Henry Clay

| Henry Clay | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Kentucky | |

|

In office March 4, 1849 – June 29, 1852 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Metcalfe |

| Succeeded by | David Meriwether |

|

In office November 10, 1831 – March 31, 1842 | |

| Preceded by | John Rowan |

| Succeeded by | John J. Crittenden |

|

In office January 4, 1810 – March 4, 1811 | |

| Preceded by | Buckner Thruston |

| Succeeded by | George M. Bibb |

|

In office December 29, 1806 – March 4, 1807 | |

| Preceded by | John Adair |

| Succeeded by | John Pope |

| 9th United States Secretary of State | |

|

In office March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1829 | |

| President | John Quincy Adams |

| Preceded by | John Quincy Adams |

| Succeeded by | Martin Van Buren |

| 7th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

|

In office March 4, 1823 – March 4, 1825 | |

| Preceded by | Philip P. Barbour |

| Succeeded by | John W. Taylor |

|

In office March 4, 1815 – October 28, 1820 | |

| Preceded by | Langdon Cheves |

| Succeeded by | John W. Taylor |

|

In office March 4, 1811 – January 19, 1814 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph B. Varnum |

| Succeeded by | Langdon Cheves |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 3rd district | |

|

In office March 4, 1823 – March 4, 1825 | |

| Preceded by | John T. Johnson |

| Succeeded by | James Clark |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 2nd district | |

|

In office March 4, 1815 – March 3, 1821 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph H. Hawkins |

| Succeeded by | Samuel H. Woodson |

|

In office March 4, 1813 – January 19, 1814 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel McKee |

| Succeeded by | Joseph H. Hawkins |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 5th district | |

|

In office March 4, 1811 – March 3, 1813 | |

| Preceded by | William T. Barry |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Hopkins |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

April 12, 1777 Hanover County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died |

June 29, 1852 (aged 75) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party |

Democratic-Republican (1803–1825) National Republican (1825–1833) Whig (1833–1852) |

| Spouse(s) | Lucretia Hart (m. 1799–1852) |

| Children | 11, including Thomas, Henry, James, John |

| Alma mater | College of William and Mary |

| Religion | Episcopalianism |

| Signature |

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

Henry Clay, Sr. (April 12, 1777 – June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and planter, statesman, and skilled orator who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate and House of Representatives. He served three non-consecutive terms as Speaker of the House of Representatives and served as Secretary of State under President John Quincy Adams from 1825 to 1829. Clay ran for the presidency in 1824, 1832 and 1844, while also seeking his party's nomination in 1840 and 1848. However, he was unsuccessful in all of his attempts to reach his nation's highest office. Despite his presidential losses, Clay remained a dominant figure in the Whig Party, which he helped found in the 1830s.

Clay was a dominant figure in both the First and Second Party systems. After serving two brief stints in the Senate, Clay won election to the House of Representatives in 1810 and was elected Speaker of the House in 1811. Clay would remain a prominent public figure until his death 41 years later in 1852. A leading war hawk, Speaker Clay favored war with Britain and played a significant role in leading the nation into the War of 1812.[1] In 1814, Clay's tenure as Speaker was interrupted when Clay traveled to Europe, where he helped to negotiate the Treaty of Ghent with the British. After the war, Clay developed his American System, which called for an increase in tariffs to foster industry in the United States, the use of federal funding to build and maintain infrastructure, and a strong national bank. Clay ran for president in 1824 and lost, finishing fourth in a four-man contest. No candidate received an electoral majority, and so the election was decided in the House of Representatives. Clay maneuvered House voting in favor of John Quincy Adams, who appointed him as Secretary of State. Opposing candidate Andrew Jackson denounced the actions of Clay and Adams as part of a "corrupt bargain", and defeated Adams in the 1828 election, ending Clay's term as Secretary of State.

Clay returned to the Senate in 1831. He continued to advocate his American System, and become a leader of the opposition to President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party. President Jackson opposed federally-subsidized internal improvements and a national bank as a threat to states' rights, and the president used his veto power to defeat many of Clay's proposals. In 1832, Clay ran for president as a candidate of the National Republican Party, losing to Jackson. Following the election, the National Republicans united with other opponents of Jackson to form the Whig Party, which remained one of the two major American political parties until after Clay's death. In 1844, Clay won the Whig Party's presidential nomination. Clay's opposition to the annexation of Texas, partly over fears that such an annexation would inflame the slavery issue, hurt his campaign, and Democrat James K. Polk won the election. Clay later opposed the Mexican–American War, which resulted in part from the Texas annexation. Clay returned to the Senate for a final term, where he helped broker a compromise over the status of slavery in the Mexican Cession.

Known as "The Great Compromiser", Clay brokered important agreements during the Nullification Crisis and on the slavery issue. As part of the "Great Triumvirate" or "Immortal Trio," along with his colleagues Daniel Webster and John C. Calhoun, he was instrumental in formulating the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the Compromise Tariff of 1833, and the Compromise of 1850 to ease sectional tensions. He was viewed as the primary representative of Western interests in this group, and was given the names "Henry of the West" and "The Western Star."[2] As a plantation owner, Clay held slaves during his lifetime, but freed them in his will.[3]

Early life and education

Childhood

Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, at the Clay homestead in Hanover County, Virginia, in a story-and-a-half frame house. It was an above-average home for a "common" Virginia planter of that time. At the time of his death, Clay's father owned more than 22 slaves, making him part of the planter class in Virginia (those men who owned 20 or more slaves).[4] Henry Clay was of entirely English descent [5] whose Clay ancestors had been in Virginia since approximately 1612, when John Clay, born six generations before Clay, came to Virginia from England.[6]

Henry was the seventh of nine children of the Reverend John Clay and Elizabeth (née Hudson) Clay.[7] His father, a Baptist minister nicknamed "Sir John," died four years after the boy's birth (1781).[4] The father left Henry and his brothers two slaves each, and his wife 18 slaves and 464 acres (188 ha) of land.[8] Henry Clay was a second cousin of Cassius Marcellus Clay, who became a politician and an abolitionist in Kentucky.

Shortly after the death of Clay's father, the British under Banastre Tarleton raided Clay's home, leaving the family in a precarious position.[9] However, the widow Elizabeth Clay married Capt. Henry Watkins, who was an affectionate stepfather and a successful planter.[10] Elizabeth would have seven more children with Watkins, bearing a total of sixteen.[8] After his mother's remarriage, the young Clay remained in Hanover County, and learned how to read and write from an Englishman named Peter Deacon.[10] In 1791, Henry Watkins moved the family to Kentucky, joining his brother in the pursuit of fertile new lands in the West.[11] However, Clay did not follow, as Watkins secured his son temporary employment in a Richmond emporium, with the promise that Clay would receive the next available clerkship at the Virginia Court of Chancery.[11]

Education

After working in the emporium for one year, a clerkship finally opened up at the Virginia Court of Chancery. Clay adapted well to his new role, and his handwriting earned him the attention of George Wythe, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, mentor of Thomas Jefferson, and a judge on Virginia's High Court of Chancery.[12] Hampered by a crippled hand, Wythe chose Clay as his secretary and amanuensis, a role in which Clay would remain for four years.[13] The chancellor took an active interest in Clay's future, lending books and discussing philosophy with his young employee.[12] Wythe would have a powerful effect on Clay's worldview, and Clay embraced Wythe's view that the example of the United States could help spread human freedom around the world.[14] Clay also adopted Wythe's negative views on slavery (Wythe freed all of his slaves and hired some of them as free workers), though Clay continued to own slaves throughout his life.[14] Wythe arranged for Clay a position with the Virginia attorney general, Robert Brooke, with the understanding that Brooke would finish Clay's legal studies.[15] Clay was admitted to the Virginia Bar to practice law in 1797.[16] However, the Virginia legal field was competitive, with much depending on family ties, so Clay decided to move West to be closer to his family in Kentucky.[17]

Marriage and family

After beginning his law career, on April 11, 1799, Clay married Lucretia Hart at the Hart home in Lexington, Kentucky. One of her brothers was Nathaniel G. S. Hart, who later served as a captain in the War of 1812 and was killed in the Massacre of the River Raisin.[18] Lucretia's father, Thomas Hart, was the namesake and grand-uncle of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton.

Clay and his wife had eleven children (six daughters and five sons): Henrietta (1800–1801), Theodore (1802–1870), Thomas (1803–1871), Susan (1805–1825), Anne (1807–1835), Lucretia (1809–1823), Henry, Jr. (1811–1847), Eliza (1813–1825), Laura (1815–1817), James Brown Clay (1817–1864), and John Morrison Clay (1821–1887).

Seven of Clay's children died before him. By 1835 all six daughters had died of varying causes, two when very young, two as children, and the last two as young women: from whooping cough, yellow fever, and complications of childbirth, respectively. Henry Clay, Jr. was killed during the Mexican–American War at the Battle of Buena Vista. Clay's oldest son, Theodore, spent the second half of his life confined to a psychiatric hospital.[19]

Lucretia Hart Clay survived her husband, dying in 1864 at the age of 83. She is interred with her husband in the vault of his monument at the Lexington Cemetery. Henry and Lucretia Clay were great-grandparents of the suffragette Madeline McDowell Breckinridge.[20]

Early law and political career

Legal career

In November 1797, Clay relocated to Lexington, Kentucky, near where his parents and siblings then resided in Versailles, Kentucky.[21] The Bluegrass Region, with Lexington at its center, had quickly grown in the preceding decades, and had only recently stopped being under the threat of Native American raids with the end of the Northwest Indian War.[21] Lexington was an established town that could boast the first university west of the Appalachian Mountains.[21] Having already passed the Virginia Bar, Clay quickly received a Kentucky license to practice law.[22] After apprenticing himself to Kentucky attorneys such as George Nicholas, John Breckinridge, and James Brown, Clay established his own law practice, frequently working on debt collection and land disputes.[22] Clay soon established a reputation for his legal skills and courtroom oratory.[23] In 1805, Clay was appointed to the faculty of Transylvania University, where Clay taught, among others, future Kentucky Governor Robert P. Letcher, and Robert Todd, the future father-in-law of Abraham Lincoln.[24]

One of Clay's clients was his father-in-law, Colonel Thomas Hart, an early settler of Kentucky and a prominent businessman.[18] Hart proved to be an important business connection for Clay, as he helped Clay gain new clients and grow in professional stature.[25] Clay's most notable client was Aaron Burr in 1806, after the US District Attorney Joseph Hamilton Daveiss indicted him for allegedly planning an expedition into Spanish Territory west of the Mississippi River. Clay and his law partner John Allen successfully defended Burr.[26] Some years later Thomas Jefferson convinced Clay that Daveiss had been right in his charges. Clay was so upset that many years later, when he met Burr again, Clay refused to shake his hand.[27] Clay's legal career would continue long after his election to Congress, and in the 1823 Supreme Court case, Green v. Biddle, Clay submitted the Supreme Court's first amicus curiae.[28]

In 1804, Clay purchased land outside of Lexington, with the dream of building a plantation called "Ashland," named for the surrounding forest of ash trees.[29] By 1812, Clay owned a productive 600-acre (240 ha) plantation, with numerous slaves to working the land.[3] He held 60 slaves at the peak of operations, and likely produced tobacco and hemp, the two chief commodity crops of the Bluegrass Region. Clay introduced the Hereford livestock breed to the United States.

Early political career

Clay's legal work earned him a reputation as a defender of the common man, and Clay began dabbling in politics.[30] Like most other Kentuckians, Clay became a member of the Democratic-Republican Party,[31] but, as Kentucky debated revising its constitution, Clay clashed with the state party leadership.[32] Using the pseudonym "Scaevola" (in reference to Gaius Mucius Scaevola), Clay advocated for direct elections for Kentucky elected officials and the gradual abolition of slavery in Kentucky.[30] The 1799 Kentucky Constitution included the direct election of public officials, but Clay's advocacy for gradual emancipation fell on deaf ears.[30]

In 1803, although not old enough to be elected, Clay was appointed a representative of Fayette County in the Kentucky General Assembly.[33] Clay's first legislative initiative was the partisan gerrymander of Kentucky's Electoral College districts, which ensured that all of Kentucky's presidential electors voted for Thomas Jefferson in the 1804 presidential election.[34] Clay clashed with legislators who sought to reduce the power of Clay's Bluegrass Region, and Clay unsuccessfully advocated moving the state capitol from Frankfort to Lexington.[35] Clay frequently opposed Felix Grundy, a populist firebrand who unsuccessfully sought to revoke the banking privileges of the state-owned Kentucky Insurance Company.[34] Clay defeated Grundy's former initiative, as well as Grundy's attempt to elect John Adair to the Senate.[34] Clay instead backed the successful candidacy of Buckner Thruston, who also hailed from the Bluegrass Region.[34] Clay also advocated for internal improvements, which would become a consistent theme throughout his public career.[34]

First Senate appointment

Clay's influence in Kentucky state politics was such that in 1806 the Kentucky legislature elected him to the Senate seat of John Breckinridge, who had resigned when appointed as US Attorney General. The legislature first chose John Adair to complete Breckinridge's term, but he had to resign over his alleged role in the Burr Conspiracy.[36] On December 29, 1806, Clay was sworn in as senator, serving for slightly more than two months[37] During his brief tenure, Clay advocated for the construction of various bridges and canals, including a canal connecting the Chesapeake Bay and the Delaware River.[38] Though he did not remain in Washington long, Clay won numerous friends and established a reputation as a diligent worker and an entertaining public speaker.[38]

When elected by the legislature, Clay was below the constitutionally required age of thirty. His age did not appear to have been noticed by any other Senator, and perhaps not by Clay.[37] His term ended before his thirtieth birthday.[39] Such an age qualification issue has occurred with only two other U.S. Senators, Armistead Thomson Mason (aged 28 in 1816), and John Eaton (aged 28 in 1818). Such an occurrence, however, has not been repeated since.[40] In 1934, Rush D. Holt, Sr. was elected to the Senate at the age of 29; he waited until he turned 30 (on the following June 19) to take the oath of office. In November 1972, Joe Biden was elected to the Senate at the age of 29, but he reached his 30th birthday before the swearing-in ceremony for incoming senators in January 1973.[41]

Speaker of the State House and duel with Humphrey Marshall

When Clay returned to Kentucky in 1807, he was elected as the Speaker of the state House of Representatives.[42] As part of the Napoleonic Wars, the British intercepted American ships suspected of trading with France and forcibly conscripted American sailors into their navy.[43] President Jefferson responded by passing the Embargo Act of 1807, which sought to cut off trade with foreign powers.[43] In support of Jefferson's policy, Clay introduced a resolution to require members to wear homespun suits rather than those made of imported British broadcloth.[43] Two members voted against the measure.[44] One was Humphrey Marshall, an "aristocratic lawyer who possessed a sarcastic tongue," who had been hostile toward Clay in 1806 during the trial of Aaron Burr.[44]

On January 4, 1809 Clay and Marshall nearly came to blows on the Assembly floor, and Clay challenged Marshall to a duel. It was still used as a method of settling disputes of honor. It took place on January 19. Apparently to keep any blood from being spilled in their home state of Kentucky,[45] they had chosen a dueling ground in Indiana, directly across the Ohio River from what was then Shippingport, Kentucky and near the mouth of Silver Creek.[46][47][48] While many contemporary duels were called off or fought without the intention of killing one another, both Clay and Marshall planned on killing their opponent.[49]

They each had three turns to shoot.[44] Clay grazed Marshall once, just below the chest.[44] Marshall hit Clay once in the thigh.[44] Both survived.[44] Clay quickly recovered from his injury, and received only a minor censure from the Kentucky legislature.[50]

Second Senate appointment

In 1810, United States Senator Buckner Thruston resigned to serve as a judge on the United States Circuit Court, and Clay was selected by the legislature to fill the seat for the fourteen months remaining on the term.[51] In his first speech, Clay called for a more aggressive policy towards Britain.[51] On the insistence of the Kentucky legislature, Clay helped prevent the re-charter of the First Bank of the United States, arguing that it interfered with state banks and infringed on states' rights.[52] Clay also advocated the annexation of West Florida, which the Spanish also claimed.[53] After serving in the Senate for one year, Clay decided that he disliked the rules of the Senate.[51] Though he felt confident that he could win election to a full Senate term, Clay instead chose to seek election to the United States House of Representatives.[51] He easily won the election.[51]

Speaker of the House

During the fourteen years following his first election, Clay was re-elected five times to the House and to the speakership.[54] Clay's re-election as Speaker was aided by the weakness of the Federalist Party, which failed to win control of either chamber of Congress after 1801. Clay's tenure in the House was interrupted from 1814 to 1815, when he traveled to Europe to negotiate a peace treaty with the British, and from 1821 to 1823, when Clay briefly retired to rebuild his family's fortune in the aftermath of the Panic of 1819.[55] With a tenure of ten years and 196 days, Clay served more than twice as long as any other pre-Civil War Speaker. Only Sam Rayburn has occupied the office for a longer amount of time.

Election

Clay joined the United States House of Representatives in 1811. Clay was one of several young representatives elected in the 1810 elections. Many of these young Congressmen took a belligerent position towards Britain, and Clay was among them.[56] Buoyed by the support of this War Hawk faction, Clay was elected Speaker of the House.[56][57] He was chosen Speaker on the first day of his first session, something never done before or since (except for the first ever session of Congress back in 1789). At 34, Clay also became the youngest Speaker,[56] though Robert M. T. Hunter would later win that distinction. Like other Southern Congressmen, Clay took domestic slaves to Washington, DC to support his household. The slaves included Aaron and Charlotte Dupuy, their son Charles, and daughter Mary Ann.[58]

Changes as Speaker

As Speaker, Clay wielded considerable power in making committee appointments, and, like many of his predecessors, he appointed his allies to important committees.[59] However, Clay was exceptional in his ability to control the legislative agenda through well-placed allies and the establishment of new committees.[59] Clay also departed from precedent by frequently taking part in floor debates.[59] Clay's drive to increase the power of the office Speaker was aided by President James Madison, who similarly believed in the supremacy of Congress in most matters.[60] John Randolph, a fellow Republican but also a member of the tertium quids group that opposed many federal initiatives, emerged as a prominent opponent of Speaker Clay.[61] While Randolph frequently attempted to obstruct Clay's initiatives, Clay became a master of parliamentary maneuvers that enabled him to advance his agenda even over the attempted obstruction of Randolph and others.[62]

War of 1812 and the Treaty of Ghent

On taking office, Clay and his war hawks demanded that the British revoke the Orders in Council, a series of decrees that resulted in a commercial war with the United States.[63] Clay also strongly supported the expedition of William Henry Harrison against the forces of the Native American leader Tecumseh, and Clay celebrated Harrison's victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811.[63] With a possible war looming, Clay helped pass President Madison's request to raise armies and navies, though the naval expansion was not as large as Clay had called for.[64] When Madison called for war, Clay led the House to a quick passage of a declaration of war against Britain.[65] Madison signed the declaration of war on June 18, 1812, and the War of 1812 began. During the war, Clay frequently communicated with Secretary of State James Monroe and Secretary of War William Eustis, though he advocated for the replacement of the latter.[66] Frustrated at Eustis's perceived inaction, Clay urged William Henry Harrison to reinforce the American force at the Siege of Detroit.[66] The war started poorly for the Americans and for Clay, who lost friends and relatives in the fighting.[67] However, in October 1813, the British asked Madison begin negotiations in Europe, and Madison asked Clay to join his diplomatic team.[68] Madison hoped that the presence of the leading War Hawk would ensure that Americans looked favorably on a peace treaty.[68] Clay was reluctant to leave Congress, but chose to felt duty-bound to accept the offer, and so he resigned from Congress on January 19, 1814, and prepared to travel to Europe.[68]

Though Clay left the country on February 25, negotiations with the British did not begin until August.[69] Clay was part of a team of five commissioners, which also included Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, Senator James Bayard, ambassador Jonathan Russell, and ambassador John Quincy Adams, the nominal head of the American team.[69] Clay and Adams maintained an uneasy relationship marked by frequent clashes, and Gallatin emerged as the unofficial leader of the American commission.[70] When the British finally presented their initial peace offer, Clay was outraged by its terms, especially the British proposal for an Indian barrier state.[71] After a series of American military successes in 1814, and coupled with growing British reluctance to fight in the United States, the British delegation made several concessions.[72] However, Clay continued to fight them on the issue of Mississippi River navigation rights, judging that the British wanted peace more than they were letting on; Clay was proven right when the British offered an even better deal.[72] The Treaty of Ghent was signed on December 24, 1814, ending the war.[3] Clay briefly traveled to Paris and then London, where he helped Gallatin negotiate a commercial agreement with the British.[73] Clay finally returned to the United States in September 1815.[74] Despite his absence, Clay's constituents elected him in 1814 to another term.[75] Clay declined Madison's offer of an appointment as minister to Russia, and Clay won another term as Speaker of the House.[75]

Work in Liberia

Henry Clay helped establish and became president in 1816 of the American Colonization Society, a group that wanted to establish a colony for free American blacks in Africa; it founded Monrovia, in what became Liberia, for that purpose. The group was made up of both abolitionists from the North, who wanted to end slavery, and slaveholders, who wanted to deport free blacks to reduce what they considered a threat to the stability of slave society. On the "amalgamation" of the black and white races, Clay said that "The God of Nature, by the differences of color and physical constitution, has decreed against it."[76] Clay presided at the founding meeting of the ACS on December 21, 1816, at the Davis Hotel in Washington, D.C. Attendees included Robert Finley, James Monroe, Bushrod Washington, Andrew Jackson, Francis Scott Key, and Daniel Webster.

The American System

On his return to the House, President Madison called for an ambitious domestic package, including the protection of domestic manufacturing, infrastructure investment, a stable currency, and a fairly large standing army and navy.[77] Clay eagerly embraced this program, which had much in common with Federalist proposals of the past.[77] After the conclusion of the War of 1812, British factories were overwhelming American ports with inexpensive goods. With the help of loyal lieutenants John C. Calhoun and William Lowndes, Clay passed the Tariff of 1816, which served the dual purpose of raising revenue and protecting American goods.[77] To stabilize the currency, Clay and Treasury Secretary Alexander Dallas proposed the creation of the Second Bank of the United States, which earned Clay criticism from some who remembered his opposition to the re-chartering of the first such bank.[78] Clay also passed the Bonus Bill of 1817, which would have provided a fund for internal improvements, but Madison vetoed the ground over constitutional concerns.[79] Clay was deeply disappointed by Madison's veto, but was unable to override it.[79]

Clay's national plan, which was rooted in Alexander Hamilton's American School, took on the name "The American System." Described later by Friedrich List, it was designed to allow the fledgling American manufacturing sector, largely centered on the eastern seaboard, to compete with British manufacturing through the creation of tariffs.

Monroe Administration

Like Washington and Jefferson, President Madison decided to retire after two terms, leaving open the Republican nomination for the 1816 presidential election. At the time, the Republicans used a congressional nominating caucus to choose their presidential nominees, giving Congressmen a powerful role in the presidential selection process. Monroe and Secretary of War William Crawford emerged as the two main candidates for the Republican nomination.[80] Clay had a favorable opinion of both individuals, but he worked to ensure that Monroe won the nomination, which he did.[80] In the general election, Monroe easily defeated the Federalist candidate, Rufus King. Clay was offered the position of Secretary of War in the Madison and Monroe administrations.[81] However, Clay strongly desired the office of Secretary of State, and was angered when Monroe instead chose John Quincy Adams.[82] Unfortunately for Clay, Monroe had decided to place a northeasterner into the most prominent Cabinet position, and was also fearful that the appointment of Clay to State would look like a reward for Clay's support in the nominating caucus.[82] Clay became so bitter that he refused to allow Monroe's inauguration to take place in the House Chamber, and subsequently did not attend Monroe's outdoor inauguration.[83]

In foreign policy, Clay was the leading American supporter of independence movements and revolutions in Latin America after 1817. Clay frequently called on the Monroe administration to recognize these republics, which Clay saw as similar to the United States, but Monroe wanted to avoid antagonizing Spain while he planned to acquire Spanish Florida.[84] Between 1821 and 1826, the U.S. recognized all the new countries, except Uruguay (whose independence was debated and recognized only later). When in 1826 the U.S. was invited to attend the Columbia Conference of new nations, opposition emerged, and the American delegation never arrived. Clay supported the Monroe Doctrine, which called for the non-intervention of European powers in the Americas, though Clay was not as pleased with the part of the Monroe Doctrine that called for American non-intervention in European affairs.[85] Clay supported the Greek independence revolutionaries in 1824 who wished to separate from the Ottoman Empire, an early move into European affairs.

In 1818, General Andrew Jackson had crossed into Spanish Florida to suppress raids by Seminole Indians.[86] Though Jackson was following Monroe's orders in entering Florida, he defied the administration's orders by seizing the Spanish town of Pensacola.[86] Despite protestations from Secretary of War Calhoun, Monroe and Adams decided to support Jackson in hopes that his actions would convince Spain to sell Florida.[86] Clay, however, was outraged, as he viewed Jackson's attack as an unconstitutional assumption of the Congressional prerogative to declare war.[87] Jackson in turn saw Clay's protestations as an attack on his character, and thus began a long rivalry between Clay and Jackson.[87] The rivalry and the controversy over Jackson's expedition temporarily subsided after the signing of the Adams–Onís Treaty, which saw the United States purchase Florida and delineate its western boundary with New Spain.[88]

The Missouri Compromise

In 1819, a dispute erupted over the admission of Missouri as a slave state. New York Congressman James Talmadge introduced an amendment that would provide for the gradual emancipation of Missouri's slaves, sparking the ire of southerners.[89] Though Clay had previously called for gradual emancipation in Kentucky, he sided with the southerners in voting down Talmadge's amendment.[89] Clay instead proposed simultaneous statehood for both Missouri and Maine, which was then a part of Massachusetts.[90] Illinois Senator Jesse B. Thomas proposed a compromise, later known as the "Missouri Compromise," in which Missouri would be admitted as a slave state, but elsewhere slavery would be forbidden north of 36° 30' parallel.[90] Thomas's idea won the backing of Clay, who helped the compromise pass the House and defeated a last-second procedural challenge from John Randolph.[90] Further controversy ensued when Missouri's constitution banned free blacks from entering the state.[91] Clay was able to engineer a compromise that allowed Missouri to join as a state in August 1821.[91]

Presidential election of 1824

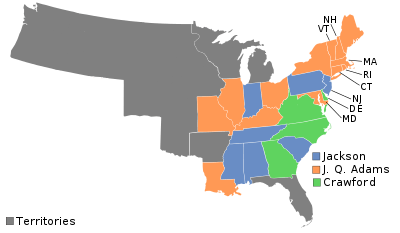

After a brief retirement, Clay won election to the House in 1822, and began considering his first presidential bid.[92] By 1822, several members of the dominant Democratic-Republican Party had begun exploring presidential bids to succeed Monroe, who planned to retire after two terms like his predecessors.[93] The Federalist Party had almost totally collapsed at this point, and the party failed to put forth a presidential candidate. Re-elected as Speaker in 1823, Clay passed the Tariff of 1824 and the General Survey Act, and Clay campaigned on his American System of high tariffs and federal spending on infrastructure.[94] As the election approached, three members of Monroe's Cabinet, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, appeared to be Clay's strongest competitors for the presidency.[93] In 1822, the Tennessee legislature elected General Andrew Jackson to the Senate, and his backers also began to prepare for a presidential candidacy.[95] Though many (including Clay) did not take his candidacy seriously at first, Jackson's emergence threatened Clay's presidential chances, since both candidates had a strong following in the western states.[95] Jackson's supporters devised new campaign strategies by building grassroots networks that bypassed party bosses, signalling the rise of Jacksonian democracy.[96] Crawford won the Republican congressional nominating caucus, which had decided previous Republican nominees, but the caucus had come to be seen as a vestige of elitism and Crawford's caucus victory actually hurt his popularity.[97] In the Fall of 1823, Crawford suffered a major stroke, while Calhoun withdrew after Jackson won the support of the Pennsylvania legislature.[96] The 1824 election thus had four major candidates, all of them Democratic-Republicans: Adams of Massachusetts, Crawford of Georgia, Jackson of Tennessee, and Clay of Kentucky. Ideologically, Adams and Clay both supported a relatively strong federal government, while Crawford and Jackson tended to oppose federal infrastructure projects, instead favoring stronger state governments.[98]

By 1824, with Crawford still in the race, Clay concluded that no candidate would win a majority of electoral votes; such a scenario would require the House of Representatives to decide the election.[99] According to the terms of the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the top three electoral vote-getters would advance to a runoff in the House in which each state delegation would cast one vote. As Speaker of the House, Clay felt confident that he could win a contingent presidential election held in the House.[99] In hopes of winning New York's electoral votes, Clay named former Senator Nathan Sanford as his running mate.[100] Martin Van Buren, a prominent backer of Crawford, asked Clay to serve as Crawford's running mate; Clay declined the offer, but rumors of the offer hurt Clay's presidential candidacy.[100] As election returns came to Washington, Clay rightly assumed that no one had won a majority of electoral votes, and that Jackson and Adams (in either order) would finish first and second in the electoral college.[101] Clay won Kentucky, Ohio, and Missouri, but the failure of Clay's supporters in New York and Louisiana allowed Crawford to finish third.[102] Clay was humiliated that he finished behind the invalid Crawford and Jackson, but supporters of the three remaining presidential candidates immediately began courting his support for the House vote.[103] On January 9, 1825, Clay privately met with Adams for three hours, after which Clay promised Adams his support; both would later claim that they did not discuss Clay's position in an Adams administration.[104] Of the three candidates, Adams was the most sympathetic to Clay's American System, and Clay viewed both Jackson and the sickly Crawford as unsuitable for the presidency.[104] With the help of Clay, Adams won the House vote on the first ballot.[105] After his election, Adams offered Clay the position of Secretary of State, which Clay accepted, despite fears that he would be accused of trading his support for the Cabinet post.[106] Jackson was outraged by the election, and he and his supporters accused Clay and Adams of having reached a "Corrupt Bargain."[106][107]

Secretary of State

The Senate confirmed Clay's nomination to Secretary of State, and Clay remained in that office from 1825 to 1829. However, Clay was deeply wounded by the accusations that he had supported Adams in exchange for the position, and he was hurt, both emotionally and politically, by the attacks on his character.[108] Clay's tenure as Speaker of the House was hampered by near-constant illness, and Clay found his work tedious.[108] Clay did come to like Adams, a former rival, and Clay helped Adams shape his domestic program in the face of Jacksonian attacks.[109] Martin Van Buren, a Jackson ally, pushed the "Tariff of Abominations" through Congress as a ploy to shift the South into the Jackson camp; Clay was aware of Van Buren's machinations but was unwilling to shift his favorable position on high tariffs.[110] Clay sent Albert Gallatin to Britain to attempt to negotiate a commercial treaty and a settlement of the Canada–United States border, though Gallatin proved unsuccessful.[111] Like his predecessors, Clay insisted that the French pay for damages arising from attacks on American shipping during the Napoleonic Wars, but the French refused.[111] Clay was more successful in negotiating commercial treaties with Latin American republics, negotiating "most favoured nation" trading status with Latin American countries in an attempt to ensure that no European country had a trading advantage over the United States.[112] Adams and Clay were both wary of forming entangling alliances with the emerging states, but continued to uphold the Monroe Doctrine which called for European non-intervention in former colonies.[111][113]

Jackson became increasingly popular during the Adams administration, and Adams and Jackson supporters engaged in increasingly-bitter partisan warfare in advance of the 1828 presidential election.[114] Although Adams and Jackson still considered themselves Republicans, Adams followers began to call themselves National Republicans and Jackson's followers "Democrats."[115] Jackson's well-organized followers deftly made use of newspapers to mobilize supporters, while the Adams campaign (including Clay) pursued a letter-writing strategy similar to the campaigns of the past.[116] Adams followers denounced Jackson as a demagogue, and some Adams-aligned papers accused Jackson's wife, Rachel Jackson, of bigamy.[114] Though Clay was not directly involved in these attacks, his failure to denounce them earned him the lifelong enmity of Andrew Jackson.[114] Jackson's followers made up lies about the Adams administration, such as a claim that Adams had turned the White House into a palace.[114] In the presidential election, Jackson took 56% of the popular vote and won almost every state outside of New England; Clay was especially distressed by Jackson's victory in Kentucky.[117] The election result represented not only the victory of a man Clay viewed as unqualified and unprincipled, but also a rejection of Clay's domestic policies.[117] As the Adams administration came to an end, Clay declined an offer to be nominated to the Supreme Court and returned home.[118] Following the end of his tenure as Secretary of State, Clay devoted his time to farming and horsebreeding at his plantation, Ashland.[119]

Slave freedom suit

As Secretary of State, Clay lived with his family and slaves in Decatur House on Lafayette Square. As he was preparing to return to Lexington in 1829, his slave Charlotte Dupuy sued Clay for her freedom and that of her two children, based on a promise by an earlier owner. Her legal challenge to slavery preceded the more famous Dred Scott case by 27 years. The "freedom suit" received a fair amount of attention in the press at the time. Dupuy's attorney gained an order from the court for her to remain in DC until the case was settled, and she worked for wages for 18 months for Martin Van Buren, Clay's successor as Secretary of State and the Decatur House. Clay returned to Ashland with Aaron, Charles and Mary Ann Dupuy.[120][121]

The jury ruled against Dupuy, deciding that any agreement with her previous master Condon did not bear on Clay. Because Dupuy refused to return voluntarily to Kentucky, Clay had his agent arrest her. She was imprisoned in Alexandria, Virginia, before Clay arranged for her transport to New Orleans, where he placed her with his daughter and son-in-law Martin Duralde. Mary Ann Dupuy was sent to join her mother, and they worked as domestic slaves for the Duraldes for another decade.[120]

In 1840 Henry Clay finally gave Charlotte and her daughter Mary Ann Dupuy their freedom. He kept her son Charles Dupuy as a personal servant, frequently citing him as an example of how well he treated his slaves. Clay granted Charles Dupuy his freedom in 1844.[120] While no deed of emancipation has been found for Aaron Dupuy, in 1860 he and Charlotte were living together as free black residents in Fayette County, Kentucky. He may have been freed or "given his time" by one of Clay's sons, as Dupuy continued to work at Ashland, for pay.[58]

Today, Decatur House, in Washington, DC, is a National Historic Landmark and museum on Lafayette Square near the White House and has exhibits on urban slavery and Charlotte Dupuy's freedom suit against Henry Clay.[120]

Senate career

After a period of semi-retirement, Clay returned to federal office in 1831 by winning election to the Senate over Richard Mentor Johnson in a 73 to 64 vote of the Kentucky legislature.[122] His return to the Senate after 20 years, 8 months, 7 days out of office, marks the fourth longest gap in service to the chamber in history.[123] Clay quickly became a major opponent of the Jackson administration and continued to enjoy the reputation of a great public speaker.[124] Clay served in the Senate from 1831 to 1842, and from 1849 to his death in 1852.

Opposition to Jackson

Clay's American System ran into strong opposition from President Jackson's administration. A key point of contention between the two men was over the Maysville Road. It would authorize federal funding for a project to construct a road linking Lexington and the Ohio River; however all of the road would be inside Kentucky. Jackson vetoed it because he felt that it did not constitute interstate commerce, and he feared it would fund corruption. Jackson opposed using the federal government to promote economic modernization, thereby appealing to his agrarian base that wanted rural expansion but distrusted cities.[125]

Clay strongly supported renewal of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States. The bank's charter did not expire until 1836, but bank president Nicholas Biddle asked for renewal in 1831, hoping that election year pressure and support from Secretary of the Treasury Louis McLane would convince Jackson to allow the re-charter.[126] After it became clear that Congress would pass the recharter but Jackson would veto it, Clay and his allies ensured that Jackson would have to veto the bill (rather than use a pocket veto) in the hope that it would hurt Jackson politically.[127] After his 1832 re-election, Jackson suspected that the bank's supporters would again seek to re-charter the bank, and he sought remove federal money from it.[128] After Treasury Secretary William J. Duane refused to authorize the removal of federal money, Jackson successfully sought Duane's resignation and appointed Roger Taney as Duane's replacement.[128] Taney deposited the federal money into "pet banks," and in retaliation, Biddle asked for the repayment of a large number of loans.[128] National Republicans as well as many Democrats were outraged by Jackson's actions, and Clay passed a Senate motion of censure against Jackson.[129]

1832 presidential campaign

With the defeat of Adams, Clay became the leader of the National Republicans.[130] In 1830, Clay began making preparations for a presidential campaign in the 1832 election.[131] Early in Jackson's presidency, many doubted that Jackson would seek a second term, and Clay, Vice President John Calhoun, and former Treasury Secretary William Crawford (whose health had somewhat improved since 1824) all began preparations for the upcoming election.[131] In 1831, Jackson made it clear that he was going to run for re-election, ensuring that support or opposition to his presidency would be a central feature of the upcoming race.[132] While the two previous elections had essentially been intra-party contests among Democratic-Republicans, the election of 1832 saw the development of discrete political parties.[133] Jackson's Democrats rallied around his policies towards the national bank, internal improvements, Indian removal, and nullification, but these policies also earned Jackson various enemies.[133] John C. Calhoun's Nullifier faction opposed Jackson after the president took a strong stance against nullification, but the Nullifiers and National Republicans disagreed about the tariff, limiting the possibility of cooperation.[134] The Anti-Masonic Party, a new political party opposed to Freemasonry, nominated former Attorney William Wirt for president.[135] Clay, himself a Freemason, considered withdrawing from the race in hopes of unifying Jackson's opponents, but he ultimately decided to stay in the race.[135] Inspired by the Anti-Masonic Party's national convention, Clay's followers arranged for a national nominating convention, with the intention of anointing Clay as the National Republican nominee.[136] Facing little opposition at the convention, Clay won the party's presidential nomination, and the convention nominated Pennsylvania Congressman John Sergeant as Clay's running mate.[122] As the election approached, the debate over the re-authorization of the Second Bank of the United States emerged as the most important issue.[133] In his veto of the bank, Jackson effectively made the case that the bank was a tool of the elites, bolstering his popularity with the people.[137]

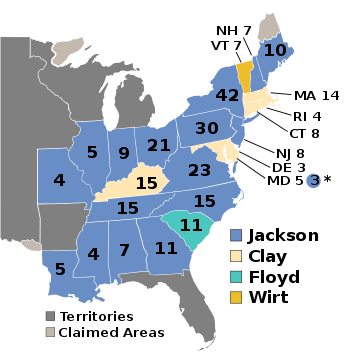

Jackson won 54.2% of the popular vote and 219 of the 286 electoral votes. Clay won just 37.4% of the popular vote, carrying Kentucky and five other states. Wirt won 7.8% of the popular vote and carried Vermont. Governor John Floyd of Virginia won South Carolina's eleven electoral votes.

The Nullification Crisis

The Tariff of 1828, dubbed the "tariff of abominations," had raised tariffs considerably in an attempt to protect fledgling factories. The high tariffs angered John C. Calhoun of South Carolina and his followers, and South Carolina declared its right to nullify federal tariff legislation and cease the assessment of the tariff on imports. The state threatened to secede from the Union if the federal government tried to enforce the tariff laws. Furious, President Jackson threatened to lead an army to South Carolina and hang any man who refused to obey the law.[138]

In 1833, shortly after his defeat in the previous year's presidential election, Clay worked with Calhoun to end the dispute.[139] Though Clay desired a high tariff, he found Jackson's war-like rhetoric against South Carolina distressing, and sought to avoid a crisis that could end in civil war.[138] Working with Calhoun, Clay brokered a deal to lower the tariff gradually, with that deal becoming known Compromise Tariff of 1833.[139] On March 2, 1833, with little choice in the matter, Jackson signed into law the compromise tariff as well as the Force Bill.[140] The compromise tariff helped to preserve the supremacy of the federal government over the states, but the crisis was indicative of the developing conflict between the northern and southern United States over economics and slavery. Clay's role in the compromise, as well as his opposition to Jackson, strongly increased his approval among those in the South.[141]

Formation of the Whig Party

Jackson's policies united his enemies, including southerners, Antimasons, and National Republicans.[142] In an 1834 speech criticizing Jackson, Clay compared Jackson's opposition to the Whigs, a British political party opposed to absolute monarchy.[143] Jackson's opponents took on the name "Whig," which proved to be a more unifying term than "National Republican" had, as the latter term was too closely associated with northern business interests.[143] The Whig Party thus succeeded the National Republicans as the principal opposition party to the Democrats.

Neither the Whigs nor the Democrats were unified geographically or ideologically. However, Whigs tended to favor a stronger legislature, a stronger federal government, a higher tariff, spending on infrastructure, re-authorization of the Second Bank of the United States, moral reform (such as the temperance movement), and publicly-funded education. Conversely, Democrats tended to favor a stronger president, stronger state governments, lower tariffs, hard money, and expansionism. Neither party took a strong national stand on slavery. The Whigs tended to control many newspapers, while Democrats were particularly adept at organizing the masses.[144]

Partly due to grief over the death of his daughter, Anna, Clay chose not to run in the 1836 presidential election, and the Whigs were too disorganized to nominate a single candidate.[145] Four Whig candidates ran against Van Buren: General William Henry Harrison, Senator Hugh Lawson White, Senator Daniel Webster, and Senator Willie Person Mangum. Though Clay privately preferred Webster, he supported Harrison after Harrison emerged as the most popular and prominent Whig candidate.[145] Van Buren won the 1836 election with 50.8 percent of the popular vote and 170 of the 294 electoral votes. Discouraged by the Democratic victory, Clay began pondering retirement from public life.[146] However, Van Buren's presidency was quickly hit by the Panic of 1837, a major recession that badly damaged the Democratic Party, and Clay resumed his status as a Congressional leader.[147]

1840 election and the Harrison presidency

As the 1840 presidential election approached, many expected that the Whigs would win control of the presidency in the aftermath of the Panic of 1837.[148] In 1837, supporters of William Henry Harrison proposed a Whig national convention, and Clay agreed to support the idea.[149] Clay initially viewed Webster as his strongest rival,[150] but Clay, Harrison, and General Winfield Scott emerged as the principal candidates at the 1839 Whig National Convention. Clay's greatest weakness in his bid for the Whig nomination was his lack of strength in the North, as abolitionists and Antimasons both disapproved of Clay.[151] Many Whigs also disliked Clay's American System, and thought that the Whigs ticket would have a better chance being led by a popular military hero rather than a twice-defeated presidential candidate.[152] On the first ballot of the convention, Clay narrowly led Harrison, but Scott also received a solid minority of the vote. During the convention, Thaddeus Stevens, a Pennsylvania Antimason and supporter of Harrison, arranged for the Virginia delegation to receive a letter that showed Scott's anti-slavery views.[153] With Scott's chances badly damaged, Scott's delegates switched to Harrison, giving him the nomination.[153] Seeking to placate Clay's supporters and to balance the ticket geographically, the convention chose Virginia Senator John Tyler, a personal friend of Clay, as the vice presidential nominee.[154] Clay was disappointed by the outcome, but helped Harrison's campaign with numerous speeches.[155] Democrats, meanwhile, nominated Van Buren for a second term. Harrison ran on a campaign that emphasized his personal heroism and Van Buren's failures rather than Whig policies.[156] With Van Buren still damaged by the Panic of 1837, Harrison won 52.9% of the vote and 234 of the 294 electoral votes.

Harrison asked Clay to serve another term as Secretary of State, but Clay declined, seeking instead to lead the new Whig Congressional majority.[157] Webster was instead chosen as Secretary of State, while John J. Crittenden, a close Clay ally, was chosen as Attorney General.[157] As Harrison prepared to take office, Clay and Harrison clashed over the leadership of the Whig Party, with Harrison sensitive to accusations that he would answer to Clay.[158] After initially resisting Clay's pleas to call a special session of Congress (the first regular session of Congress was set to begin on December 1841), Harrison finally consented and called for a session of Congress to begin in May 1841.[159] Shortly after calling for the special session of Congress, Harrison died of pneumonia (or possibly enteric fever) on April 4, 1841.[160]

Tyler Administration

Tyler had joined the Whig ticket largely due to his perceived personal closeness with Clay, but he quickly proved to have political views of his own.[161] Tyler retained Harrison's Cabinet, but quickly made it known that he had reservations about re-establishing a national bank, a key priority of Clay's.[162] Clay saw the re-establishment of a national bank as policy in reviving the weak national economy, and Clay sought to compromise with Tyler to create national bank legislation that the president would not veto.[163] In August 1841, Tyler was presented with a bill that incorporated some of Tyler's proposals.[164] Tyler vetoed the bill over concerns that the national bank would compete with state banks.[164] After Tyler told Whig Congressman Alexander Stuart that he would sign a similar bill that addressed his concerns, Congressional Whigs wrote another bill that they hoped would satisfy Tyler.[165] On September 9, Tyler vetoed this bill as well.[166] Tyler's second veto infuriated his fellow Whigs, and Tyler's Cabinet resigned, with the exception of Secretary of State Daniel Webster.[167] Reflecting his belief in legislative supremacy and his anger at Tyler's actions, Clay unsuccessfully proposed Constitutional amendments removing the president's veto power and giving Congress the authority to appoint the Secretary of the Treasury.[168]

In February 1842, with the United States facing a looming budget crisis, Clay proposed a detailed economic plan that combined budget cuts with an increased tariff.[169] Clay then resigned, orchestrating the selection of Crittenden as his successor, and began to prepare for another presidential campaign.[169] Clay remained in close contact with Congress and Congressional Whigs managed to pass many of Clay's proposals, but Tyler again vetoed them.[170] Ultimately Tyler and the Whig Congress would compromise on the Tariff of 1842. Though Clay was distressed over the disagreements with Tyler, Tyler's apostasy, combined with Webster's continuing affiliation with Tyler, positioned Clay as the natural Whig candidate for the 1844 presidential election.[171] Supporters of Webster (who resigned from Tyler's Cabinet in 1843), Scott, and Supreme Court Justice John McLean called for another Whig national convention, and Clay assented, partly because it would relieve him of the delicate task of selecting a running mate.[172] Clay quietly favored New York Congressman Millard Fillmore for the position, and made it clear that he did not want Webster as his running mate, as Clay was angered by Webster's association with Tyler.[172]

1844 and 1848 presidential elections

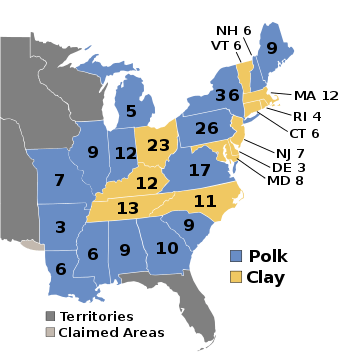

As Tyler continued to oppose Whig priorities, the possibility of a party switch or third-party run by Tyler loomed.[173] Tyler sought to create a new party opposed to both Clay and Van Buren, the presumed Democratic nominee.[174] Tyler's plans delighted many Whigs who thought that Tyler's efforts would prove more damaging to the Democrats.[174] As 1844 approached, Clay wanted to focus on economic issues, especially the recovering economy which they argued was a result of the Tariff of 1842.[174] However, nativism and the annexation of Texas emerged as major issues during the 1844 election, with the latter in particular upending the race.[174] Clay refused to take a position on the annexation of Texas, as support for annexation would have offended the North and opposition would have offended the South.[175] Clay also called for a conciliatory policy towards Britain regarding the Oregon Question, as he argued that demographics and geography would eventually compel the British to give up their claims on the region.[175] After President Tyler concluded an annexation treaty with Texas, Clay announced his opposition to the annexation, stating his belief that the United States should focus on developing territory already part of the Union, and arguing that annexation would cause sectional tensions over slavery.[176] Perhaps coincidentally, on the same day that Clay published a letter announcing his opposition to the annexation, Van Buren published a similar letter.[177] Clay unanimously won the presidential nomination at the 1844 Whig National Convention, but southern Democrats successfully opposed Van Buren's nomination, and the 1844 Democratic National Convention instead chose former Speaker of the House James K. Polk.[178] Unlike Van Buren and Clay, Polk supported the annexation of Texas.[178]

Clay was surprised by Van Buren's defeat but remained confident of his chances in the 1844 election, and Whigs mocked Polk for his relative obscurity.[179] However, Polk, a former Governor of Tennessee, convinced Tyler to drop out of the race and effectively courted the various factions of Democrats.[179] Clay's running mate, Theodore Frelinghuysen, was attacked for his affiliation with anti-Catholic groups.[179] In July, Clay wrote two letters in which he attempted to clarify his position on the annexation of Texas, and Democrats attacked his supposedly inconsistent position.[180] Polk won the election, taking 49.5% of the popular vote and 170 of the 275 electoral votes. Had Clay won New York, which Polk won by a margin of 38,000 votes out of a total of 2.7 million votes, Clay would have won the election.[181] The North and South would come to increased tensions during Polk's presidency over the extension of slavery into Texas and beyond.[182] Clay's son, Henry Clay, Jr., died in the Mexican-American War, fighting under the command of General Zachary Taylor at the Battle of Buena Vista.[183] Defeated yet again, Clay returned to his career as an attorney, and a stream of donations helped Clay retire much of the debt he and his son, Thomas, had accumulated.[184]

In the lead-up to the 1848 presidential election, Clay refused to publicly commit to another candidacy, saying that he would only seek the office if he retained the support of his fellow Whigs.[185] Having suffered numerous losses, many younger Whigs sought new leaders who could win over Democrats and other non-Whigs.[186] Webster, Ohio Senator Thomas Corwin, Associate Justice John McLean, and Generals Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor emerged as potential challengers for the Whig nomination.[186] Clay's health was also an issue, as Clay turned 70 in 1847, and Clay may have suffered from early-stage tuberculosis in the late 1840s.[187] However, the successful 1846 elections convinced many Whigs that Clay and his classic Whig principles deserved another chance, and Clay remained interested in another run.[186] After his victories in the Mexican-American War, Taylor experienced a surge of popularity; despite his largely unknown political views, Whigs viewed him as their strongest possible candidate.[188] Even Clay's long-time ally, John Crittenden, abandoned Clay's potential candidacy in favor of Taylor[188]

In November 1847, Clay delivered a speech that was harshly critical of the Mexican-American War and President Polk, signalling the start of his own 1848 candidacy.[189] Clay called for no acquisition of territory from Mexico, thereby avoiding the possibility of adding new slave territories and winning some northern support for his candidacy.[190] To quell rumors that he did not intend to seek the presidency, Clay issued a nationally-published statement of his intent to seek the 1848 Whig nomination, an unprecedented and unpopular act at a time when politicians were supposed to adhere to the fiction that they were reluctant recruits for office.[191] The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War and ceded new lands to the United States. Clay was unwilling to endorse the anti-slavery Wilmot Proviso, alienating his northern supporters, and he was unable to win back the support of southern Whigs.[192] Clay narrowly trailed Taylor after the first ballot of the 1848 Whig National Convention, and Taylor eventually won the presidential nomination the fourth ballot.[193] Partially in an attempt to please the Clay wing of the party, the convention nominated Millard Fillmore as Taylor's running mate.[193] The Taylor-Fillmore ticket won 47.3% of the popular vote and 163 of 290 electoral votes. Democratic nominee Lewis Cass won 45.5% of the popular vote, while former President Van Buren, running on the Free Soil ticket, won 10.1% of the popular vote. Unlike the election of 1840, Clay did not campaign on behalf of the Whig nominee, and he was embittered by his failure to win the nomination.[194]

Clay received a significant share of the presidential electoral vote in three separate elections, a feat matched only by John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Grover Cleveland, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Richard Nixon, and William Jennings Bryan, with only the latter (like Clay) failing to win a presidential election.

Final Senate term

Increasingly worried about the sectional tensions arising over the issue of slavery in newly acquired territories, Clay accepted election to the Senate in 1849.[195] President Taylor and the 31st United States Congress faced several vexing problems regarding the disposition of lands acquired in the Mexican-American War.[196] Taylor initially pursued a policy of "non-action," hoping to avoid slavery debates by immediately admitting the new territory as states.[197] Clay played little role in the formation of Taylor's Cabinet, and was not closely involved in forming Taylor's presidential initiatives.[198] In January 1850, with Congress still deadlocked regarding the status of the Mexican Cession, Clay decided to propose a compromise designed to ease sectional tensions and organize territory acquired in the Mexican-American War.[199] After Taylor's death, President Fillmore consulted with Clay in appointing a new Cabinet.[200] Some of Clay's friends proposed that he prepare to run in the 1852 presidential election, but Clay dismissed the possibility due to his declining health.[201]

The Compromise of 1850

Clay played a central role in designing a compromise in 1850 between North and South to resolve the increasingly dangerous slavery question. He acquired the help of Senator Stephen A. Douglas, a first-term Democrat from Illinois, to help guide the measures through Congress and thus prevent civil war.[202]

On January 29, 1850, Clay proposed a series of resolutions, which he considered to reconcile Northern and Southern interests, what would widely be called the Compromise of 1850. Clay originally intended the resolutions to be voted on separately, but at the urging of southerners he agreed to the creation of a Committee of Thirteen to consider the measures. The committee was formed on April 17. On May 8, as chair of the committee, Clay presented an omnibus bill linking all of the resolutions.[203][204] The resolutions included:

- Admission of California as a free state, ending the balance of free and slave states in the Senate.

- Organization of the Utah and New Mexico territories without any slavery provisions, giving the right to determine whether to allow slavery to the territorial populations.

- Prohibition of the slave trade, though not the ownership of slaves, in the District of Columbia.

- A more stringent Fugitive Slave Act.

- Establishment of boundaries for the state of Texas in exchange for federal payment of Texas's ten million dollar debt.

- A declaration by Congress that it did not have the authority to interfere with the interstate slave trade.[205]

The bill was opposed for different reasons by hardliners on both sides. Senator John C. Calhoun composed a speech arguing against the compromise and warning of the possibility of disunion. Calhoun was too ill to read the speech, and Virginia Senator James Murray Mason did so for him on March 4. Clay's original proposal had banned slavery in all of the Mexican Cession, but he dropped this in favor of popular sovereignty, winning the support of many centrist southerners.[206] Many of the more anti-slavery northerners, such as New York Senator William H. Seward, opposed the compromise as well.[207] However, on March 7, Daniel Webster gave a speech in which he argued in favor of the compromise.[208] President Taylor, who had opposed the compromise from the start, died in June 1851, and he was succeeded by Millard Fillmore.[209] Fillmore signaled his support for the compromise, offering a huge boost to its chances.[200]

The omnibus bill, despite Clay's efforts, failed in a crucial vote on July 31 with the majority of his Whig Party and many Southern Democrats opposed. Clay announced on the Senate floor the next day that he intended to persevere and pass each individual part of the bill. Clay was physically exhausted; the tuberculosis that would eventually kill him had begun to take its toll. Clay left the Senate to recuperate in Newport, Rhode Island. Douglas separated the bills and guided them through the Senate. Each individual bill managed to pass, because it had the support not only of moderates, but of either the pro-slavery or anti-slavery senators, depending on who the bill was meant to favor. Combined, these two groups were able to crush the third.[210]

Clay was given much of the credit for the Compromise's success. It quieted the controversy between Northerners and Southerners over the expansion of slavery, and helped delay secession and civil war until the 1860s. Senator Henry S. Foote of Mississippi, who had suggested the creation of the Committee of Thirteen, later said, "Had there been one such man in the Congress of the United States as Henry Clay in 1860–'61 there would, I feel sure, have been no civil war."[211]

Death and estate

In December 1851, with his health declining, Clay announced that he would resign from the Senate in September 1852.[212] On June 29, 1852, Clay died of tuberculosis in Washington, D.C., at the age of 75. Theodore Frelinghuysen, Clay's running mate in the election of 1844, gave the eulogy at Clay's funeral. He was buried in Lexington Cemetery.[213] Clay's headstone reads: "I know no North—no South—no East—no West." The 1852 pro-slavery novel[214] Life at the South; or, "Uncle Tom's Cabin" As It Is, by W.L.G. Smith, is dedicated to his memory.[215] However, Clay's will freed all the slaves he held at the time of his death.[212]

By the time of his death, his only surviving children were sons Theodore, Thomas, James Brown Clay and John Morrison Clay, who inherited the estate and took portions for use. For several years (1866–1878), James Clay allowed the mansion to be used as a residence for the regent of Kentucky University, forerunner of the University of Kentucky and present-day Transylvania University. The mansion and estate were later rebuilt and remodeled by Clay's descendants. John Clay designated his portion of the estate as Ashland Stud, which he devoted to breeding thoroughbred horses.

Reputation and legacy

Clay's Whig Party collapsed shortly after his death, but Clay cast a long shadow over the generation of political leaders that presided over the Civil War. Mississippi Senator Henry S. Foote stated his opinion that "had there been one such man in the Congress of the United States as Henry Clay in 1860-'61 there would, I feel sure, have been no civil war."[216] Abraham Lincoln, a Whig leader in Illinois, was a great admirer of Clay, saying he was "my ideal of a great man." Lincoln wholeheartedly supported Clay's economic programs.[217] Prior to the Civil War, Lincoln and Clay held similar views about slavery and the union, each calling for gradual emancipation and resettlement of African-Americans.[217] Clay's protege and fellow Kentuckian, John J. Crittenden, attempted to keep the Union together with the formation of the Constitutional Union Party and the proposed Crittenden Compromise. Though Crittenden's efforts were unsuccessful, Kentucky remained in the Union during the Civil War, reflecting in part Clay's continuing influence.[218] In 1957, a Senate Committee selected Clay as one of the five greatest U.S. Senators, along with Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, Robert La Follette, and Robert A. Taft.[219]

Maintained and operated as a museum, today Clay's estate of Ashland includes 17 acres (6.9 ha) of the original estate grounds. It is located on Richmond Road (US 25) in Lexington. It is open to the public (admission charged).

Monuments and memorials

- Memorial column and statue at his tomb in Lexington, Kentucky

- Henry Clay Blvd. and Clay Avenue in Lexington, Kentucky

- Henry Clay statue and portrait in Virginia State Capitol in Richmond, Virginia

- Henry Clay monument in Pottsville, Pennsylvania[220]

- Clay Streets in numerous cities, including New Haven, Connecticut, Richmond, Virginia, Vicksburg, Mississippi and Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin.

- Mount Clay in the Presidential Range of New Hampshire was named for Clay, since renamed Mount Reagan by the state legislature but not by the federal Board on Geographic Names

- Sixteen Clay counties in the United States, in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia. (Clay County, Iowa is named for his son.)

- Ashland Ave. in Chicago, Illinois; Ashland, Virginia, Ashland County in Ohio and Wisconsin were named for his estate, as were the cities of Ashland in Kentucky, Alabama, and Pennsylvania.

- Ashland, Missouri, was named after Clay's Lexington, Kentucky estate, and Henry Clay Blvd was named for him in the same city.

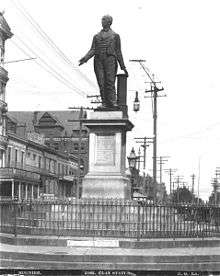

- In New Orleans: uptown – Henry Clay Avenue, and downtown – a 20-foot-tall monument erected in 1860 at Canal Street and St. Charles Avenue/Royal Street, and moved to the center of Lafayette Square in 1901.

- Many schools throughout the U.S., including Clay High School in South Bend, Indiana, Henry Clay High School in Lexington, Kentucky,[221] Henry Clay Middle School in Los Angeles, California, Henry Clay Elementary School in the Hegewisch neighborhood in Chicago, Henry Clay School in Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin and Henry Clay Elementary School in his birthplace, Hanover County, Virginia.

- The Instituto Educacional Henry Clay in Caracas, Venezuela, a bilingual private school

- The Clay Dormitory at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky

- The Lafayette class submarine USS Henry Clay (SSBN-625), the only ship of the United States Navy named in his honor, although the USS Ashland (LSD-1) and USS Ashland (LSD-48) are named for his estate

- Clay, New York, including the road Henry Clay Blvd.

- Henry Clay Village, or Breck's Mill Area, on the left bank of Brandywine Creek in Wilmington, Delaware, factory and mill worker's residences.

- Clay is one of the many senators honored with a cenotaph in the Congressional Cemetery.

- Between 1870 and 1908, Clay was invariably included in the pantheon of Great Americans presented on U. S. definitive postage stamps: he appeared on the 12¢ denomination in the issues of 1870, 1873 and 1879 and on the 15¢ denomination in the issues of 1890, 1894, 1898 and 1902. He has since been honored by the United States Postal Service with a 3¢ Great Americans series postage stamp.

- The town of Claysburg in central Pennsylvania is named in honor of Clay.

- Cooper's Rock State Forest in West Virginia features a preserved nineteenth century iron furnace named in commemoration of Henry Clay.

- Clayville, Illinois was an active settlement during the statesman's life.

- Claysville, Alabama is named in honor of Clay.

- The Henry Clay, an historic upscale residential building in downtown Louisville, KY, formerly the city's YWCA building.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 25.

- ↑ Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 22, 26.

- 1 2 3 Henry Clay Biography: The Great Compromiser, Biography.com.

- 1 2 Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 5.

- ↑ Henry Clay: The Great Compromiser By Howard Walter Caldwell, Graeme Mercer Adam, Charles Keyser Edmunds pg. 5

- ↑ David S. Heidler, David S. Heidler; Jeanne T. Heidler, Jeanne T. Heidler (2010). "Chapter 1 - The Slashes". Henry Clay: The Essential American. Random House Publishing Group. p. ebook. ISBN 9781588369956. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

Henry Clay was a member of the sixth generation of a family that had been in colonial Virginia for more than a hundred and fifty years. John Clay was the first of that line, emigrating from England around 1612.

- ↑ Van Deusen, 4.

- 1 2 Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 6.

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 9-10

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 11-13

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 13-15

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 19-20

- ↑ Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 7.

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 20-21

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 23

- ↑ Schurz, Carl (1915). Henry Clay, Volume 1. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 24-25

- 1 2 Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 12.

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 402

- ↑ "Madeline McDowell Breckenridge (Women in Kentucky – Reform)". Kentucky Commission on Women. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- 1 2 3 Heidler, pg. 27-29

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 30-31

- ↑ "Death of Henry Clay: Sketch of His Life and Public Career", New York Times. June 30, 1852, p. 1.

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 43

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 41-42

- ↑ Kinkead, Elizabeth Shelby (1896). A history of Kentucky. American book company. p. 111. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ↑ Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 15.

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 156

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 53

- 1 2 3 Heidler, pg. 33-36

- ↑ Also known as the "Republican Party," not to be confused with the modern Republican Party

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 34

- ↑ Jerry Hensley, Henry Clay: Compromise and Ambition, Outskirts Press, 2013, page 79

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heidler, pg. 48-51

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 48-52

- ↑ Smucker, Isaac. "Kentucky – Early History", National Magazine: A Monthly Journal of American History, Volume 12, page 462.

- 1 2 Schurz, Carl. Life of Henry Clay, pages 38–39.

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 64-67

- ↑ See Finlay, Luke. "THE CASE OF HENRY CLAY.; Records of the Senate Show No Question Raised as to His Age", Letter to Editor, New York Times (1935-07-20): "How can we make a precedent of their unconscious failure to pass upon the matter?".

- ↑ 1801–1850, November 16, 1818: Youngest Senator. United States Senate. Retrieved November 17, 2007

- ↑ "Rand Paul & Joe Biden in Senate Chambers". January 10, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ↑ Henry Clay – Famous American Biographies.

- 1 2 3 Heidler, pg. 70-71

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 17.

- ↑ Remini (1991), page 55

- ↑ Scott, Samuel Scott (New Albany Rotary Club) (c. 1950s). "New Albany Suburb Famous Field of Honor in Early Days" (PDF). New Albany Floyd County Public Library. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ↑ "The Duels at Silver Creek (Historical Series of New Albany)" (PDF). Historical Series of New Albany (Volume III, No. 8). New Albany Floyd County Public Library (originally broadcast on Radio Station WLRP/WOW/WHEL). Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ↑ James F. Hopkins, ed. (1959). The Papers of Henry Clay, Volume 1 (1797–1814). University Press of Kentucky. p. 613.

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 72-73

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 74

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heidler, pg. 76-78

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 81-83

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 79-81

- ↑ Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 23.

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 148-149

- 1 2 3 Heidler, pg. 85

- ↑ Eaton, Clement (1957). Henry Clay and the Art of American Politics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 24.

- 1 2 "Aaron and Charlotte Dupuy", Isaac Scott Hathaway Museum of Lexington, Kentucky.

- 1 2 3 Heidler, pg. 86

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 88-89

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 87-88

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 96

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 89-90

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 90-92

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 97-98

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 99-101

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 103-104

- 1 2 3 Heidler, pg. 107-108

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 108-111

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 110-115

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 112-113

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 116-117

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 117

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 119

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 121-122

- ↑ Eaton (1957) p. 133.

- 1 2 3 Heidler, pg. 123-125

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 125-126

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 132-133

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 126-127

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 129-130

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 133-134

- ↑ Remini (1991), 150-151

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 136-137

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 165

- 1 2 3 Heidler, pg. 137-138

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 141-142

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 143

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 143-144

- 1 2 3 Heidler, pg. 147-148

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 150-152

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 158-159

- 1 2 Heidler, 155-157

- ↑ Heidler, 166-168

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 160-161

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 162-164

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 162, 164-165

- ↑ Gammon, Samuel Rhea (1922). The Presidential Campaign of 1832, Issues 1-4. John Hopkins Press. pp. 13–15. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 168

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 171

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 172-173

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 174-175

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 176

- 1 2 Heidler, pg. 179-180

- ↑ Heidler, pg. 183-184

- 1 2 Heidler, pg 184-185