Egyptology

Egyptology (from Egypt and Greek -λογία, -logia. Arabic: علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious practices in the 4th century AD. A practitioner of the discipline is an "Egyptologist". In Europe, particularly on the Continent, Egyptology is primarily regarded as being a philological discipline, while in North America it is often regarded as a branch of archaeology.

History

The first explorers

The first explorers were the ancient Egyptians themselves. Thutmose IV restored the Sphinx and had the dream that inspired his restoration carved on the famous Dream Stele. Less than two centuries later, Prince Khaemweset, fourth son of Ramesses II, is famed for identifying and restoring historic buildings, tombs and temples including the pyramid.[2]

Graeco-Roman Period

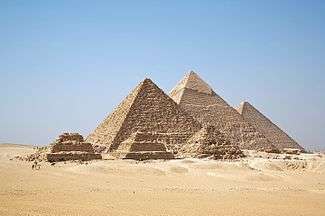

Some of the first historical accounts of Egypt were given by Herodotus, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus and the largely lost work of Manetho, an Egyptian priest, during the reign of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II in the 3rd century BC. The Ptolemies were much interested in the work of the ancient Egyptians, and many of the Egyptian monuments, including the pyramids, were restored by them (although they built many new temples in the Egyptian style). The Romans too carried out restoration work in this most ancient of lands.

Middle Ages

Throughout the Middle Ages travelers on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land would occasionally deviate to visit sites within Egypt, which would include Cairo and its environs, where the Holy Family was thought to have fled, and the great Pyramids, which were thought to be Joseph's Granaries, built by the Hebrew patriarch to store grain during the years of plenty. A number of their accounts (Itineraria) have survived and offer insights as to conditions in their respective time periods.[3]

Development of the field

Muslim scholars

Abdul Latif al-Baghdadi, a teacher at Cairo's Al-Azhar University in the 13th century, wrote detailed descriptions on ancient Egyptian monuments.[4] Similarly, the 15th-century Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi wrote detailed accounts of Egyptian antiquities.

European explorers

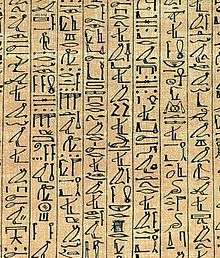

European exploration and travel writings of ancient Egypt commenced from the 13th century onward, with only occasional detours into a more scientific approach, notably by Claude Sicard, Benoît de Maillet, Frederic Louis Norden and Richard Pococke. In the early 17th century, John Greaves measured the pyramids, having inspected the broken Obelisk of Domitian in Rome, then destined for the Earl of Arundel's collection in London.[5] He went on to publish the illustrated Pyramidographia in 1646, while the Jesuit scientist-priest Athanasius Kircher was perhaps the first to hint at the phonetic importance of Egyptian hieroglyphs, demonstrating Coptic as a vestige of early Egyptian, for which he is considered a "founder" of Egyptology.[6] In the late 18th century, with Napoleon's scholars' recording of Egyptian flora, fauna and history (published as Description de l'Egypte), the study of many aspects of ancient Egypt became more scientifically oriented. The British captured Egypt from the French and gained the Rosetta Stone. Modern Egyptology is generally perceived as beginning about 1822.

Modern Egyptology

Egyptology's modern history begins with the invasion of Egypt by Napoleon Bonaparte. The subsequent publication of Description de l'Égypte between 1809 and 1829 made numerous ancient Egyptian source materials available to Europeans for the first time.[7] Jean-François Champollion, Thomas Young and Ippolito Rosellini were some of the first Egyptologists of wide acclaim. The German Karl Richard Lepsius was an early participant in the investigations of Egypt; mapping, excavating, and recording several sites. Champollion announced his general decipherment of the system of Egyptian hieroglyphics for the first time, employing the Rosetta Stone as his primary aid. The Stone's decipherment was a very important development of Egyptology. With subsequently ever-increasing knowledge of Egyptian writing and language, the study of Ancient Egyptian civilization was able to proceed with greater academic rigour and with all the added impetus that comprehension of the written sources was able to engender. Egyptology became more professional via work of William Matthew Flinders Petrie, among others. Petrie introduced techniques of field preservation, recording, and excavating. Howard Carter's expedition brought much acclaim to the field of Egyptology. Many highly educated amateurs now also travelled to Egypt, however, including women such as Harriet Martineau and Florence Nightingale, who both left philosophical accounts of their travels, which revealed learned familiarity with all the latest European Egyptology.[8]

A tradition of collecting objets-orientales (also Mediterranean (Roman and Greek) passed from Jean-Martin Charcot to Sigmund Freud.[9][10]

In the modern era, the Ministry of State for Antiquities[11] controls excavation permits for Egyptologists to conduct their work. The field can now use geophysical methods and other applications of modern sensing techniques to further Egyptology.

Egyptology as an academic discipline

Egyptology was established as an academic discipline through the research of Emmanuel de Rougé in France, Samuel Birch in England, and Heinrich Brugsch in Germany. In 1880, Flinders Petrie, another British Egyptologist, revolutionized the field of archaeology through controlled and scientifically recorded excavations. Petrie's work determined that Egyptian culture dated back as early as 4500 BCE. The British Egypt Exploration Fund founded in 1882 and other Egyptologists promoted Petrie's methods. Other scholars worked on producing a hieroglyphic dictionary, developing a Demotic lexicon, and establishing an outline of ancient Egyptian history.[7]

In the United States, the founding of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago and the expedition of James Henry Breasted to Egypt and Nubia established Egyptology as a legitimate field of study. In 1924, Breasted also started the Epigraphic Survey with the goal of making and publishing accurate copies of monuments. In the late 19th and early 20th century the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the University of Pennsylvania; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Brooklyn Institute of Fine Arts; and the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University also conducted excavations in Egypt, expanding American collections.[7]

Some universities and colleges offer degrees in Egyptology. In the United States, these include the University of Chicago, Brown University, New York University, Yale University and Indiana University - Bloomington. There are also many programs in the United Kingdom, including those at the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge, Swansea University, the University of Liverpool, and the University of London. German institutions have remained prominent in Egyptology and have produced many of the field's most well-respected experts.[12] The Czechoslovak (later Czech) Egyptological Institute at Charles University was founded in Prague by František Lexa in 1958.

Societies for Egyptology include:

- The Society for the Study of Ancient Egypt[13]

- The Society for the Study of Ancient Egyptian Antiquities, Canada[14]

- Sussex Egyptology Society Online[15]

- Egypt Exploration Society[16]

According to the UCLA the standard text that scholars referenced for studies of Egyptology was for three decades or more, the Lexicon der Ägyptologie. The first volume published in 1975 (containing largely German-language articles, with a few in English and French).[17]

See also

- Artifact (archaeology)

- Cultural tourism in Egypt

- Egyptomania

- Excavation (archaeology)

- List of Egyptologists

Other related disciplines not mentioned in the article:

- Anthropology

- Archaeoastronomy

- Architecture

- Art history

- Assyriology

- Biblical studies

- Chronology

- Epigraphy

- Ethnoarchaeology

- Iranology

- Language studies

- Philology

- Social history

Notes and references

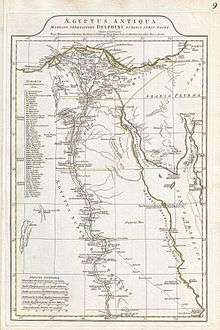

- ↑ Thompson 2015, p. 85: “Ancient and modern Egypt became easier to conceptualize because of the prolific French cartographer Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville (1697–1782). The greatest mapmaker of his age, Bourguignon d’Anville also had a special interest in ancient geography, one that he wrote would not permit me to neglect Egypt, this country so celebrated in antiquity." Instead of copying older maps and blindly replicating their errors and speculations as had long been the practice he sought reliable data and was content to leave spaces blank rather than fill them with conjectural features. He had no firsthand experience with Egypt, but he carefully pored over every available source modern ancient and Arab as he explained in his ‘’Memoires sur l’Egypte ancienne et moderne’’ (1766). Bourguignon d’Anville’s map of Egypt allowed readers to see the relationship of ancient and modern sites much more clearly than before. It continued in use well into the nineteenth century. Although the cartographers of Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition made a more accurate map, it was declared a state secret and Bourguignon d’Anville’s map was printed in its place in the great ‘’Description de l’Egypte.’’”

- ↑ © Greg Reeder retrieved GMT23:48.3.9.2010

- ↑ Nicole Chareyron, Pilgrims to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 127–97. [ISBN 0231132301]

- ↑ Dr. Okasha El Daly (2005), Egyptology: The Missing Millennium: Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings, UCL Press, ISBN 1-84472-063-2. (cf. Arabic Study of Ancient Egypt, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.)

- ↑ Edward Chaney, "Roma Britannica and the Cultural Memory of Egypt: Lord Arundel and the Obelisk of Domitian", in Roma Britannica: Art Patronage and Cultural Exchange in Eighteenth-Century Rome, eds. D. Marshall, K. Wolfe and S. Russell, British School at Rome, 2011, pp. 147–70.

- ↑ Woods, Thomas. How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization, p 4 & 109. (Washington, DC: Regenery, 2005); ISBN 0-89526-038-7.

- 1 2 3 "Egyptology" (PDF). Saylor.org. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ Edward Chaney, 'Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution', in: Sites of Exchange: European Crossroads and Faultlines, eds. M. Ascari and A. Corrado (Rodopi, Amsterdam and New York,2006), 39–74.

- ↑ Edited by Maurizio Ascari and Adriana Corrado-essay of Edward Chaney pages 39–40 retrieved 17:02GMT 3.10.11

- ↑ FREUD MUSEUM LONDON retrieved 17:06GMT 3.10.11

- ↑ The Ministry of State for Antiquities retrieved 18:55GMT 3.10.11

- ↑ "Where to Study Egyptology". Guardian's Egypt. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ The Society for the Study of Ancient Egypt 20:53GMT.14.3.2008

- ↑ The Society for the Study of Ancient Egyptian Antiquities, Canada 20:58GMT 3.8.2008

- ↑ Sussex Egyptology Society Online retrieved GMT21:27.26.2.2006

- ↑ Egypt Exploration Society retrieved 16:36GMT 3.10.11

- ↑ Angeles Project Development Information;Homepage retrieved 17:47GMT 3.10.11

Further reading

- David, Rosalie. Religion and magic in ancient Egypt. Penguin Books, 2002. ISBN 0-14-026252-0

- Chaney, Edward. 'Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution', in: Sites of Exchange: European Crossroads and Faultlines, eds. M. Ascari and A. Corrado (Rodopi, Amsterdam and New York,2006), 39–74.

- Chaney, Edward. "Roma Britannica and the Cultural Memory of Egypt: Lord Arundel and the Obelisk of Domitian", in Roma Britannica: Art Patronage and Cultural Exchange in Eighteenth-Century Rome, eds. D. Marshall, K. Wolfe and S. Russell, British School at Rome, 2011, pp. 147–70.

- Hill, Marsha (2007). Gifts for the gods: images from Egyptian temples. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588392312.

- Jacq, Christian. Magic and mystery in ancient Egypt. Souvenir Press, 1998. ISBN 0-285-63462-3

- Manley, Bill (ed.). The Seventy Great Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05123-2

- Mertz, Barbara. Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt. Dodd Mead, 1978. ISBN 0-396-07575-4

- Mertz, Barbara. Temples, Tombs and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt. Bedrick, 1990. ISBN 0-87226-223-5

- Mysteries of Egypt. National Geographic Society, 1999. ISBN 0-7922-9752-0

- Thompson, Jason (2015). Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology: 1: From Antiquity to 1881. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-61797-636-0.

- Jason Thompson (2016). Wonderful Things, Volume 2: A History of Egyptology: 2: The Golden Age: 1881–1914. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-692-1.

External links

| Look up Egyptology or Egyptologist in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "North African Archaeology". ANTIQUITYOFMAN.COM: Anatomical and Behavioural Evolution. Retrieved October 15, 2006. Sections, all with content relevant to antiquity: Articles; Books, journals and external resources; Expeditions and fieldwork opportunities; and Professional organizations)

- "Egyptologists' Electronic Forum (EEF), version 64". Egyptological Societies and Institutes. September 13, 2015. List shows Egyptology societies and Institutes

- Egyptology at DMOZ

- "Egyptology Books and Articles in PDF online". The University of Memphis Institute of Egyptian Art and Archaeology. March 6, 2015.

- "Egyptology collection". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- "A key to the translation exercises in Sir Alan Gardiner's Egyptian Grammar, Electronic publications, Egyptological databases, Dictionaries and lexicography, Useful Web sites & Main libraries with Egyptological holdings". Griffiths Institute, OXFORD UNIVERSITY.

- Hawass, Zahi & Brock, Lyla Pinch (Editors) (2000). "Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century Proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists". American University in Cairo Press. Cairo. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- "Rare Books and Special Collections Digital Library Underwood & Underwood Egypt Stereoviews Collection". American University in Cairo.

- "Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague". Czech Institute of Egyptology.