Kingdom of Navarre

| Kingdom of Navarre | ||||||||||||

| Nafarroako Erresuma (Basque) Reino de Navarra (Spanish) Royaume de Navarre (French) Regnum Navarrae (Latin) | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

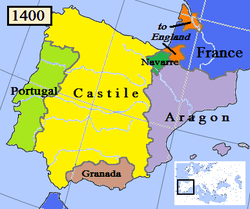

Kingdom of Navarre in 1400 (dark green). | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Pamplona (Iruñea) | |||||||||||

| Languages | Basque (spoken)[1] Latin (written)[1] Navarro-Aragonese (administrative; spoken)[2][3] Occitan[1] Hebrew (written in Aljama)[4] Arabic (written or formal)[5][6] | |||||||||||

| Religion | Majority religion: Roman Catholic Minority religions: Sephardic Judaism (until 1515) Sunni Islam (until 1515) Reformed (1560-1594) | |||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | |||||||||||

| Monarch | ||||||||||||

| • | 824–852 | Íñigo Arista (first) | ||||||||||

| • | 1610–1620 | Louis II (last. French kingdom) | ||||||||||

| • | 1830–1841 | Isabel II of Spain (last. Spanish kingdom) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | |||||||||||

| • | Rebelled against the Frankish Empire | 824 | ||||||||||

| • | Name changes from Pamplona to Navarre | 1004 | ||||||||||

| • | Annexed to Castile | 1512 | ||||||||||

| • | Charles I of Spain abandons the northern part | 1528 | ||||||||||

| • | Personal union with France under Henry III/IV | 1589 | ||||||||||

| • | Northern part merged into the Kingdom of France | 1620 | ||||||||||

| • | Spanish Kingdom of Navarra is abolished. Navarra becomes a province of Spain after the Ley Paccionada of Navarra | 1841 | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||

The Kingdom of Navarre (/nəˈvɑːr/; Basque: Nafarroako Erresuma, Spanish: Reino de Navarra, French: Royaume de Navarre, Latin: Regnum Navarrae), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona, was a Basque-based kingdom[7] that occupied lands on either side of the western Pyrenees, alongside the Atlantic Ocean between present-day Spain and France.

The primeval Kingdom of Pamplona was formed when the native chieftain Íñigo Arista was elected or declared King in Pamplona (traditionally in 824),[8] and led a revolt against the regional Frankish authority.

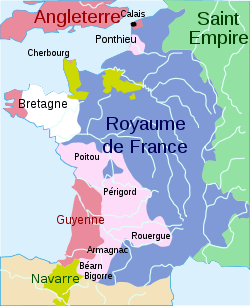

The southern part of the kingdom was conquered by the Crown of Castile in 1512 (permanently in 1524), becoming part of the unified Kingdom of Spain. The northern part of the kingdom remained independent, but it joined with France by personal union in 1589 when King Henry III of Navarre inherited the French throne as Henry IV of France, and in 1620 it was merged into the Kingdom of France. The monarchs of this unified state took the title "King of France and Navarre" until its fall in 1792, and again during the Bourbon Restoration from 1814 until 1830 (with a short break in 1815).

Etymology

There are similar earlier toponyms but the first documentation[9] of Latin navarros appears in Eginhard's chronicle of the feats of Charles the Great. Other Royal Frankish Annals give nabarros. There are two proposed etymologies[9] for the name of Navarra/Nafarroa/Naparroa:

- Basque nabar (declined absolute singular nabarra): "brownish", "multicolor", which would be a contrast with the green mountain lands north of the original County of Navarre.

- Basque naba/Castilian nava ("valley", "plain", present across Spain) + Basque herri ("people", "land").

The linguist Joan Coromines consider naba as not clearly Basque in origin but as part of a wider pre-Roman substrate.

Early historic background

The kingdom of Pamplona and then Navarre formed part of the traditional territory of the Vascones, a pre-Roman tribe who occupied the southern slope of the western Pyrenees and part of the shore of the Bay of Biscay. The area was completely conquered by the Romans by 74 BC. It was first part of the Roman province of Citerior, then of the Tarraconensis province. After that it was part of the conventus Caesaraugustanus. The Roman empire influenced the area in urbanization, language, infrastructure, commerce, and industry.

After the decline of the Western Roman Empire, neither the Visigoths nor the Arabs succeeded in permanently occupying the western Pyrenees. The western Pyrenees passages were the only ones allowing good transit through the mountains, other than those through the southern Pyrenees. That made the region strategically important from early in its history.

The Franks under Charlemagne extended their influence and control towards the south, occupying several regions of the north and east of the Iberian Peninsula. It is not clear how solid the Frankish control over Pamplona was. On August 15, 778, after the retreating Charlemagne had demolished the walls of Pamplona, the Basque tribes annihilated his rearguard, led by Roland, in a confrontation at a mountain passage known to history as the Battle of Roncevaux Pass.

In response, the Cordoban Emirate launched a campaign to place the region under their firm control, and in 781 defeated a local leader called Ibn Balask ("son of Velasco"). It placed a muwallad governor, Mutarrif ibn Musa, in Pamplona. The same year the Basque leader, Jimeno 'the Strong,' submitted to the Emir.

In 799, Mutarrif ibn Musa was killed by a pro-Frankish faction whose leader Velasco gained control of the region. In 806 and 812 Pamplona fell into the Franks' hands. Due to difficulties at home, the Frankish rulers could not give full attention to the outlying borderlands, and the country gradually withdrew entirely from their allegiance. The Emirate also attempted to reestablish its control in the region, and in 816 fought a battle against the "enemy of Allah", Balask al-Yalaski (Velasco the Gascon), who was killed along with Garcia Loup, kinsman of Alfonso II of Asturias, Sancho, premier knight in Pamplona, and Saltan, premier knight of the Mayus (pagans).

History of the kingdom

Establishment by Iñigo Arista

In 816, Louis the Pious removed Seguin as Duke of Vasconia, which initiated a rebellion.[10] The rebel Garcia Jiménez arose in his place, and was killed in turn in 818. Louis' son Pepin, then King of Aquitaine, stamped out the Vasconic revolt in Gascony. He next hunted the chieftains who had taken refuge in southern Vasconia, i.e. Pamplona and Navarre, no longer controlled by the Franks. He sent an army led by the counts Aeblus and Aznar-Sanchez (the latter being appointed lord, but not duke, of Vasconia by Pepin after suppressing the uprising in the Duchy of Vasconia), accomplishing their goals with no resistance in Pamplona (still lacking walls after the 778 destruction). On the way back, however, they were ambushed and defeated in Roncesvaux by a probable joint Vasconic-Banu Qasi force. Out of this pattern of resistance against both Frankish and Cordoban interests, the Basque chieftain Íñigo Arista took power.[11] Tradition tells he was elected as king of Pamplona in 824, giving rise to a dynasty of kings in Pamplona that would last for eighty years.

Pamplona and Navarre are cited as separate entities in a Frankish Carolingian chronicle. Pamplona is cited in 778 by another Frankish account as a Navarrese stronghold, while this may be put down to their vague knowledge of the Basque territory. They distinguished Navarre and its main town in 806 though ("In Hispania, vero Navarrensis et Pampelonensis"), while the Chronicle of Fontenelle quotes "Induonis et Mitionis, ducum Navarrorum". However, Arab chroniclers make no such distinctions, and just talk of the Baskunisi, a transliteration of Vascones,[12] since a big majority of the population was Basque.[13][14] The primitive Navarre may have comprised the valleys of Goñi, Gesalaz, Lana, Allin, Deierri, Berrueza and Mañeru, which later formed the merindad of Estella.

Earliest historic period

In 905, the dynasty founded by Íñigo Arista was overthrown through the machinations of neighboring princes,[15] and Sancho I Garcés (905–25),[15] nephew of the Count of Ribagorza, was placed in the throne. He fought against the Moors with repeated success and joined Ultra-Puertos, or Basse-Navarre, to his own dominions, also extending its territory as far as Nájera. As a thanksgiving for his victories, he founded in 924 the convent of Albelda. Before his death, he had driven all Moors from the country. His son and eventual successor, Garcia Sanchez I (931–70), who had the support of his energetic and diplomatic mother Toda (Teuda) Aznárez of the line of Arista, likewise engaged in a number of conflicts with the Moors. At this time, the county of Aragon, previously only nominally a vassal state, came under the direct control of the kings of Pamplona.

The Chronicle of Albelda (last update in 976) outlines the extension in 905 of the Kingdom of Pamplona for the first time. It extended to Nájera and Arba (arguably Araba). Some historians believe that this suggests that it included the Western Basque Country as well:

.gif)

In era DCCCCXLIIII surrexit in Panpilona rex nomine Sancio Garseanis. Fidei Xpi inseparabiliterque uenerantissimus fuit, pius in omnibus fidefibus misericorsque oppressis catholicis. Quid multa? In omnibus operibus obtimus perstitit. Belligerator aduersus gentes Ysmaelitarum multipficiter strages gessit super Sarrazenos. Idem cepit per Cantabriam a Nagerense urbe usque ad Tutelam omnia castra. Terram quidem Degensem cum opidis cunctam possideuit. Arbam namque Panpilonensem suo iuri subdidit, necnon cum castris omne territorium Aragonense capit. Dehinc expulsis omnibus biotenatis XX' regni sue anno migrauit a seculo. Sepultus sancti Stefani portico regnat cum Xpo in polo (Obiit Sancio Garseanis era DCCCCLXIIII (A marg.)).[16]

In the Era 944 [AD 905] arose in Pamplona a king named Sancio Garseanis. He was a man of unbreakable devotion to the faith of Christ, pious with all the faithful and merciful with oppressed Catholics. What more? In all his actions he performed as a great warrior against the people of the Ismailites; he inflicted multiple disasters on the Saracens. This same captured all the fortified places in the Cantabria, from the city of Nájera to Tudela. Indeed he possessed all the land of Degium [Monjardín, near Lizarra] with its towns. The "Arba" of Pamplona he submitted to his law, and conquered as well all the country of Aragon [then Jaca and nearby lands] with its fortresses. Later, after suppressing all infidels, the twentieth year of his reign he left this world. Buried in the portal of Saint Stephen [Monjardín], he reigns with Christ in Heaven (King Sancho Garcés died in the era 964 [925] (marginal note)).

.gif)

In 934, Abd-ar-Rahman III intervened in the kingdom, beginning a period of frequent punitive campaigns from Córdoba and submission to tributary status by Pamplona. Garcia Sanchez's son, Sancho II Garces, nicknamed Abarca, ruled as king of Pamplona from 970 to 994. Around 985 Sancho II Garces crossed the Pyrenees to Gascony, which was being raided by the Normans, probably in rescue of his brother-in-law William Sánchez, but had to make his way back on the news of a Muslim attack against Pamplona. The passes were, however, covered in snow, but the expeditionary force contrived some proper shoes ("Abarca" in Basque) to make it through the mountains, which allowed them to catch the besieging Muslim assailants by surprise and overcome them, hence the nickname.

The Historia General de Navarra by Jaime del Burgo says that on the occasion of the donation of the villa of Alastue by the king of Pamplona to the monastery of San Juan de la Peña in 987, he styled himself "King of Navarre", the first time that title had been used. In many places he appears as the first King of Navarre and in others the third; however, he was at least the seventh king of Pamplona.

Under Sancho III the Great (reigned 1000/4–1035) and his immediate successors, Pamplona reached the height of its power and extent. Navarre had joined in the Christian coalition that defeated and killed Al-Mansur Ibn Abi Aamir in 1002, leading to civil war that eventually resulted in the dissolution of the Córdoba Caliphate, replacing the dominant power on the peninsula with a collection of ineffectual Taifa states and freeing Navarre from the continual campaigns and tribute. Inheriting Pamplona, including Aragon, Sancho III conquered Ribagorza and Sobrarbe, which had been depopulated since the collapse of Moorish control. The minority of García Sánchez of Castile forced the County of Castile to submit to vassalage under Sancho, the count's brother-in-law, and García's 1028 assassination allowed Sancho to appoint his younger son Ferdinand as count. He also exerted a protectorate over Gascony. He seized the country of the Pisuerga and the Cea, which belonged to the Kingdom of León, and marched armies to the heart of that kingdom forcing king Bermudo III of León to flee to a Galician refuge. Sancho thereby effectively ruled the north of Iberia from the boundaries of Galicia to those of the count of Barcelona.

Division of Sancho's domains

At its greatest extent the Kingdom of Navarre included all the modern Spanish province; the northern slope of the western Pyrenees called by the Spaniards the ultra puertos ("country beyond the mountain passes") or French Navarre; the Basque provinces of Spain and France; the Bureba, the valley between the Basque mountains and the Montes de Oca to the north of Burgos; the Rioja and Tarazona in the upper valley of the Ebro. On his death, Sancho divided his possessions among his four sons. Sancho the Great's realm was never again united (until Ferdinand the Catholic): Castile was permanently joined to Leon, whereas Aragon enlarged its territory, joining Catalonia through a marriage.

Of Sancho's sons, Garcia of Najera inherited the Kingdom of Pamplona and merged into it the eastern part of the County of Castile (from the proximity of Burgos and Santander); the rest of Castile and the lands between the Pisuerga and the Cea went to the eldest son, Fernando; to Gonzalo were given Sobrarbe and Ribagorza; lands in Aragon were allotted to the bastard son Ramiro. The realm was divided thus once more into Navarre, Aragón, and Castile.

Younger son Ferdinand I inherited a diminished County of Castile, but after acquiring the Kingdom of León, he used the title of King of Castile as well, and he enlarged his realm by various means (see Kingdom of Castile).

The bastard son of Sancho III, Ramiro de Aragon, founded the Navarrese dynasty of Aragon.

García, the eldest legitimate son, was to be feudal overlord of his brothers, but he was soon challenged by his brothers, leading to the first partition of the kingdom after his death in the Battle of Atapuerca, in 1054.

Ecclesiastical affairs

In this period of independence, the ecclesiastical affairs of the country reached a high state of development. Sancho the Great was brought up at Leyra, which was also for a short time the capital of the Diocese of Pamplona. Beside this see, there existed the Bishopric of Oca, which was united in 1079 to the Diocese of Burgos. In 1035 Sancho the Great re-established the See of Palencia, which had been laid waste at the time of the Moorish invasion. When, in 1045, the city of Calahorra was wrested from the Moors, under whose dominion it had been for more than three hundred years, a see was also founded here, which in the same year absorbed the Diocese of Najera and, in 1088, the Diocese of Alava, the jurisdiction of which covered about the same ground as that of the present Diocese of Vitoria. To Sancho the Great, also, the See of Pamplona owed its re-establishment, the king having, for this purpose, convoked a synod at Leyra in 1022 and one at Pamplona in 1023. These synods likewise instituted a reform of ecclesiastical life with the above-named convent, as a centre.

Navarre's dismemberment

First partition

García Sánchez III (1035–54) soon found himself struggling against his brothers, especially the ambitious Ferdinand of Castile. He died fighting against him in Atapuerca, near Burgos, then the border of Pamplona.

He was succeeded by Sancho IV (1054–76) of Peñalén, who was murdered by his brothers. This crime caused a dynastic crisis that the Castilian and Aragonese monarchs used to their benefit.

The royal title was transferred to the Aragonese line but Castile swiftly annexed two thirds of the realm from the historical border of the Atapuerca–Santander line to a vague partition-line at the Ega valley, near Estella.

It is in this period of Aragonese domination that the name of Navarre first appears historically, referring initially to a county that comprised only the central part of modern Navarre.

The three Aragonese rulers, Sancho Ramirez (1076–94) and his son Pedro Sanchez (1094–1104) conquered Huesca; Alfonso "the Fighter", 1104–34, brother of Pedro Sanchez, secured for the country its greatest territorial expansion. He wrested Tudela from the Moors (1114), re-conquered the entire country of Bureba, which Navarre had lost in 1042, and advanced into the current Province of Burgos; in addition, Roja, Najera, Logroño, Calahorra, and Alfaro were subject to him. He also annexed Labourd, with its strategic port of Bayonne, but lost its coastal half to the English soon after. The remainder has been part of Navarre since then and eventually came to be known as Lower Navarre.

Restoration

This status quo stood for two decades until Alfonso the Battler, dying without heirs, decided to give his realm away to the military orders, particularly the Templars. This decision was rejected by the courts (parliaments) of both Aragon and Navarre, which then chose separate kings.

García Ramírez, known as the Restorer, is the first King of Navarre to use such a title. He was Lord of Monzón, a grandson of Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, El Cid, and a descendant by illegitimate line of king García Sánchez III. Sancho Garcia, known as Sancho VI "the Wise" (1150–94), a patron of learning, as well as an accomplished statesman, fortified Navarre within and without, granted charters (fueros) to a number of towns, and was never defeated in battle. He was the first king to issue royal documents entitling him rex Navarrae or rex Navarrorum, appealing to a wider power base, defined as politico-juridical by Urzainqui (a "populus"), beyond Pamplona and the customary rex Pampilonensium.[17] As attested in the charters of San Sebastián and Vitoria-Gasteiz (1181), the natives are called Navarri, as well as in another contemporary document at least, where those living to the north of Peralta are defined as Navarrese.[18]

The Restorer and Sancho the Wise were faced with an ever increased intervention of Castile in Navarre. In 1170, Alfonso VIII of Castile and Eleanor, daughter of Henry II Plantagenet, married, with the Castilian king claiming Gascony as part of the dowry. It turned out a much needed pretext for the invasion of Navarre during the following years (1173-1176), with a special focus on Navarre's coastal districts, coveted by Castile in order to become a maritime power.[19] In 1177, the dispute was submitted to arbitration by Henry II of England. The Navarrese made their point on a number of claims, namely "the proven will of the locals" (fide naturalium hominum suorum exhibita), the assassination of the King Sancho Garces IV of Navarre by the Castilians (per violentiam fuit expulsus, 1076), law and custom, while the Castilians made their case by citing the Castilian takeover following the death of Sancho Garces IV, the dynastic links of Alfonso with Navarre, and the conquest of Toledo.[20] The king Henry II did not dare issue a verdict utterly based on legal grounds as presented by both sides, instead deciding to refer them back to the boundaries held by both kingdoms at the start of their reigns in 1158, besides agreeing to a truce of seven years. It thus confirmed the permanent loss of the Bureba and Rioja areas for the Navarrese.[21] However, soon on, Castile breached the compromise, starting a renewed effort to harass Navarre both in the diplomatic and military arena.[22]

The rich dowry of Berengaria, the daughter of Sancho VI the Wise and Blanche of Castile, made her a desirable catch for Richard I of England. His aged mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, crossed the Pyrenean passes to escort Berengaria to Sicily, eventually to wed Richard in Cyprus, 12 May 1191. She is the only Queen of England who never set foot in England during her reign. The reign of Sancho the Wise's successor, the last king of the male line of Sancho the Great and of kings of Pamplona, king Sancho VII the Strong (Sancho el Fuerte) (1194–1234), was more troubled. He appropriated the revenues of churches and convents, granting them instead important privileges; in 1198 he presented to the See of Pamplona his palaces and possessions in that city, this gift being confirmed by Pope Innocent III on 29 January 1199.

Second partition

However, in 1199 Alfonso VIII of Castile, son of Sancho III of Castile and Blanche of Navarre, determined to own coastal Navarre, a strategic region that would allow Castile much easier access to European wool markets and would isolate Navarre as well, launched a massive expedition, while Sancho the Strong was on an international diplomatic voyage to Tlemcen (modern Algeria).

The cities of Vitoria and Treviño resisted the Castilian assault but the Bishop of Pamplona was sent to inform them that no reinforcements would arrive. Vitoria then surrendered but Treviño did not, having to be conquered by force of arms.

By 1200 the conquest of Western Navarre was complete. Castile granted to the fragments of this territory (exceptions: Treviño, Oñati, directly ruled from Castile) the right of self-rule, based on their traditional customs (Navarrese right), that came to be known as fueros. Alava was made a county, Biscay a lordship and Guipuscoa just a province.

The late reign of Sancho the Strong

_with_the_Royal_Crest.svg.png)

The greatest glory of Sancho el Fuerte was the part he took in the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212), where, through his valour, the victory of the allied Christians over the Caliph En-Nasir was made decisive. He retired and died in el Encerrado. His elder sister Berengaria, Queen of England, had died childless some years earlier. His deceased younger sister Blanca, countess of Champagne, had left a son, Theobald IV of Champagne.

Thus the Kingdom of Navarre, though the crown was still claimed by the kings of Aragon, passed by marriage to the House of Champagne, firstly to the heirs of Blanca, who were simultaneously counts of Champagne and Brie, with the support of the Navarrese Parliament (Cortes).

Navarre in the High Middle Ages

Theobald I made of his court a centre where the poetry of the troubadours that had developed at the court of the counts of Champagne was welcomed and fostered; his reign was peaceful. His son, King Theobald II (1253–70), married King Louis IX of France's daughter Isabella and accompanied his saintly father-in-law upon his crusade to Tunis. On the homeward journey, he died at Trapani in Sicily, and was succeeded by his brother, King Henry I, who had already assumed the reins of government during his absence, but reigned only three years (1271–74). His daughter, Queen Joan I, ascended as minor and the country was once again invaded from all sides. The queen and her mother, Blanche of Artois, sought refuge at the court of King Philip III of France. His son, the future King Philip IV of France, had become engaged to the young sovereign and married her in 1284. In 1276, at the time of the negotiations for this marriage, Navarre effectively passed into French control.

The Kingdom of Navarre remained in personal union with the Kingdom of France until the death of King Charles I (Charles IV of France) in 1328. He was succeeded by his niece, Queen Joanna II, daughter of King Louis I (Louis X of France), and nephew-in-law, King Philip III. Joanna waived all claim to the throne of France and accepted as compensation for the counties of Champagne and Brie those of Angoulême, Longueville, and Mortain.

King Philip III devoted himself to the improvement of the laws of the country, and joined King Alfonso XI of Castile in battle against the Moors of 1343. After the death of his mother (1349), King Charles II assumed the reins of government (1349–87). He played an important part in the Hundred Years' War and in the French civil unrest of the time, and on account of his deceit and cruelty he received the ephithet of the Bad. He gained and lost possessions in Normandy and, later in his reign, the Navarrese Company acquired island possessions in Greece.

His eldest son, on the other hand, King Charles III, surnamed the Noble, gave the land once more a peaceful and happy government (1387–1425), exerted his strength to the utmost to lift the country from its degenerate condition, reformed the government, built canals, and made navigable the tributaries of the Ebro flowing through Navarre. As he outlived his legitimate sons, he was succeeded by his daughter, Queen Blanche I (1425–42), and son-in-law, King John II (1397–1479).

Navarre under the Foix-Albret and the Spanish conquest

Foix and Albret dynasties

After Queen Blanche I of Navarre's death in 1441, Navarre was mired in continued disputes over royal succession. King John II was ruling in Aragon in the name of his brother, Alfonso V of Aragon. He left his son, the King Charles, Prince of Viana, only with the rank of governor, whereas Queen Blanche I had designed that he should succeed her, as it was the custom. In 1450, John II himself came back to Navarre, and urged on by his ambitious second wife Juana Enriquez endeavoured to obtain the succession for their son Ferdinand.

Mirroring inter-clan disputes during the bloody War of the Bands in the rest of Basque territories, in 1451 Navarre split in two confederacies over royal succession with ramifications both within and out of Navarre: the Agramonts and the Beaumonts. In the violent civil war that broke out, the Agramonts sided with John II, and the Beaumonts—named after their leader, the chancellor, John of Beaumont—espoused the cause of Charles, Prince of Viana.[23]:15 The fights involved the big aristocracy and their junior branches, who carried on the feuds of their senior lines and thrived on weak royal authority, or one that was often absent from Navarre.[24]:252

The unhappy prince Charles was defeated by his father at Aibar in 1451, and held a prisoner for two years, during which he wrote his famous Chronicle of Navarre, a major source of present knowledge about the period. After his release, the above Charles sought in vain the assistance of King Charles VII of France and his uncle Alfonso V (who resided in Naples). In 1460 he was again imprisoned at the instigation of his stepmother, but the Catalonians rose in revolt at this injustice, and he was again liberated and named governor of Catalonia. He died in 1461, poisoned by his stepmother, King Ferdinand II of Aragon's mother Juana Enríquez, without being able to retake the reigns of the kingdom of Navarre. He named as his heir his next sister, Queen Blanche II, but was immediately imprisoned by John II, and died in 1464. While this episode of the civil war came to an end, it inaugurated a period of instability including on-off periods of struggle and uprisings all the way to the Spanish conquest (1512).

On Charles' demise in 1461, Eleanor of Navarre, Countess of Foix and Béarn, was proclaimed Princess of Viana, but the instability took a toll—the south-western tip of Navarre was occupied by Henry IV of Castile, i.e. the Sonsierra (Oyon, Laguardia, in present-day Álava), and Los Arcos. All of them were permanently lost for Navarre, and annexed to Castile (1463), a territorial loss upheld by the French king Louis XI in Bayonne on 23 April 1463.[23]:15

John II continued to rule as king up to 1479, when Queen Eleanor succeeded him for only 15 days and died, leaving the crown to her grandson, Francis Phoebus, but Eleanor's death (1479) inaugurated another period of instability. Eleanor's 13-year-old granddaughter Catherine I of Navarre succeeded her brother Francis Phoebus, in accordance to his will (1483). As a minor she remained under the guardianship of her mother, Magdalena of Valois, and was sought by Ferdinand the Catholic as a bride. However, another claimant to the throne was stubbornly trying to stop her, John of Foix, Viscount of Narbonne, brother-in-law of future king of Louis XII of France. John of Foix even entitled himself king of Navarre and sent diplomats to Ferdinand II of Aragon in that capacity, invoking the French Salic Law, but Navarre was not France.

Pressure built up on Catherine's regent Magdalena of Valois during the former's age minority. She eventually decided to marry her to the 7-year-old John of Albret, despite the Parliament of Navarre's preference for John of Aragon, son of Ferdinand and Isabella. Magdalena was intent on saving their French possessions when she made the decision.[23]:17 However, many in Navarre stirred and the Beaumont party rose up, while the Agramonts split over the marriage. Ferdinand II of Aragon in turn reconsidered his diplomatic policy on Navarre. The crown of Navarre resorted to diplomacy, as it was its default international policy. They signed the Treaty of Valencia on 21 March 1488, whereby trade flowed again between Navarre and the Aragon-Castile tandem. Still Ferdinand did not recognize Catherine, imposed the presence of Castilian troops in Navarre and a ban to allow French troops in both the kingdom and the principality of Béarn.[23]:17

| "Before the sacrament of the holy unction is completed, this blessed coronation of yours, it is necessary for Your Royal Majesties to swear an oath to the people, as the monarchs of Navarre preceding you did formerly, so that the people can also swear an oath to you as set by custom [...] we swear [...] to the prelates, nobles [...] and men of the cities and good towns and all the people of Navarre [...] from all across the Kingdom of Navarre [...] all the fueros, as well as the mores, and customs, tax exemptions, liberties, privileges held by each of you—either here or absent." |

| Instructions to the monarchs Catherine and John III on the mandatory oath owed to the Kingdom of Navarre, and the oath itself, ahead of their coronation (1494). |

The Navarrese loathed the Inquisition, a coercive cross-border tribunal fostered by Ferdinand II, but the doors of Navarre (Tudela) finally opened to the Church institution between 1486 and 1488 pushed by the Aragonese monarch's threats—still in 1510 the authorities of Tudela decreed the expulsion of the monk "calling himself inquisitor." Not that Catherine and John III benefited from French royal support, just the opposite both Charles VIII of France and Louis XII of France, the latter proclaimed king in 1498, pushed hard to have John of Foix declared king.

Finally, following a short period of peace with Ferdinand II after a treaty was signed, in January 1494 the coronation of the royal family took place in Pamplona. The monarchs Catherine I and John III swore an oath to respect the liberties of Navarre, and the proclamation was celebrated with a week-long festival, while the ceremony was not attended by the Aragonese bishops with jurisdiction in Navarre. During this period, the realm of Navarre-Beárn was defined by Emperor Maximilian I's diplomat Müntzer as a nation like Switzerland.[25]:16

In the above treaty reached with the Navarrese rulers, King Ferdinand II renounced to wage or allow war on Navarre or Béarn from Castile, but the attempt to restore royal authority and patrimony met with the resistance of the defiant count of Lerin Louis of Beaumont, whose estates where confiscated.

Catherine and John III's guardian Magdalena of Valois died in 1495 and John's father Alain I of Albret signed another treaty with Ferdinand, whereby the count of Lerín should abandon Navarre, receiving in compensation real estate and various enclaves in the recently conquered Granada. However, in exchange for that, Alain made an array of painful concessions: Ferdinand received the count of Lerín's patrimony, and he got control of important fortresses across Navarre, including keeping a garrison in Olite at the heart of the kingdom. Not only that, Queen Catherine's 1-year-old daughter Magdalena should be sent and raised in Castile with a plan on a future marriage, and so was done—she died young in Castile (1504).[23]:18–19 However, following developments in France, the whole treaty was reverted in 1500, and another compromise was reached with Ferdinand of Aragon, so ensuring peace for another 4 years.

Spanish conquest

Nevertheless, Ferdinand the Catholic did not relinquish his long-cherished designs on Navarre. In 1506, the 53-year-old married secondly Germaine of Foix (aged 16), the daughter of Catherine's uncle who had attempted to claim Navarre over his deceased elder brother's under-age children. However, their infant son died shortly after birth, ending hopes of potentially inheriting Navarre. He kept intervening directly or indirectly in the internal affairs of Navarre by means of the Beaumont party. In 1508, the Navarrese royal troops finally suppressed a rebellion of the count of Lerin after a long standoff. On a letter to the rebellious count of Lerín, the king of Aragon insisted that while he may take over one stronghold or another, he should use "theft, deceit and bargain" instead of violence (23 July 1509).

When Navarre refused to join one of many Holy Leagues against France and declared itself neutral, Ferdinand asked the Pope to excommunicate Albret, which would have legitimised his attack. The Pope was reluctant to label the Crown of Navarre as schismatic explicitly in a first bull against the French and the Navarrese (21 July 1512), but Ferdinand's pressure bore fruit when a (second) bull named Catherine and John III "heretic" (18 February 1513). On 18 July 1512, Don Fadrique de Toledo was sent to invade Navarre in 1512 in the context of the second phase of the War of the League of Cambrai.

Unable to face the powerful Castilian-Aragonese army, Jean d'Albret fled to Béarn (Orthez, Pau, Tarbes). Pamplona, Estella, Olite, Sanguesa, and Tudela were captured up to September. The Agramont party sided with Queen Catherine while most of the Beaumont party lords (but not all) supported the occupiers. In October 1512, the legitimate King John III returned with an army recruited north of the Pyrenees and attacked Pamplona without success. By the end of December, the Castilians were back in St-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

After this failure, the Navarrese Cortes (Parliament) had no option but pledge loyalty to King Ferdinand of Aragon. In 1513, the first Castilian viceroy took a formal oath to respect Navarrese institutions and law (fueros). However, the Spanish Inquisition was extended into Navarre, the Jews had already been forced into conversion or exile by the Alhambra Decree in Castile and Aragon, and now the Jewish community of Navarre and the Muslims of Tudela suffered its persecution.

There were two more attempts at liberation in 1516 and 1521, both supported by popular rebellion, especially the second one. It was in 1521 that the Navarrese came closest to regaining their independence. As the liberation army commanded by General Asparros approached Pamplona, the citizens revolted and besieged the military governor, Iñigo de Loyola, in his newly built castle. Tudela and other cities also declared their loyalty to the House of Albret. The Navarrese-Béarnese army did manage to liberate all the Kingdom, and Castile was at first distracted due to only recently overcoming the Revolt of the Comuneros. But the Revolt was defeated at almost the same time as the reconquest, and Asparros faced a huge and united Castilian army at the Battle of Noáin on 30 June 1521. Asparros was captured, and the army completely defeated.

Independent Navarre north of the Pyrenees

A small portion of Navarre north of the Pyrenees, Lower Navarre, along with the neighbouring Principality of Béarn survived as an independent kingdom which passed by inheritance. Navarre received from King Henry II, the son of Queen Catherine and King John III, a representative assembly, the clergy being represented by the bishops of Bayonne and Dax, their vicars-general, the parish priest of St-Jean-Pied-de-Port, and the priors of Saint-Palais, Utziat and Harambels (Haranbeltz).

Queen Joan III converted to Calvinism in 1560 and, thereupon, promoted a translation of the Bible into Basque; it is one of the first books published in this language. She and her son, Henry III, led the Huguenot party in the French Wars of Religion. In 1589, Henry became the sole rightful claimant to the crown of France, though he was not recognized as such by many of his subjects until his conversion to Catholicism four years later.

When Labourd and Upper Navarre were shaken by the Basque witch trials in 1609 and 1610, many sought refuge in Lower Navarre. The last independent king of Navarre, Henry III (reigned 1572–1610), succeeded to the throne of France as Henry IV in 1589, founding the Bourbon dynasty. Between 1620 and 1624, Lower Navarre and Béarn were incorporated into France proper by Henry's son, Louis XIII of France (Louis II of Navarre). The Parliament of Navarre with a seat in Pau was also created by merging the Royal Council of Navarre and the sovereign Council of Béarn.

The 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees put an end to the litigation over the definite French-Spanish borders and to any possibility of a French-Navarrese dynastic claim over the Spanish Navarre. The title of King of Navarre continued to be used by the Kings of France until the French Revolution in 1792, and was revived again during the Restoration, 1814–30. Since the rest of Navarre was in Spanish hands, the kings of Spain also carried the title of king of Navarre, which they do today.

The crown and the kingdom: A constitutional foundation

_-_Navarre.svg.png)

As the Kingdom of Navarre was originally organized, it was divided into merindades, districts governed by a merino ("mayorino", a sheriff), the representative of the king. They were the "Ultrapuertos" (French Navarre), Pamplona, Estella, Tudela and Sangüesa. In 1407 the merindad of Olite was added. The Cortes of Navarre began as the king's council of churchmen and nobles, but in the course of the 14th century the burgesses were added. Their presence was due to the fact that the king had need of their co-operation to raise money by grants and aids, a development that was being paralleled in England.

The Cortes henceforth consisted of the churchmen, the nobles and the representatives of twenty-seven (later thirty-eight) "good towns"—towns which were free of a feudal lord, and, therefore, held directly of the king. The independence of the burgesses was better secured in Navarre than in other parliaments of Spain by the constitutional rule which required the consent of a majority of each order to every act of the Cortes. Thus the burgesses could not be outvoted by the nobles and the Church, as they could be elsewhere. Even in the 18th century the Navarrese successfully resisted Bourbon attempts to establish custom houses on the French frontier, dividing French from Spanish Navarre.

The institutions of Navarre which maintained their autonomy until the 19th century included the Cortes (The Three States, precursor to the Parliament of Navarre), Royal Council, Supreme Court and Diputacion del Reino. Similar institutions existed in the Crown of Aragon (in Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia) until the 18th century. The Spanish monarch was represented by a viceroy, who could object to the decisions made in the Navarrese context.

During that period Navarre enjoyed a special status within the Spanish monarchy; it had its own cortes, taxation system, and separate customs laws.

Later history and the end of the fueros

By the War of the Pyrenees and the Peninsular War, Navarre was in a deep crisis over the Spanish royal authority, involving the Spanish prime minister Manuel Godoy, who bitterly opposed the Basque charters, their autonomy, and maintained high duty exactions on the Ebro customs to abash the Navarrese, and the Basques altogether. The only way out the Navarrese found was an increased trade with France, which in turn spurred the importation of bourgeois, modern ideas. However, the progressive, enlightened bourgeois circles strong in Pamplona—and other Basque towns and cities like Donostia—were eventually quelled during the above wars.

After the French defeat, the only movement supporting the Navarrese self-government was Ferdinand VII. The king wielded the flag of the ancient régime, as opposed to the liberal Constitution of Cádiz (1812), which ignored the Navarrese and Basque fueros and any different identities in Spain, or the "Spains", as it was considered before the 19th century.

During the Napoleonic wars, many in Navarre took to the bush to avoid tax exactions and the military abuses over property and people during their expeditions, be their French, English, or Spanish. These parties sow the seeds to the later militias of the Carlist wars acting under different banners, Carlists most often, but also pro-fueros liberals. However, once the local, urban based enlightened bourgeois were suppressed by the Spanish authorities and backlashing at the French despotic rule during their occupation, the most staunchly Catholic rose to prominence in Navarre, coming under much clerical influence.

This, and the resentment felt at the loss of their autonomy when they were incorporated into Spain in 1833, account for the strong support given by many Navarrese to the Carlist cause. In 1833, Navarre and the whole Basque region in Spain became the chief stronghold of the Carlists, but in 1837 a Spanish Liberal, centralist constitution was proclaimed in Madrid, and Isabella II recognized as queen. Following the August 31st, 1839 armistice putting an end to the First Carlist War, Navarre remained in a shaky state.

Its separate status was acknowledged on the Act promulgated in October that year, but after arrival of Baldomero Espartero and the anti-fueros Progressives to office in Madrid, talks with Navarrese Liberal negotiators led to a near-assimilation of Navarre with the Spanish province. Navarre was not a kingdom anymore, but another Spanish province. In exchange for giving up self-government, the Navarrese got the Compromise Act (the Ley Paccionada) in 1841, a set of tax, administrative and other prerogatives, conjuring up an idea of 'compromise between two equal sides', and not a granted charter.

Province of Spain

Following the 1839–1841 treaties, conflict with Madrid's central government over Navarre's agreed administrative and fiscal idiosyncrasies contributed to the Third Carlist War, largely centred in the Basque districts (over in 1876). A myriad of parties and factions emerged in Navarre demanding different degrees of restoration of native institutions and laws. Catholicism and traditionalism became major driving forces behind Navarre politics.

The Church in Navarre became a mainstay of the reactionary Spanish Nationalist uprising against the 2nd Spanish Republic (1936). The figure of progressives and inconvenient dissidents exterminated across Navarre is estimated at around 3,000 in the period immediately after the successful military uprising (July 1936). As a reward for its support in the Spanish Civil War (Navarre sided for the most part with the military uprising), Franco allowed Navarre, as it happened with Álava, to maintain during his dictatorship some prerogatives reminiscent of the ancient Navarrese liberties. Navarre's specific status during Franco's regime led to the present-day Chartered Community of Navarre during the Spanish transition to democracy (the so-called Amejoramiento, 1982).

Territory today

The territory formerly known as Navarre now belongs to two nations, Spain and France, depending on whether it lies south or north of the Western Pyrenees. The Basque language is still spoken in most of the provinces. Today, Navarre is an autonomous community of Spain and Basse-Navarre is part of France's Pyrénées-Atlantiques département. Other former Navarrese territories belong now to several autonomous communities of Spain: the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, La Rioja, Aragon, and Castile and León.

See also

- Chartered Community of Navarre (modern)

- List of Navarrese monarchs

- Kings of Navarre family tree

- Court officials of the Kingdom of Navarre

- Basque Country (historical territory)

- Basque and Pyrenean Fueros

- History of the Basque people

- Vascones

Historic languages of the Kingdom of Navarre (824–1841):

- Basque, natural language in most of the realm except for the southern plains (Ribera), 824–1841

- Navarro-Aragonese, natural language along the Ebro, in the south-east, some boroughs, and status language, 10–15th century

- Occitan, natural language in some boroughs, status language, 11–14th century

- Castilian Romance/Spanish, natural language in southern and increasingly central areas and many urban centres substituting Basque, status language, 15th century-1841

- Gascon, written language in Lower Navarre and limited geographical and social contexts, 1305–1790

- Arabic, language of the Muslim communities remaining in southern areas after the conquest of Tudela in 1118, as well as Muslim liturgy language, 824–14th century and 824–early 16th century respectively

- French, status language increasingly replacing Gascon (Béarnese) in administration and politics, 1624–1790

- Erromintxela, language used by the native Romani communities especially in hilly areas, 15th century-1841

- Hebrew, religious and written language in Jewish communities located in certain urban centres, 10th century-1512

- Latin, Christian Catholic liturgy language and formal language in written scripts increasingly replaced by other Romance languages, 824–1841

Notes

- 1 2 3 Estibaliz Amorrortu, Basque Sociolinguistics: Language, Society, and Culture, (University of Nevada Press, 2003), 14 note5.

- ↑ R. L. Trask, The History of Basque, (Routledge, 2014), 427.

- ↑ Harvey, L.P. (1996). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. Chicago: Chicago University Press. p. 124-125. ISBN 978-0-226-31964-3.

- ↑ Jurio, Jimeno (1995). Historia de Pamplona y de sus Lenguas. Tafalla: Txalaparta. pp. 82, 138, 175–177. ISBN 84-8136-017-1.

- ↑ Harvey, L.P. (1996). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. Chicago: Chicago University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-226-31964-3.

- ↑ Ciervide Martinena, Ricardo Javier (1980). "Toponimia navarra: historia y lengua". Fontes Linguae Vasconum (34): 90, 91, 102. Retrieved 2016-10-30.

- ↑ Trask, Robert.L. (1996). The History of Basque. New York: Routledge. p. 427. ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

- ↑ Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. pp. 140–141. ISBN 0631175652.

- 1 2 Bernardo Estornés Lasa's Spanish article on Navarra in the Auñamendi Entziklopedia (click on "NAVARRA – NAFARROA (NOMBRE Y EMBLEMAS)")

- ↑ Louis the Pious, Rene Poupardin, The Cambridge Medieval History: Germany and the Western Empire, Vol. III, ed. J.B.Bury, (Cambridge University Press, 1936), 8.

- ↑ Du nouveau sur le royaume de Pampelune au IXe siècle, Évariste Lévi-Provençal, Bulletin Hispanique, 1953, Volume 55, Issue 55-1, page 11; "Mais, en ce qui concerne le roi vascon Inigo Iniguez..."

- ↑ Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. p. 135. ISBN 0-631-17565-2.

- ↑ Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. p. 140. ISBN 0-631-17565-2.

- ↑ Trask, R.L. (1997). The%20History%20of%20Basque%20%20Inigo%2C%20like%20most%20of%20the%20population%20of%20Navarre%20was%20a%20Basque&f=false The history of Basque. New York, USA: Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

- 1 2 Roger Collins, Caliphs and Kings: Spain 796-1031, (Blackwell Publishing, 2012), 210-211.

- ↑ "Crónica Albeldense". Humanidades.cchs.csic.es. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ Urzainqui, Tomás; Olaizola, Juan Maria (1998). La Navarra marítima. Pamplona: Pamiela. p. 94. ISBN 84-7681-293-0.

- ↑ But not the inhabitatns of Peralta; the lingua navarrorum is attested as the Basque language.

- ↑ Urzainqui, Tomás; Olaizola, Juan Maria (1998). La Navarra marítima. Pamplona: Pamiela. p. 111. ISBN 84-7681-293-0.

- ↑ Urzainqui, Tomás; Olaizola, Juan Maria (1998). La Navarra marítima. Pamplona: Pamiela. p. 152. ISBN 84-7681-293-0.

- ↑ Urzainqui, Tomás; Olaizola, Juan Maria (1998). La Navarra marítima. Pamplona: Pamiela. p. 115. ISBN 84-7681-293-0.

- ↑ Urzainqui, Tomás; Olaizola, Juan Maria (1998). La Navarra marítima. Pamplona: Pamiela. p. 116. ISBN 84-7681-293-0.

- ↑ Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. p. 104. ISBN 0631175652.

References

- Ariqita y Lasa, Colección de documentos para la historia de Navarra (Pamplona, 1900)

- Azurmendi, Joxe: "Die Bedeutung der Sprache in Renaissance und Reformation und die Entstehung der baskischen Literatur im religiösen und politischen Konfliktgebiet zwischen Spanien und Frankreich" In: Wolfgang W. Moelleken (Herausgeber), Peter J. Weber (Herausgeber): Neue Forschungsarbeiten zur Kontaktlinguistik, Bonn: Dümmler, 1997. ISBN 978-3537864192

- Bascle de Lagreze, La Navarre française (Paris, 1881)

- Blade, Les Vascons espagnols (Agen, 1891)

- Pierre Boissonade, Histoire de la reunion de la Navarre à la Castille (Paris, 1893)

- Chappuys, Histoire du royaume de Navarre (Paris, 1590; 1616)

- Favyn, Histoire de Navarre (Paris, 1612)

- Ferreras, La Historia de España (Madrid, 1700–27)

- Galland, Memoires sur la Navarre (Paris, 1648)

- Idem, Annales del reino de Navarra (5 vols., Pamplona, 1684–95; 12 vols., Tolosa, 1890–92)

- Idem, Diccionario de las antigüedades de Nayanna (Pamplona, 1840–43)

- Idem, Historia compendiada del reino de Navarra (S. Sebastián, 1832)

- Jaurgain, La Vasconie (Pau, 1898)

- de Marca, Histoire de Béarn (Paris, 1640)

- Moret, Investigationes históricas del reino de Navarra (Pamplona, 1655)

- Monreal, Gregorio; Jimeno, Roldan (2012). Conquista e Incorporación de Navarra a Castilla. Pamplona-Iruña: Pamiela. ISBN 978-84-7681-736-0.

- Oihenart, Notitia utriusque Vasconiae (Paris, 1656)

- Sorauren, Mikel. Historia de Navarra, el estado vasco. Pamiela, 1999. ISBN 84-7681-299-X

- Risco, La Vasconia en España Sagrada, XXXII (Madrid, 1779)

- Ruano Prieto, Anexión del Reino de Navarra en tiempo del Rey Católico (Madrid, 1899)

- Urzaniqui, Tomás, and de Olaizola, Juan María. La Navarra marítima. Pamiela, 1998. ISBN 84-7681-293-0

- Urzainqui, Tomas; Esarte, Pello; García Manzanal, Alberto; Sagredo, Iñaki; Sagredo, Iñaki; Sagredo, Iñaki; Del Castillo, Eneko; Monjo, Emilio; Ruiz de Pablos, Francisco; Guerra Viscarret, Pello; Lartiga, Halip; Lavin, Josu; Ercilla, Manuel (2013). La Conquista de Navarra y la Reforma Europea. Pamplona-Iruña: Pamiela. ISBN 978-84-7681-803-9.

- Yanguas y Miranda, Crónica de los reyes de Navarra (Pamplona, 1843)

External links

- "Navarre" Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911

- Medieval History of Navarre Genealogy

Coordinates: 42°49′01″N 1°38′34″W / 42.81694°N 1.64278°W