Duchy of Aquitaine

| Duchy of Aquitaine | ||||||||||

| Duché d'Aquitaine | ||||||||||

| Fief of Francia (602 – late 7th century), independent duchy (intermittently late 7th century – 769) | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

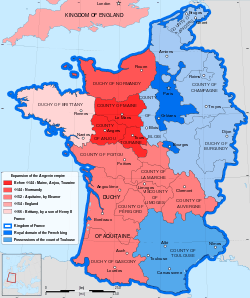

Map of France in 1154 | ||||||||||

| Capital | Not specified | |||||||||

| Languages | Medieval Latin Old Occitan | |||||||||

| Religion | Christianity | |||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | |||||||||

| Duke of Aquitaine | ||||||||||

| • | 860–866 | Ranulf I of Aquitaine | ||||||||

| • | 1058–1086 | William VIII of Aquitaine | ||||||||

| • | 1126–1137 | William X | ||||||||

| • | 1137–1204 | Eleanor of Aquitaine | ||||||||

| • | 1422–1453 | Henry IV of Aquitaine | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | |||||||||

| • | Duke appointed by The Carolingian kings | 602 | ||||||||

| • | Annexed by Kingdom of France | 1453 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

The Duchy of Aquitaine (Occitan: Ducat d'Aquitània, French: Duché d'Aquitaine, IPA: [dy.ʃe da.ki.tɛn]) was a historical fiefdom in western, central and southern areas of present-day France to the south of the Loire River, although its extent, as well as its name, fluctuated greatly over the centuries, at times comprising much of what is now southwestern France (Gascony) and central France.

It originated in the 7th century as a duchy under Frankish suzerainty, ultimately a recreation of the Roman provinces of Aquitania Prima and Secunda. As a duchy, it broke up after the conquest of the independent Aquitanian duchy of Waifer, going on to become a sub-kingdom within the Carolingian Empire, eventually subsumed in West Francia after the 843 partition of Verdun. It reappeared as a duchy, and in the High Middle Ages, an enlarged Aquitaine pledged loyalty to the Angevin dynasty, who also happened to reign in England. Their claims in France triggered the Hundred Years' War, in which the kingdom of France emerged victorious in the 1450s, with many incorporated areas coming to be ruled directly by the French kings.

History

Early history

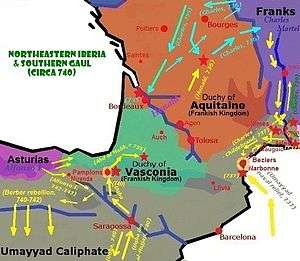

Gallia Aquitania fell under Visigothic rule in the 5th century. It was conquered by the Franks under Clovis I in 507, as a result of the Battle of Vouillé. During the 6th and early 7th century, it was under direct rule of Frankish kings, divided between the realms of Childebert II and Guntram in the Treaty of Andelot of 587. Under Chlothar II, Aquitaine was again integral part of Francia, but after Chlothar's death in 628, his heir Dagobert I granted a subkingdom in southern Aquitaine to his younger brother Charibert II. This subkingdom, consisting of Gascony and the southern fringe of Aquitaine proper, is conventionally known as "Aquitaine" and forms the historical basis for the later duchy. Charibert campaigned successfully against the Basques, but after his death in 632, they revolted again, in 635 subdued by an army sent by Dagobert (who was at the same time forced to deal with a rebellion in Brittany).

The duchy of Aquitaine as a quasi-independent realm within the Frankish empire established itself during the second half of the 7th century, certainly by 700 under Odo the Great. The first duke is on record under the name of Felix, and as having ruled from about 660. As his successor Lupus, he probably owed allegiance to the Frankish kings.[1] Odo succeeded Lupus in 700 and signed a peace treaty with Charles Martel. He inflicted on the Moors a crushing defeat at the Battle of Toulouse in 721. However, Charles Martel coveted the southern realm, crossed the Loire in 731 and looted much of Aquitaine. Odo engaged the Franks in battle, but lost and came out weakened. Soon after this battle, in 732, the Moors raided Vasconia and Aquitaine as far north as Poitiers and defeated Odo twice near Bordeaux. Odo saw no option but to invoke the aid of Charles Martel and pledge allegiance to the Frankish prince.

Odo was succeeded by his son Hunald, who reverted to former independence, so defying the Frankish Mayor of the Palace Charles Martel's authority. The Carolingian leader attacked Hunald twice in 735 and 736, but was unable to totally subdue the duke and an army put together by counts of key Aquitanian towns, e.g. Bourges, Limoges, etc. Eventually, Hunald retired to a monastery, leaving both the kingdom and the continuing conflict to Waifer, or Guaifer. For some years Waifer strenuously carried on an unequal struggle with the Franks, but his assassination in 768 marked the demise of Aquitaine's relative independence.

As a successor state to the Roman province of Gallia Aquitania and the Visigothic Kingdom (418–721), Aquitania (Aquitaine) and Languedoc (Toulouse) inherited the Visigothic Law and Roman Law which had combined to allow women more rights than their contemporaries in other parts of Europe. Particularly with the Liber Judiciorum, which was codified in 642 and 643 and expanded in the Code of Recceswinth in 653, women could inherit land and title and manage it independently from their husbands or male relations, dispose of their property in legal wills if they had no heirs, and women could represent themselves and bear witness in court by age 14 and arrange for their own marriages by age 20.[2] As a consequence, male-preference primogeniture was the practiced succession law for the nobility.

Carolingian kingdom of Aquitaine

The autonomous and troublesome duchy of Aquitaine was conquered by the Franks in 769, after a series of revolts against their suzerainty. In order to avoid a new demonstration of Aquitain particularism, Charlemagne decided to organize the land within his kingdom.

After the Carolingian conquest, the duchy ceased to exist as such, whose powers were taken over by the counts (dukes) of Toulouse, main seat of the Carolingian government in the Midi, represented by Chorso and, after being deposed, by Charlemagne's trustee William (of Gellone), a close relative of his. In 781, he made his third son, Louis then 3 years of age, king of Aquitaine. The Carolingian Kingdom of Aquitaine subordinated to the Carolingian king or (later) emperor based in Francia (Austrasia, Neustria). It included not only Aquitaine proper, but also Gothia, Vasconia (Gascony) and the Carolingian possessions in Spain as well. In 806, Charlemagne planned to divide his empire between his sons. Louis received Provence and Burgundy as additions to his kingdom.

When Louis succeeded Charlemagne as emperor in 814, he granted Aquitaine to his son Pepin I, after whose death in 838 the nobility of Aquitaine chose his son Pepin II of Aquitaine (d. 865) as their king. The emperor Louis I, however, opposed this arrangement and gave the kingdom to his youngest son Charles, afterwards the emperor Charles the Bald. Confusion and conflict resulted, eventually falling in favor of Charles; although from 845 to 852 Pepin II was in possession of the kingdom, at Eastertide 848 in Limoges, the magnates and prelates of Aquitaine formally elected Charles as their king Later, at Orléans, he was anointed and crowned by Wenilo, archbishop of Sens.[3] In 852, Pepin II was imprisoned by Charles the Bald, who soon afterwards pronounced his own son Charles as the ruler of Aquitaine. On the death of the younger Charles in 866, his brother Louis the Stammerer succeeded to the kingdom, and when, in 877, Louis became king of the Franks, Aquitaine was fully absorbed into the Frankish crown.

By a treaty made in 845 between Charles the Bald and Pepin II, the kingdom had been diminished by the loss of Poitou, Saintonge and Angoumois in the northwest of the region, which had been given to Rainulf I, count of Poitiers. The title of Duke of Aquitaine, already revived, was now borne by Rainulf, although it was also claimed by the counts of Toulouse. The new duchy of Aquitaine, including the three districts already mentioned, remained in the hands of Ramulf's successors, despite disagreement with their Frankish overlords, until 893 when Count Rainulf II was poisoned by order of King Charles III, or Charles the Simple. Charles then bestowed the duchy upon William the Pious, count of Auvergne, the founder of the abbey of Cluny, who was succeeded in 918 by his nephew, Count William II, who died in 926.

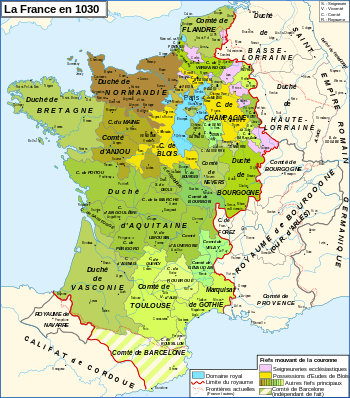

A succession of dukes followed, one of whom, William IV, fought against Hugh Capet, king of France, and another of whom, William V, called the Great, was able to strengthen and extend his authority considerably, although he yielded the proffered Lombard crown rather than fight Conrad II for it. William's duchy almost reached the limits of the old Roman Gallia Aquitania but did not stretch south of the Garonne, a district which was in the possession of the Gascons. William died in 1030. Odo or Eudes (d. 1039) joined Gascony to Aquitaine.

Angevin Empire

The Ramnulfids had become the dominant power in southwestern France by the end of the 11th century. By marriage rather than conquest, their possessions passed into the "Angevin Empire" under the English crown by 1135.

William IX, Duke of Aquitaine (d. 1127) who succeeded to the dukedom in 1087, gained fame as a crusader and a troubadour. His son William X (d. 1137) married his daughter Eleanor to Louis VII of France, and Aquitaine went as her dowry. But when Eleanor was divorced from Louis and married Henry II of England in 1152, the duchy passed to the English Crown. Having suppressed a revolt in his new possession, Henry gave it to his son Richard. When Richard died in 1199, it reverted to Eleanor, and on her death five years later, it was absorbed into the English crown and henceforward followed the fortunes of the other English possessions in France, such as Normandy and Anjou, ultimately leading to the Hundred Years' War between the French and English crowns.

Aquitaine as it came to the English kings stretched from the Loire to the Pyrenees, but its range was limited to the southeast by the extensive lands of the counts of Toulouse. The name Guienne, a corruption of Aquitaine, seems to have come into use about the 10th century, and the subsequent history of Aquitaine is merged in that of Gascony and Guienne.

Hundred Years' War

In 1337, King Philip VI of France reclaimed the fief of Aquitaine (essentially corresponding to Gascony) from Edward III of England. Edward in turn claimed the title of King of France, by right of his descent from his maternal grandfather King Philip. This triggered the Hundred Years' War, in which both the Plantagenets and the House of Valois claimed the supremacy over Aquitaine. In 1360, both sides signed the Treaty of Bretigny, in which Edward renounced the French crown but remained sovereign Lord of Aquitaine (rather than merely duke). However, when the treaty was broken in 1369, both these English claims and the war resumed. In 1362, King Edward III, as Lord of Aquitaine, made his eldest son Edward, Prince of Wales, Prince of Aquitaine. In 1390, King Richard II, son of Edward the Black Prince appointed his uncle John of Gaunt Duke of Aquitaine. That title passed on to John's descendants although they belonged to the crown because John of Gaunt's son, Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Hereford, managed to successfully usurp the crown from Richard II, therefore 'inheriting' the title Lord of Aquitaine from his father, which was passed down to his descendants as they became Kings. His son, Henry V of England, ruled over Aquitaine as King of England and Lord of Aquitaine from 1400 to 1422. He invaded France and emerged victorious at the siege of Harfleur and the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. He succeeded in obtaining the French crown for his family by the Treaty of Troyes in 1420. Henry V died in 1422, when his son Henry VI inherited the French throne at the age of less than a year; his reign saw the gradual loss of English control of France.

The Valois kings of France, claiming supremacy over Aquitaine, granted the title of duke to their heirs, the Dauphins, during 1345 and 1415: John II (1345–50), Charles VII (1392?–1401), and Louis (1401–15). French victory was complete with the Battle of Castillon of 1453. England and France nominally remained at war for another 20 years, but England was in no position to continue its campaign, due to its escalating internal conflicts. The Hundred Years' War was formally concluded with the Treaty of Picquigny of 1475. With the end of the Hundred Years' War, Aquitaine returned under direct rule of the king of France and remained in the possession of the king. Only occasionally was the title of "duke of Aquitaine" granted to another member of the dynasty, and then as a purely nominal distinction.

Geography and subdivisions

The historical duchy of Aquitaine does not correspond to the French region now known as Aquitaine; it was further north, including parts of what are now the regions of Pays de la Loire, Centre, Limousin, Poitou-Charentes and Auvergne. Over the duration of its existence, the duchy of Aquitaine came to incorporate the duchy of Vasconia and the county of Toulouse (comprising parts of what are now the regions of Midi-Pyrénées and Languedoc-Roussillon). Toulouse again became detached and passed to the kingdom of France by 1271. Vasconia (Gascogne) on the other hand remained an integral part of the duchy of Aquitaine and represents the bulk of the region now known as Aquitaine.

The county of Aquitaine as it stood in the High Middle Ages, then, was bordering the Pyrenees to the south (Navarre, Aragon and Barcelona, formerly the Marcha Hispanica) and the county of Toulouse and the kingdom of Burgundy (Arelat to the east. To the north, it bordered on Bretagne, Anjou, Blois and Bourbonnais, all of which had passed to the kingdom of France by the 13th century.

- Aquitania proper

- County of Poitou

- County of La Marche

- County of Angoulême

- County of Périgord

- County of Auvergne (passed to the royal domain in 1271)

- County of Velay

- County of Saintonge

- Lordship of Déols

- Lordship of Issoudun

- Viscounty of Limousin

- Duchy of Gascogne (Gascony), personal union with Aquitaine since the 7th century (Felix of Aquitaine), quasi-independent during the 9th and 10th centuries, re-conquered into Angevine Aquitaine in 1053.

- County of Agenais

- County of Toulouse (quasi-independent from 778, reverted to the royal domain in 1271)

- County of Quercy

- County of Rouergue

- County of Gevaudan

- Viscounty of Albi

- Marquisat of Gothia

See also

References

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, p. 252.

- ↑ Wemple, Suzanne Fonay; Women in the Fifth to the Tenth Century. In: Klapisch-Zuber, Christine; A History of Women: Book II. Silences of the Middle Ages, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England. 1992, 2000 (5th printing). Chapter 6, p 74.

- ↑ Against this background of conflicted loyalties must be seen the career of Wenilo.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aquitaine". Encyclopædia Britannica. 02 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 252–53.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aquitaine". Encyclopædia Britannica. 02 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 252–53.

- Emile Mabille, (1870) Le Royaume D'Aquitaine Et Ses Marches Sous Les Carlovingiens

- Jean Penant, (2009) Occitanie, l'épopée des origines