Division of the Mongol Empire

Fragmentation of the Mongol Empire | |

| Date | 1259 - 1294 AD |

|---|---|

| Location | Mongol Empire |

| Participants | Ilkhanate, Yuan dynasty, Chagatai Khanate, Golden Horde |

| Outcome | The Mongol Empire fractured into four separate khanates |

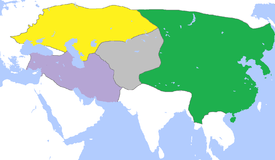

The division of the Mongol Empire began when Möngke Khan died in 1259 with no declared successor, precipitating infighting between members of the Tolui family line for the title of Great Khan that escalated to the Toluid Civil War. This civil war, along with the Berke–Hulagu war and the subsequent Kaidu–Kublai war greatly weakened the authority of the Great Khan over the entirety of the Mongol Empire and the empire fractured into autonomous khanates, including the Golden Horde in the northwest, the Chagatai Khanate in the middle, the Ilkhanate in the southwest, and the Yuan dynasty in the east based in modern-day Beijing, although the Yuan emperors held the nominal title of Khagan of the empire. The four khanates each pursued their own separate interests and objectives, and fell at different times.

Disunity

Dispute over succession

Möngke Khan's brother Hulagu Khan broke off his successful military advance into Syria, withdrawing the bulk of his forces to Mughan and leaving only a small contingent under his general Kitbuqa. The opposing forces in the region, the Christian Crusaders and Muslim Mamluks, both recognizing that the Mongols were the greater threat, took advantage of the weakened state of the Mongol army and engaged in an unusual passive truce with each other.[1]

In 1260, the Mamluks advanced from Egypt, being allowed to camp and resupply near the Christian stronghold of Acre, and engaged Kitbuqa's forces just north of Galilee, at the Battle of Ain Jalut. The Mongols were defeated, and Kitbuqa was executed. This pivotal battle marked the western limit for Mongol expansion, as the Mongols were never again able to make any serious military advances farther than Syria.[1]

In a separate part of the empire, another brother of Hulagu and Möngke, Kublai Khan, heard of the Great Khan's death at the Huai River in China. Rather than returning to the capital, he continued his advance into the Wuchang area of China, near the Yangtze River. Their younger brother Ariqboke took advantage of the absence of Hulagu and Kublai, and used his position at the capital to win the title of Great Khan for himself, with representatives of all the family branches proclaiming him as the leader at the kurultai in Karakorum. When Kublai learned of this, he summoned his own kurultai at Kaiping, where virtually all the senior princes and great noyans resident in North China and Manchuria supported his own candidacy over that of Ariqboke.

Civil war

Battles ensued between the armies of Kublai and those of his brother Ariqboke, which included forces still loyal to Möngke's previous administration. Kublai's army easily eliminated Ariqboke's supporters and seized control of the civil administration in southern Mongolia. Further challenges took place from their cousins, the Chagataids.[2][3][4] Kublai sent Abishka, a Chagataid prince loyal to him, to take charge of Chagatai's realm. But Ariqboke captured and then executed Abishka, having his own man Alghu crowned there instead. Kublai's new administration blockaded Ariqboke in Mongolia to cut off food supplies, causing a famine. Karakorum fell quickly to Kublai, but Ariqboke rallied and re-took the capital in 1261.[2][3][4]

In the southwestern Ilkhanate, Hulagu was loyal to his brother Kublai, but clashes with their cousin Berke, the ruler of the Golden Horde in the northwestern part of the empire, began in 1262. The suspicious deaths of Jochid princes in Hulagu's service, unequal distribution of war booty, and Hulagu's massacres of the Muslims increased the anger of Berke, who considered supporting a rebellion of the Georgian Kingdom against Hulagu's rule in 1259–1260.[5] Berke also forged an alliance with the Egyptian Mamluks against Hulagu and supported Kublai's rival claimant, Ariqboke.[6]

Hulagu died on February 8, 1264. Berke sought to take advantage and invade Hulagu's realm, but he died along the way, and a few months later Alghu Khan of the Chagatai Khanate died as well. Kublai named Hulagu's son Abaqa as a new Ilkhan, and Abaqa sought foreign alliances, such as attempting to form a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Europeans against the Egyptian Mamluks. Kublai nominated Batu's grandson Möngke Temür to lead the Golden Horde.[7] Ariqboqe surrendered to Kublai at Shangdu on August 21, 1264.[8]

Disintegration into four khanates

The establishment of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) by Kublai Khan accelerated the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire. The Mongol Empire fractured into four khanates including the Yuan dynasty, the Golden Horde, the Chagatai Khanate and the Ilkhanate. In 1304, a peace treaty among the khanates established the nominal supremacy of the Yuan dynasty over the western khanates. However, this supremacy was based on nothing like the same foundations as that of the earlier Khagans. Conflicts such as border clashes among them continued. An example would be the Esen Buqa–Ayurbarwada war occurred in the 1310s. Each of the four khanates continued to function as separate states and fell at different times.

Yuan dynasty

The transition of the capital of the Mongol Empire to Khanbaliq (Dadu, modern-day Beijing) by Kublai Khan in 1264 was opposed by many Mongols. Thus, Ariq Böke's struggle was for keeping the center of the Empire in Mongolia homeland. After Ariq Böke's death, the struggle was continued by Kaidu, a grandson of Ogedei Khan and lord Nayan.

By eliminating the Song dynasty, Kublai Khan completed the conquest of China. The fleets of the Yuan dynasty attempted to invade Japan in 1274 and 1281, but their ships were destroyed in sea storms named kamikazes (divine wind) on both occasions. The ordinary people experienced hardships during the Yuan dynasty. Hence, Mongol warriors rebelled against Kublai in 1289. Kublai Khan died in 1294 and was succeeded by Temür Khan, who continued the fight against Kaidu, which lasted until Kaidu's death in 1301. Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan came to power in 1312. The civil service examination system was instituted for the Yuan dynasty in 1313.[9]

A rebellion called the Red Turban Rebellion began in China in the 1350s[10] and the Yuan dynasty was overthrown by the Ming dynasty in 1368. The last Yuan emperor Toghon Temür fled north to Yingchang and died there in 1370. The Yuan remnants, which had retreated to Mongolia homeland, is known as the Northern Yuan dynasty and continued to resist the Ming China.

Golden Horde

The Golden Horde was founded by Batu, son of Jochi, in 1243. The Golden Horde included the Volga region, mountains of Ural, the steppes of the northern Black Sea, Fore-Caucasus, Western Siberia, Aral Sea and Irtysh bassin, and held principalities of Rus in tributary relations.

The capital was initially Sarai Batu and later Sarai Berke. This extensive empire weakened under rivalry of the descendants of Batu and split into Khanate of Kazan, Astrakhan Khanate, Crimean Khanate, Siberia Khanate, Great Horde, Nogai Horde and White Horde during the 15th century. A unified Rus conquered Khanate of Kazan in 1552, Astrakhan Khanate in 1556, Siberia Khanate in 1582, and the Russian Empire conquered Crimean Khanate in 1783.

Chagatai Khanate

The Chagatai Khanate separated in 1266 and covered Central Asia, Lake Balkhash, Kashgaria, Afghanistan and Zhetysu. It was split between settled Transoxania (Ma Wara'un-Nahr) in the west and nomadic Moghulistan in the east. It is claimed that parts of them still spoke Mongolian until the late 16th century.

Moghulistan gained strength during Timur (1395–1405), a warlord from Barlas clan. Timur defeated Tokhtamysh Khan of Golden Horde in 1395 and deprived him of Fore-Caucasus. He destroyed the army of the Turkish sultan near Angora, the event which delayed a Turkish conquest of the Byzantine Empire for half a century. The Timurid Empire fragmented shortly after he died.

Timur's grandson Ulugh Beg (1409–1449) ruled Transoxania and during his rule trade and economy of Transoxania achieved significant development. Ulugh Beg built an astronomical observatory near Samarkand in 1429 and wrote his work Zij-i-Sultani, which comprises the theories of astronomy and a catalogue of over 1000 stars with their precise positions on the celestial sphere.

A long rivalry of Moghulistan with the Oirats for trade routes ended with its defeat by the Oirats in 1530. Babur, a Timurid ruler of Kabul, conquered most of India in 1526 and founded the Mughal Empire. The Mughal Empire fractured into several lesser states in the 18th century and was conquered by the British Empire in 1858.

Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate, ruled by the House of Hulagu, formed in 1256 and comprised Iran, Iraq, Transcaucasus, eastern Asia Minor and Western Turkistan. While the early rulers of the khanate increasingly adopted Tibetan Buddhism, the Mongol rulers converted to Islam after the enthronement of Ilkhan Ghazan (1295–1304). In 1300, Rashid-al-Din Hamadani in cooperation with Mongol historians commenced writing Jami al-Tawarikh (Sudur un Chigulgan, Compendium of Chronicles) under Ghazan's order. The work was completed in 1311 during the reign of Ilkhan Öljeitü (1304–1316). Altan Debter written by a Mongol historian Bolad Chinsan served as a basis for writing Jami al-Tawarikh. After the death of Abu Sa'id (1316–1335) the Ilkhanate disintegrated rapidly into several states. The most prominent one was the Jalayrid dynasty, ruled by descendants of Mukhali of Jalair.

See also

- Mongol Empire

- Toluid Civil War

- Berke–Hulagu war

- Kaidu–Kublai war

- Esen Buqa–Ayurbarwada war

- Yuan dynasty in Inner Asia

- Turco-Mongols

- Turanism

- Tartary

- Inner Asia

References

- 1 2 Morgan. The Mongols. p. 138.

- 1 2 Wassaf. p. 12.

- 1 2 Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 109.

- 1 2 Barthold. Turkestan. p. 488.

- ↑ L. N.Gumilev, A. Kruchki. Black legend

- ↑ Barthold. Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion. p. 446.

- ↑ Prawdin. Mongol Empire and Its Legacy. p. 302.

- ↑ Weatherford. p. 120.

- ↑ The Mongol Empire and Its Legacy, by Reuven Amitai, David Orrin Morgan, p267

- ↑ The Cambridge history of China, Volume 7, pg 42