Indian copper plate inscriptions

Indian copper plate inscriptions play an important role in the reconstruction of the history of India. Prior to their discovery, historians were forced to rely on ambiguous archaeological findings such as religious text of uncertain origin and interpretations of bits of surviving traditions, patched together with travel journals of foreign visitors along with a few stone inscriptions. The discovery of Indian copper plate inscriptions provided a relative abundance of new evidence for use in evolving a chronicle of India's elusive history.

History

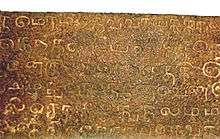

Indian copper plate inscriptions (tamarashasana), usually record grants of land or lists of royal lineages carrying the royal seal, a profusion of which have been found in South India. Originally inscriptions were recorded on palm leaves, but when the records were legal documents such as title-deeds they were etched on a cave or temple wall, or more commonly, on copper plates which were then secreted in a safe place such as within the walls or foundation of a temple, or hidden in stone caches in fields. Plates could be used more than once, as when a canceled grant was over-struck with a new inscription. These records were probably in use from the first millennium. The earliest authenticated plates were issued by the Pallava dynasty kings in the 4th century AD and are in Prakrit and Sanskrit. An example of early Sanskrit inscription in which Kannada words are used to describe land boundaries, are the Tumbula inscriptions of Western Ganga Dynasty, which have been dated to AD 444 according to a 2004 Indian newspaper report.[1] Rare copper plates from the Gupta period have been found in North India. The use of copper plate inscriptions increased and for several centuries they remained the primary source of legal records.[2]

Most copper plate inscriptions record title-deeds of land-grants made to Brahmanas, individually or collectively. The inscriptions followed a standard formula of identifying the royal donor and his lineage, followed by lengthy honorifics of his history, heroic deeds, and his extraordinary personal traits. After this would follow the details of the grant, including the occasion, the recipient, and the penalties involved if the provisions were disregarded or violated. Although the profusion of complimentary language can be misleading, the discovery of copper plate inscriptions have provided a wealth of material for historians[2][3]

Tirumala Venkateswara Temple have a unique collection of about 3000 copper plates on which the Telugu Sankirtans of Tallapaka Annamacharya and his descendants are inscribed.[4]

Tamil copper-plate inscriptions

Tamil copper-plate inscriptions are engraved copper-plate records of grants of villages, plots of cultivable lands or other privileges to private individuals or public institutions by the members of the various South Indian royal dynasties.[5] The study of these inscriptions has been especially important in reconstructing the history of Tamil Nadu.[6] The grants range in date from the 10th century C.E. to the mid 19th century C.E. A large number of them belong to the Chalukyas, the Cholas and the Vijayanagar kings. These plates are valuable epigraphically as they give us an insight into the social conditions of medieval South India; they also help us fill chronological gaps in the connected history of the ruling dynasties. For example the Leyden grant (so called as they are preserved in the Museum of Leyden in Holland) of Parantaka Chola and those of Parakesari Uttama Chola are among the most important, although the most useful part, i.e., the genealogical section, of the latter's plates seems to have been lost.

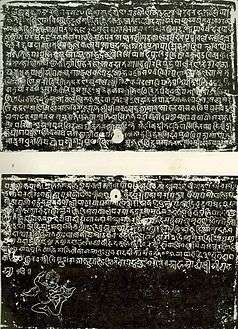

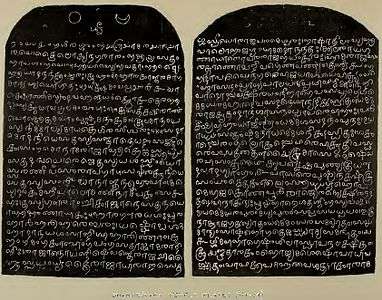

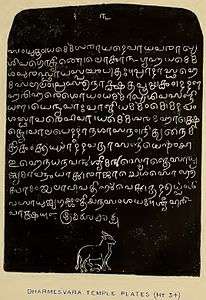

- Vijaynagar Tamil Copper Plate Inscriptions at the Dharmeshwara Temple, Kondarahalli, Hoskote

-

Plate 1 and Back

-

Plate 2[1]

- ^ Rice, Benjamin Lewis (1894). Epigraphia Carnatica: Volume IX: Inscriptions in the Bangalore District. Mysore State, British India: Mysore Department of Archaeology. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

Unlike the neighbouring states where early inscriptions were written in Sanskrit and Prakrit, the early inscriptions in Tamil Nadu used Tamil [7] along with some Prakrit. Tamil has the extant literature amongst the Dravidian languages, but dating the language and the literature precisely is difficult. Literary works in India were preserved either in palm leaf manuscripts (implying repeated copying and recopying) or through oral transmission, making direct dating impossible.[8] External chronological records and internal linguistic evidence, however, indicate that extant works were probably compiled sometime between the 4th century BCE and the 3rd century CE.[9][10][11] Epigraphic attestation of Tamil begins with rock inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE, written in Tamil-Brahmi, an adapted form of the Brahmi script.[12][13] The earliest extant literary text is the Tolkāppiyam, a work on poetics and grammar which describes the language of the classical period, dated variously between the 5th century BCE and the 2nd century CE.

Copper plates of Kerala

Between the eighth and tenth centuries, rulers on the Malabar Coast awarded various rights and privileges to Nazranies (Saint Thomas Christians) on copper plates, known as Cheppeds, or Royal Grants or Sasanam.[14]

- Iravikorthan Sassanam, awarded by Shri Veera Raghava Perumal (in c. AD 774)

- Tharissapalli Chepped, awarded in AD 849 by the King of Venadu (Quilon), Ayyan Atikal Tiruvatikal, to Sapir Isho, the leader of Syrian Christians in Malabar Coast in the 5th regnal year of the Chera ruler Sthanu Ravi Varma. It is the first important inscription of Kerala, the date of which has been determined with accuracy.[15][16][17] It is engraved on copper plates in vatteluttu and signed by 25 witnesses. Names of fifteen of them are in Kufic, ten in Pahlavi, and four i Hebrew.

- Jewish Copper Plate, awarded by Bhaskara Ravi Varman I Perumal (962-1019 A.D.), is a Sasanam outlining the grant of rights of the Anjuvannam and 72 other properietary rights to local Jewish Chief Ousepp Irabban

Grants

One of the most important sources of history in the Indian subcontinent are the royal records of grants engraved on copper-plates (tamra-shasan or tamra-patra; tamra means copper in Sanskrit and several other Indian languages). Because copper does not rust or decay, they can survive virtually indefinitely.

Collections of archaeological texts from the copper-plates and rock-inscriptions have been compiled and published by the Archaeological Survey of India during the past century.

Approximate dimensions of copper plate is 9 3⁄4 inch long × 3 1⁄4 inch high × 1/10 (to 1/16) inch thick.

The earliest known copper-plate, known as the Sohgaura copper-plate, is a Maurya record that mentions famine relief efforts. It is one of the very few pre-Ashoka Brahmi inscriptions in India.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ N. Havalaiah (2004-01-24). "Ancient inscriptions unearthed". The Hindu, Saturday, Jan 24, 2004. Chennai, India: The Hindu. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- 1 2 Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York: Grove Press. pp. 155–157. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- ↑ "Nature and Importance of Indian Epigraphy". Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ Epigraphical lore of Tirupati published in Saptagiri magazine.

- ↑ "Nature and Importance of Indian Epigraphy - Chapter IV". Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ↑ "History and Culture of Tamil Nadu : As Gleaned from the Sanskrit Inscriptions". Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ↑ Caldwell, Robert (1875). A comparative grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages. Trübner & co. p. 88.

In southern states, every inscription of an early date and majority even of modern day inscriptions were written in Sanskrit...In the Tamil country, on the contrary, all the inscriptions belonging to an early period are written in Tamil with some Prakrit

- ↑ Dating of Indian literature is largely based on relative dating relying on internal evidences with a few anchors. I. Mahadevan’s dating of Pukalur inscription proves some of the Sangam verses. See George L. Hart, "Poems of Ancient Tamil, University of Berkeley Press, 1975, p.7-8

- ↑ George Hart, "Some Related Literary Conventions in Tamil and Indo-Aryan and Their Significance" Journal of the American Oriental Society, 94:2 (Apr - Jun 1974), pp. 157-167.

- ↑ Kamil Veith Zvelebil, Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, pp12

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. (1955). A History of South India, OUP, New Delhi (Reprinted 2002)

- ↑ "Tamil". The Language Materials Project. UCLA International Institute, UCLA. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ↑ Iravatham Mahadevan (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

- ↑ SG Pothen. Syrian Christians of Kerala (1970). p. 32-33.

- ↑ A. Sreedhara Menon. Kerala History (1999). p.54.

- ↑ N.M. Mathew History of the Marthoma Church (Malayalam), Volume I. p. 105-109.

- ↑ Cheriyan, Dr. C.V. Orthodox Christianity in India. p. 85, 126, 127, 444-447.

- ↑ Thapar, Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas,2014, pp. 10

External links

- A new facet of our history buried with the copper plate of Chodaganga

- Chiplun Copper-Plate Grant of Pulikeshin II (ca. 609-642 CE)

- A new copper-plate grant of Harsavardhana from the Punjab, year 8

- Vaisnavism in Upper Mahanadi Valley