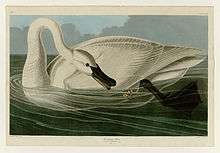

Trumpeter swan

| Trumpeter swan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Subfamily: | Anserinae |

| Tribe: | Cygnini |

| Genus: | Cygnus |

| Species: | C. buccinator |

| Binomial name | |

| Cygnus buccinator Richardson, 1832 | |

The trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator) is a species of swan found in North America. The heaviest living bird native to North America, it is also the largest extant species of waterfowl with a wingspan that may exceed 10 ft (3.0 m).[2] It is the American counterpart and a close relative of the whooper swan (Cygnus cygnus) of Eurasia, and even has been considered the same species by some authorities.[3] By 1933, fewer than 70 wild trumpeters were known to exist, and extinction seemed imminent, until aerial surveys discovered a Pacific population of several thousand trumpeters around Alaska's Copper River.[4] Careful reintroductions by wildlife agencies and the Trumpeter Swan Society gradually restored the North American wild population to over 46,000 birds by 2010.[5]

Description

_RWD2.jpg)

The trumpeter swan is the largest extant species of waterfowl. Adults usually measure 138–165 cm (4 ft 6 in–5 ft 5 in) long, though large males can exceed 180 cm (5 ft 11 in) in total length.[2][6][7][8] The weight of adult birds is typically 7–13.6 kg (15–30 lb). Possibly due to seasonal variation based on food access and variability due to age, average weights in males have been reported to range from 10.9 to 12.7 kg (24 to 28 lb) and from 9.4 to 10.3 kg (21 to 23 lb) in females.[2][9][10][11] It is one of the heaviest living birds or animals capable of flight. Alongside the mute swan (Cygnus olor), Dalmatian pelican (Pelecanus crispus) and Andean condor (Vultur gryphus), it is one of the handful to scale in excess of 10 kg (22 lb) between the sexes and one survey of wintering trumpeters found it averaged second only to the condor in mean mass.[12][13] The trumpeter swan's wingspan ranges from 185 to 250 cm (6 ft 1 in to 8 ft 2 in), with the wing chord measuring 60–68 cm (24–27 in).[2][6][7][14] The largest known male trumpeter attained a length of 183 cm (6 ft 0 in), a wingspan of 3.1 m (10 ft 2 in) and a weight of 17.2 kg (38 lb). It is the second heaviest wild waterfowl ever found, as one mute swan was found to weigh a massive 23 kg (51 lb), but it has been stated that was unclear whether this swan was still capable of flight due to its bulk.[15]

The adult trumpeter swan is all white in plumage. Like mute swans cygnets, the cygnets of the trumpeter swan have light grey plumage and pinkish legs, and gain their white plumage after about a year. As with a whooper swan, this species has upright posture and generally swims with a straight neck. The trumpeter swan has a large, wedge-shaped black bill that can, in some cases, be minimally lined with salmon-pink coloration around the mouth. The bill, measuring 10.5–12 cm (4.1–4.7 in), is up to twice the length of a Canada goose's (Branta canadensis) bill and is the largest of any waterfowl. The legs are gray-pink in color, though in some birds can appear yellowish gray to even black. The tarsus measures 10.5–12 cm (4.1–4.7 in). The mute swan, introduced to North America, is scarcely smaller. However, it can easily be distinguished by its orange bill and different physical structure (particularly the neck, which is always curved down as opposed to straight in the trumpeter). The mute swan is often found year-around in developed areas near human habitation in North America, whereas trumpeters are usually only found in pristine wetlands with minimal human disturbance, especially while breeding.[2] The tundra swan (C. columbianus) more closely resembles the trumpeter, but is significantly smaller. The neck of a male trumpeter may be twice as long as the neck of a tundra swan.[2] The tundra swan can be further distinguished by its yellow lores. However, some trumpeter swans have yellow lores; many of these individuals appear to be leucistic and have paler legs than typical trumpeters.[16] Distinguishing tundra and trumpeter swans from a distance (when size is harder to gauge) can be challenging without direct comparison but it is possible thanks to the trumpeter's obviously longer neck (the great length of which is apparent even when the swan is not standing or swimming upright) and larger, wedge-shaped bill as compared to the tundra swan.

Trumpeter swans have similar calls to whooper swans and Bewick's swans. They are loud and somewhat musical creatures, with their cry sounding similar to a trumpet, which gave the bird its name.

Range and habitat

_Summer_Range_of_Trumpeter_Swan_USFWS.png)

Beginning in 1968, repeated in 1975, and then conducted at 5-year intervals, a cooperative pan-continental survey of trumpeter swans was last conducted in 2010.[5] The survey assesses trumpeter swan abundance and productivity throughout the entire breeding ranges of the three recognized North American populations: the Pacific Coast (PCP), Rocky Mountain (RMP), and Interior (IP) populations (see Figure). From 1968 to 2010 the population has increased from 3,722 to approximately 46,225 birds, in large part due to re-introductions to its historic range.[5]

Their breeding habitat is large shallow ponds, undisturbed lakes, pristine wetlands and wide slow rivers, and marshes in northwestern and central North America, with the largest numbers of breeding pairs found in Alaska. They prefer nesting sites with enough space for them to have enough surface water for them to take off, as well as accessible food, shallow, unpolluted water, and little or no human disturbance.[17] Natural populations of these swans migrate to and from the Pacific coast and portions of the United States, flying in V-shaped flocks. Released populations are mostly non-migratory.

In the winter, they migrate to the southern tier of Canada, the eastern part of the northwest states in the United States, especially to the Red Rock Lakes area of Montana, the north Puget Sound region of northwest Washington state;[18] they have even been observed as far south as Pagosa Springs, Colorado. Historically, they ranged as far south as Texas and southern California.[19] In addition, there is a specimen in the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Cambridge, which was shot by F. B. Armstrong in 1909 at Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico.[20] Since 1992, trumpeter swans have been found in Arkansas each November – February on Magness Lake outside of Heber Springs.[21]

Non-migratory trumpeter swans have also been artificially introduced to some areas of Oregon, where they never originally occurred. Because of their natural beauty, they are suitable water fowl to attract bird watchers and other wildlife enthusiasts. Introduction of non-regional species in the Western states, for example through the Oregon Trumpeter Swan Program (OTSP), have also been met with criticism, but generally the perceived attractiveness of natural sites have priority over the original range of any given species.[22]

Diet

These birds feed while swimming, sometimes up-ending or dabbling to reach submerged food. The diet is almost entirely aquatic plants. They will eat both the leaves and stems of submerged and emergent vegetation. They will also dig into muddy substrate underwater to extract roots and tubers. In winter, they may also eat grasses and grains in fields. They will often feed at night as well as by day. Feeding activity, and the birds' weights, often peaks in the spring as they prepare for the breeding season.[23] The young feed on insects, small fish, fish eggs and small crustaceans along with plants initially, providing additional protein, changing to a vegetation-based diet over the first few months.

Breeding

Trumpeter swans often mate for life, and both parents participate in raising their young, but primarily the female incubates the eggs. Most pair bonds are formed when swans are 5 to 7 years old, although some pairs do not form until they are nearly 20 years old. "Divorces" have been known between birds, in which case the mates will be serially monogamous, with mates in differing breeding seasons. Occasionally, if his mate dies, a male trumpeter swan may not pair again for the rest of his life.[17] Most egg laying occurs between late April and May. The female lays 3–12 eggs, with 4 to 6 being average, in a mound of plant material on a small island, a beaver or muskrat lodge, or a floating platform on a clump of emergent vegetation. The same location may be used for several years and both members of the pair help build the nest.[17] The nest consists of a large, open bowl of grasses, sedges and various aquatic vegetation and have ranged in diameter from 1.2 to 3.6 m (3.9 to 11.8 ft), the latter after repeated uses.[24] The eggs average 73 millimetres (2.9 in) wide, 113.5 millimetres (4.5 in) long, and weigh about 320 grams (11.3 oz).[17] The eggs are quite possibly the largest of any flying bird alive today, in comparison they are about 20% larger in dimensions and mass than those of an Andean condor (Vultur gryphus), which attains similar average adult weights, and more than twice as heavy as those of kori bustards (Ardeotis kori).[25][26][27] The incubation period is 32 to 37 days, handled mainly by the female, although occasionally by the male as well. The young are able to swim within two days and usually are capable of feeding themselves after, at most, two weeks. The fledging stage is reached at roughly 3 to 4 months.[28] While nesting, trumpeter swans are territorial and harass other animals, including conspecifics, who enter the area of their nest.[17]

Adults go through a summer moult when they temporarily lose their flight feathers. The females become flightless shortly after the young hatch; the males go through this process about a month later when the females have completed their moult.

Mortality

In captivity, members of this species have survived to 33 years old and, in the wild, have lived to at least 24 years. Young trumpeter swans may have as little as 40% chance of survival due variously to disturbance and destruction by humans, predation, nest flooding, and starvation. In some areas, though, the breeding success rate is considerably greater and, occasionally, all cygnets may reach maturity. Mortality in adults is quite low, usually being 80–100% annually, unless they are hunted by humans.[29] Predators of trumpeter swan eggs include common raven (Corvus corax), common raccoon (Procyon lotor), wolverine (Gulo gulo), American black bear (Ursus americanus), brown bear (Ursus arctos), coyote (Canis latrans), wolves (Canis lupus), mountain lions (Puma concolor), and northern river otter (Lontra canadensis). Nest location can provide partial protection from most mammalian nest predators, especially if placed on islands or floating vegetation in deep waters. Most of the same predators will prey on young cygnets, as will common snapping turtle (Chelhydra serpentina), California gull (Larus californicus), great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and American mink (Mustela vison). Larger cygnets and, rarely, nesting adults may be ambushed by golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), bobcat (Lynx rufus), and coyote. When their eggs and young are threatened, the parents can be quite aggressive, initially displaying with head bobbing and hissing. If this is not sufficient, the adults will physically combat the predator, battering with their powerful wings and chomping down with their large bills, and have managed to kill predators equal to their own weight in confrontations.[30] Predation of adults when they are not nesting is rare, although they may possibly be hunted by golden and bald eagles as well as wolves and mountain lions, although even most of these cases are anecdotal and unproven. Photos of a bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) exceptionally attacking an adult trumpeter swan in mid-flight were taken recently, although the swan managed to survive the predation attempt.[31]

Conservation status

Near extinction and rediscovery in Alaska

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the trumpeter swan was hunted heavily, for game or meat, for the soft swanskins used in powder puffs, and for their quills and feathers. This species is also unusually sensitive to lead poisoning from ingesting lead shot while young. The Hudson's Bay Company captured thousands of swans annually with a total of 17,671 swans killed between 1853 and 1877. In 1908 Edward Preble wrote of the decline in the hunt with the number sold annually dropping from 1,312 in 1854 to 122 in 1877.[32] Sir John Richardson wrote in 1831 that the trumpeter "is the most common Swan in the interior of the fur-counties... It is to the trumpeter that the bulk of the Swan-skins imported by the Hudson's Bay Company belong."[33] By the early twentieth century breeding trumpeter swans were nearly extirpated in the United States except for a remnant population of fewer than 70 wild trumpeters in remote hot springs in or near Yellowstone National Park. Surprising news came from a 1950s aerial survey of Alaska's Copper River when several thousand trumpeters were discovered.[4] This population provided critical genetic stock to complement the tri-state (Montana/Idaho/Wyoming) population for re-introductions in other parts of the swan's historic range.

Historical range

In 1918 Grinnell wrote that trumpeter swans once bred in North America from northwestern Indiana west to Oregon in the U.S., and in Canada from James Bay to the Yukon, and they migrated as far south as Texas and southern California.[19] In 1960 Banko also placed their breeding range as far south as Nebraska, Missouri, Illinois, northwestern Indiana, but in Michigan turned this line northwards, placing a hypothetical eastern boundary up through Ontario to western Quebec and the eastern shore of James Bay.[34] In 1984, Lumsden posited that trumpeter swans may have been extirpated from eastern Canada by Indians armed with firearms prior to the arrival of European explorers and noted archaeological remains of trumpeter swans as far east as Port au Choix, Newfoundland dating to 2,000 BCE. He cited historical observer records of what must have been breeding trumpeters, such as Father Hennepin's August report of swans on the Detroit River from Lake St. Clair to Lake Erie in 1679 and Cadillac's 1701 report of summering swans (July 23 - October 8) in the same area: "There are such large numbers of swans that the rushes among which they are massed might be taken for lilies."[35] In the eastern United States the breeding range is potentially extended to North Carolina by the detailed historical report of Lawson (1701) that "Of the swans we have two sorts, the one we call Trompeters...These are the largest sort we have...when spring comes on they go the Lakes to breed" versus "The sort of Swans called Hoopers; are the least."[36]

Reintroduction

Early efforts to reintroduce this bird into other parts of its original range, and to introduce it elsewhere, have had modest success, as suitable habitats have dwindled and the released birds do not undertake migrations. More recently, the population in all three major population regions have shown sustained growth over the past thirty-year period. Data from the US Fish and Wildlife Service[37] show 400% growth in that period, with signs of increasing growth rates over time.

One impediment to the growth of the trumpeter swan population around the Great Lakes is the presence of a growing non-native Eurasian mute swan population who compete for habitat.[6][38]

Alberta

One of the largest conservation sites for the trumpeter swan is located in Lois Hole Provincial Park. It is located adjacent to the renamed Trumpeter subdivision of Edmonton, Alberta within Big Lake.

Michigan

Joe Johnson, a biologist for the W.K. Kellogg Bird Sanctuary, part of Michigan State University’s Kellogg Biological Station, obtained trumpeter swans from Alaska for re-introduction to Michigan beginning in 1986. The population has grown via continued re-introductions and organic growth to 756 birds by 2015. The native swans have benefited from removal of non-native mute swans by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources beginning in the 1960s, with a decline from 15,000 mute swans in 2010 to 8,700 in 2015.[39]

Minnesota

The trumpeter swan is listed as threatened in the state of Minnesota.[40]

Ontario

The Ontario Trumpeter Swan Restoration Group started a conservation project in 1982, using eggs collected in the wild. Live birds have also been taken from the wild. Since then, 584 birds have been released in Ontario. Despite lead poisoning in the wild from shotgun pellets, the prospects for restoration are considered good.[41]

See also

- Grande Prairie, Alberta, Canada — 'The Swan City'

- Ralph Edwards, a leading Canadian conservationist of trumpeter swans

- The Trumpet of the Swan, a 1970 children's novel by E. B. White.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Cygnus buccinator". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1988). Waterfowl: An Identification Guide to the Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-46727-6.

- ↑ Morony, J.J. Jr.; Bock, W.J.; Farrand, J., Jr. (1975). Reference list of the birds of the world. New York: American Museum of Natural History. OCLC 483451163.

- 1 2 Nora Steiner Mealy (Spring 1988). "Heard Swans Reprise". California Wild. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2015-07-04.

- 1 2 3 Deborah J. Groves (February 2012). The 2010 North American Trumpeter Swan Survey (PDF) (Report). USFWS. Retrieved 2015-07-04.

- 1 2 3 "Mute Swan". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- 1 2 Ogilvie, M. A.; Young, S. (2004). Wildfowl of the World. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84330-328-2.

- ↑ "Trumpeter Swan, Life History". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Orinthology. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- ↑ Drewien, R.C.; Bouffard, S.H. (1994). "Winter body mass and measurements of Trumpeter Swans Cygnus buccinator". Wildfowl. 45 (45): 22–32.

- ↑ Sparling, D.W., Day, D., & Klein, P. (1999). Acute toxicity and sublethal effects of white phosphorus in mute swans, Cygnus olor. Archives of environmental contamination and toxicology, 36(3), 316-322.

- ↑ James, M.L. (2000). Status of the trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator) in Alberta. Alberta Environment, Fisheries & Wildlife Management Division, Resource Status and Assessment Branch.

- ↑ Dunning, Jr., John B. (Editor). (2008). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses, 2nd Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- ↑ Greenwood, J.J.; Gregory, R.D.; Harris, S.; Morris, P A.; Yalden, D.W. (1996). "Relations between abundance, body size and species number in British birds and mammals". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 351 (1337): 265–278. doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0023.

- ↑ "Trumpeter Swan video, photos and facts". Arkive: Images of Life on Earth. Retrieved 2012-06-21.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ↑ Sibley, David. "Trumpeter Swans with yellow loral spots". Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mitchell, C. D.; Eichholz, M. W. (2010). "Trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator)". In Poole, A. The Birds of North America Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- ↑ "''...Trumpeter Swans...''". Washington State University Beach Watchers. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- 1 2 Grinnell, Joseph; Bryant, Harold Child; Storer, Tracy Irwin (1918). The Game Birds of California. University of California Press. p. 254. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ↑ Henry K. Coale (January 1915). "The Present Status of the Trumpeter Swan (Olor buccinator)". The Auk. American Ornithologists' Union. 32 (1): 88. doi:10.2307/4071616. JSTOR 4071616.

- ↑ Galiano, Amanda. "Trumpeter Swans on Magness Lake – Heber Springs". Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ↑ Ivey, Gary L., Martin J. St. Louis and Bradley D. Bales. 2000. "The Status of the Oregon Trumpeter Swan Program R. E. Shea, M.L. Linck, and H.K. Nelson (editors). Proceedings and Papers of the Trumpeter Swan Society Conference 17: 109-114.

- ↑ Squires, J. R.; Anderson, S.H. (1997). "Changes in trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator) activities from winter to spring in the greater Yellowstone area". American Midland Naturalist. 138 (1): 208–214. doi:10.2307/2426667. JSTOR 2426667.

- ↑ Slater, G. (2006). "'Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinator): a technical conservation assessment" (PDF). U.S. Forest Service.

- ↑ Rohwer, F.C.; Eisenhauer, D.I. (1989). "Egg mass and clutch size relationships in geese, eiders, and swans". Ornis Scandinavica. 20: 43–48. doi:10.2307/3676706.

- ↑ Brown, L.; Amadon, D. (1968). Eagles, hawks and falcons of the world. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Ginn, P. J.; McIlleron, W.G.; Milstein, P. le S. (1989). The Complete Book of southern African birds. Cape Town: Struik Winchester. ISBN 9780947430115.

- ↑ "Trumpeter Swan Fact Sheet". Lincoln Park Zoo. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ↑ Krementz, D.; Barker, R.; Nichols, J. (1997). "Sources of Variation in Waterfowl Survival Rates". The Auk. 114 (2): 93–102. doi:10.2307/4089068. JSTOR 4089068.

- ↑ Kraft, F. (1946). "The Flying Behemoth is Coming Back". Saturday Evening Post. 219 (6). p. 6.

- ↑ "Bald Eagle attacking a Trumpeter Swan". Utahbirds.org. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ↑ Edward Alexander Preble. "A Biological Investigation of the Athabaska-Mackenzie Region". North American Fauna. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 27: 309. doi:10.3996/nafa.27.0001. Retrieved 2015-07-05.

- ↑ William Swainson; John Richardson; William Kirby (1831). Fauna Boreali-Americana. Part 2, The Birds. London: John Murray. p. 464. Retrieved 2015-07-05.

- ↑ Winston E. Banko (April 30, 1960). "The Trumpeter Swan, Its History, Habits and Population in the United States". North American Fauna. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 63 (63): 1–214. doi:10.3996/nafa.63.0001. Retrieved 2015-07-05.

- ↑ Harry G. Lumsden (October–December 1984). "The Pre-Settlement Breeding Distribution of Trumpeter, Cygnus buccinator, and Tundra Swans, C. columbianus, in Eastern Canada". The Canadian Field-Naturalist. 98 (4). Retrieved 2015-07-05.

- ↑ John Lawson (1709). A new voyage to Carolina; containing the exact description and natural history of that country. London: John Stevens. p. 146. Retrieved 2015-07-05.

- ↑ Caithamer, David F. (February 2001). "Trumpeter Swan Population Status, 2000" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ↑ "Trumpeter Swan". Hinterland Who's Who. Environment Canada & Canadian Wildlife Federation. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22.

- ↑ Howard Meyerson (November 17, 2015). "Trumpeter Swans: A Conservation Success in Michigan". The Outdoor Journal. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ "Minnesota Endangered & Threatened Species List" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ↑ "Toronto Zoo > Conservation > Birds". Retrieved 2009-09-22.

Further reading

- Bergman, Charles A. (October 1985). "The Triumphant Trumpeter". National Geographic. Vol. 168 no. 4. pp. 544–558. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cygnus buccinator. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Cygnus buccinator |

- BirdLife species factsheet for Cygnus buccinator

- Trumpeter Swan Society home page

- Trumpeter Swan – Cygnus buccinator – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Trumpeter Swan – Alaska Department of Fish and Game

- "Trumpeter Swan media". Internet Bird Collection.

- WSU Beachwatchers – "Winter Visitors Arrive Trumpeter Swans again feeding in the fields"

- Trumpeter Swan photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Cygnus buccinator at IUCN Red List maps