Disintegration (The Cure album)

| Disintegration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by The Cure | ||||

| Released | 2 May 1989[1][2] | |||

| Recorded | November 1988 – February 1989 | |||

| Studio | Hookend Recording Studios, Checkendon, Oxfordshire, England | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 71:47 | |||

| Label | Fiction | |||

| Producer | ||||

| The Cure chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Disintegration | ||||

|

||||

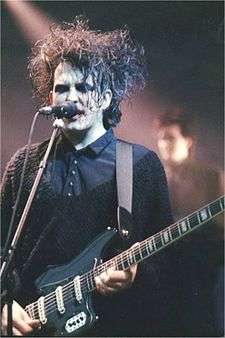

Disintegration is the eighth studio album by British alternative rock band The Cure, released on 2 May 1989 by Fiction Records. The record marks a return to the introspective and gloomy gothic rock style the band had established in the early 1980s. As he neared the age of thirty, vocalist and guitarist Robert Smith had felt an increased pressure to follow up on the group's pop successes with a more enduring work. This, coupled with a distaste for the group's newfound popularity, caused Smith to lapse back into the use of hallucinogenic drugs, the effects of which had a strong influence on the production of the album. The Cure recorded Disintegration at Hookend Recording Studios in Checkendon, Oxfordshire, with co-producer David M. Allen from late 1988 to early 1989. During production, founding member Lol Tolhurst was fired from the band.

Disintegration became the band's commercial peak, charting at number three in the United Kingdom and at number twelve in the United States, and producing several hit singles including "Lovesong", which peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100. It remains The Cure's highest selling record to date, with more than three million copies sold worldwide. It was greeted with a warm critical reception before later being acclaimed, eventually being placed at number 326 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic called it the "culmination of all the musical directions The Cure were pursuing over the course of the '80s".[5]

Background

The Cure's second album Seventeen Seconds (1980) established the group as a prominent gothic rock band characterised by what Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic described as "slow, gloomy dirges and Smith's ghoulish appearance". Three singles were released during 1982 and 1983 that were a significant divergence in style for The Cure; essentially, pop hits.[6] "The Love Cats" became The Cure's first single to infiltrate the top ten in the United Kingdom, peaking at number seven.[7] This shift is attributed to Smith's frustration over the band's labeling as a predictable gothic rock band: "My reaction to all those people ... was to make a demented and calculated song like 'Let's Go to Bed'."[8] Following the return of guitarist Porl Thompson and bassist Simon Gallup in 1984 and the addition of drummer Boris Williams in 1985, Smith and keyboardist Lol Tolhurst continued to integrate more pop-oriented themes with the release of the group's sixth studio album The Head on the Door (1985). With the singles "In-Between Days" and "Close to Me", The Cure became a viable commercial force in the United States for the first time.[9]

The band's 1987 double album Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me resulted in further commercial success, with a sold-out world tour booked in its wake. Despite the success, internal friction became prevalent. Tolhurst began to consume heavy amounts of alcohol, rendering him useless.[10] Roger O'Donnell was hired as a second keyboardist to pick up the slack. O'Donnell quickly realised that Tolhurst was essentially dead weight: "I couldn't see why [Tolhurst] was in the band. He could have afforded to hire a tutor and have daily lessons, but he wasn't interested in practicing. He just liked being in the group."[10] The rest of the band was equally unimpressed. As Tolhurst's alcohol consumption increased, Smith recalled that his behaviour was similar to that of "some kind of handicapped child being constantly poked with a stick".[10] At the end of the Kissing Tour in support of Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Smith became uncomfortable with the side effects of being a pop star and moved to Maida Vale (in West London) with fiancée Mary Poole. Regularly taking LSD to cope with his depression, Smith once again felt The Cure was being misunderstood and sought to return to the band's dark side with their next record.[11]

Recording and production

Robert Smith's depression prior to the recording of Disintegration gave way to the realisation on his twenty-ninth birthday that he would turn thirty in one year. This realisation was frightening to him, as he felt all the masterpieces in rock and roll had been completed well before the band members reached such an age. Smith consequently began to write music without the rest of the band. The material he had written instantly took a dismal, depressing form, which he credited to "the fact that I was gonna be thirty".[12] The Cure convened at Boris Williams' home in the summer of 1988 where Smith played his bandmates the demos he had recorded. If they had not liked the material, he was prepared to record them as a solo album: "I would have been quite happy to have made these songs on my own. If the group hadn't thought it was right, that would have been fine."[12] His bandmates liked the demos and began playing along. The group recorded thirty two songs at Williams' house with a 16-track recorder by the end of the summer.[12]

When the band entered Hook End Manor Studios in Oxfordshire, their attitude had turned sour towards Tolhurst's escalating alcohol abuse, although Smith insisted that his displeasure was caused by a meltdown in the face of recording The Cure's career-defining album and reaching thirty. Displeased with the swollen egos he believed his bandmates possessed, Smith entered what he considered to be "one of my non-talking modes" deciding "I would be monk-like and not talk to anyone. It was a bit pretentious really, looking back, but I actually wanted an environment that was slightly unpleasant". He sought to abandon the mood present on Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me and the pop singles they had released, and rather recreate the atmosphere of the band's fourth album Pornography (1982).

Tolhurst, meanwhile, was becoming a nuisance. The band found him impossible to work with, and he spent most of the recording process drunk and watching MTV. The members of the band, except for Smith, would taunt and physically abuse Tolhurst simply to get a reaction. Smith recalls that Tolhurst turned into someone he did not recognise: "I didn't know who he was any more and he didn't know who he was either. I used to despair and scream at the others because it was fucking insane the way we were treating him."[13] At that point, Smith was allowing Tolhurst to remain in The Cure simply because he felt an obligation as an old friend. The other band members, finally, threatened to quit if Tolhurst was not fired before the end of the recording session. When Tolhurst arrived to the mixing of the album excessively drunk, a shouting match ensued and he left the building furious; this effectively terminated his tenure with The Cure.[13] Smith and the rest of the group confirm he contributed nothing to the record.[14] Thereafter, O'Donnell became an integral member of The Cure, instead of simply a touring musician.[15] Despite Tolhurst's ejection from the group, Smith told NME in April 1989, "He'll probably be back by Christmas. He's getting married, maybe that's his comeback."[16] Tolhurst only returned briefly around 2011.

Music

Disintegration was Robert Smith's thematic return to a dark and gloomy aesthetic that The Cure had explored in the early 1980s. Smith deliberately sought to record an album that was depressing, as it was a reflection of the despondency he felt at the time.[17] The sound of the album was a shock to the band's American label Elektra Records; the label requested Smith shift the release date back several months. Smith recalled "they thought I was being 'wilfully obscure', which was an actual quote from the letter [Smith received from Elektra]. Ever since then I realised that record companies don't have a fucking clue what The Cure does and what The Cure means."[18] Despite rumours that Smith was one of the only contributors to the record, he confirmed that more than half of the dozen tracks on Disintegration had substantial musical input from the rest of the band.[18]

Disintegration is characterized by a significant usage of synthesizers and keyboards, slow, "droning" guitar progressions and Smith's introspective vocals. "Plainsong", the album's opener, "set the mood for Disintegration perfectly", according to journalist Jeff Apter, by "unravelling ever so slowly in a shower of synths and guitars, before Smith steps up to the mic, uttering snatches of lyrics ('I'm so cold') as if he were reading from something as sacred as the Dead Sea Scroll."[19] Smith felt the song was a perfect opener for the record, describing it as "very lush, very orchestral". The album's third track, "Closedown", contains layers of keyboard texture complemented with a slow, gloomy guitar line. The track was written by Smith as a means to list his physical and artistic shortcomings.[19] Despite the dark mood present throughout Disintegration, "Lovesong" was an upbeat track that became a hit in the United States. Ned Raggett of AllMusic noted the difference from other songs: "the Simon Gallup/Boris Williams rhythm section create a tight, serviceable dance groove, while Smith and Porl Thompson add further guitar fills and filigrees as well, adding just enough extra bite to the song. Smith himself delivers the lyric softly, with gentle passion."[20]

Much of the album made use of a considerable amount of guitar effects. "Prayers for Rain", a depressing track (Raggett noted: "the phrase 'savage torpor' probably couldn't better be applied anywhere else than to this song") sees Thompson and Smith "treating their work to heavy duty flanging, delay, backwards-run tapes and more to set the slow, moody crawl of the track."[21] Others, like the title track, are notable for "Smith's commanding lead guitar lines [that are] scaled to epic heights while at the same time buried in the mix, almost as if they're trying to burst from behind the upfront rhythm assault. Roger O'Donnell's keyboards add both extra shade and melody, while Smith's singing is intentionally delivered in a combination of cutting clarity and low resignation, at times further distorted with extra vocal treatments."[22]

While Disintegration mainly consists of sombre tracks, "Lovesong", "Pictures of You" and "Lullaby" were equally popular for their accessibility.[19] Smith wanted to create a balance on the album by including songs that would act as an equilibrium with those that were unpleasant. Smith wrote "Lovesong" as a wedding present for Mary Poole. The lyrics had a noticeably different mood than the rest of the record, but Smith felt it was an integral component of Disintegration: "It's an open show of emotion. It's not trying to be clever. It's taken me ten years to reach the point where I feel comfortable singing a very straightforward love song."[23] The lyrics were a notable shift in his ability to reveal affection. In the past, Smith felt it necessary to disguise or mask such a statement. He noted that without "Lovesong", Disintegration would have been radically different: "That one song, I think, makes many people think twice. If that song wasn't on the record, it would be very easy to dismiss the album as having a certain mood. But throwing that one in sort of upsets people a bit because they think, 'That doesn't fit'."[17] "Pictures of You", while upbeat, contained poignant lyrics ("Screamed at the make-believe/Screamed at the sky/You finally found all your courage to let it all go") with a "two-chord cascade of synthesizer slabs, interweaving guitar and bass lines, passionate singing and romantic lyrics."[19][24] "Lullaby" is composed of what Apter calls "sharp stabs" of rhythmic guitar chords with Smith whispering the words. The premise for the song came to Smith after remembering lullabies his father would sing him when he could not sleep: "[My father] would always make them up. There was always a horrible ending. They would be something like 'sleep now, pretty baby or you won't wake up at all.'"[19]

Release and reception

Disintegration was released in May 1989 and peaked at number three on the UK Albums Chart, the highest position the band had placed on the chart at that point.[25] In the UK, the lead single "Lullaby" became The Cure's highest charting hit in their home country when it reached number five.[25] In the US, due to its appearance in the film Lost Angels, the band's American label Elektra Records released "Fascination Street" as the first single.[26] The international follow-up single to "Lullaby", "Lovesong", became The Cure's highest charting hit in the United States, when it reached number two on the Billboard charts.[27] The success of Disintegration was such that the March 1990 final single "Pictures of You" reached number 24 on the British charts, despite the fact that the album had been released a year earlier.[28] Disintegration was certified silver (60,000 copies shipped) in the United Kingdom,[29] and by 1992 had sold more than three million copies worldwide.[30]

In a contemporary review for Rolling Stone, music critic Michael Azerrad gave the album three-and-a-half out of five stars and felt that, "while Disintegration doesn't break new ground for the band, it successfully refines what the Cure does best". He concluded, "Despite the title, Disintegration hangs together beautifully, creating and sustaining a mood of thoroughly self-absorbed gloom. If, as Smith has hinted, the Cure itself is about to disintegrate, this is a worthy summation."[31] Melody Maker reviewer Chris Roberts dismissed the claims that Disintegration was not a miserable record and, noting the tone of the album and its lack of melody ("You'll be lucky to find a tune on here. Or a gag"), he commented that "The Cure have almost invisibly stopped making pop records". Roberts summarised the album as "challenging and claustrophobic, often poignant, often tedious. It's nearly surprising."[32] NME praised Disintegration for its tunes, "from the first track 'Plainsong', a swaying, slow narrative, paralysing the listener with sex-poison, to Disintegration's last 'Untitled' Smith's lyrical agony of indecision is remorseless". Reviewer Barbara Ellen noted the large range of emotions in Smith's lyrics, "from deep, loving pink to an ugly, violent maroon and almost back again". Although she found the two extra-tracks superfluous, Ellen hailed Disintegration as "a mindblowing and stunningly complete album".[33] Q gave the album a three-star rating out of five, mainly comparing it to Joy Division's work. Writer Mat Snow observed: "The Cure have studied well the art of the tragic bass line, the hesitant and melancholy guitar lick, the funereal keyboard coloration". He concluded: "Disintegration is thus well-crafted [...], just don't tell me it's original".[34] Robert Christgau of The Village Voice gave the album a "C+" grade and felt that Smith attempts to appease a larger audience by broadening "gothic clichés" and "pumping his bad faith and bad relationship into depressing moderato play-loud keyb anthems far more tedious than his endless vamps".[35]

In a retrospective review for AllMusic, Stephen Thomas Erlewine gave Disintegration four-and-a-half out of five stars, and applauded the band by saying, "The Cure's gloomy soundscapes have rarely sounded so alluring [and] the songs – from the pulsating, ominous 'Fascination Street' to the eerie, string-laced 'Lullaby' – have rarely been so well-constructed and memorable."[5] Erlewine went on to praise Disintegration for being "darkly seductive", and "a hypnotic, mesmerizing record".[5] Pitchfork praised the record, admitting "Disintegration stands unquestionably as Robert Smith's magnum opus."[36] Writer Chris Ott noted that "scant few albums released in the 1980s can boast an opener as grand as 'Plainsong', the most breathtaking, shimmering anthem the band ever recorded."[36]

Disintegration has been included in numerous "Best Of" lists. Rolling Stone placed the record at number 326 on its 2003 compilation of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time".[37] The magazine's German counterpart placed Disintegration at number 184 on the same list.[38] The album was considered to be the best album of 1989 by Melody Maker,[39] 17th on Q magazine's "40 Best Albums of the 80s",[40] and 38th on Pitchfork's "Best Albums of the 80s".[36] The album placed at number 14 in Entertainment Weekly's "New Classics: The 100 Best Albums from 1983 to 2008."[41] In 2012, Slant Magazine listed the album at number 15 on its list of "Best Albums of the 1980s".[42] In a 2001 article in Rolling Stone, readers selected Disintegration as number 9 in of "the 10 Best Albums of the Eighties".[43] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[44]

The Prayer Tour and aftermath

Following completion of Disintegration, Smith noted that The Cure had "despite my best efforts, actually become everything that I didn't want us to become: a stadium rock band."[19] Furthermore, Smith claimed the album's title was the most appropriate one he could think of: "Most of the relationship with the band outside of the band fell apart. Calling it Disintegration was kind of tempting fate, and fate retaliated. The family idea of the group really fell apart too after Disintegration. It was the end of a golden period."[19]

The Prayer Tour began in Europe shortly after the release of the album. The band performed numerous high-profile concerts, including shows in front of more than 40,000 fans over two nights in Paris and their first performances in Eastern Europe. Following the European leg, the band elected to travel to North America for their upcoming US leg by boat, instead of plane. Smith and Gallup shared a fear of flight, and ultimately lamented the upcoming dates, wishing to reduce the number of concerts they booked. The record label and tour promoters strongly disagreed, and even proposed to add several new shows to the itinerary because of the success of Disintegration in the US. The first concert in the United States was at New Jersey's Giants Stadium, where 44,000 people attended; 30,000 tickets were purchased on the first day alone. The opening acts at Giant Stadium were: Pixies, Shelleyan Orphan and Love and Rockets along with a special appearance by The Bubblemen. The band were extremely displeased with the massive turnout; according to Roger O'Donnell: "We had been at sea for five days. The stadium was too big for us to take it all in. We've decided that we don't like playing stadiums that large." Smith recalls that "it was never our intention to become as big as this".[45]

The band's show at Dodger Stadium attracted roughly 50,000 attendees, grossing over US$1.5 million. The band's notably greater popularity in the United States—virtually every concert in the leg was sold out—caused Smith to break down, and threatened the band's future: "It's reached a stage where I personally can't cope with it," he said, "so I've decided this is the last time we're gonna tour."[45] Backstage, there were ongoing feuds between band members owing to the strife onset by Smith. He recalled that towards the end of the tour "I was tearing my hair out ... It was just a difficult tour."[45] Cocaine use was prevalent, and only ended up distancing Smith from his fellow band members.[45]

Upon returning to the United Kingdom in early October, Smith wanted nothing more to do with recording, promoting and touring for an album. In 1990 "Lullaby" won "Best Music Video of 1989" at the BRIT Awards. The Cure also released a live album titled Entreat (1991), which compiled songs entirely off Disintegration from their performance at Wembley Arena, and despite claims that The Cure would never tour again, Smith accepted an invitation to headline the Glastonbury Festival. O'Donnell, after two years with the group, left to pursue a solo career, and was replaced by the band's guitar technician Perry Bamonte. Smith, who was influenced by the acid house movement that had exploded in London that summer, released a predominantly electronic remix album, Mixed Up, in 1990.[45]

Track listing

All lyrics written by Robert Smith; all music composed by Smith, Simon Gallup, Roger O'Donnell, Porl Thompson, Boris Williams, and (officially, in credits) Lol Tolhurst.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Plainsong" | 5:12 |

| 2. | "Pictures of You" | 7:24 |

| 3. | "Closedown" | 4:16 |

| 4. | "Lovesong" | 3:29 |

| 5. | "Last Dance" | 4:42 |

| 6. | "Lullaby" | 4:08 |

| 7. | "Fascination Street" | 5:16 |

| 8. | "Prayers for Rain" | 6:05 |

| 9. | "The Same Deep Water as You" | 9:19 |

| 10. | "Disintegration" | 8:18 |

| 11. | "Homesick" | 7:06 |

| 12. | "Untitled" | 6:30 |

- Original CD and cassette copies of Disintegration listed "Last Dance" and "Homesick" as bonus tracks, as they were not included on the original vinyl issue of the album.

2010 deluxe edition disc two: Rarities 1988–1989

- "Prayers for Rain" – Robert Smith home demo (Instrumental) – 4/88

- "Pictures of You" – Robert Smith home demo (Instrumental) – 4/88

- "Fascination Street" – Robert Smith home demo (Instrumental) – 4/88

- "Homesick" – Band rehearsal (Instrumental) – 6/88

- "Fear of Ghosts" – Band rehearsal (Instrumental) – 6/88

- "Noheart" – Band rehearsal (Instrumental) – 6/88

- "Esten" – Band demo (Instrumental) – 9/88

- "Closedown" – Band demo (Instrumental) – 9/88

- "Lovesong" – Band demo (Instrumental) – 9/88

- "2Late" (alternate version) – Band demo (Instrumental) – 9/88

- "The Same Deep Water as You" – Band demo (Instrumental) – 9/88

- "Disintegration" – Band demo (Instrumental) – 9/88

- "Untitled" (alternate version) – Studio rough (Instrumental) – 11/88

- "Babble" (alternate version) – Studio rough (Instrumental) – 11/88

- "Plainsong" – Studio rough (Guide vocal) – 11/88

- "Last Dance" – Studio rough (Guide vocal) – 11/88

- "Lullaby" – Studio rough (Guide vocal) – 11/88

- "Out of Mind" – Studio rough (Guide vocal) – 11/88

- "Delirious Night" – Rough mix (vocal) – 12/88

- "Pirate Ships" (Robert Smith solo) – Rough mix (vocal) – 12/89

Disc three: Entreat Plus: Live at Wembley 1989

- "Plainsong"

- "Pictures of You"

- "Closedown"

- "Lovesong"

- "Last Dance"

- "Lullaby"

- "Fascination Street"

- "Prayers for Rain"

- "The Same Deep Water as You"

- "Disintegration"

- "Homesick"

- "Untitled"

Online only: Alternative Rarities: 1988–1989

- "Closedown" (RS Home Instrumental Demo 5/88) – 1:24

- "Last Dance" (RS Home Instrumental Demo 5/88) – 3:11

- "Lullaby" (RS Home Instrumental Demo 5/88) – 2:10

- "Tuned Out on RTV5" (Instrumental Rehearsal 6/88) – 2:20

- "Fuknnotfunk" (Instrumental Rehearsal 6/88) – 2:08

- "Babble" (Instrumental Rehearsal 6/88) – 2:08

- "Plainsong" (Instrumental Demo 9/88) – 2:24

- "Pictures of You" (Instrumental Demo 9/88) – 3:11

- "Fear of Ghosts" (Instrumental Demo 9/88) – 4:04

- "Fascination Street" (Instrumental Demo 9/88) – 3:45

- "Homesick" (Instrumental Demo 9/88) – 4:37

- "Delirious Night" (Instrumental Demo 9/88) – 3:26

- "Out of Mind" (Studio Instrumental Jam 10/88) – 2:40

- "2 Late" (Studio 'WIP' Mix 11/88) – 2:30

- "Lovesong" (Studio 'WIP' Mix 11/88) – 3:19

- "Prayers for Rain" (Studio 'WIP' Mix 11/88) –

- "The Same Deep Water as You" (Live Dallas Starplex 9/15/89) – 10:28

- "Disintegration" (Live Dallas Starplex 9/15/89) – 7:08

- "Untitled" (Live Dallas Starplex 9/15/89) – 7:07

- "Faith" (Live Rome Palaeur 6/4/89—Crowd Bootleg) – 14:06

These recordings were only found on www.thecuredisintegration.com, now closed.

Personnel

- Robert Smith – vocals, guitars, keyboards, 6-string bass, production, engineering

- Simon Gallup – bass guitar

- Porl Thompson – guitars

- Boris Williams – drums, percussion

- Roger O'Donnell – keyboards, piano

- Lol Tolhurst – credited with "other instrument"; basis for the song "Homesick"[46]

Production

- David M. Allen – production, engineering

- Richard Sullivan – engineering

- Roy Spong – engineering

Chart positions

Album

| Chart (1989) | Peak positions |

|---|---|

| UK Albums Chart[25] | 3 |

| US Billboard 200[47] | 12 |

| Australian ARIA Chart[48] | 9 |

| Austrian Albums Chart[49] | 5 |

| Canadian RPM Chart[50] | 22 |

| French Albums Chart[51] | 3 |

| Norwegian Albums Chart[52] | 7 |

| Swedish Albums Chart[53] | 10 |

| Swiss Albums Chart[54] | 4 |

Singles

| Year | Song | Peak positions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK [25] |

US Hot 100 [27] |

US Modern Rock [27] |

US Main Rock [27] |

US Dance Club [27] |

AUS [48] |

AUT [49] |

FRA [55] |

IRL [56] |

NOR [52] |

SWI [54] | ||

| 1989 | "Lullaby" | 5 | 74 | 23 | — | 31 | 5 | 28 | 22 | 3 | 5 | 14 |

| "Fascination Street" | — | 46 | 1 | 24 | 7 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| "Lovesong" | 18 | 2 | 2 | 27 | 8 | — | — | — | 13 | — | — | |

| 1990 | "Pictures of You" | 24 | 71 | 19 | — | 33 | — | — | — | 9 | — | — |

| "—" denotes releases that did not chart. | ||||||||||||

References

- Apter, Jeff (2005). Never Enough: The Story Of The Cure. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-8256-7340-5.

Notes

- ↑ Black, Johnny (26 April 1989). "Curious case of The Cure – Robert Smith". The Times. London.

- ↑ Sandall, Robert (30 April 1989). "How to gain the world and lose your soul – Record Choice". The Sunday Times. London.

- ↑ Staples, Derek (29 April 2010). "Check Out: Previously unreleased Cure demo". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "10 Essential Dream Pop Albums". Treble Media.

- 1 2 3 Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Disintegration – The Cure". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 June 2008.

- ↑ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Cure – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 June 2008.

- ↑ Apter 2005, p. 181.

- ↑ Apter 2005, p. 176.

- ↑ Apter 2005, p. 213–216.

- 1 2 3 Apter 2005, p. 227–229.

- ↑ Apter 2005, p. 230–231.

- 1 2 3 Apter 2005, p. 233.

- 1 2 Apter 2005, p. 236–238.

- ↑ Apter 2005, p. 230–240.

- ↑ Apter 2005, p. 241–244.

- ↑ Brown, James (8 April 1989). "Ten Years in Lipstick and Powder". NME.

- 1 2 Apter 2005, p. 234.

- 1 2 Apter 2005, p. 244.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Apter 2005, p. 242–243.

- ↑ Raggett, Ned. "Lovesong – The Cure". AllMusic. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ↑ Raggett, Ned. "Prayers for Rain – The Cure". AllMusic. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ↑ Raggett, Ned. "Disintegration – The Cure". AllMusic. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ↑ Apter 2005, p. 234–235.

- ↑ Raggett, Ned. "Pictures Of You – The Cure". AllMusic. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Roberts, David (ed.) (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). HIT Entertainment. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ↑ Apter 2005, p. 246.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Artist Chart History: Singles". Billboard. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ↑ Apter 2005, p. 249.

- ↑ "Certified Awards". BPI. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ Collins, Andrew (18 April 1992). "The Mansion Family". NME.

- ↑ Azerrad, Michael (13 July 1989). "Disintegration". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ↑ Roberts, Chris (6 May 1989). "Cracking Up [Disintegration album review]". Melody Maker.

- ↑ Ellen, Barbara (6 May 1989). "When Love Breaks Down [Disintegration album review]". NME.

- ↑ "Disintegration". Q. May 1989.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (28 November 1989). "Consumer Guide: Turkey Shoot". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 Ott, Chris (20 November 2002). "Staff Lists: Top 100 Albums of the 1980s". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time: The Cure, Disintegration". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone Germany. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ↑ "Best Albums of 1989". Melody Maker. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ↑ "The 40 Best Albums of the 80s". Q. August 2006.

- ↑ "New Classics: 100 Best Albums from 1983 to 2008". Entertainment Weekly. 20 June 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ "The 100 Best Albums of the 1980s". Slant Magazine. 5 March 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ "Rolling Stone Readers Pick the 10 Best Albums of the Eighties". Rolling Stone. 24 March 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (23 March 2010). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2074-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Apter 2005, p. 245–250.

- ↑ O'Donnell, Roger. "Disintegration Memories of Making the Album". Rogerodonnell.com. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ "Artist Chart History: Albums". Billboard.

- 1 2 "Discography The Cure". Australian-charts.com. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- 1 2 "Discographie The Cure" (in German). Austriancharts.at. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ↑ "RPM 100 Albums". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. 50 (7). 12 June 1989. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ↑ "Discography The Cure". lescharts.com. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- 1 2 "Discography The Cure". Norwegiancharts.com. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ↑ "Discography The Cure". Swedishcharts.com. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- 1 2 "Discography The Cure". Swisscharts.com. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ "Discographie The Cure" (in French). Lescharts.com. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ↑ "The Irish Charts – All there is to know". Irish Recorded Music Association. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

External links

- Disintegration (Adobe Flash) at Radio3Net (streamed copy where licensed)

- Disintegration (Deluxe Edition) (Adobe Flash) at Myspace (streamed copy where licensed)