Day of Rage (Bahrain)

| Day of Rage | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Bahraini uprising (2011–present) | |||

|

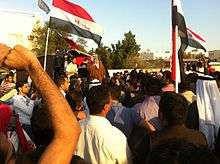

Protesters fleeing after security forces fired tear gas on a march in Nuwaidrat. | |||

| Date | 14 February 2011 | ||

| Location |

26°01′39″N 50°33′00″E / 26.02750°N 50.55000°ECoordinates: 26°01′39″N 50°33′00″E / 26.02750°N 50.55000°E | ||

| Causes | Alleged discrimination against Shias,[1] unemployment, slow pace of democratisation and Inspiration from concurrent regional protests.[1] | ||

| Goals | Constitutional monarchy, rewrite the Constitution,[2]:67 resignation of the prime minister[3] and an end to alleged economic and human rights violations.[1] | ||

| Methods | Civil resistance and Demonstrations | ||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| |||

Day of Rage (Arabic: يوم الغضب) is the name given by protesters in Bahrain to 14 February 2011, the first day of their national uprising. Inspired by the successful uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia, Bahraini youth organised protests using social media websites. They appealed to the Bahraini people "to take to the streets on Monday 14 February in a peaceful and orderly manner." The day had a symbolic value being the ninth and tenth anniversaries of the Constitution of 2002 and the National Action Charter respectively.

Some opposition parties supported the protests' plans, while others did not explicitly call for demonstration. However, they demanded deep reforms and changes similar to those by the youth. Before the start of protests, the government introduced a number of economic and political concessions. The protests started with a sit-in in solidarity with the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 in the vicinity of the Egyptian embassy in the capital, Manama ten days before the 'Day of Rage'. On the eve of 14 February, security forces dispersed hundreds of protesters south of Manama.

On 14 February, thousands of Bahrainis participated in 55 marches in 25 locations throughout Bahrain. Protests were peaceful and protesters demanded deep reforms. The earliest demonstration started at 5:30 a.m. in Nuwaidrat, the last just minutes before midnight in the vicinity of Salmaniya hospital heading to the Pearl Roundabout. The largest was in Sitra island. Security forces responded to protests by firing tear gas, rubber bullets, stun grenades and birdshot. More than 30 protesters were injured and one was killed by birdshot. The Bahraini Ministry of Interior said a number of security forces were injured after groups of protesters attacked them.

Background

Bahrain is a tiny island in the Persian Gulf that hosts the United States Naval Support Activity Bahrain, the home of the US Fifth Fleet; the US Department of Defense considers the location critical for its ability to counter Iranian military power in the region.[7] The Saudi Arabian government and other Gulf region governments strongly support the King of Bahrain.[8] Although government officials and media often accuse the opposition of being influenced by Iran, a government-appointed commission found no evidence supporting the claim.[9] Iran has historically claimed Bahrain as a province,[10] but the claim was dropped after a UN 1970 survey found that most Bahraini people preferred independence over Iranian control.[11]

Modern political history

Bahrainis have protested sporadically throughout the last decades demanding social, economic and political reforms.[2]:162 In the 1950s, following sectarian clashes, the National Union Committee was formed by reformists; it demanded an elected popular assembly and carried out protests and general strikes. In 1965 a month-long uprising broke out after hundreds of workers at Bahrain Petroleum Company were laid off. Bahrain became independent from Britain in 1971 and the country had its first parliamentary election in 1973. Two years later, the government proposed a law called the "State Security Law" giving police wide arresting powers and allowing individuals to be held in prison without trial for up to three years. The assembly rejected the law, prompting the late Amir to dissolve it and suspend the constitution. It was not until 2002 that Bahrain held any parliamentary elections, after protests and violence between 1994 and 2001.[12][13][14]

Economy

Despite its oil-rich Gulf neighbors, Bahrain's oil, discovered in 1932,[15] has "virtually dried up" making it poorer than other countries in its region.[16] In recent decades, Bahrain has moved towards banking and tourism[17] making it one of the most important financial hubs in the region; it has since held some of the top international rankings in economic freedom[18] and business-friendly countries,[19] making it the freest economy in the Middle East.[20] However, Bahrainis suffer from relative poverty.[21] Semi-official studies found that the poverty threshold (the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a given country.[22]) in the country in 1995 was .د.ب 308. The Bahrain Centre for Human Rights said that by 2007 it had increased to .د.ب 400 at least,[23] putting half of Bahrainis under the poverty line.[24] In 2008, the government rejected the UN's conclusion that 2% of Bahrainis lived in "slum-like conditions".[25] Poor families receive monthly financial support.[26] In 2007, CNN produced a documentary titled "Poverty in Bahrain",[27][28] which was criticized by pro-government newspaper, Gulf Daily News.[29] Al Jazeera produced a similar documentary in 2010.[30]

The unemployment rate in Bahrain is among the highest in GCC countries.[31] Sources close to the government estimated it between 3.7%[32] and 5.4%,[33] while other sources said it was as high as 15%.[34][35] Unemployed was especially widespread among youth[34] and the Shia community.[2]:35 Bahrain also suffers from a "housing problem"[36] with the number of housing applications reaching about 53,000 in 2010.[37] These conditions prompted the Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights to consider housing one of the most important problems in Bahrain.[38]

Human rights

Human rights in Bahrain improved after the government introduced reform plans in 1999–2002 but declined again in subsequent years. Between 2007 and 2011 Bahrain's international rankings fell 21 places from number 123 to 144 on the Democracy Index, as ranked by the Economist Intelligence Unit.[39][40] The Freedom in the World index on political freedom classified Bahrain as "Not Free" in 2010–2011.[41] A Freedom House "Freedom on the Net" survey classified "Net status" as "Not free" and noted that more than 1,000 websites were blocked in Bahrain.[42]:1 The Press Freedom Index (by Reporters Without Borders) declined significantly: in 2002 Bahrain was ranked number 67[43] and by 2010 it had fallen to number 144.[44] The Freedom of the Press report (by Freedom House) classified Bahrain in 2011 as "Not Free".[45] Human Rights Watch has described Bahrain's record on human rights as "dismal", and having "deteriorated sharply in the latter half of 2010".[46]

Torture

During the period between 1975 and 1999 known as the "State Security Law Era", the Bahraini government frequently used torture, which resulted in a number of deaths.[47][48] After the Emir Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa succeeded his father Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa in 1999, reports of torture declined dramatically and conditions of detention improved.[49] However Royal Decree 56 of 2002 gave effective immunity to all those accused of torture during the uprising in the 1990s and before (including notorious figures such as Ian Henderson[50] and Adel Flaifel.[51]). Towards the end of 2007 the government began employing torture again and by 2010 its use had become common again.[52]

Shia grievances

The Shia majority ruled by the Sunni Al khalifa family since the eighteenth century have long complained of what they call systemic discrimination.[53] They are blocked from serving in important political and military posts[54][55] and the government has reportedly naturalized Sunnis originally from Pakistan and Syria in what Shia say is an attempt to increase the percentage of Sunnis in the population.[56][57]

According to Khalil al-Marzooq of Al Wefaq, the number of those granted Bahraini nationality between 2001 and 2008 is 68 thousand.[58] According to al-Marzooq, this number was calculated using official estimates by subtracting the population in 2001 (405,000) and natural increase (65,000) from the population in 2008 (537,000).[58] In a rally against "political naturalization", Sunni opposition activist Ibrahim Sharif estimated that 100,000 were naturalized by 2010 and thus comprised 20% of Bahraini citizens.[59] The government rejected accusations of undertaking any "sectarian naturalization policy".[57] Shia grievances were exacerbated when in 2006 Salah Al Bandar, then an adviser to the Cabinet Affairs Ministry, revealed an alleged political conspiracy aiming to disenfranchise and marginalize Shias, who comprise about 60% of the population.[60]

2010 crackdown

In August 2010, authorities launched a two-month-long crackdown, referred to as the Manama incident, arresting hundreds of opposition activists, most of whom were members of the Shia organizations Haq Movement and Al Wafa' Islamic party, in addition to human rights activists.[61] The arrestees were accused of forming a "terrorist network" aiming to overthrow the government.[62] However, a month later Al Wefaq opposition party, which was not targeted by the crackdown, won a plurality in the parliamentary election.[61][62]

Calls for a revolution

Inspired by the successful uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia,[1] opposition activists began in January to post on a large scale to the social media websites Facebook and Twitter and online forums, and to send e-mails and text messages with calls to stage major pro-democracy protests.[2]:65[53][63] The Bahraini government blocked a Facebook page which had 14,000 "likes" calling for a revolution and a "day of rage" on 14 February;[53][64] however the "likes" had risen to 22,000 few days later.[65] Another online group called "The Youth of the February 14th Revolution" described itself as "unaffiliated with any political movement or organisation" and rejected any "religious, sectarian or ideological bases" for their demands. They issued a statement listing a number of demands and steps it said were unavoidable in order to achieve "change and radical reforms".[2]:65

Bahraini youths described their plans as an appeal for Bahrainis "to take to the streets on Monday 14 February in a peaceful and orderly manner in order to rewrite the constitution and to establish a body with a full popular mandate to investigate and hold to account economic, political and social violations, including stolen public wealth, political naturalisation, arrests, torture and other oppressive security measures, [and] institutional and economic corruption."[13] One of the main demands was resignation of the king's uncle, Prince Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa from his post as prime minister.[3] He had been the unelected prime minister of Bahrain since 1971, making him the world's longest serving prime minister.[66]

The day had a symbolic value;[53] it was the tenth anniversary of a referendum in favor of the National Action Charter which had promised to introduce democratic reforms following the 1990s uprising. It was also the ninth anniversary of the Constitution of 2002, which had made opposition feel "betrayed" by the king.[67] The Constitution had brought some promised reforms, such as an elected parliament; however opposition activists said it went back on reform plans, giving the king the power to appoint half the parliamentary seats and withholding power from parliament to elect the prime minister.[2]:67

Unregistered opposition parties such as Haq Movement and Bahrain Freedom Movement supported the plans. The National Democratic Action Society only announced a day before the protests that it supported "the principle of the right of the youth to demonstrate peacefully". Other opposition groups including Al Wefaq, Bahrain's main opposition party, did not explicitly call for or support protests; however Al Wefaq leader Ali Salman did demand political reforms.[2]:66

Events leading to the protests

A few weeks before the protests, the Cabinet of Bahrain made a number of concessions, including increasing social spending and offering to free some of the minors arrested in the Manama incident in August.[68] On 4 February, several hundred Bahrainis gathered in front of the Egyptian embassy in Manama to express support for anti-government protesters there.[69] According to The Wall Street Journal, this was "one of the first such gatherings to be held in the oil-rich Persian Gulf states."[69] At the gathering, Ibrahim Sharif, the secretary-general of the National Democratic Action Society (Wa'ad), called for "local reform."[69]

On 11 February, hundreds of Bahrainis and Egyptians took to the streets near the Egyptian embassy in Manama to celebrate the fall of Egypt's president Hosni Mubarak following the successful Egyptian Revolution of 2011. Security forces reacted swiftly to contain the crowd by setting a number of roadblocks.[53] In the Khutbah preceding Friday prayer, Shiekh Isa Qassim, a leading Shia cleric, said "the winds of change in the Arab world [are] unstoppable". He demanded an end to torture and discrimination, the release of political activists and a rewriting of the constitution.[2]:67

Appearing on the state media, king Hamad announced that each family would be given 1,000 Bahraini Dinars ($2,650) to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the National Action Charter referendum. Agence France-Presse linked payments to the 14 February demonstration plans.[70]

The next day, the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights sent an open letter to the king urging him to avoid a "worst-case scenario" by introducing a wide range of reforms, including "releasing more than 450 detainees including [Bahraini] human rights defenders, religious figures and more than 110 children, dissolv[ing] the security apparatus and prosecut[ing] its official[s] responsible [for] violations".[53][71][72] At night, residents of Jidhafs held a public dinner banquet to celebrate the fall of Egypt's president.[73]

On 13 February, authorities set up a number of checkpoints and increased the presence of security forces in key locations such as shopping malls.[53] Al Jazeera interpreted the move as "a clear warning against holding Monday's [14 February] rally".[53] At night, police fired tear gas and rubber bullets on a small group of youth who organized a protest in Karzakan after a wedding ceremony. According to a photographer working for the Associated Press, several people were injured and others suffered from the effects of tear gas.[53] Bahrain's Ministry of Interior said that about 100 individuals who gathered in an unauthorized rally in the village attacked security forces injuring three policemen and in response police fired two rubber bullets, one of which rebounded from the ground, injuring a protester.[6] Small protests and clashes occurred in other locations as well, such as Sabah Al Salem, Sitra, Bani Jamra and Tashan, leading to minor injuries among both protesters and security forces.[2]:68

14 February

.jpg)

Over 6,000 people participated in 55[2]:68–9, 70 demonstrations and political rallies in 25 different locations throughout Bahrain.[5] Helicopters hovered over areas where marches were due to take place[1] and the presence of security forces was heavy in a number of key locations such as the Central Business District, shopping malls and Bab Al Bahrain. The traffic directorate closed a number of roads such as those leading to Pearl Roundabout, Dana mall, Al Daih and parts of Budaiya highway in order to anticipate any non-permitted protests. Throughout the day and especially in the evening, Internet speed was much slower than usual.[5] According to Bikya Masr blog, "many people" linked this to government attempts to contain the protests.[74]

The demonstrators demanded the release of detained protesters, socio-economic and political reforms and constitutional monarchy. Protesters sought no permits, although it is required by Bahraini law.[1][2]:68–9 The Bahraini newspaper Al Wasat reported that protests were peaceful and that demonstrators did not throw stones at security forces or burn tires in streets as they used to in the previous protests.[5]

The earliest demonstration was recorded at 05:30 in the mainly Shia village of Nuwaidrat, where 300 people are said to have participated.[2]:68–9 The rally was led by Shia political activist Abdulwahhab Hussain.[75] Police dispersed this rally, resulting in some injuries, and the hospitalization of one demonstrator. Police continued to disperse rallies throughout the day with tear gas, rubber bullets, and shotguns, causing additional injuries, and hospitalizing three more demonstrators.[2]:68

One major demonstration took place in the Shi'a island of Sitra, where several thousand men, women, and children took to the streets. According to witnesses interviewed by Physicians for Human Rights, hundreds of fully armed riot police arrived on the scene and immediately began firing tear gas and sound grenades into the crowds. They then fired rubber bullets into the unarmed crowd, aiming at people in the front line who had sat down in the street in protest.[4]

In Sanabis, security forces fled the location after protesters approached them, leaving one of their vehicles behind. Protesters attached the flag of Bahrain to the vehicle instead of damaging or burning it. In Sehla, hundreds held maghrib prayer in the streets after staging a march. In Bilad Al Qadeem, protesters held a sit-in at afternoon and started marching at evening, after which security forces intervened to disperse them. In Karzakan, protesters staged a march that was joined by another march starting in Dumistan and ended peacefully.[5] In Duraz security forces fired tear gas on 100 protesters, breaking up their rally.[76]

On its Twitter account, the Ministry of Interior said that six masked individuals participating in a march in Jidhafs attacked security forces. They wrote that police responded, injuring the legs and back of one of the attackers.[5]

Casualties

In the evening of 14 February, Ali Mushaima died from police shotgun wounds to his back at close range. The government says that Ali was part of a group of 800 protesters that attacked eight policemen with rocks and metal rods. The government asserts that the police exhausted their supply of tear gas and rubber bullets in a failed attempt to disperse the crowd, and resorted to the use of shotguns. Witnesses say that there were no demonstrations at the time Ali was shot. They say Ali was seen walking with a group of officers who were pointing their guns at him. As Ali walked away, he was shot in the back by one of the officers.[2]:69, 229 The Ministry of Interior expressed its regret at the incident and announced that the death would be investigated.[1]

Later, several hundred demonstrators congregated in the car park of the hospital where Ali was taken. They staged a protest outside the hospital heading to the Pearl Roundabout; meanwhile another march was heading to the same location from King Faisal Highway. Security forces intervened, injuring some protesters and arresting 24.[2]:69 By the end of the day, more than 30 protesters had been injured, mostly by birdshot and rubber bullets.[5]

Aftermath

The following day another man, Fadhel Al-Matrook, was killed by police during the funeral of Mushaima.[77] Protesters then marched and occupied the Pearl Roundabout without police interference.[2]:71 Thousands continued camping at the site for another day.[78] On 17 February, in what became known as Bloody Thursday,[79][80][81] authorities launched a pre-dawn raid and cleared the site, killing four protesters and injuring hundreds.[2]:230–2[82][83] Protesters took refuge in Salmaniya Medical Complex where many of them demanded the fall of the regime.[84][85][86] Defying the government ban on gatherings,[87] on the evening of 18 February, hundreds of protesters marched toward the Pearl Roundabout, now under the control of the army.[88] When protesters neared the site, the army opened fire, killing Abdulredha Buhmaid and injuring dozens of others.[89][90]

Troops withdrew from the Pearl Roundabout on 19 February, and protesters reestablished their camps there.[91][92] The crown prince assured protesters that they would be allowed to camp at the roundabout and that he would lead a national dialogue.[2]:83 Protests involving up to one-fifth of the population continued over the next month[93][94][95] until the government called in Gulf Cooperation Council troops and police and declared a three-month state of emergency.[96] Despite the police crackdown that followed,[97][98] smaller-scale protests and clashes continued, mostly outside Manama's business districts.[99][100] By April 2012, more than 80 people had died during the uprising.[101] As of December 2012, protests are ongoing.[102]

Local and international reactions

In a rare national TV address on Tuesday, February 15, King Hamad expressed regret, offered his "deep condolences" to the families of those killed and announced a ministerial probe into the events.[103] He also promised reforms including a reduction in government restrictions of the Internet and other media.[3] In reference to the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, Hussain al-Rumeihy, a member of Parliament, said on 15 February it was wrong for protesters to copy the events of other Arab countries, because the situation in Bahrain is different.[104] The following day, Prime minister Khalifa ibn Salman Al Khalifa praised the king's speech and shared his regret and condolences.[105]

On the other hand, Al Wefaq, the country's largest opposition party suspended their participation in the Parliament on 15 February and threatened to resign, in protest of what it called "the brutal practices of security forces".[106] The same day, other opposition parties protested what they called the government's "excessive" reaction to protests, and the Progressive Democratic Tribune called for formation of a national body to unite Shia and Sunna like the National Union Committee had done in the 1950s.[104] The Bahrain Human Rights Society criticized the government response to protests of 14th and 15th, accusing it of censorship and non-compliance with international covenants that it had signed.[104]

Internationally, Navi Pillay, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on 15 February, called the government of Bahrain to stop what she called "the excessive use of force" against protesters and to release protest-related prisoners.[107] United States State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley said that the US was "very concerned by recent violence surrounding protests" of the 14th and 15th.[3] In a 15 February appeal, Amnesty International called the Bahraini authorities to stop using what it called "excessive force" against protesters, to put all security forces' members who had used excessive force on trial and "to respect and protect the right of freedom expression, movement and assembly in Bahrain".[77]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Bahrain activists in 'Day of Rage'". Al Jazeera English. 14 February 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Report of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (PDF) (Report). Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry. 23 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Staff Writer (16 February 2011). "U.S. concerned by violence in Bahrain protests". MSNBC. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- 1 2 Do No Harm: A Call for Bahrain to End Systematic Attacks on Doctors and Patients (PDF) (Report). Physicians for Human Rights. April 2011. p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 (Arabic) "قتيل وأكثر من 30 مصاباً في مسيرات احتجاجية أمس". Al Wasat. 15 February 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- 1 2 (Arabic) "«الداخلية»: مسيرة غير مرخصة بكرزكان وإصابة أحد المواطنين". Al Wasat. 14 February 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ Brad Knickerbocker (19 February 2011). "US faces difficult situation in Bahrain, home to US Fifth Fleet". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ Shrivastava, Sanskar (15 March 2011). "Saudi Arabian Troops Enter Bahrain, Bahrain Opposition Calls It War". The World Reporter. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Staff writer (10 November 2011). "Human Rights in Bahrain, a Casualty of Obama's Double-Standard". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ Adrian Blomfield "Bahrain hints at Iranian involvement in plot to overthrow government", The Telegraph, 6 September 2011

- ↑ Kenneth Katzman (21 March 2011). "Bahrain: Reform, Security, and U.S. Policy". Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 2 July 2012

- ↑ Adam Curtis (11 May 2012). "If you take my advice - I'd repress them". BBC News. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- 1 2 Stephen Zunes (2 March 2011). "America Blows It on Bahrain". Foreign Policy In Focus. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain: A Human Rights Crisis". Amnesty International. 26 September 1995. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain: Discovery of Oil". January 1993. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Down to the wire in Bahrain: Last chance for real political reform (Report). European Parliament. December 2012. p. 14. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ "Bahrain's economy praised for diversity and sustainability". Bahrain Economic Development Board. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ↑ 2011 Index of Economic Freedom "Ranking the Countries", 2011 Index of Economic Freedom , 2011

- ↑ The World Bank "Ease of doing business index (1=most business-friendly regulations)", The World Bank, 2010

- ↑ "Bahrain". The Heritage Foundation. The Wall Street Journal. 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Ravallion, Martin Poverty freak: A Guide to Concepts and Methods. Living Standards Measurement Papers, The World Bank, 1992, p. 25

- ↑ "Bahrain: a Heaven for Investors and the Wealthy, while workers suffer poverty and discrimination". Bahrain Centre for Human Rights. June 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Half of Bahraini Citizens are Suffering from Poverty and Poor Living Conditions". Bahrain Centre for Human Rights. 24 September 2004. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain slams poverty report". Gulf Daily News. 2 June 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain addresses relative poverty". Bahrain News Agency. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Poverty in Bahrain: CNN Report". Bahrain Centre for Human Rights. June 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ Poverty in Bahrain (YouTube). Bahrain: CNN. 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Anwar Abdulrahman (3 June 2007). "CNN ... why?". Gulf Daily News. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ (Arabic) "الفقر في البحرين". Al Jazeera. 17 May 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Elizabeth Broomhall (7 July 2011). "Bahrain and Oman have highest Gulf unemployment rates". Arabian Business. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Habib Toumi (16 March 2010). "Bahrain's unemployment rate down to 3.7 per cent". Gulf News. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "Statistics reveal dwindling unemployment in Bahrain". Bahrain News Agency. 25 March 2006. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- 1 2 MENA: The Great Job Rush (Report). Al Masah Capital. 3 July 2011. p. 12.

- ↑ "Unemployment rate". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "Minister of housing hopes to resolve housing problem in the Kingdom". Bahrain News Agency. 27 February 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain's housing scene 'set to worsen'". Trade Arabia. 4 August 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Urgent Letter: Habitat International Coalition". Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights. 3 July 2007. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "The Economist Intelligence Unit's index of democracy" (PDF). The Economist. 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ "Democracy Index 2011: Bahrain still an Authoritarian Regime, with worse rank than last year". Bahrain Centre for Human Rights. 4 December 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ Staff writer (2011). "Freedom in Bahrain 2011". Freedom House. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ Freedom of the Net 2011 - Bahrain part (PDF) (Report). Freedom House. 2011.

- ↑ Staff writer (2002). "RWB Press Freedom Index 2002". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ Staff writer (2010). "RWB Press Freedom Index 2010". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ Staff writer (2011). "FH Press Freedom Index 2011". Freedom House. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ "World Report 2011: Bahrain". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Staff writer (27 September 1995). "Bahrain Sa'id 'Abd al-Rasul al-Iskafi". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ Staff writer (1 June 1997). "Routine abuse, routine denial". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ US Department of State, Bahrain Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 2001, and Working group on arbitrary detention, para 90.

- ↑ Jon Silverman (16 April 2003). "Is the UK facing up to Bahrain's past?". BBC. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ Staff writer (16 December 2002). "Bahrain: Investigate Torture Claims Against Ex-Officer". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ "Torture Redux: The Revival of Physical Coercion during Interrogations in Bahrain". Human Rights Watch. 8 February 2010. ISBN 1-56432-597-0. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Bahrain opposition calls for rally". Al Jazeera English. 13 February 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ↑ Saeed Tayseer B Alkhunaizi (1 November 2012). "The Roots of The Bahraini Unrest". Modern Discussion. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ "Bahraini Shiites clamor for police and military jobs". Bahrain Centre for Human Rights. Associated Press. 9 November 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ (registration required) "Bahrain Gets Tough". Financial Times. 17 February 2011.

- 1 2 Andrew Hammond (4 April 2012). "Sunnis seek own voice in Bahrain's turmoil". Reuters. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- 1 2 المرزوق: تجنيس 68 ألفا خلال 7 سنوات (in Arabic). Al Wasat. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "الجمعيات الست" والمواطنون يهتفون: "بسنا تجنيس" (in Arabic). Al Wasat. 2 June 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ Lauren Frayer (2 October 2006). "Al-Bandar Ejection Exposes Bahrain Split". The Washington Post. The Associated Press. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- 1 2 Do No Harm: A Call for Bahrain to End Systematic Attacks on Doctors and Patients (PDF) (Report). Physicians for Human Rights. April 2011. p. 35.

- 1 2 Mahjoub, Taieb (October 24, 2010). "Shiites make slender gain in Bahrain election". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ "Calls for weekend protests in Syria". Al Jazeera English. 4 February 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ↑ "BAHRAIN: Authorities crack down on dissent on the Web, rights group says". Los Angeles Times. 6 February 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ "Two killed as more Bahrain protests called". Al-Ahram. Agence France-Presse. 15 February 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Robert Mackey (9 July 2012). "Bahrain Jails Rights Activist for Tweet". New York Times. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ↑ Jane Kinninmont (28 February 2011). "Bahrain's Re-Reform Movement". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain doles out money to families". Al Jazeera English. 12 February 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 Malas, Nour; Hafidh, Hassan; Millman, Joel (5 February 2011). "Protests Emerge in Jordan, Bahrain". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ↑ Staff writer (11 February 2011). "Bahrain's King Gifts $3,000 to Every Family". Agence France-Presse (via France 24). Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ↑ Press release (12 February 2011). "An Open Letter to the King of Bahrain To Avoid the Worst Case Scenario". Bahrain Centre for Human Rights. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ↑ Carey, Glen (13 February 2011). "Bahrain Human-Rights Organization Urges King to Free Detainees". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ↑ Mohamed al-Jidhafsi (13 February 2011). (Arabic) "أهالي جدحفص يقيمون مأدبة عشاء بمناسبة سقوط النظام بمصر". Al Wasat. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ Suzanne Choney. "Bahrain Internet service starting to slow". MSNBC. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ (Arabic) "عبدالوهاب حسين ..رجل وقيام ثورة". Islam Times. 9 February 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Frederik Richter (14 February 2011). "Protester killed in Bahrain "Day of Rage": witnesses". Reuters. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- 1 2 Staff Writer (15 February 2011). "Two died as protesters are violently repressed". Amnesty International. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ↑ "Bahrain Protesters Hold Ground". Al Jazeera. 16 February 2011. Archived from the original on 16 February 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ خميس البحرين الدامي. Al-Wasat (in Arabic). 18 February 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ Hani Al-Fardan (19 February 2011). ماذا بعد الخميس الدامي؟ (in Arabic). Manama Voice. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ الرصاص الحي يخترق رأس شاب وصدر آخر. Al Wasat (in Arabic). 19 February 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain Protests: Police Break Up Pearl Square Crowd". BBC News. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ شهود عيان: هجموا علينا ونحن نائمون وداسوا بأرجلهم أجسادنا. Al-Wasat (in Arabic). 18 February 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ Martin Chulov (17 February 2011). "Bahrain protests: Four killed as riot police storm Pearl Square". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ↑ Health Services Paralyzed: Bahrain’s Military Crackdown on Patients (PDF) (Report). Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières). 7 April 2011. p. 2.

- ↑ Martin Chulov (17 February 2011). "Bahrain's quiet anger turns to rage". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ↑ "More Blood In Bahrain As Troops Fire On Protesters". NPR. 18 February 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ Michael Slackman and Nadim Audi (18 February 2011). "Security Forces in Bahrain Open Fire on Protesters". New York Times. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain troops 'fire on crowds'". BBC News. 18 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-07-28. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ May Ying Welsh and Tuki Laumea (2011). Bahrain: Shouting in the Dark. Bahrain: Al Jazeera English. Event occurs at 8:30. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

In intensive care, a man named Abdulredha was clinging to life. Doctors struggled to stop his bleeding. 'This is a bullet, gunshot wound, direct to his head and he's bleeding profusely from his nose, from his ear, his brain is shattered into pieces. I don't know the name of the patient, I don't care about the name of the patient; they are all patients here.' Redha's brain was destroyed, but his body was still alive. The team rushed him to surgery.

- ↑ Staff writer (20 February 2011). "Protesters Back in Bahrain Centre – Anti-Government Protesters Reoccupy Pearl Roundabout after Troops and Police Withdraw from Protest Site in Capital". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Staff writer (19 February 2011). "Day of Transformation in Bahrain's 'Sacred Square'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Slackman, Michael (22 February 2011). "Bahraini Protesters' Calls for Unity Belie Divisions". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ↑ Staff (22 February 2011). "Bahrain King Orders Release of Political Prisoners". The Independent. UK. Associated Press. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Michael Slackman (25 February 2012). "Protesters in Bahrain Demand More Changes". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ↑ Staff writer (15 March 2011). "Bahrain King Declares State of Emergency after Protests". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Law, Bill (6 April 2011). "Police Brutality Turns Bahrain Into 'Island of Fear'. Crossing Continents (via BBC News). Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Cockburn, Patrick (18 March 2011). "The Footage That Reveals the Brutal Truth About Bahrain's Crackdown – Seven Protest Leaders Arrested as Video Clip Highlights Regime's Ruthless Grip on Power". The Independent. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Staff writer (25 January 2012). "Bahrain live blog 25 Jan 2012". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ↑ Staff writer (15 February 2012). "Heavy police presence blocks Bahrain protests". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ↑ Gregg Carlstrom (23 April 2012). "Bahrain court delays ruling in activists case". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ↑ "Bahrain Shiite majority demands transitional government". Russia Today. 23 December 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ Staff Writer (15 February 2011). "Bahrain protests: King announces probe into two deaths". BBC. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 Staff Writer (16 February 2011). "قتيل ثان في الاحتجاجات و"الوفاق" تعلق نشاطها البرلماني... ومتظاهرون يحتشدون في دوار اللؤلؤة". Al Wasat newspaper. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Staff writer (16 February 2011). "رئيس الوزراء يأسف لوفاة اثنين من أبناء البحرين". Al Wasat newspaper. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Staff Writer (16 February 2011). "أميركا "قلقة جدا" للعنف بالبحرين". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ↑ المفوضة العليا للأمم المتحدة تدعو السلطات البحرينية للتخلي عن القوة. Al Wasat (in Arabic). AFP. 16 February 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2013.