Contingent election

A contingent election is a procedure used in United States presidential elections in the case where no candidate wins an absolute majority of votes in the Electoral College. A contingent election for the president is decided by a vote of the United States House of Representatives, whereas a contingent election for the vice president is decided by a vote of the United States Senate.

Contingent elections are extremely rare, having occurred only three times in the history of the United States, all in the early nineteenth century. In 1800, Thomas Jefferson was pitted against his own vice-presidential nominee in a contingent election due to the oddities of the pre-Twelfth Amendment electoral procedure. In 1824, the presence of four candidates split the Electoral College, and Andrew Jackson lost the contingent election to John Quincy Adams despite winning a plurality of both the popular and electoral vote. In 1836, faithless electors in Virginia refused to vote for Martin Van Buren's vice-presidential nominee Richard Mentor Johnson, denying him a majority of the electoral vote and forcing the Senate to elect him in a contingent election.

Background

In the United States, the President and Vice President are elected by the Electoral College, which consists of 538 presidential electors from the fifty states and Washington, D.C.. Presidential electors are themselves elected on a state-by-state basis. Since the election of 1824,[1] most states have appointed their electors on a winner-take-all basis, based on the statewide popular vote on Election Day. Maine and Nebraska are the only two current exceptions, as both states use the congressional district method. Although ballots list the names of the presidential and vice presidential candidates (who run on a ticket), voters actually choose electors when they vote for president and vice president. These presidential electors in turn cast electoral votes for those two offices. Electors usually pledge to vote for their party's nominee, but some "faithless electors" have voted for other candidates.

A candidate must receive an absolute majority of electoral votes (currently 270) to win the presidency or the vice presidency. If no candidate receives a majority in the election for president or vice president, that election is determined via a contingency procedure established by the Twelfth Amendment. In such a situation, the House chooses one of the top three presidential electoral vote-winners as the president, while the Senate chooses one of the top two vice presidential electoral vote-winners as vice president.

Section 3 of the Twentieth Amendment specifies that if the House of Representatives has not chosen a president-elect in time for the inauguration (noon on January 20), then the vice president-elect becomes acting president until the House selects a president. Section 3 also specifies that Congress may statutorily provide for who will be acting president if there is neither a president-elect nor a vice president-elect in time for the inauguration. Under the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, the Speaker of the House would become acting president until either the House selects a president or the Senate selects a vice president. None of these situations has ever occurred.

Procedure

Contingent presidential election by House

Pursuant to the Twelfth Amendment, the House of Representatives is required to go into session immediately after the counting of the electoral votes to vote for president if no candidate for president receives a majority of the electoral votes (currently 270 of the 538 electoral votes). In this event, the House of Representatives is limited to choosing from among the three candidates who received the most electoral votes. Each state delegation votes en bloc, with each state having a single vote. The District of Columbia does not receive a vote. A candidate must receive an absolute majority of state delegation votes (currently 26 votes) in order for that candidate to become the President-elect. The House continues balloting until it elects a president.

The House of Representatives has chosen the president only twice: in 1801 under Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 and in 1825 under the Twelfth Amendment.

Contingent vice presidential election by Senate

If no candidate for vice president receives an absolute majority of electoral votes, then the Senate must go into session to elect a vice president. The Senate is limited to choosing from only the two candidates who received the most electoral votes. The Senate votes in the normal manner, casting ballots individually and not by state delegations. Additionally, the Twelfth Amendment states that a "majority of the whole number" of senators (currently 51 of 100) is necessary for election.[2] The language requiring an absolute majority of Senate votes may preclude the sitting vice president from breaking any tie which might occur,[3] although some academics and journalists have speculated to the contrary.[4]

The only time the Senate chose the vice president was in 1837.[5]

Past contingent elections

Presidential election of 1800

The 1800 presidential election pitted Democratic-Republican ticket Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr against Federalist Party ticket John Adams and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Under the United States Constitution as it then stood, before the passage of the Twelfth Amendment each elector cast two votes, and the candidate with a majority of the votes was elected president, with the vice-presidency going to the runner-up. The Democratic-Republicans had a plan to have one of their electors cast a vote for another candidate instead of Burr, but failed to execute it, thus Jefferson and Burr tied at 73 electoral votes each.

Although the congressional election of 1800 turned over majority control of the House of Representatives to the Democratic-Republicans by 68 seats to 38,[6] the presidential election had to be decided by the outgoing House that had been elected in the congressional election of 1798, in which the Federalists retained a majority of 60 seats to 46.[6][7]

While it was common knowledge that Jefferson was the candidate for president and Burr for vice-president, many Federalists were unwilling to support Jefferson, their principal political opponent since 1789, and most Federalists voted for Burr. Over the course of seven days, from February 11 to 17, the House cast a total of 35 ballots, with Jefferson receiving the votes of eight state delegations each time, one short of the necessary majority of nine. On February 17, on the 36th ballot, Jefferson was elected. Several Federalist representatives cast blank ballots, resulting in in Maryland and Vermont's votes changing from no selection to Jefferson, giving him the votes of 10 states and the presidency.[8] This situation was the impetus for the passage of the Twelfth Amendment, which provided for separate elections for president and vice president in the Electoral College.

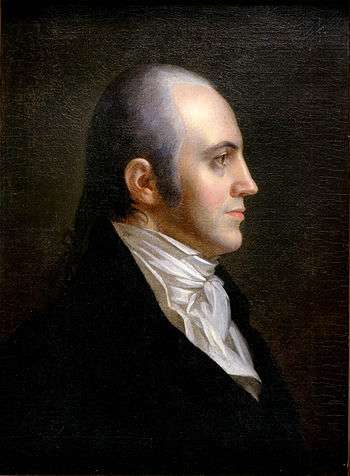

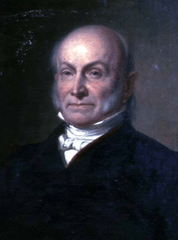

Presidential election of 1824

The 1824 presidential election came at the end of the Era of Good Feelings in American politics, and featured four candidates who would win electoral votes: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, William H. Crawford, and Henry Clay. Andrew Jackson received more electoral and popular votes than any other candidate, but not the majority of 131 electoral votes needed to win the election, leading to a contingent election in the House of Representatives. (Vice presidental candidate John C. Calhoun easily defeated his rivals, as the support of both the Adams and Jackson camps gave him an unassailable lead over the other candidates.)

Following the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment, only the top three candidates in the electoral vote were admitted as candidates in the House: Jackson, Adams, and Crawford. Clay, who happened to be Speaker of the House at the time, was left out. Clay threw his support to Adams, who was elected President on February 9, 1825, on the first ballot,[9][10] with 13 states, followed by Jackson with 7, and Crawford with 4.

Adams' victory shocked Jackson, who, as the winner of a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes, expected to be elected president. By appointing Clay his Secretary of State, President Adams essentially declared him heir to the Presidency, as Adams and his three predecessors had all served as Secretary of State. Jackson and his followers accused Adams and Clay of striking a "corrupt bargain". The Jacksonians would campaign on this claim for the next four years, ultimately attaining Jackson's victory in the Adams-Jackson rematch in 1828.

Vice presidential election of 1836

In the 1836 presidential election, Democratic presidential candidate Martin Van Buren and his running mate Richard Mentor Johnson won the popular vote in enough states to receive a majority of the Electoral College. However, Virginia's 23 electors all became faithless electors and refused to vote for Johnson, leaving him one vote short of the 148-vote majority required to elect him. Under the Twelfth Amendment, a contingent election in the Senate had to decide between Johnson and Whig candidate Francis Granger. Johnson was elected easily in a single ballot by 33 to 16.[11]

References

- ↑ McCarthy, Devin. "How the Electoral College Became Winner-Take-All". Fairvote. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ↑ "RL30804: The Electoral College: An Overview and Analysis of Reform Proposals, L. Paige Whitaker and Thomas H. Neale, January 16, 2001". Ncseonline.org. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ↑ Longley, Lawrence D.; Pierce, Neal R. (1999). "The Electoral College Primer 2000". New Haven, CT: Yale University Press: 13.

- ↑ "Election evolves into 'perfect' electoral storm". USA Today. December 12, 2000. Archived from the original on May 15, 2006. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Senate Journal from 1837". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- 1 2 "Party Divisions of the House of Representatives* 1789–Present". Office of the Historian, House of United States House of Representatives. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ↑ Ferling (2004)

- ↑ Ferling (2004)

- ↑ Adams, John Quincy; Adams, Charles Francis (1874). Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848. J.B. Lippincott & Co. pp. 501–505. ISBN 0-8369-5021-6. Retrieved August 2, 2006 – via Google Books.

- ↑ United States Congress (1825). House Journal. 18th Congress, 2nd Session, February 9. pp. 219–222. Retrieved August 2, 2006.

- ↑ http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsj&fileName=026/llsj026.db&recNum=227&itemLink=r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(sj02650)):%230260228&linkText=1