Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus

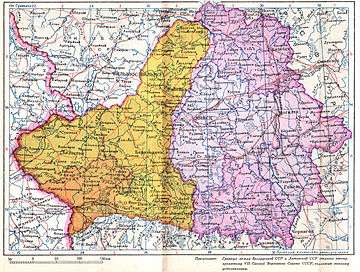

Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus, which took place on October 22, 1939, were an attempt to legitimize the annexation of the Second Polish Republic by the Soviet Union following the September 17 Soviet invasion of Poland in accordance with the secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Only one month after the eastern territories of Poland were occupied by the Red Army, the Soviet secret police and military led by the Party officials staged the local elections in an atmosphere of state terror.[1] The referendum was rigged. The ballot envelopes were numbered and often handed over already sealed. By design, the candidates were unknown to their constituencies which were brought to the voting stations by armed militias.[1] The results were to become the official legitimization of the Soviet takeover of what is known today as the West Belarus and the Western Ukraine.[2] Consequently, both Assemblies voted for incorporation of all formerly Polish voivodeships into the Soviet Union.[3]

Background

On September 17, 1939, the Red Army invaded eastern Poland, facing weak resistance of units of the Border Defence Corps, scattered along the border. The Soviets moved quickly westwards, towards the line of partition of Poland, established earlier, during Soviet - Nazi negotiations. After the invasion, the Second Polish Republic and Soviet Union found themselves de facto at war with each other, and Soviet authorities took advantage of the situation, to make permanent changes of the legal order of occupied territories. Their activities broke Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Convention, which states: "The authority of the legitimate power having in fact passed into the hands of the occupant, the latter shall take all the measures in his power to restore, and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country".[4]

As soon as the Soviets occupied Polish areas, they began organizing local governments and units of administrative division, whose borders roughly corresponded with the borders of interbellum voivodeships. Temporary authorities were made of NKVD agents, Red Army officers, local laborers, and left-wing intelligentsia. Their task was to organize the so-called workers guard in the municipal centers, and farmers committees, which were preparing land reform. Soon afterwards, these temporary authorities were replaced with Soviet-style administration and Communist Party of the Soviet Union committees. Also, NKVD apparatus took over military tasks.

After signing the German-Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty (28 September 1939), which established the mutual border along the Bug River, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union decided on October 1, 1939, that People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and West Belarus should be called in Lviv (for Western Ukraine), and Belastok (for West Belarus). The task of these bodies was to urge Moscow to incorporate the land into the Soviet Union. Furthermore, a People's Assembly of Poland had been planned, for the areas around Lublin, Siedlce, and Łomża, which were to have been annexed by the Soviets.[5] However, after some changes in the Nazi - Soviet Pact (see German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation), those areas were occupied by Nazi Germany.

The election

The electoral campaign began on October 7, 1939, and from the beginning, was supervised by the NKVD troops. The campaign itself took place in an atmosphere of state terror, with mass arrests, and uniformed NKVD agents present at all polling stations.[6] All candidates had been designated by the party's local peasants and workers' committees based on instructions from Moscow. It was not possible to vote for anybody else. Soviet banners and posters were seen everywhere, people were gathered to listen to propaganda slogans, and frequently, citizens were told that if they did not participate, they would be fired, arrested, and event sent to Siberia. Electoral meetings were very short. Participants were asked "who was against" the candidate offered; frightened people would not raise their hands, and then the meeting was closed.[6] On October 11, in article published in Pravda, Soviet propaganda pointed out the issues to be solved by the Western Ukraine's Assembly. These were: establishment of Soviet authority, unification of Western Ukraine with Soviet Ukraine, confiscation of estates, and nationalization of banks and industrial properties.[7] There were instances when local Polish Communists, especially in Western Belarus, tried to designate their own candidates, but these attempts were immediately dismissed by the party officials.

Historian Rafal Wnuk, author of the book During the First Soviet,[8] described the election in the city of Lviv. According to his research, on the day of the election, the city was flooded with the Soviet propaganda posters. At the polling stations, the inhabitants were able to purchase alcohol products and foods otherwise not available on the market. In some cases, people were brought by force. As Bronislawa Stachowicz from Lviv recalled:

I was forced to vote, taken from our home only in slippers and a bathrobe. I was escorted by two militiamen and an NKVD agent, who did not let me put on my coat. My mother, brother, and sister were also forced to vote. [5]

At all voting stations, there were uniformed militia or soldiers, and names were checked on a list. Voting was monitored to such a degree that in some places people were given envelopes which had been already sealed, and told to drop them in the box.[6] Both the campaign and the election were presented as a "great holiday of the freed people". A Polish-language newspaper "Wolna Łomża" ("Free Łomża") wrote on October 22 that "suppressed by the Polish masters masses of Western Belarus had been waiting for this day [October 22] for almost twenty years". Another newspaper, "Nowe Zycie" ("New Life") wrote: "Never before has the nation enjoyed so much freedom as now, given by the Red Army".

The results of the election show the efficiency of the Stalinist state. According to the official data, in Western Ukraine, 93% voters took part in it,[9] and in Western Belarus - 96%.[10] Party candidates garnered more than 90% of the popular vote. However, in some districts (11 in Ukraine, and 2 in Belarus), the candidates were so unpopular, that they got less than half of the votes, and it was necessary to organize a second election. It must also be noted, that among those eligible to vote, were soldiers of the Red Army, who had invaded these provinces just five weeks before. Polish historians noted some cases of civil disobedience, which took place despite widespread terror. In Białystok, people would put in cards with slogans such as "Long live Poland, Białystok is not Belarus". In Hrodna, slogans on the walls were painted, which said "Down with the Bolsheviks, long live Poland", and in Pinsk, high school students handed leaflets stating: "Long live Poland, down with Communists".

People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus

Deputies, elected in the rigged election, formed two legislative bodies - the People's Assembly of Western Ukraine, and the People's Assembly of Western Belarus. Meetings of these bodies took place respectively on 26–28 October 1939 in Lviv, and 28–30 October in Białystok. The Lviv meeting was opened by Ukrainian philology professor Kyryl Studynsky, and the Białystok meeting - by Belarusian peasant Stepan Strug. Out of 926 members of the People's Assembly of Western Belarus, there were 621 Belarusians, 127 Poles, 72 Jews, 43 Russians, 53 Ukrainians, and 10 from other nationalities.[5] The Western Ukraine's People's Assembly had 1,482 members, out of which Poles made only 3%.[11] Both bodies supported the establishment of Soviet rule over the occupied territories, and issued official requests to the Supreme Soviet, asking it for permission to join the already existing Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic and Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Also, all real estate of landowners, churches and state officials, was confiscated without compensation (including buildings and animals). Banks and larger factories were nationalized, and September 17 was established as an official holiday. Meetings of both Assemblies were based on criticism of interbellum Poland, describing "exterminational policies of White Polish occupiers, bloodsuckers and landowners", who suppressed "Ukrainian and Belarusian masses".[12] People's Assembly of Western Ukraine wrote an official letter, which was sent to the Belarusian Assembly. Among others, it said: "We were brothers in captivity and struggle against Polish masters. Now we have become brothers in freedom and happines. Great Red Army, fulfilling the wishes of the mighty Soviet nations, has come here and for centuries freed us, Western Ukrainians and Western Belarusians, from suppression of Polish landowners and capitalists"[13]

On November 1, the Supreme Soviet approved annexation of Western Ukraine, and on the next day, of Western Belarus. On November 14, the Supreme Soviet of Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic in Minsk officially annexed former territories of northeastern Poland, without the area of Wilno, which had been seized by Lithuania. On November 15, the Supreme Soviet of Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in Kiev, annexed former southeastern Poland. On November 29, the Supreme Soviet issued a decree upon which all inhabitants of Poland living in Western Ukraine and Western Belarus became citizens of the Soviet Union. This decision had a far-reaching consequences, because now, the NKVD apparatus had legal reasons to arrest members of prewar political parties of Poland, accusing them of anti-Soviet activity.[14] Furthermore, the Supreme Soviet's decree resulted in massive draft into the Red Army. Polish historian Rafal Wnuk estimates that 210 000 inhabitants of former eastern Poland, born in 1917, 1918, and 1919, ended up in the Red Army.[12] After official annexation of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus, both Assemblies were dissolved.

See also

- Soviet annexation of Western Ukraine, 1939–1940

- Occupation of the Baltic states

- German–Soviet military parade in Brest-Litovsk

- Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Soviet repressions of Polish citizens (1939–1946)

- Occupation of Poland (1939–1945)

- Territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union

References

- 1 2 Jan T. Gross (1997). Sovietisation of Poland's Eastern Territories. From Peace to War: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the World, 1939-1941. Berghahn Books. pp. 74–75. ISBN 1571818820. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ Jan Tomasz Gross (2002). Revolution from abroad. Princeton University Press. p. 71. ISBN 0-691-09603-1.

- ↑ Geoffrey Roberts (2006). Stalin's wars: from World War to Cold War, 1939-1953. Yale University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-300-11204-1.

- ↑ Laws of War : Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague IV); October 18, 1907.

- 1 2 3 P.D., Polish Radio online. "Wyborcza farsa w stylu ZSRS: 22 października 1939" [The electoral farce Soviet style: 22 October 1939]. Grzegorz Hryciuk, Polacy we Lwowie 1939 - 1944, Warszawa 2000 (in Polish). Archived from the original on July 15, 2009 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 Bernd Wegner (1997). From peace to war: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the world, 1939 – 1941. Berghahn Books. p. 74. ISBN 1-57181-882-0.

- ↑ Irena Grudzińska-Gross (1985). War Through Children's Eyes: The Soviet Occupation of Poland. Hoover Press. p. 251. ISBN 0-8179-7472-5.

- ↑ Rafał Wnuk (2007). Za Pierwszego Sovieta. Polska konspiracja na Kresach Wschodnich II Rzeczypospolitej (wrzesień 1939 - czerwiec 1941) [During the First Soviet. Polish underground in the Soviet-occupied eastern provinces of the Second Polish Republic]. Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN. ISBN 978-83-60464-47-2.

- ↑ Orest Subtelny (2000). Ukraine: a history. University of Toronto Press. p. 454. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- ↑ David R. Marples (1999). Belarus: a denationalized nation. Taylor & Francis. p. 13. ISBN 90-5702-343-1.

- ↑ Tomasz Bereza, Październik 1939 r. - początki sowietyzacji Kresów Wschodnich Rzeczypospolitej. Rzeszów's office of Institute of National Remembrance.

- 1 2 Rafał Wnuk, IPN Lublin. "Za pierwszego sowieta. Polska konspiracja na kresach wschodnich II RP (Wrzesień 1939 – Czerwiec 1941)". Book excerpts. Chapter I, from the Institute of National Remembrance (in Polish).

- ↑ "Głosujcie za przyłączeniem Zachodniej Białorusi do wielkiego Związku Radzieckiego" (in Polish).

- ↑ Przemysław Włodek, Adam Kulewski (2006). Lwów: przewodnik (in Polish). Oficyna Wydawnicza "Rewasz". p. 55. ISBN 83-89188-53-8.