Drosophila

| Drosophila | |

|---|---|

| |

| Drosophila pseudoobscura | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Family: | Drosophilidae |

| Subfamily: | Drosophilinae |

| Genus: | Drosophila Fallén, 1823 |

| Type species | |

| Musca funebris Fabricius, 1787 | |

| Subgenera | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Oinopota Kirby & Spence, 1815 | |

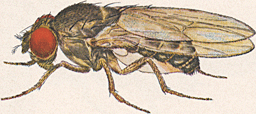

Drosophila (/drəˈsɒfᵻlə, drɒ-, droʊ-/[1][2]) is a genus of small flies, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "fruit flies" or (less frequently) pomace flies, vinegar flies, or wine flies, a reference to the characteristic of many species to linger around overripe or rotting fruit. They should not be confused with the Tephritidae, a related family, which are also called fruit flies (sometimes referred to as "true fruit flies"); tephritids feed primarily on unripe or ripe fruit, with many species being regarded as destructive agricultural pests, especially the Mediterranean fruit fly. One species of Drosophila in particular, D. melanogaster, has been heavily used in research in genetics and is a common model organism in developmental biology. The terms "fruit fly" and "Drosophila" are often used synonymously with D. melanogaster in modern biological literature. The entire genus, however, contains more than 1,500 species[3] and is very diverse in appearance, behavior, and breeding habitat.

Etymology

The term "Drosophila", meaning "dew-loving", is a modern scientific Latin adaptation from Greek words δρόσος, drósos, "dew", and φίλος, phílos, "loving" with the Latin feminine suffix -a.

Morphology

Drosophila species are small flies, typically pale yellow to reddish brown to black, with red eyes. Many species, including the noted Hawaiian picture-wings, have distinct black patterns on the wings. The plumose (feathery) arista, bristling of the head and thorax, and wing venation are characters used to diagnose the family. Most are small, about 2–4 mm long, but some, especially many of the Hawaiian species, are larger than a house fly.

Lifecycle and ecology

Habitat

Drosophila species are found all around the world, with more species in the tropical regions. They can be found in deserts, tropical rainforest, cities, swamps, and alpine zones. Some northern species hibernate. Most species breed in various kinds of decaying plant and fungal material, including fruit, bark, slime fluxes, flowers, and mushrooms. The larvae of at least one species, D. suzukii, can also feed in fresh fruit and can sometimes be a pest.[4] A few species have switched to being parasites or predators. Many species can be attracted to baits of fermented bananas or mushrooms, but others are not attracted to any kind of baits. Males may congregate at patches of suitable breeding substrate to compete for the females, or form leks, conducting courtship in an area separate from breeding sites.

Several Drosophila species, including D. melanogaster, D. immigrans, and D. simulans, are closely associated with humans, and are often referred to as domestic species. These and other species (D. subobscura, Zaprionus indianus[5][6][7]) have been accidentally introduced around the world by human activities such as fruit transports.

Reproduction

Males of this genus are known to have the longest sperm cells of any studied organism on Earth, including one species, Drosophila bifurca, that has a sperm 58 mm (2.3 in) long.[8] The cells are mostly tail, and are delivered to the females in tangled coils. The other members of the genus Drosophila also make relatively few giant sperm cells, with that of D. bifurca being the longest.[9] D. melanogaster sperm cells are a more modest 1.8 mm long, although this is still about 35 times longer than a human sperm. Several species in the D. melanogaster species group are known to mate by traumatic insemination.[10]

Drosophila species vary widely in their reproductive capacity. Those such as D. melanogaster that breed in large, relatively rare resources have ovaries that mature 10–20 eggs at a time, so that they can be laid together on one site. Others that breed in more-abundant but less nutritious substrates, such as leaves, may only lay one egg per day. The eggs have one or more respiratory filaments near the anterior end; the tips of these extend above the surface and allow oxygen to reach the embryo. Larvae feed not on the vegetable matter itself, but on the yeasts and microorganisms present on the decaying breeding substrate. Development time varies widely between species (between 7 and more than 60 days) and depends on the environmental factors such as temperature, breeding substrate, and crowding. Numerous studies have shown that fruit flies lay eggs using an environmental circle. If fruit flies laid eggs at nighttime during which the environmental conditions were advantageous, the eggs could not be susceptible to desiccation from parasites. As a result, the offspring reproduced from these eggs would have greater fitness compared to offspring that were reproduced from eggs laid during the day. Since eggs are laid with a biological clock, D. melanogaster became adaptive to their environmental cycles, which showed a major advantage.[11]

Their median lifespan is 35–45 days.[12]

Laboratory-cultured animals

D. melanogaster is a popular experimental animal because it is easily cultured en masse out of the wild, has a short generation time, and mutant animals are readily obtainable. In 1906, Thomas Hunt Morgan began his work on D. melanogaster and reported his first finding of a 'white' (eyed) mutant in 1910 to the academic community. He was in search of a model organism to study genetic heredity and required a species that could randomly acquire genetic mutation that would visibly manifest as morphological changes in the adult animal. His work on Drosophila earned him the 1933 Nobel Prize in Medicine for identifying chromosomes as the vector of inheritance for genes. This and other Drosophila species are widely used in studies of genetics, embryogenesis, and other areas.

However, some species of Drosophila are difficult to culture in the laboratory, often because they breed on a single specific host in the wild. For some, it can be done with particular recipes for rearing media, or by introducing chemicals such as sterols that are found in the natural host; for others, it is (so far) impossible. In some cases, the larvae can develop on normal Drosophila lab medium, but the female will not lay eggs; for these it is often simply a matter of putting in a small piece of the natural host to receive the eggs. The Drosophila Species Stock Center in San Diego maintains cultures of hundreds of species for researchers.

Microbiome

Like other metazoans, Drosophila is associated with various bacteria in its gut. The fly gut microbiota or microbiome seems to have a central influence on Drosophila fitness and life history characteristics. The microbiota in the gut of Drosophila represents an active current research field.

Predators

Drosophila species are prey for many generalist predators such as robber flies. In Hawaii, the introduction of yellowjackets from the mainland United States has led to the decline of many of the large species. The larvae are preyed on by other fly larvae, staphylinid beetles, and ants.

Systematics

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The genus Drosophila as currently defined is paraphyletic (see below) and contains 1,450 described species,[3][13] while the total number of species is estimated at thousands.[14] The majority of the species are members of two subgenera: Drosophila (about 1,100 species) and Sophophora (including D. (S.) melanogaster; around 330 species). The Hawaiian species of Drosophila (estimated to be more than 500, with roughly 380 species described) are sometimes recognized as a separate genus or subgenus, Idiomyia,[3][15] but this is not widely accepted. About 250 species are part of the genus Scaptomyza, which arose from the Hawaiian Drosophila and later recolonized continental areas.

Evidence from phylogenetic studies suggests these genera arose from within the genus Drosophila:[16][17]

- Liodrosophila Duda, 1922

- Mycodrosophila Oldenburg, 1914

- Samoaia Malloch, 1934

- Scaptomyza Hardy, 1849

- Zaprionus Coquillett, 1901

- Zygothrica Wiedemann, 1830

- Hirtodrosophila Duda, 1923 (position uncertain)

Several of the subgeneric and generic names are based on anagrams of Drosophila, including Dorsilopha, Lordiphosa, Siphlodora, Phloridosa, and Psilodorha.

- Further information: List of Drosophila species

Drosophila species genome project

Drosophila species are extensively used as model organisms in genetics (including population genetics), cell biology, biochemistry, and especially developmental biology. Therefore, extensive efforts are made to sequence drosphilid genomes. The genomes of these species have been fully sequenced:[18]

- Drosophila (Sophophora) melanogaster

- Drosophila (Sophophora) simulans

- Drosophila (Sophophora) sechellia

- Drosophila (Sophophora) yakuba

- Drosophila (Sophophora) erecta

- Drosophila (Sophophora) ananassae

- Drosophila (Sophophora) pseudoobscura

- Drosophila (Sophophora) persimilis

- Drosophila (Sophophora) willistoni

- Drosophila (Drosophila) mojavensis

- Drosophila (Drosophila) virilis

- Drosophila (Drosophila) grimshawi

The data have been used for many purposes, including evolutionary genome comparisons. D. simulans and D. sechellia are sister species, and provide viable offspring when crossed, while D. melanogaster and D. simulans produce infertile hybrid offspring. The Drosophila genome is often compared with the genomes of more distantly related species such as the honeybee Apis mellifera or the mosquito Anopheles gambiae.

The modEncode consortium is currently sequencing eight more Drosophila genomes,[19] and even more genomes are being sequenced by the i5K consortium.[20]

Curated data are available at FlyBase.

References

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach, James Hartmann and Jane Setter, eds., English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ↑ "Drosophila". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- 1 2 3 Gerhard Bächli (1999–2006). "TaxoDros: the database on taxonomy of Drosophilidae".

- ↑ Mark Hoddle. "Spotted Wing Drosophila (Cherry Vinegar Fly) Drosophila suzukii". Center for Invasive Species Research. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ↑ C. R. Vilela (1999). "Is Zaprionus indianus Gupta, 1970 (Diptera, Drosophilidae) currently colonizing the Neotropical region?". Drosophila Information Service. 82: 37–39.

- ↑ Kim van der Linde; Gary J. Steck; Ken Hibbard; Jeffrey S. Birdsley; Linette M. Alonso; David Houle (2006). "First records of Zaprionus indianus (Diptera, Drosophilidae), a pest species on commercial fruits, from Panama and the United States of America". Florida Entomologist. 89 (3): 402–404. doi:10.1653/0015-4040(2006)89[402:FROZID]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ S. Castrezana (2007). "New records of Zaprionus indianus Gupta, 1970 (Diptera, Drosophilidae) in North America and a key to identify some Zaprionus species deposited in the Drosophila Tucson Stock Center". Drosophila Information Service. 90: 34–36.

- ↑ Scott Pitnick; Greg S. Spicer; Therese A. Markow (1995). "How long is a giant sperm?". Nature. 375 (6527): 109. doi:10.1038/375109a0. PMID 7753164.

- ↑ Dominique Joly; Nathalie Luck; Béatrice Dejonghe (2007). "Adaptation to long sperm in Drosophila: correlated development of the sperm roller and sperm packaging". Journal of Experimental Zoology B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 310B (2): 167–178. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21167. PMID 17377954.

- ↑ Kamimura, Yoshitaka (2007-08-22). "Twin intromittent organs of Drosophila for traumatic insemination". Biol Lett. The Royal Society. 3 (4): 401–404. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0192. PMC 2391172

. PMID 17519186.

. PMID 17519186. - ↑ Howlader, G., Sharma, K. V (2006). Circadian regulation of egg-laying behavior in fruit flies Drosophila melanogaster. The Journal of Insect Physiology, 52, 779-785

- ↑ Broughton SJ, Piper MD, Ikeya T, Bass TM, Jacobson J, Driege Y, Martinez P, Hafen E, Withers DJ, Leevers SJ, Partridge L (2005). "Longer lifespan, altered metabolism, and stress resistance in Drosophila from ablation of cells making insulin-like ligands". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (8): 3105–10. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405775102. PMC 549445

. PMID 15708981.

. PMID 15708981. - ↑ Therese A. Markow; Patrick M. O'Grady (2005). Drosophila: A guide to species identification and use. London: Elsevier. ISBN 0-12-473052-3.

- ↑ Colin Patterson (1999). Evolution. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8594-0.

- ↑ Irina Brake; Gerhard Bächli (2008). Drosophilidae (Diptera). World Catalogue of Insects. pp. 1–412. ISBN 978-87-88757-88-0.

- ↑ Patrick O'Grady; Rob DeSalle (2008). "Out of Hawaii: the origin and biogeography of the genus Scaptomyza (Diptera: Drosophilidae)". Biology Letters. 4 (2): 195–199. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0575. PMC 2429922

. PMID 18296276.

. PMID 18296276. - ↑ James Remsen; Patrick O'Grady (2002). "Phylogeny of Drosophilinae (Diptera: Drosophilidae), with comments on combined analysis and character support". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 24 (2): 249–264. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00226-9. PMID 12144760.

- ↑ "12 Drosophila Genomes Project". Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ↑ "modEncode Comparative Genomics white paper" (PDF). ENCODE. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ↑ "i5k species nomination summary". Retrieved December 13, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Drosophila. |

- Fly Base FlyBase is a comprehensive database for information on the genetics and molecular biology of Drosophila. It includes data from the Drosophila Genome Projects and data curated from the literature.

- Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project

- Annual Drosophila Research Conference

- AAA: Assembly, Alignment and Annotation of 12 Drosophila species

- UCSC Genome browser

- TaxoDros: The database on Taxonomy of Drosophilidae

- UC San Diego Drosophila Stock Center breeds hundreds of species and supplies them to researchers

- FlyMine is an integrated database of genomic, expression and protein data for Drosophila

- The Drosophila Virtual library is library of Drosophila on web

- Drosophila Melanogaster contains further information.

- C-CAMP Fly facility - In India microinjection service for the generation of transgenic lines, Screening Platforms, Drosophila strain development

.jpg)