Daksha yajna

In Hindu mythology, Daksha-Yajna(m) (Daksha-Yagna(m)) or Daksha-Yaga[1][2] is an important event, which is narrated in various Hindu scriptures. It refers to a yajna (sacrifice) organized by Daksha, where his daughter Sati self-immolated herself. The wrath of god Shiva, Sati's husband, thereafter destroyed the sacrifice. The tale is also called Daksha-Yajna-Nasha ("destruction of Daksha's sacrifice). The story forms the basis of the establishment of the Shakti Peethas, temples of the Hindu Divine Mother. It is also becomes a prelude to the story of Parvati, Sati's reincarnation who later marries Shiva.

The mythology is mainly told in the Vayu Purana. It is also mentioned in the Kasi Kanda of the Skanda Purana, the Kurma Purana, Harivamsa Purana and Padma Purana. Linga Purana, Shiva Purana, and Matsya Purana also detail the incident.

Background

Sati-Shiva marriage

Daksha was one of the Prajapati, son of Brahma, and among his foremost creations. The name Daksha means "skilled one". Daksha had two wives: Prasoothi and Panchajani (Virini). Sati (also known as ‘‘Uma’’) was his youngest daughter; born from Prasoothi (the daughter of the Prajapati Manu), she was the pet child of Daksha and he always carried her with him. Sati (meaning truth) is also called Dakshayani as she followed Daksha’s path; this is derived from the Sanskrit words daksha and ayana (walk or path).[3][4][5]

Sati, the youngest daughter of Daksha,[5] was deeply in love with the god Shiva and wished to become his wife. Her worship and devotion of Shiva strengthened her immense desire to become his wife. However, Daksha did not like his daughter’s yearning for Shiva, mainly because he was a Prajapati and the son of the god Brahma; his daughter Sati was a royal princess. They were wealthy nobility and their imperial royal lifestyle was entirely different from that of Shiva. As an emperor, Daksha wanted to increase his influence and power by making marriage alliances with powerful empires and influential sages and gods.[3]

Shiva on the other hand led a very modest life. He lived among the downtrodden, wore a tiger skin, smeared ashes on his body, had thick locks of matted hair, and begged with a skull as bowl. His abode was Mount Kailash in the Himalayas. He embraced all kinds of living beings and did not make any distinction between good souls and bad souls. The Bhutaganas, his followers, consisted of all kinds of ghosts, demons, ghouls and goblins. He wandered though garden and graveyard alike.[6]

As a consequence, Daksha had aversion towards Shiva being his daughter’s companion. However unlike Daksha, Sati loved Shiva as she had the revelation that Shiva was the Supreme God.[3][7]

Sati won Shiva as her husband by undergoing severe austerities (tapas). Despite Daksha's disappointment, Sati married Shiva.

Brahma's yajna

Once Brahma conducted a huge yajna (sacrifice), where all the Prajapatis, gods and kings of the world were invited. Shiva and Sati were also called on to participate in the yajna. All of them came for the yajna and sat in the ceremonial place. Daksha came last. When he arrived, everyone in the yajna, with the exception of Brahma, Shiva and Sati, stood up showing reverence for him.[8] Brahma being Daksha's father and Shiva being Daksha's son-in-law were considered superior in stature to Daksha. Daksha misunderstood Shiva’s gesture and considered Shiva's gesture as an insult. Daksha vowed to take revenge on the insult in the same manner.[5]

Ceremony

Daksha’s grudge towards Shiva grew after Brahma's yajna. With the prime motive of insulting Shiva, Daksha initiated a great yajna, similar to that of Brahma. The yajna was to be presided over by the sage Bhrigu. He invited all the gods, Prajapatis and kings to attend the yajna and intentionally avoided inviting Shiva and Sati.[5][8]

Dadhichi-Daksha argument

The Kurma Purana discusses the dialogues between the sage Dadhichi and Daksha. After the sacrifice and hymns where offered to the twelve Aditya gods; Dadhichi noticed that there was no sacrificial portion (Havvis) allotted to Shiva and his wife, and no vedic hymns were used in the yajna addressing Shiva which were part of Vedic hymns. He warned Daksha that he should not alter the Holy Vedas for personal reasons; the priests and sages supported this. Daksha replied to Dadhichi that he would not do so and insulted Shiva. Dadhichi left the yajna because of this argument.[2]

Sati's death

Sati came to know about the grand yajna organized by her father and asked Shiva to attend the yajna. Shiva refused her request, saying that it was unappropriate to attend a function without being invited. He reminded her that she was now his wife more than Daksha’s daughter and, after marriage, is a member of Shiva’s family rather than Daksha’s. The feeling of her bond to her parents overpowered the social etiquette she had to follow. She even had a notion that there was no need to have received an invitation in order to attend as she was Daksha’s favourite daughter and no formality existed between them. She constantly pleaded and urged Shiva to let her attend the ceremony, and became adamant in her demands without listening to the reasons Shiva provided for not attending the function. He allowed Sati to go to her parents' home, along with his followers including Nandi, and attend the ceremony, but refused to accompany with her.[7]

Upon arriving, Sati tried to meet her parents and sisters; Daksha was arrogant and avoided interacting with Sati. He repeatedly snubbed her in front of all the dignitaries but Sati maintained her composure. Because of Sati’s persistence in trying to meet him, Daksha reacted vehemently, insulting her in front of all the other guests at the ceremony to which she had not been invited. He called Shiva an atheist and cremation ground dweller. As planned, he took advantage of the situation and continued shouting repugnant words against Shiva. Sati felt deep remorse for not listening to her beloved husband. Daksha’s disdain towards her, and especially her husband Shiva, in front of all the guests was growing each moment she stood there. The shameless insult and humiliation of her and her beloved, eventually became too much to bear.[3][9]

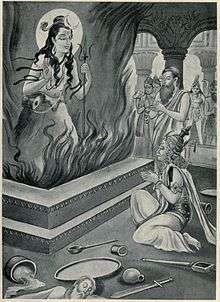

She cursed Daksha for acting so atrociously toward her and Shiva, and reminded him that his haughty behavior had blinded his intellect. She cursed him and warned that the wrath of Shiva would destroy him and his empire. Unable to bear further humiliation, Sati committed suicide by jumping into the sacrificial fire.[2][3][8] The onlookers tried to save her but it was too late.[5] They were only able to retrieve the half burnt body of Sati. Daksha's pride in being a Prajapati and his prejudice against his son-in-law created a mass hatred within himself, which resulted in the death of his daughter.[3][7]

The Nandi and the accompanying Bhootaganas left the yajna place after the incident. Nandi cursed the participants and Bhrigu reacted by cursing the Bhootaganas back.

Destruction of the yajna by Shiva

Shiva was deeply pained upon hearing of his wife's death. His grief grew into a terrible anger when he realized how Daksha had viciously plotted a treachery against him; but it was his innocent wife who fell into the trap instead of him. Shiva learned of Daksha’s callous behavior towards Sati. Shiva's rage became so intense that he plucked a lock of hair from his head and smashed it on the ground, breaking it into two with his leg. Armed and frightening, two fearsome beings Virabhadra and Bhadrakali (Rudrakali)[5] emerged. Shiva ordered them to kill Daksha and destroy the yajna.[7]

The ferocious Virabhadra and Bhadrakali, along with the Bhutaganas, reached the yajna spot. The invitees renounced the yajna and started running away from the turmoil. Sage Bhrigu created an army with his divine penance powers to resist Shiva’s attack and protect the yajna. Bhrigu’s army was demolished and the entire premises were ravaged. All those who participated, even the other Prajapatis and the gods, were mercilessly beaten, wounded or even slaughtered.[3][7] The Vayu Purana mentions the attack of Bhutaganas: the nose of some goddesses were cut, Yama's staff bone was broken, Mitra's eyes were pulled out, Indra was trampled by Virabhadra and Bhutaganas, Pushan's teeth were knocked out, Chandra was beaten heavily, all of the Prajapatis' were beaten, the hands of Vahini were cut off, and Bhrigu's beard was cut off.[2]

Daksha was caught and decapitated, the attack culminated when the Bhutaganas started plucking out Bhrigu’s white beard as a victory souvenir.[3][7] The Vayu Purana do not mention the decapitation of Daksha, instead it says Yagnja, the personification of yajna took the form of an antelope and jumped towards the sky. Virabhadra captured it and decapitated Yagnja. Daksha begs mercy from the Parabrahman (the Supreme Almighty who is formless), who rose from the yajna fire and forgives Daksha. The Parabharman informs Daksha that Shiva is in fact a manifestation of Parabrahman. Daksha then becomes a great devotee of Shiva. The Linga Purana and Bhagavatha Purana mention the decapitation of Daksha.[2]

Certain other puranas like Harivamsa, Kurma, and Skanda narrate the story from the perspective of the Vishnava-Shaiva community feud prevalent in ancient times. In these puranas, there are fights between Vishnu and Shiva or Virabhadra, with various victors throughout. The story of Daksha Yaga in Vaishnava and Shaiva puranas end with the surrendering of Daksha to the Parabrahman or with the destruction of yajna and decapitation of Daksha.[2]

Aftermath

As the obstruction of the yajna will create havoc and severe ill effects on the nature, Brahma and the god Vishnu went to the grief-stricken Shiva. They comforted and showed their sympathy towards Shiva. They requested him to come to the yajna location and pacify the bhutaganas and allow the yaga to be completed; Shiva agreed. Shiva found the burnt body of Sati. Shiva gave permission to continue yajna. Daksha was absolved by Shiva and the head of a ram (Male goat) meant for yajna was fixed on the decapitated body of Daksha and gave his life back. The yajna was completed successfully.[10]

The later story is an epilogue to the story of Daksha yajna mentioned in Shakta Puranas like Devi Bhagavata Purana, Kalika Purana and the folklores of various regions. Shiva was so distressed and could not part from his beloved wife. He took the corpse of Sati and wandered around the universe. To reduce Shiva's grief, Vishnu cuts Sati's corpse as per Vaishnava Puranas; whose parts fell on the places Shiva wandered. The Shaiva version says that her body disintegrated on its own and the parts fell while Shiva was carrying Sati's corpse in various places. These places commemorating each body part came to be known as the Shakti peethas. There are 51 Shakti peethas, representing the 51 alphabets of Sanskrit.[10] Some of the puranas which came in later ages gave more importance to their supreme deity (depending on Vaishnava, Shaiva, and Shakta sects) in their literature.[11][12]

Shiva went to isolation and solitude for ages and wandered all around until Sati reincarnated as Parvati, the daughter of the King Himavana. Like Sati, Parvati took severe austerities and gave away all her royal privileges and went to forest. Shiva tested her affection and devotion in disguise. He eventually realized Parvati is Sati herself. Shiva later on married Parvati.[3][10]

Shakti Peethas

The mythology of Daksha Yaga is considered to be the story of origin of Shakti Peethas. Shakti Peethas are sacred abodes of Devi. These shrines are located all over South Asia. Most of the temples are located in India and Bangladesh; there are a few shrines in Pakistan, Nepal and Sri Lanka. There are 51 Shakti Peethas as per the puranas denoting the 51 Sanskrit alphabets.[13] However 52, and 108 are also believed to exist. Shakti Peethas are the revered temples of the Shakta (Shaktism) sect of Hinduism. It is said that the body part of the corpse of Sati Devi fell in these places and the shrines are mostly now associated with the name of the body part. Out of the 51 Shakti peethas, 18 are said to be Maha Shakti peethas. They are: Sharada Peetham (Saraswati devi), Varanasi Peetham (Vishalakshi devi), Gaya Peetham (Sarvamangala devi), Jwalamukhi Peetham (Vaishnavi devi), Prayaga Peetham (Madhaveswari devi), Kamarupa Peetham (Kamakhyadevi), Draksharama Peetham (Manikyamba devi),[14] Oddyana Peetha (Girija Viraja devi), Pushkarini Peetham (Puruhutika devi), Ujjaini Peetham (Mahakali devi), Ekaveera Peetham (Renuka Devi),[15] Shri Peetham (Mahalakshmi devi),[16] Shrishaila Peetham (Bhramaramba devi), Yogini Peetham (Yogaamba(Jogulamba) devi),[17] Krounja Peetham (Chamundeshwari devi), Pradyumna Peetham (Shrinkala devi),[18] Kanchi Kamakodi Peetham (Kamakshi devi), and Lanka Peetham (Shankari devi).[19]

Commemoration

Various sites like Kottiyoor, Kerala; the Daksheswara Mahadev Temple of Kankhal in Uttarakhand, and Draksharama, in Andhra Pradesh claim to be the location of Daksha yajna and the self-immolation of Sati.

Kottiyoor Vysakha Mahotsavam, a 27‑day yagnja ceremony, conducted in the serene hilly jungle location of Kottiyoor yearly commemorating the Daksha Yaga. The pooja and rituals were classified by Shri Sankaracharya.[20]

References

- ↑ http://www.kamakoti.org/kamakoti/details/shivapuranam12.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Vaayu Purana". Horace Hayman Wilson. pp. 62–69. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ramesh Menon (2011). Siva: The Siva Purana Retold (1, Fourth Re-print ed.). Rupa and Co. ISBN 812911495X.

- ↑ "The list of Hindu sacred books". John Bruno Hare. 2010. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Skanda Purana (Pre-historic Sanskrtit literature), G. V. TAGARE (Author), (August 1, 1992). G.P. Bhatt, ed. Skanda-Purana, Part 1. Ganesh Vasudeo Tagare (trans.) (1 ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 8120809661.

- ↑ "If one is hurt by the arrows of an enemy, one is not as aggrieved as when cut by the unkind words of a relative, for such grief continues to rend one's heart day and night". Naturallyyoga.com. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Essence Of Maha Bhagavatha Purana". Shri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- 1 2 3 "ഇതു ദക്ഷ യാഗ ഭൂമി". Malayala Manorama. 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ↑ "Lord Shiva stories, Shiva purana". Sivaporana.blogspot.in. 2009. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- 1 2 3 (Translator), Swami Vijnanananda (2007). The Srimad Devi Bhagavatam. Munshiram Maniharlal. ISBN 8121505917.

- ↑ "What are Puranas? Are they Myths?". boloji.com. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ Wendy Doniger, ed. (1993). Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791413814.

- ↑ Roger Housden (1996). Travels Through Sacred India (1 ed.). Thorsons. ISBN 1855384973.

- ↑ "Manikyamba devi, Draksharamam (Andhra Pradesh)". specialyatra.com. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ "18 Shakti peethas". shaktipeethas.org. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ "Mahalakshmi Temple Kolapur". mahalaxmikolhapur.com. 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ "Jogulamba Temple, Alampur". hoparoundindia.com. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ "Travel Guru: Ashta Dasha Shakti Peethas (Shankari devi, Kamakshi Devi, Srigala Devi, Chamundeshwari devi, Jogulamba devi, Bhramaramba devi, Mahalakshmi devi, Ekaveerika Devi, Mahakali devi, Puruhutika devi, Girija Devi, Manikyamba devi, Kamarupa devi, Madhaveswari devi, Vaishnavi devi, Sarvamangala devi, Vishalakshi devi, Saraswathi devi)". Badatravelguru.blogspot.in. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ↑ E. Alan Morinis (1984). Pilgrimage in the Hindu Tradition: A Case Study of West Bengal. US: Oxford University South Asian studies series, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195614127.

- ↑ Kottiyoor/ "Sri Kottiyoor" Check

|url=value (help). Sri Kottiyoor. 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.