United States presidential election, 1824

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

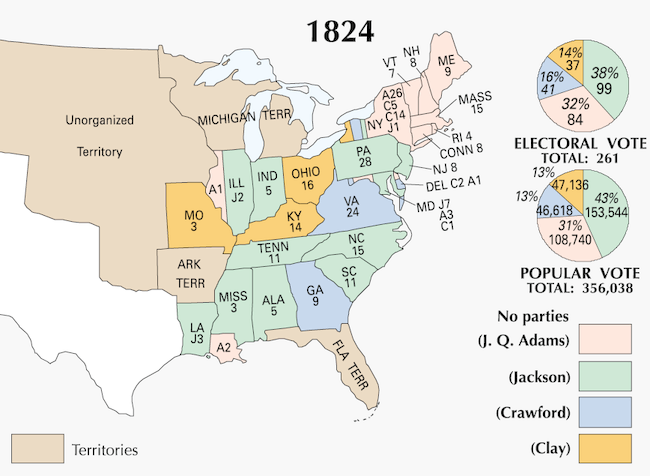

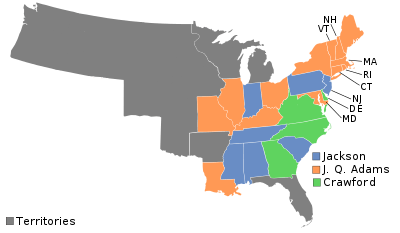

| Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Jackson, orange denotes those won by Crawford, green denotes those won by Adams, light yellow denotes those won by Clay. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States presidential election of 1824 was the tenth quadrennial presidential election, held from Tuesday, October 26, to Thursday, December 2, 1824. John Quincy Adams was elected President on February 9, 1825. The election was the only one in history to be decided by the House of Representatives under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution after no candidate secured a majority of the electoral vote. It was also the only presidential election in which the candidate who received a plurality of electoral votes (Andrew Jackson) did not become President, a source of great bitterness for Jackson and his supporters, who proclaimed the election of Adams a corrupt bargain.

Prior to the election, the Democratic-Republican Party had won six consecutive presidential elections. In 1824 the Democratic-Republican Party failed to agree on a choice of candidate for president, with the result that the party effectively ceased to exist and split four ways behind four separate candidates. Later, the faction led by Jackson would evolve into the modern Democratic Party in the 1828 election, while the factions led by Adams and Henry Clay would become the National Republican Party (not related to the current Republican Party) and then the Whig Party.

Background

The Era of Good Feelings, closely associated with the administration of President James Monroe (1817-1825), was characterized by the dissolution of national political identities.[1] With the discredited Federalists in decline nationally, the “amalgamated” or hybridized Republicans adopted key Federalist economic programs and institutions, further erasing party identities and consolidating their victory.[2][3] The economic nationalism of the Era of Good Feelings that would authorize the Tariff of 1816 and incorporate the Second Bank of the United States portended an abandonment of the Jeffersonian political formula for strict construction of the constitution, limited central government and commitments to the primacy of Southern agrarian interests.[4][5][6]

The end of opposition parties also meant the end of party discipline and the means to suppress internecine factional animosities. Rather than produce political harmony, as President James Monroe had hoped, amalgamation had led to intense rivalries among Republicans.[7]Bereft of any party apparatus to contain these outbursts, Monroe attempted to enlist the leading statesmen of his day into his cabinet so as to commit them to advancing his policies. Of the five politicians who would run for president in in 1824, three were in Monroe’s cabinet: Secretary of State John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford of Georgia, and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. General Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, a commander in the regular US Army, was tapped for high profile military assignments. Only Speaker of the House of Representatives Henry Clay of Kentucky held political power independent of the Monroe administration. Monroe’s efforts to bring Clay into his cabinet failed, and the Speaker remained a persistent critic of the Monroe administration.

Amid these reconfigured political landscapes arose two pivotal events: the Panic of 1819 and the Missouri crisis of 1820.[8] Both the alarming economic disaster, which fell heavily upon both agrarian and industrial workers, and the distressing sectional disputes over slavery expansion, produced widespread social unrest and calls for increased democratic control over the future of the American republic.[9] From these disaffected social groups would be assembled the popular base on which political parties would be revived in the 1820s, and only beginning to take shape at the time of the 1824 presidential election.[10]

General election

Campaign

The previous competition between the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party collapsed after the War of 1812 due to the disintegration of the Federalists' popular appeal, and U.S. President James Monroe of the Democratic-Republican Party was able to run without opposition in the election of 1820. Like previous presidents who had been elected to two terms, James Monroe declined to seek re-nomination for a third term.[11]

Monroe's vice president, Daniel D. Tompkins, was considered unelectable due to his overwhelming unpopularity and major health problems (Tompkins died in June 1825, a little over three months after he left office). The presidential nomination was thus left wide open within the Democratic-Republican Party, the only major national political entity remaining in the United States.

Candidates

-

Senator Andrew Jackson from Tennessee

Candidates who withdrew before election

Nomination process

| Presidential Ballot | Vice Presidential Ballot | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| William H. Crawford | 64 | Albert Gallatin | 57 |

| Henry Clay | 2 | ||

| John Quincy Adams | 2 | Erastus Root | 2 |

| Andrew Jackson | 1 | John Quincy Adams | 1 |

| William Eustis | 1 | ||

| William Rufus King | 1 | ||

| William Lowndes | 1 | ||

| Richard Rush | 1 | ||

| Samuel Smith | 1 | ||

| John Tod | 1 |

The traditional Congressional caucus nominated Crawford for president and Albert Gallatin for vice-president, but it was sparsely attended and was widely attacked as undemocratic. Gallatin later withdrew from the contest for the vice presidency, after quickly becoming disillusioned by repeated attacks on his credibility made by the other candidates. He was replaced by North Carolina senator Nathaniel Macon. A serious impediment to Crawford's candidacy was created by the effects of a stroke he suffered in 1823. Among other candidates, John Quincy Adams had more support than Henry Clay because of his huge popularity among the old Federalist voters in New England. By this time, even the traditionally Federalist Adams family had come to terms with the Democratic-Republican Party.

The election was as much a contest of favorite sons as it was a conflict over policy, although positions on tariffs and internal improvements did create some significant disagreements. In general, the candidates were favored by different sections of the country: Adams was strong in the Northeast; Jackson in the South, West and mid-Atlantic; Clay in parts of the West; and Crawford in parts of the East.

Secretary of War John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who was a fifth candidate in the early stages of consideration, declined to run for president, but did decide to seek the vice presidency. For president, he backed Jackson, whose political beliefs he considered more compatible with those of most voters in the southern states. Both Adams and Jackson supporters backed Calhoun's candidacy as vice president; thus, he easily secured the majority of electoral votes he needed to secure that office. In reality, Calhoun was vehemently opposed to nearly all of Adams's policies, but he did nothing to dissuade Adams supporters from voting for him for vice president.

The campaigning for presidential election of 1824 took many forms. Contrafacta, or well known songs and tunes whose lyrics have been altered, were used to promote political agendas and presidential candidates. Below can be found a sound clip featuring "Hunters of Kentucky," a tune written by Samuel Woodsworth in 1815 under the title "The Unfortunate Miss Bailey." Contrafacta such as this one, which promoted Andrew Jackson as a national hero, have been a long-standing tradition in presidential elections. Another form of campaigning during this election was through newsprint. Political cartoons and partisan writings were best circulated among the voting public through newspapers. Presidential candidate John C. Calhoun was one of the candidates most directly involved through his participation in the publishing of the newspaper The Patriot as a member of the editorial staff. This was a sure way to promote his own political agendas and campaign. In contrast, most candidates involved in early 19th century elections did not run their own political campaigns. Instead it was left to volunteer citizens and partisans to speak on their behalf.[12][13][14][15]

|

Hunters of Kentucky

Jackson supporters used this Battle of New Orleans anthem as their campaign song. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Results

Considering the large numbers of candidates and strong regional preferences, it is not surprising that the results of the election of 1824 were inconclusive. The electoral map confirmed the candidates' sectional support, with Adams winning outright in the New England states, Jackson gleaning success in states throughout the nation, Clay attracting votes from the West, and Crawford attracting votes from the eastern South. Andrew Jackson received more electoral and popular votes than any other candidate, but not the majority of 131 electoral votes needed to win the election. Since no candidate received the required majority of electoral votes, the presidential election was decided by the House of Representatives (see "Contingent election" below). Meanwhile, John C. Calhoun easily defeated his rivals in the race for the vice presidency, as the support of both the Adams and Jackson camps quickly gave him an unassailable lead over the other candidates.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote[lower-alpha 1] | Electoral vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| Andrew Jackson[lower-alpha 2] | Democratic-Republican | Tennessee | 151,271 | 41.4% | 99 |

| John Quincy Adams[lower-alpha 3] | Democratic-Republican | Massachusetts | 113,122 | 30.9% | 84 |

| William Harris Crawford[lower-alpha 4] | Democratic-Republican | Georgia | 40,856 | 11.2% | 41 |

| Henry Clay[lower-alpha 5] | Democratic-Republican | Kentucky | 47,531 | 13.0% | 37 |

| (Massachusetts unpledged electors) | None | Massachusetts | 6,616 | 1.8% | 0 |

| Other | 6,437 | 1.8% | 0 | ||

| Total | 365,833 | 100.0% | 261 | ||

| Needed to win | 131 | ||||

| Vice Presidential candidate | Party | State | Electoral vote[17] |

|---|---|---|---|

| John C. Calhoun | Democratic-Republican | South Carolina | 182 |

| Nathan Sanford | Democratic-Republican | New York | 30 |

| Nathaniel Macon | Democratic-Republican | North Carolina | 24 |

| Andrew Jackson | Democratic-Republican | Tennessee | 13 |

| Martin Van Buren | Democratic-Republican | New York | 9 |

| Henry Clay | Democratic-Republican | Kentucky | 2 |

| Total | 260 | ||

| Needed to win | 131 | ||

Results by state

| Andrew Jackson Democratic-Republican |

John Quincy Adams Democratic-Republican |

Henry Clay Democratic-Republican |

William Crawford Democratic-Republican |

State Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | ||

| Alabama | 5 | 9,429 | 69.32 | 5 | 2,422 | 17.80 | - | 96 | 0.71 | - | 1,656 | 12.17 | - | 13,603 | AL | |

| Connecticut | 8 | no ballots | 7,494 | 70.39 | 8 | no ballots | 1,965 | 18.46 | - | 10,647 | CT | |||||

| Delaware | 3 | no popular vote | no popular vote | 1 | no popular vote | no popular vote | 2 | - | DE | |||||||

| Georgia | 9 | no popular vote | no popular vote | no popular vote | no popular vote | 9 | - | GA | ||||||||

| Illinois | 3 | 1,272 | 27.23 | 2 | 1,516 | 32.46 | 1 | 1,036 | 22.18 | - | 847 | 18.13 | - | 4,671 | IL | |

| Indiana | 5 | 7,343 | 46.61 | 5 | 3,095 | 19.65 | - | 5,315 | 33.74 | - | no ballots | 15,753 | IN | |||

| Kentucky | 14 | 6,356 | 27.23 | - | no ballots | 16,982 | 72.77 | 14 | no ballots | 23,338 | KY | |||||

| Louisiana | 5 | no popular vote | 3 | no popular vote | 2 | no popular vote | no popular vote | - | LA | |||||||

| Maine | 9 | no ballots | 10,289 | 81.50 | 9 | no ballots | 2,336 | 18.50 | - | 12,625 | ME | |||||

| Maryland | 11 | 14,523 | 43.73 | 7 | 14,632 | 44.05 | 3 | 695 | 2.09 | - | 3,364 | 10.13 | 1 | 33,214 | MD | |

| Massachusetts | 15 | no ballots | 30,687 | 72.97 | 15 | no ballots | no ballots | 42,056 | MA | |||||||

| Mississippi | 3 | 3,121 | 63.77 | 3 | 1,654 | 33.80 | - | no ballots | 119 | 2.43 | - | 4,894 | MS | |||

| Missouri | 3 | 1,166 | 33.97 | - | 159 | 4.63 | - | 2,042 | 59.50 | 3 | 32 | 0.93 | - | 3,432 | MO | |

| New Hampshire | 8 | no ballots | 9,389 | 93.59 | 8 | no ballots | 643 | 6.41 | - | 10,032 | NH | |||||

| New Jersey | 8 | 10,332 | 52.08 | 8 | 8,309 | 41.89 | - | no ballots | 1,196 | 6.03 | - | 19,837 | NJ | |||

| New York | 36 | no popular vote | 1 | no popular vote | 26 | no popular vote | 4 | no popular vote | 5 | - | NY | |||||

| North Carolina | 15 | 20,231 | 56.03 | 15 | no ballots | no ballots | 15,622 | 43.26 | - | 36,109 | NC | |||||

| Ohio | 16 | 18,489 | 36.96 | - | 12,280 | 24.55 | - | 19,255 | 38.49 | 16 | no ballots | 50,024 | OH | |||

| Pennsylvania | 28 | 35,929 | 76.04 | 28 | 5,436 | 11.50 | - | 1,705 | 3.61 | - | 4,182 | 8.85 | - | 47,252 | PA | |

| Rhode Island | 4 | no ballots | 2,145 | 91.47 | 4 | no ballots | 200 | 8.53 | - | 2,345 | RI | |||||

| South Carolina | 11 | no popular vote | 11 | no popular vote | no popular vote | no popular vote | - | SC | ||||||||

| Tennessee | 11 | 20,197 | 97.45 | 11 | 216 | 1.04 | - | no ballots | 312 | 1.51 | - | 20,725 | TN | |||

| Vermont | 7 | no popular vote | no popular vote | 7 | no popular vote | no popular vote | 35,031 | VT | ||||||||

| Virginia | 24 | 2,975 | 19.35 | - | 3,419 | 22.24 | - | 419 | 2.73 | - | 8,558 | 55.68 | 24 | 15,371 | VA | |

| TOTALS: | 261 | 151,363 | 41.36 | 99 | 113,142 | 30.92 | 84 | 47,545 | 12.99 | 37 | 41,032 | 11.21 | 41 | 365,928 | US | |

| TO WIN: | 131 | |||||||||||||||

Breakdown by ticket

| Total | Andrew Jackson | John Q. Adams | William H. Crawford | Henry Clay | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electoral Votes for President: | 261 | 99 | 84 | 40 | 38 |

| For Vice President, John C. Calhoun | 182 | 99 | 74 | 2 | 7 |

| For Vice President, Nathan Sanford | 30 | 2 | 28 | ||

| For Vice President, Nathaniel Macon | 24 | 24 | |||

| For Vice President, Andrew Jackson | 13 | 9 | 1 | 3 | |

| For Vice President, Martin Van Buren | 9 | 9 | |||

| For Vice President, Henry Clay | 2 | 2 | |||

| (No vote for Vice President) | 1 | 1 |

1825 Contingent election

Since no candidate received a majority of the electoral votes, the presidential election was thrown into a contingent election in the U.S. House of Representatives. Following the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment, only the top three candidates in the electoral vote were admitted as candidates in the House: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and William Harris Crawford. Henry Clay, who happened to be Speaker of the House at the time, was left out. Clay detested Jackson and had said of him, "I cannot believe that killing 2,500 Englishmen at New Orleans qualifies for the various, difficult, and complicated duties of the Chief Magistracy."[18] Moreover, Clay's American System was far closer to Adams' position on tariffs and internal improvements than Jackson's or Crawford's, so Clay threw his support to Adams. Thus Adams was elected President on February 9, 1825, on the first ballot,[19][20] with 13 states, followed by Jackson with 7, and Crawford with 4.

Adams' victory shocked Jackson, who, as the winner of a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes, expected to be elected president. Interestingly enough, not too long before the results of the House election, an anonymous statement appeared in a Philadelphia paper, called the Columbian Observer. The statement, said to be from a member of Congress, essentially accused Clay of selling Adams his support for the office of Secretary of State. No formal investigation was conducted, so the matter was neither confirmed nor denied. When Clay was indeed offered the position after Adams was victorious, he opted to accept and continue to support the administration he voted for, knowing that declining the position would not have helped to dispel the rumors brought against him.[21] By appointing Clay his Secretary of State, President Adams essentially declared him heir to the Presidency, as Adams and his three predecessors had all served as Secretary of State. Jackson and his followers accused Adams and Clay of striking a "corrupt bargain". The Jacksonians would campaign on this claim for the next four years, ultimately attaining Jackson's victory in the Adams-Jackson rematch in 1828.

Results by state in House of Representatives

| Delegation winner | Adams vote | Jackson vote | Crawford vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maine | Adams | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| New Hampshire | Adams | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Vermont | Adams | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Massachusetts | Adams | 12 | 1 | 0 |

| Rhode Island | Adams | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Connecticut | Adams | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| New York | Adams | 18 | 2 | 14 |

| New Jersey | Jackson | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | Jackson | 1 | 25 | 0 |

| Delaware | Crawford | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Maryland | Adams | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| Virginia | Crawford | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| North Carolina | Crawford | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| South Carolina | Jackson | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Georgia | Crawford | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Alabama | Jackson | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Mississippi | Jackson | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Louisiana | Adams | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Kentucky | Adams | 8 | 4 | 0 |

| Tennessee | Jackson | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Missouri | Adams | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ohio | Adams | 10 | 2 | 2 |

| Indiana | Jackson | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Illinois | Adams | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total votes[22] | Adams | 87 (41%) | 71 (33%) | 54 (25%) |

| Votes by state | Adams | 13 (54%) | 7 (29%) | 4 (17%) |

Electoral College selection

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| Each Elector chosen by voters statewide | Alabama Connecticut Indiana Massachusetts Mississippi New Hampshire New Jersey North Carolina Ohio Pennsylvania Rhode Island Virginia |

| Each Elector appointed by state legislature | Delaware Georgia Louisiana New York South Carolina Vermont |

| State is divided into electoral districts, with one Elector chosen per district by the voters of that district | Illinois Kentucky Maryland Missouri Tennessee |

|

Maine |

See also

- Corrupt Bargain

- Electoral college

- History of the United States (1789-1849)

- Inauguration of John Quincy Adams

- Realigning election

- Second Party System

- Smoke-filled room

- United States House elections, 1824

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 The popular vote figures exclude Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, New York, South Carolina, and Vermont. In all of these states, the Electors were chosen by the state legislatures rather than by popular vote.[16]

- ↑ Jackson was nominated by the Tennessee state legislature and by the Democratic Party of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Adams was nominated by the Massachusetts state legislature.

- ↑ Crawford was nominated by a caucus of 66 congressmen that called itself the "Democratic members of Congress".

- ↑ Clay was nominated by the Kentucky state legislature.

References

- ↑ Ammon, 1958, p. 4: “The phrase ‘Era of Good Feelings’, so inextricably associated with the administration of James Monroe…”

- ↑ Ammon, 1958, p. 5: “Most Republicans like former President [James] Madison readily acknowledged the shift that had taken place within the Republican party towards Federalist principles and viewed the process without qualms. And p. 4: “…The Republicans had taken over (as they saw it) that which was of permanent value in the Federal program.” And p. 10: “…Federalists had vanished” from national politics.

- ↑ Brown, 1966, p. 23: “…a new theory of party amalgamation preached the doctrine that party division was bad and that a one-party system best served the national interest” and “After 1815, stirred by the nationalism of the post-war era, and with the Federalists in decline, the Republicans took up the Federalist positions on a number of the great public issues of the day, sweeping all before them as they did. The Federalists gave up the ghost.”

- ↑ Brown, 1966, p. 23: The amalgamated Republicans, “as a party of the whole nation…ceased to be responsive to any particular elements in its constituency. It ceased to be responsive to the South.” And “The insistence that slavery was uniquely a Southern concern, not to be touched by outsiders, had been from the outset a sine qua non for Southern participation in national politics. It underlay the Constitution and its creation of a government of limited powers…”

- ↑ Brown, 1966, p. 24: “Not only did the Missouri crisis make these matters clear [the need to revive strict constructionist principles and quiet anti-slavery agitation], but “it gave marked impetus to a reaction against nationalism and amalgamation of postwar Republicanism” and the rise of the Old Republicans.

- ↑ Ammon, 1971 (James Monroe bio) p. 463: “The problems presented by the [consequences of promoting Federalist economic nationalism] gave an opportunity to the older, more conservative [Old] Republicans to reassert themselves by attributing the economic dislocation to a departure from the principles of the Jeffersonian era.”

- ↑ Parsons, 2009, p. 56: “Animosity between Federalists and Republicans had been replaced by animosity between Republicans themselves, often over the same issues that had once separated them from the Federalists.”

- ↑ Wilentz, 2008, p. 251-252: “The panic …was pivotal…the hard times of 1819 and early 1820s revive[d]…fundamental questions about the nationalist economic policies of the new-style Republicans under Madison and Monroe, and focused inchoate popular resentments on the banks, especially the Second BUS.” P. 252: “The Missouri controversy…proved for more important than the [incidental] outbursts.”

- ↑ Wilentz, 2008, p. 252: “Both the panic and the Missouri debates underscored in different ways the overriding question of democracy as Americans perceived it. In economic matters, the questions arose primarily as a matter of privilege. Should unelected private interests, well connected to government, be permitted to control, to their own benefit, the economic destiny of the entire nation?”

- ↑ Hofstadter, 1947, p. 51: The “general mass of the disaffection to the Government was not sufficiently concentrated to prevent re-election, unopposed, of President Monroe in 1820 in the absence of a national opposition party; but it soon transformed politics in many states. Debtors rushed into politics to defend themselves, and secured moratoriums and relief laws from the legislatures of several Western states… A popular demand arose for laws to prevent imprisonment for debt, for a national bankruptcy law, and for a new tariff and public land policies. For the first time Americans thought of politics as having an intimate relation to their welfare.”

- ↑ Ratcliffe, Donald (2015). The One-Party Presidential Contest: Adams, Jackson, and 1824's Five-Horse Race.

- ↑ Hansen, Liane (October 5, 2008). "Songs Along The Campaign Trail". Election 2008: On The Campaign Trail (Radio series episode). National Public Radio.

- ↑ Hay, Thomas R. (October 1934). "John C. Calhoun and the Presidential Campaign of 1824, Some Unpublished Calhoun Letters". The American Historical Review. 40 (1). JSTOR 1838676.

- ↑ McNamara, R. (September 2007). "The Election of 1824 Was Decided in the House of Representatives". About.com. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ↑ Schimler, Stuart (February 12, 2002). "Singing to the Oval Office: A Written History of the Political Campaign Song". President Elect Articles. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- ↑ Leip, David. "1824 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 26, 2005.

- ↑ "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005.

- ↑ Henry Clay to Francis Preston Blair, January 29, 1825.

- ↑ Adams, John Quincy; Adams, Charles Francis (1874). Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848. J.B. Lippincott & Co. pp. 501–505. ISBN 0-8369-5021-6. Retrieved August 2, 2006 – via Google Books.

- ↑ United States Congress (1825). House Journal. 18th Congress, 2nd Session, February 9. pp. 219–222. Retrieved August 2, 2006.

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur Meier; Israel, Fred L. (1971). History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–1968, Volume I, 1789–1844. New York: Chelsea House. pp. 379–381. ISBN 0070797862. Retrieved November 19, 2008 – via Google Books.

- ↑ McMaster, J. B. (1900). History of the People of the United States... vol. V. New York: D. Appleton and Company. p. 81. Reprinted in Bemis, Samuel Flagg (1965). John Quincy Adams and the Union. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 54.

- ↑ Akin (1824). "Caucus curs in full yell, or a war whoop, to saddle on the people, a pappoose president / J[ames] Akin, Aquafortis". Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

Citations

- Ammons, Harry. 1959. "James Monroe and the Era of Good Feelings." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, LXVI, No. 4 (October 1958), pp. 387–398, in Essays on Jacksonian America, Ed. Frank Otto Gatell. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

- Brown, Richard H. 1966. "The Missouri Crisis, Slavery, and the Politics of Jacksonianism." South Atlantic Quarterly, pp. 55–72, in Essays on Jacksonian America, Ed. Frank Otto Gatell. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

- Dangerfield, George. 1965. The Awakening of American Nationalism: 1815-1828. New York: Harper & Row.

- Wilentz, Sean. 2008. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: Horton.

Further reading

- Brown, Everett S. (1925). "The Presidential Election of 1824–1825". Political Science Quarterly: 384–403. JSTOR 2142211.

- Kolodny, Robin (1996). "The Several Elections of 1824". Congress & the Presidency: A Journal of Capital Studies. 23 (2).

- Nagel, Paul C. (1960). "The Election of 1824: A Reconsideration Based on Newspaper Opinion". Journal of Southern History: 315–329. JSTOR 2204522.

- Ratcliffe, Donald J. The One-Party Presidential Contest: Adams, Jackson, and 1824's Five-Horse Race ((University Press of Kansas, 2015. xiv, 354 pp.

External links

- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved March 20, 2005.

- Presidential Election of 1824: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Election of 1824 in Counting the Votes

- Murphy, Sharon Ann. A Not-So-Corrupt Bargain Review of The One-Party Presidential Contest: Adams, Jackson and and 1824’s Five-Horse Race by Donald Ratcliffe. Common-place.org. Vol. 16, No. 4