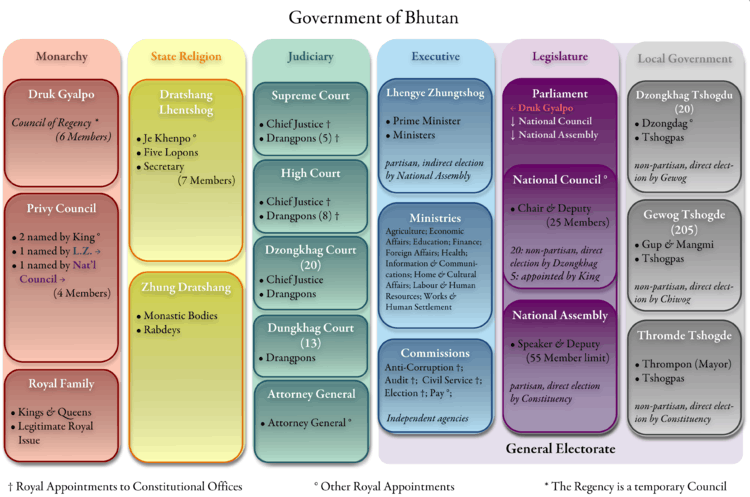

Branches of government

The Constitution mandates the separation of the legislative, executive and judicial branches except to the extent provided for by the Constitution.[7] The legislative branch is the bicameral Parliament of Bhutan. The executive branch is the Lhengye Zhungtshog (cabinet), headed by the Prime Minister and supported by subsidiary government agencies. The politically independent judicial branch is the Royal Court of Justice, which is reviewed by the Supreme Court of Bhutan. Within these branches of government, only members of the executive and the National Assembly (the lower house of Parliament) may hold political party affiliations.

Legislative branch and operation

Parliament consists of the King, the National Council and the National Assembly.[28] Bhutan's international territorial boundaries and internal Dzongkhag and Gewog divisions may be altered only with the consent of at least ¾ of the total number of members of Parliament.[7]

The National Council of Bhutan is the upper house, or house of review in the bicameral legislature. It consists of 25 members: one directly elected from each of the 20 Dzongkhags (Districts) and 5 appointed by the King. The National Council meets at least twice a year. The membership elects a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson from its number. Members and candidates of the National Council are prohibited from holding political party affiliation.[29]

The National Assembly of Bhutan is the lower house of parliament. It consists of a maximum of 55 members directly elected by the citizens of constituencies within each Dzongkhag (District). Under this system of proportional representation, each constituency is represented by one National Assembly member; each of the 20 Dzongkhags must be represented by between 2–7 members. Constituencies are reapportioned every 10 years. The National Assembly meets at least twice a year, and elects a Speaker and Deputy Speaker from among its members. Members and candidates may be members of political parties.[30]

The Constitution details procedures for the passing of bills and other procedural requirements of governance. Bhutanese legislation must be presented bicamerally, at times in joint sitting of the National Council and National Assembly, however bills may pass by default without vote when none is conducted before the close of the present session. Bills are ultimately subject to veto and modification by the King, however the King must assent to bills resubmitted after joint sitting and deliberation by the National Council and National Assembly.[17]

The National Assembly may, with support of at least ⅓ of its members, motion of no confidence in the Government. If the vote passes with at least ⅔ support, the King must dismiss the Government.[24]

The Constitution defines the rights and duties of the opposition party in Parliament.[31] It also lays a framework for the formation, function, and dissolution of interim governments.[32]

Executive

Executive power is vested in the Lhengye Zhungtshog (Council of Ministers, or Cabinet), which consists of the Ministers headed by the Prime Minister.[33]

The Constitution sets forth the procedure of the formation of government and its ministries, providing for the post of Prime Minister and the other Ministers of Bhutan. The King recognizes the leader or nominee of the party that wins the majority of seats in the National Assembly as the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is limited to two terms of office. Other Ministers are appointed from among National Assembly members by the King on advice of the Prime Minister. All Ministers must be natural-born citizens of Bhutan. There is a limit of two Ministers from any one Dzongkhag.[34]

The number of other Ministers is determined by the number of Ministries required to provide efficient and good governance. Creation of an additional ministry or reduction of any ministry must be approved by Parliament. The Lhengye Zhungtshog must aid and advise the King in the exercise of his functions as Head of State including international affairs, provided that the King may require the Lhengye Zhungtshog to reconsider such advice. The Prime Minister must keep the King informed from time to time about the affairs of the State, including international affairs, and must submit such information and files as called for by the King.[33]

The Lhengye Zhungtshog must assess the state of affairs in Government and society, at home and abroad; define the goals of State action and determine the resources required to achieve them; plan and co-ordinate government policies and ensure their implementation; and represent the Kingdom at home and abroad. The Lhengye Zhungtshog are collectively responsible to the King and to Parliament. The Executive cannot issue any executive order, circular, rule or notification inconsistent with, modifying, varying or superseding the laws of Bhutan.[33]

Judiciary

Article 21 pertains to the judiciary. The duty of the Judiciary of Bhutan is to safeguard, uphold, and administer justice fairly and independently without fear, favour, or undue delay in accordance with the rule of law to inspire trust and confidence and to enhance access to justice. The judicial authority of Bhutan is vested in the Royal Court of Justice, comprising the Supreme Court, the High Court, the Dzongkhag Courts, the Dungkhag Courts, and such other courts and tribunals as may be established by the King on the recommendation of the National Judicial Commission.[8]

The Supreme Court of Bhutan, which comprises the Chief Justice and four Drangpons, is the highest appellate authority to entertain appeals against the judgments, orders, or decisions of the High Court in all matters. The Supreme Court is a court of record. The Chief Justice of Bhutan, Drangpons (Associate Justices) of the Supreme Court are appointed by the King. The term of office of the Chief Justice of Bhutan is five years (or until attaining age 65). That of the Drangpons of the Supreme Court is ten years (or until attaining age 65). Where a question of law or fact is of such a nature and of such public importance that it is expedient to obtain the opinion of the Supreme Court, the King may refer the question to the Supreme Court for its consideration, which hears the reference and submit its opinion to him. The Supreme Court may, on its own motion or on an application made by the Attorney General or by a party to a case, withdraw any case pending before the High Court involving a substantial question of law of general importance relating to the interpretation of this Constitution and dispose off the case itself.[8]

The Chief Justice and Drangpons of the High Court of Bhutan are appointed by the King. The term of office of the Chief Justice and the Drangpons of the High Court is 10 years (or until attaining age 60). The High Court of Bhutan, which comprises a Chief Justice and eight Drangpons, is the court of appeal from the Dzongkhag Courts and Tribunals in all matters and exercises original jurisdiction in matters not within the jurisdiction of the Dzongkhag Courts and Tribunals.[8] The judges of the Dzongkhag and Dungkhag Courts are not appointed by the King.

Every person in Bhutan has the right to approach the courts in matters arising out of the Constitution or other laws subject to guarantee as fundamental rights.[8] The Supreme Court and the High Court may issue such declarations, orders, directions or writs as may be appropriate in the circumstances of each case.[8]

By command of the King and upon the recommendation of the National Judicial Commission, Drangpons of the Supreme Court and the High Court may be punished by censure and suspension for proven misbehaviour that does not deserve impeachment in the opinion of the Commission. Parliament may, by law, establish impartial and independent Administrative Tribunals as well as Alternative Dispute Resolution centres.[8]

The King appoints the four members of the National Judicial Commission. The Commission comprises the Chief Justice of Bhutan as Chairperson, the senior most Drangpon of the Supreme Court, the Chairperson of the Legislative Committee of the National Assembly, and the Attorney General.[8]

Local governments

Eastern Southern Central Western

Article 22 establishes Local Governments that are "decentralized and devolved to elected Local Governments to facilitate the direct participation of the people in the development and management of their own social, economic and environmental well-being." The stated objectives of all Local Governments are to ensure that local interests are taken into account in the national sphere of governance by providing a forum for public consideration on issues affecting the local territory; to provide democratic and accountable government for local communities; to ensure the provision of services to communities in a sustainable manner; to encourage the involvement of communities and community organizations in matters of local governance; and to discharge any other responsibilities as may be prescribed by law made by Parliament.[35]

Local Governments receive financial resources from the National Government in the form of annual grants to ensure self-reliant and self-sustaining units of local self-government and to promote holistic and integrated area-based development planning. Local Governments are entitled to levy, collect, and appropriate taxes, duties, tolls, and fees in accordance with procedures provided for by Parliament by law. Local Governments are also entitled to own assets and incur liabilities by borrowing on their own account subject to such limitations as may be provided for by Parliament by law.[35] Such is an example of a decentralized economy.

The Constitution divides Local Government into three tiers: Dzongkhag Tshogdu (District Council at the highest local level), Gewog Tshogde (County Committee at the intermediate local level) and Thromde Tshogde (Municipal Committee at the most local level). Each body sits for five-year terms.[35]

There are 20 Dzongkhags (Districts) in all of Bhutan, each headed by a Dzongdag appointed by the King as the chief executive supported by civil servants. Each Dzongkhag is also represented by a Dzongkhag Tshogdu (District Council). Membership of the Dzongkhag Tshogdu depends on the number of Gewogs within the Dzongkhag. Each Gewog is represented on the Tshogdu by two members, its Gup and Mangmi (below). Two further members of the Tshogdu are one elected representative from the Dzongkhag Thromde (District municipality) and one elected representative from Dzongkhag Yenlag Thromde (satellite towns). The Dzongkhag Tshogdu elects a Chairperson from among its members and meets at least twice a year.[35]

Dzongkhags are divided into Gewogs (Counties or Blocks), numbering 205 in all of Bhutan. These are in turn subdivided into Chiwogs for election purposes. Each Gewog is represented by a Gewog Tshogde (County Committee), headed by a Gup (Head of Gewog) and a Mangmi (deputy), both of whom are directly elected by citizens. Other Tshogpas (Representatives) are directly elected by citizens of Chiwogs. The membership of each Gewog Tshogde must comprise between 7–10 members and meet at least three times annually.[35]

On the most local level, a Thromde Tshogde (Municipal Committee) is headed by a Thrompon (Mayor), who is directly elected by the voters of the Dzongkhag Thromde. The powers and functions of the Thrompon are defined by Parliament. The other members of the Thromde Tshogde are elected directly by citizens divided into constituencies. Like the Gewog Tshogde, the Thromde Tshogde must comprise between 7–10 members and meet at least three times annually.[35]

The Constitution establishes a ⅔ quorum requirement in order to conduct any business on Local Government levels. It also defines local electoral procedure in terms of Parliamentary Electoral Laws. Notably, candidates and members of the Local Governments are banned from political party affiliation.[35]

Political parties

Article 15 sets up a regulatory framework for political parties, however the Constitution provides partisan elections only for the National Assembly. Two political parties are elected to the National Assembly, established through a primary election in which all registered political parties may participate.[36] The majority is the ruling party, while the second party among the plurality forms the opposition. Defection from one party to another is prohibited to sitting members.[36]

Political parties must promote national unity and progressive economic development and strive to ensure the well-being of the nation. Candidates and parties are prohibited from appealing to regionalism, ethnicity and religion to incite voters for electoral gain.[36]

Political parties must be registered by the Election Commission. Registration requires their members to be Bhutanese citizens and not otherwise disqualified, and that membership not be based on region, sex, language, religion or social origin. Registration requires parties be broad-based with cross-national membership and support and be committed to national cohesion and stability. Members of all parties must declare allegiance to the constitution and uphold the sovereignty, security, and unity of the Kingdom. Furthermore, parties are required to advance democracy and the social, economic, and political growth of Bhutan.[36]

Parties are prohibited from receiving any money or assistance other than those contributions made by its registered members, and the value of such contributions is regulated by the Election Commission. Parties are prohibited from receiving any money or assistance from foreign sources, be it governmental, non-governmental, private organizations or from private parties or individuals.[36]

Political parties may be dissolved only by declaration of the Supreme Court. The Constitution establishes grounds for dissolution of political parties. If party objectives or activities are in contravention of the Constitution; if a party has received money or assistance from foreign sources; or if the Election Laws are violated, the Supreme Court may declare that party dissolved. Furthermore, Parliament may proscribe other laws with the effect of disqualifying political parties. Once dissolved, political parties may not comprise any members.[36]

Parliament regulates the formation, functions, ethical standards, and intra-party organization of political parties and regularly audits their accounts to ensure compliance with law.[36]

Article 16 delineates the rules of public campaign financing.[37]

Elections

Article 23 defines the Constitutional requirements for elections in Bhutan. The Constitution calls for universal suffrage by secret ballot of all citizens over age 18 who have been registered in the civil registry of their constituency for at least one year and not "otherwise disqualified from voting under any law in force in Bhutan." In order to vote, Bhutanese citizens must furnish their Citizenship Card.[9]

Parliament makes, by law, provisions for all matters relating to, or in connection with, elections including the filing of election petitions challenging elections to Parliament and Local Governments, and the Code of Conduct for the political parties and the conduct of the election campaign as well as all other matters necessary for the due constitution of the Houses of Parliament and the Local Governments.[9]

In order to provide for informed choice by the voter, candidates for an elective office must file, along with a nomination, an affidavit declaring: the income and assets of candidates, spouses and dependent children; biographical data and educational qualifications; records of criminal convictions; and whether candidates are accused in a pending case for an offense punishable with imprisonment for more than one year and in which charges are framed or cognizance is taken by a court of law prior to the date of filing of such a nomination.[9]

To qualify for an elective office, candidates must be Bhutanese citizens; must be registered voters in their own constituencies; be between ages 25 and 65 at the time of nomination; must not receive money or assistance from foreign sources whatsoever; and fulfill the necessary educational and other qualifications prescribed in the Electoral Laws.[9]

Persons are disqualified from holding an elective office if they marry a non-citizen; have been terminated from public service; have been convicted for any criminal offense and sentenced to imprisonment; are in arrears of taxes or other dues to the Government; have failed to lodge accounts of election expenses within the time and in the manner required by law without good reason or justification; holds any office of profit under the Government, public companies, or corporations as prescribed in the Electoral Laws; or is disqualified under any law made by Parliament. Disqualifications are adjudicated by the High Court on an election petition filed pursuant to law made by Parliament.[9]

Audits and commissions

The Constitution provides for several independent government bodies analogous to agencies. Under Article 2 Section 19 (above), the King appoints the members of these agencies on advice from the civil government, namely the Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of Bhutan, the Speaker, the Chairperson of the National Council, and the Leader of the Opposition Party.[14] The term for each position is 5 years. Referenced for incorporation by respective sections are the Bhutanese Audit Act, Bhutanese Civil Service Act, and Bhutanese Anti-Corruption Act; references to existing "Election Laws" also appear throughout the Constitution.

The independent Election Commission is responsible for the preparation, maintenance, and periodical updating of electoral rolls, the election schedule, and the supervision, direction, control, and conduct of elections to Parliament and Local Governments, as well as holding of National Referendums, in a free and fair manner. It is also responsible for the delimitation of constituencies for election of the members of Parliament and Local Governments. It functions in accordance with the Electoral Laws set forth by Parliament and is headed by the Chief Election Commissioner for a term of 5 years.[18]

The Constitution codifies and explains the function of the Royal Audit Authority. The Audit Authority is tasked with auditing the accounts of all departments and offices of the Government, and wherever public funds are used including the police and defence forces. The Auditor General submits an annual report to the King, the Prime Minister and Parliament. Parliament appoints a five-member Public Accounts Committee, comprising members of Parliament who are reputed for their integrity, to review and report on the annual audit to Parliament for its consideration or on any other report presented by the Auditor General. The Royal Audit Authority functions in accordance with the Audit Act.[10]

The Constitution codifies and explains the function of the Royal Civil Service Commission. Its membership consists of one Chairman and four other members, all appointed by the King. It also comprises a Secretariat as the Government's central personnel agency. The Commission is charged with training, placing, and promoting quality civil servants within a transparent and accountable apparatus. The Constitution guarantees administrative due process safeguards, but only to civil servants. It also provides that the Commission must operate under the Civil Service Act of Parliament.[11]

The Constitution also codifies and explains the function of the Anti-Corruption Commission. It is headed by a Chairperson and comprises two members. The Commission reports to the King, the Prime Minister, and Parliament; prosecution on the basis of the findings of the Commission are undertaken by the Attorney General for adjudication by the courts. The Commission functions in accordance with Parliament's Anti-Corruption Act.[12]

Defence

The Constitution defines the role and objectives of the Bhutanese defence apparatus. The King is the Supreme Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces and the Militia. It establishes the Royal Body Guards as responsible for the security of the King. It also requires the Royal Bhutan Army to be a professional standing army to defend against security threats. The Royal Bhutan Police are trained under the Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs and are responsible for maintaining law and order and preventing crime. Parliament may require compulsory militia service for adult citizens to strengthen the defence of Bhutan. The Constitution allows the Government to use military force against foreign states only in self-defence or for the purpose of maintaining its security, territorial integrity and sovereignty.[16]

Public offices and related matters

The Constitution defines the role of the Attorney General. He is appointed by the King on the advice of the Prime Minister. The Attorney General functions as the legal aid and representative of the government and has the right to appear before any court. The Attorney General has the authority to appear before Parliament to express legal opinions and to institute, initiate, or withdraw any case. The Attorney General functions in accordance with the Attorney General Act.[19]

The Constitution provides for a Pay Commission. The Pay Commission operates independently, but its actions must be approved by the Lhengye Zhungtshog. Its Chairperson is appointed by the King on the advice of the Prime Minister.[14][20]

The Constitution places requirements on holders of Constitutional Offices. Judicial appointees, the Auditor General, and the Chairs of Anti-Corruption, Civil Service, and Election Commissions are holders of Constitutional Office. Holders of these offices must be natural-born citizens of Bhutan and must not be married to non-citizens. After five-year terms, they are ineligible for re-appointment.[13]

Article 32 sets forth the law regarding impeachment of Government Officers.

Emergencies, referenda, and textual authority

Article 33 sets forth plans in the event of a national emergency.

Article 34 sets forth the guidelines for conducting a National Referendum.

Article 35 contains provisions regarding Constitutional Amendment and the authoritativeness of the Dzongkha version of the Constitution.

Schedules and glossary

The First Schedule contains the National Flag and the National Emblem of Bhutan, referenced in Article 1 § 5. The Second Schedule contains the National Anthem of Bhutan, referenced in Article 1 § 6. The Third Schedule contains the "Oath or Affirmation of Office." The Fourth Schedule contains the "Oath or Affirmation of Secrecy."

The last part of the English-language version of the Constitution of Bhutan is a glossary containing many terms translated herein.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Background". Government of Bhutan. Archived from the original on 2010-07-15. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ Newburger, Emily (Summer 2007). "New Dynamics in Constitutional Law". Harvard Law Bulletin. Harvard Law School. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- 1 2 3 "Royal Command". Government of Bhutan. Archived from the original on 2010-07-16. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ↑ "Meeting". Government of Bhutan. Archived from the original on 2010-07-18. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ "Consultation". Government of Bhutan. Archived from the original on 2010-07-15. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ↑ "Bhutan 2008". Constitute. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 21

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 23

- 1 2 3 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 25

- 1 2 3 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 26

- 1 2 3 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 27

- 1 2 3 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 31

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 3

- 1 2 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 28

- 1 2 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 13

- 1 2 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 24

- 1 2 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 29

- 1 2 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 30

- 1 2 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 4

- 1 2 3 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 5

- 1 2 3 4 5 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 7

- 1 2 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 9

- ↑ Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 14

- ↑ Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 10

- ↑ Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 11

- ↑ Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 12

- ↑ Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 18

- ↑ Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 19

- 1 2 3 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 20

- ↑ Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 17

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 22

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 15

- ↑ Constitution of Bhutan Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Art. 16

References

- "The Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan" (PDF). Government of Bhutan. 2008-07-18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

Further reading

- Klaus Hofmann (2006-01-04). "Democratization from above: The case of Bhutan" (PDF). Democracy International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- "Countries at the Crossroads 2007: Bhutan" (PDF). Freedom House. 2007. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- Marian Gallenkamp (March 2010). "Democracy in Bhutan: An Analysis of Constitutional Change in a Buddhist Monarchy" (PDF). IPCS. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

External links

- "༄༅།།འབྲུག་གི་རྩ་ཁྲིམས་ཆེན་མོ།།" [The Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan] (PDF) (in Dzongkha). Government of Bhutan. 2008-07-18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- Official Website of the Government of Bhutan