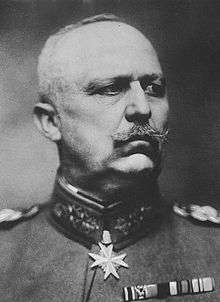

Erich Ludendorff

| Erich Ludendorff | |

|---|---|

General Erich Ludendorff | |

| Birth name | Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff |

| Born |

9 April 1865 Kruszewnia near Posen, Province of Posen, Kingdom of Prussia (now Poznań, Poland) |

| Died |

20 December 1937 (aged 72) Munich, Bavaria, Nazi Germany |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1883–1918 |

| Rank | General der Infanterie |

| Battles/wars |

World War I German Revolution |

| Awards |

Pour le Mérite Iron Cross First class |

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general, the victor of the Battle of Liège and the Battle of Tannenberg. From August 1916, his appointment as Quartermaster general (Erster Generalquartiermeister) made him the leader (along with Paul Hindenburg) of the German war efforts during World War I until his resignation in October 1918, just before the end of hostilities.[1][2]

After the war, Ludendorff became a prominent nationalist leader, and a promoter of the stab-in-the-back legend, which posited that the German loss in World War I was caused by the betrayal of the German Army by Marxists and Bolsheviks who were furthermore responsible for the disadvantageous settlement negotiated for Germany in the Versailles Treaty. He took part in the unsuccessful coup d’état with Wolfgang Kapp in 1920 and the Beer Hall Putsch of Adolf Hitler in 1923, and in 1925, he ran for the office of President of Germany against his former superior Hindenburg, whom he claimed had taken credit for Ludendorff's victories against Russia.[1][3]

From 1924 to 1928 he represented the German Völkisch Freedom Party in the German Parliament. Consistently pursuing a purely military line of thought, Ludendorff developed, after the war, the theory of “Total War,” which he published as Der Totale Krieg (The Total War) in 1935. In this work, he argued that the entire physical and moral forces of the nation should be mobilized, because, according to him, peace was merely an interval between wars.[4] Ludendorff was a recipient of the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross and the Pour le Mérite.

Early life

Ludendorff was born on 9 April 1865 in Kruszewnia near Posen, Province of Posen, Kingdom of Prussia (now Poznań County, Poland), the third of six children of August Wilhelm Ludendorff (1833–1905). His father was descended from Pomeranian merchants who had achieved the status of Junker, i.e. owner of a manor, and he held a commission in the reserve cavalry.

Erich's mother, Klara Jeanette Henriette von Tempelhoff (1840-1914), was the daughter of the noble but impoverished Friedrich August Napoleon von Tempelhoff (1804-1868) and his wife Jeannette Wilhelmine von Dziembowska (1816–1854), who came from a Germanized Polish landed family on the side of her father Stephan von Dziembowski (1779-1859). Through Dziembowski's wife Johanna Wilhelmine von Unruh (1793-1862), Erich was a remote descendant of the Counts of Dönhoff, the Dukes of Legnica and Brzeg and the Marquesses and Electors of Brandenburg.

He had a stable and comfortable childhood, growing up on their small family farm. Erich received his early schooling from his maternal aunt and had a gift for mathematics,[5] as did his younger brother Hans who became a distinguished astronomer. He passed the entrance exam for the Cadet School at Plön with distinction,[5] he was put in a class two years ahead of his age group, and thereafter he was consistently first in his class. (The famous World War II General Heinz Guderian attended the same Cadet School, which produced many well-trained German officers.) Ludendorff's education continued at the Hauptkadettenschule at Groß-Lichterfelde near Berlin through 1882.[6]

At age 45 "... the 'old sinner', as he liked to hear himself called ..." [7] married the daughter of a wealthy factory owner, Margarethe née Schmidt (1875–1936). They met in a rainstorm when he offered his umbrella. She divorced to marry him, bringing three stepsons and a stepdaughter.[6] Their marriage pleased both families and he was devoted to his stepchildren.

Prewar military career

In 1885, Ludendorff was commissioned as a subaltern into the 57th Infantry Regiment, then at Wesel. Over the next eight years, he was promoted to lieutenant and saw further service in the 2nd Marine Battalion, based at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven, and in the 8th Grenadier Guards at Frankfurt on the Oder. His service reports reveal the highest praise, with frequent commendations. In 1893, he entered the War Academy, where the commandant, General Meckel, recommended him to the General Staff, to which he was appointed in 1894. He rose rapidly and was a senior staff officer at the headquarters of V Corps from 1902 to 1904.

Next he joined the Great General Staff in Berlin, which was commanded by Alfred von Schlieffen. Ludendorff directed the Second or Mobilization Section from 1904–13. Soon he was joined by Max Bauer, a brilliant artillery officer, who became a close friend. By 1911, Ludendorff was a full colonel. His section was responsible for writing the mass of detailed orders needed to bring the mobilized troops into position to implement the Schlieffen Plan. For this they covertly surveyed frontier fortifications in Russia, France and Belgium. For instance, in 1911 Ludendorff visited the key Belgian fortress city of Liège.

Deputies of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which became the largest party in the Reichstag after the German federal elections of 1912, seldom gave priority to army expenditures, whether to build up its reserves or to fund advanced weaponry such as Krupp's siege cannons. Instead, they preferred to concentrate military spending on the Imperial German Navy. Ludendorff's calculations showed that to properly implement the Schlieffen plan the Army lacked six corps.

Members of the General Staff were instructed to keep out of politics and the public eye,[8] but Ludendorff shrugged off such restrictions. With a retired general, August Keim, and the head of the Pan-German League, Heinrich Class, he vigorously lobbied the Reichstag for the additional men.[9] In 1913 funding was approved for four additional corps but Ludendorff was transferred to regimental duties as commander of the 39th (Lower Rhine) Fusiliers, stationed at Düsseldorf. "... I attributed the change partly for my having pressed for those three additional army corps."[10]

Barbara Tuchman characterizes Ludendorff in her book The Guns of August as Schlieffen’s devoted disciple who was a glutton for work and a man of granite character but who was deliberately friendless and forbidding and therefore remained little known or liked. It is true that as his wife testified, "Anyone who knows Ludendorff knows that he has not a spark of humor…“.[11] He was voluble nonetheless, although he shunned small talk. John Lee,[12] states that while Ludendorff was with his Fusiliers, "he became the perfect regimental commander ... the younger officers came to adore him." His adjutant, Wilhelm Breucker, became a devoted lifelong friend. Even a brief account of his life shows the importance of his friends.

Start of World War I

At the outbreak of war in the summer of 1914 Ludendorff was appointed Deputy Chief of Staff to the German Second Army under General Karl von Bülow. His assignment largely due to his previous work investigating defenses of Liège, Belgium. At the beginning of the Battle of Liège Ludendorff was an observer with the 14th Brigade, which was to infiltrate the city at night and secure the bridges before they could be destroyed. The brigade commander was killed on 5 August, so Ludendorff led the successful assault to occupy the city and its citadel. In the following days, two of the forts guarding the city were taken by desperate frontal infantry attacks, while the remaining forts were smashed by huge Krupp 42-cm and Austro-Hungarian Skoda 30-cm howitzers. By 16 August, all the forts around Liège had fallen, allowing the German First Army to advance. As the victor of Liège, Ludendorf was awarded Germany's highest military decoration for gallantry, the Pour le Mérite, presented by Kaiser Wilhelm II himself on 22 August.[13]

The Eastern Front

German mobilization earmarked a single army, the Eighth, to defend their eastern frontier. Two Russian armies invaded East Prussia earlier than expected, the Eighth Army commanders panicked and were fired by OHL, Oberste Heeresleitung, German Supreme Headquarters. OHL assigned Ludendorff as the new chief of staff, while the War Cabinet chose a retired general, Paul von Hindenburg, as commander. They first met on their private train heading east. They agreed that they must annihilate the nearest Russian army before they tackled the second. Nine days later the Eighth Army surrounded most of a Russian army at Tannenberg, taking 92,000 prisoners in one of the great victories in German history. Twice during the battle Ludendorff wanted to break off, fearing that the second Russian army was about to strike their rear, but Hindenburg held firm.

Then they turned on the second invading army in the Battle of the Masurian Lakes; it fled with heavy losses to escape encirclement. During the rest of 1914, commanding an Army Group, they staved off the projected invasion of German Silesia by dexterously moving their outnumbered forces into Russian Poland, fighting the battle of the Vistula River, which ended with a brilliantly executed withdrawal during which they destroyed the Polish railway lines and bridges needed for an invasion. When the Russians had repaired most of the damage the Germans struck their flank in the battle of Łódź, where they almost surrounded another Russian Army. Masters of surprise and deft maneuver, they argued that if properly reinforced they could trap the entire Russian army in Poland. During the winter of 1914-15 they lobbied passionately for this strategy, but were rebuffed by OHL

Early in 1915 they surprised the Russian army that still held a toehold in East Prussia by attacking in a snowstorm and surrounding it in the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes. OHL then transferred Ludendorff, but Hindenburg’s personal plea to the Kaiser reunited them. Erich von Falkenhayn, supreme commander at OHL, came east to attack the flank of the Russian army that was pushing through the Carpathian passes towards Hungary. Employing overwhelming artillery, the Germans and Austro-Hungarians broke through the line between Gorlice and Tarnów and kept pushing until the Russians were driven out of most of Galicia, the Austro-Hungarian southern part of partitioned Poland. During this advance Falkenhayn rejected schemes to try to cut off the Russians in Poland, preferring direct frontal attacks. Outgunned, during the summer of 1915 the Russian commander Grand Duke Nicholas shortened his lines by withdrawing from most of Poland, destroying railroads, bridges, and many buildings while driving 743,000 Poles, 350,000 Jews, 300,000 Lithuanians and 250,000 Latvians into Russia.[14]

During the winter of 1915-1916 Ludendorff's headquarters was in Kaunas. They were responsible for newly conquered territory in present-day Lithuania, western Latvia, and north eastern Poland, an area almost the size of France—suddenly without a government. Ludendorff was happy to fill the void. A defensive trench line was surveyed, dug and manned; the troops were settled into winter billets and their other needs met, including libraries and German newspapers. Demolished infrastructure was rebuilt. Workshops refurbished captured weapons. Selected older soldiers became policemen, a challenging job because few could speak the languages of the disgruntled inhabitants, so Yiddish speaking Jews were used as translators. Qualified soldiers and German civilian experts officiated over civil life, reanimating agriculture and industry to provide goods for Germany and preparing for future colonization.[15] [16]

On 16 March 1916 the Russians, now with adequate supplies of cannons and shells, attacked parts of the new German defenses, intending to penetrate at two points and then to pocket the defenders. They attacked almost daily until the end of the month, but the Lake Naroch Offensive failed, “choked in swamp and blood”,[17] The Russians did better attacking the Austro-Hungarians in the south. The Brusilov Offensive cracked their lines with surprise hurricane bombardments followed by well-schooled assault troops probing for weak spots. The breakthrough was finally stemmed by Austro-Hungarian troops recalled from Italy stiffened with German advisers and reserves. In July Russian attacks on the Germans in the north were beaten back. On 27 July 1916 Hindenburg was given command of all troops on the Eastern Front from the Baltic to Brody in the Ukraine. They visited their new command on a special train, and then set up headquarters in Brest Litovsk. By August 1916 their front was holding everywhere.

The supreme command

In the West in 1916 the Germans attacked unsuccessfully at Verdun and soon were reeling under British and French blows along the Somme. Ludendorff’s friends at OHL, led by Max Bauer, lobbied for him relentlessly. The balance was tipped when Romania entered the war, thrusting into Hungary. Falkenhayn was replaced as Chief of the General Staff by Field Marshal Hindenburg on 29 August 1916. Ludendorff was his chief of staff as first Quartermaster general, with the stipulation that he would have joint responsibility.[18] He was promoted to General of the Infantry. Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg warned the War Cabinet: “You don’t know Ludendorff, who is only great at a time of success. If things go badly he loses his nerve.” [19] Their first concern was the sizable Romanian Army, so troops sent from the Western Front checked Romanian and Russian incursions into Hungary. Then Romania was invaded from the south by German, Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian, and Ottoman troops commanded by August von Mackensen and from the north by a German and Austro-Hungarian army commanded by Falkenhayn. Bucharest fell in December 1916. According to Mackensen Ludendorff’s distant management consisted of “… floods of telegrams, as superfluous as they were offensive. “ [20]

When sure that the Romanians would be defeated OHL moved west, retaining the previous staff except for the operations officer, blamed for Verdun. They toured the Western Front meeting —and evaluating— commanders, learning about their problems and soliciting their opinions. At each meeting Ludendorff did most of the commander’s talking. There would be no further attacks at Verdun and the Somme would be defended by revised tactics that exposed fewer men to British shells. A new backup defensive line would be built, like the one they had constructed in the east. The Allies called the new fortifications the Hindenburg Line. The German goal was victory, which they defined as a Germany with extended borders that could be more easily defended in the next war.

Hindenburg was given titular command over all of the forces of the Central Powers. Ludendorff’s hand was everywhere. Every day he was on the telephone with the staffs of their armies and the Army was deluged with "Ludendorff's paper barrage" [21] of orders, instructions and demands for information. His finger extended into every aspect of the German war effort. He issued the two daily communiques, and often met with the newspaper and newsreel reporters. Before long the public idolized him as their Army’s brain.

The Home Front

Ludendorff had a goal: “One thing was certain— the power must be in my hands." [22] As stipulated by the Constitution of the German Empire the government was run by civil servants appointed by the Kaiser. Confident that army officers were superior to civilians, OHL volunteered to oversee the economy: procurement, raw materials, labor, and food.[23] Bauer, with his industrialist friends, knew exactly what should be done, beginning by setting overambitious targets for military production in what they called the Hindenburg Program. Ludendorff enthusiastically participated in meetings on economic policy— loudly, sometimes pummeling the table with his fists. Implementation of the Program was assigned to General Groener, a staff officer who had directed the Field Railway Service effectively. His office was in the War Ministry, not in OHLas Ludendorff had wanted. Therefore, he assigned staff officers to most of the government ministries, so he knew what was going on and could press his demands.

War industry’s major problem was the scarcity of skilled workers, therefore 125,000 men were released from the armed forces and trained workers were no longer conscripted. OHL wanted to enroll most German men and women into national service, but the Reichstag legislated that only males 17-60 were subject to “patriotic service” and refused to bind war workers to their jobs.[24] Groener realized that they needed the support of the workers, so he insisted that union representatives be included on industrial dispute boards. He also advocated an excess profits tax. The industrialists were incensed. On 16 August 1917 Ludendorff telegraphed an order reassigning Groener to command the 33rd Infantry Division.[25] Overall, “Unable to control labour and unwilling to control industry, the army failed miserably... .” [26] To the public it seemed that that Ludendorff was running the nation as well as the war. According to Ludendorff, “… the authorities … represented me as a dictator … .” [27] He would not become Chancellor because the demands for running the war were too great.[28] The historian Frank B. Tipton argues that while not technically a dictator, Ludendorff was "unquestionably the most powerful man in Germany" in 1917–18.[29]

OHL did nothing to mitigate the food disaster: despite the blockade everyone could have been fed adequately, but supplies were not managed effectively or fairly.[30] In Spring 1918 half of all the meat, eggs and fruit consumed in Berlin were sold on the black market.[31]

National politics

The navy advocated unrestricted submarine warfare, which would surely bring the United States into the war. The Kaiser asked his commanders to listen to the warnings of his friend, the eminent chemist Walther Nernst, who knew America well. Ludendorff promptly ended the meeting, it was “… incompetent nonsense with which a civilian was wasting his time… “ .[32] Unrestricted submarine warfare began in February 1917, with OHL’s strong support. This fatal mistake reflected poor military judgment in uncritically accepting the Navy’s contention that there were no countermeasures, like convoying, and confident that the American armed forces were too feeble to fight effectively. Ultimately Germany was at war with 27 nations.

In the spring of 1917 the Reichstag passed a resolution for peace without annexations or indemnities. They would be content with the successful defensive war undertaken in 1914. OHL was unable to defeat the resolution or to have it substantially watered down. The commanders despised Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg as weak, so they forced his resignation by repeatedly threatening to resign themselves, despite the Kaiser's admonition that this was not their business. He was replaced by a minor functionary, Georg Michaelis, the food minister, who announced that he would deal with the resolution as “in his own fashion".[33] Despite this put-down, the Reichstag voted the financial credits needed for continuing the war.

Ludendorff insisted on the huge territorial losses forced on the Russians in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, even though this required that a million German soldiers remain in the east. During the peace negotiations with the Romanians his representative kept demanding the economic concessions coveted by the German industrialists. The commanders kept blocking attempts to frame a plausible peace offer to the western powers by insisting on borders expanded for future defense. Ludendorff regarded the Germans as the “master race” [34] and after victory planned to settle ex-soldiers in the Baltic states and in Alsace Lorraine, where they would take over property seized from the French.[35] One after another OHL toppled government ministers they regarded as weak.

Military operations

In contrast to OHL's questionable interventions in politics and diplomacy, their armies continued to excel. The commanders would agree on what was to be done and then Ludendorff and the OHL staff produced the mass of orders specifying exactly what was to be accomplished. On the western front they stopped packing defenders in the front line, which reduced losses to enemy artillery. They issued a directive on elastic defense, in which attackers who penetrated a lightly held front line entered a battle zone in which they were punished by artillery and counterattacks. It remained German Army doctrine through World War II. Schools taught the new tactics to all ranks. It effectiveness is illustrated by comparing the first half of 1916 in which 77 German soldiers died or went missing for every 100 British to the second half when 55 Germans were lost for every 100 British.[36]

In February 1917, sure that the new French commander General Robert Nivelle would attack and correctly foreseeing that he would try to pinch off the German salient between Arras and Noyon, they withdrew to the segment of the Hindenburg line across the base of the salient, leaving the ground they gave up as a depopulated waste land, in Operation Alberich. The Nivelle Offensive in April 1917 was blunted by mobile defense in depth. Many French units mutinied, though OHL never grasped the extent of the disarray. The British supported their allies with a successful attack near Arras. Their major triumph was capturing Vimy Ridge, using innovative tactics in which infantry platoons were subdivided into specialist groups. The Ridge gave the British artillery observers superb views of the German line but elastic defense prevented further major gains. The British had another success in June 1917 when a meticulously planned attack, beginning with the detonation of mines containing more high explosive than ever fired before, took the Messines Ridge in Flanders. This was a preface to the British drive, beginning at the end of July 1917, toward the Passchendaele Ridge, intended as a first step in retaking the Belgian coast line. At first the defense was directed by General von Lossberg, a pioneer in defense in depth, but when the British adjusted their tactics Ludendorff took over day by day control. The British finally took the Ridge, it was impossible to stop determined attacks that inched forward for preset, limited gains, but the British paid a heavy price.

Ludendorff worried about declining morale, so in July 1917 OHL established a propaganda unit. In October 1917 they began mandatory patriotic lectures to the troops, who were assured that if the war was lost they would “… become slaves of international capital. “.[37] The lecturers were to “ensure that a fight is kept up against all agitators, croakers and weaklings …” [38]

Following the overthrow of the Tsar, the new Russian government launched the Kerensky Offensive in July 1917 attacking the Austro-Hungarian lines in Galicia. After minor successes the Russians were driven back and many of their soldiers refused to fight. The counterattack was halted only after the line was pushed 240 kilometres (150 mi) eastwards. The Germans capped the year in the East by capturing the strong Russian fortress of Riga in September 1917, starting with a brief, overwhelming artillery barrage using many gas shells then followed by infiltrating infantry. The Bolsheviks seized power and soon were at the peace table.

To bolster the wobbly Austro-Hungarian government, the Germans provided some troops and led a joint attack in Italy in October. They sliced through the Italian lines in the mountains at Caporetto. Two hundred and fifty thousand Italians were captured and the rest of Italian Army was forced to retreat to the Grappa-Piave defensive line.

On 20 November 1917 the British achieved a total surprise by attacking at Cambrai. A short, intense bombardment preceded an attack by tanks which led the infantry through the German wire. It was Ludendorff’s 52nd birthday, but he was too upset to attend the celebratory dinner. The British were not organized to exploit their break-through, and German reserves counterattacked, in some places driving the British back beyond their starting lines. The local German commander had not implemented defense in depth.

At the beginning of 1918 almost a million munition workers struck; one demand was peace without annexations. OHL ordered that ” ’all strikers fit to bear arms.’ be sent to the front, thereby degrading military service.” [39]

With Russia out of the war, the Germans outnumbered the Allies on the Western Front. After extensive consultations, OHL planned a series of attacks to drive the British out of the war. During the winter all ranks were schooled in the innovative tactics proven at Caporetto and Riga. The first attack, Operation Michael, was on 21 March 1918 near Cambrai. After a brief hurricane bombardment, coordinated by Colonel Bruchmüller, they slashed through the British lines, surmounting the obstacles that had thwarted their enemies for three years. On the first day they occupied as large an area as the Allies had won on the Somme after 140 days. The Allies were aghast, but it was not the triumph OHL had hoped for: they had planned another Tannenberg by surrounding tens of thousands of British troops in the Cambrai salient,[40] but had been thwarted by stout defense and fighting withdrawal. They lost as many men as the defenders; —the first day was the bloodiest of the war.[41] Among the dead was Ludendorff’s oldest stepson, a younger had been killed earlier. They were unable to cut any vital railway. When Ludendorff motored near the front he was displeased by seeing how: "The numerous slightly wounded made things difficult by the stupid and displeasing way in which they hurried to the rear." [42] The Americans doubled the number of troops being sent to France.

Their next attack was in Flanders. Again they broke through, advancing 30 km (19 mi), and forcing the British to give back all of the ground that they had won the preceding year after weeks of battle. But the Germans were stopped short of the rail junction that was their goal. Next, to draw French reserves south, they struck along the Chemin de Dames. In their most successful attack yet they advanced 12 km (7.5 mi) on the first day, crossing the Marne and stopping only 56 kilometres (35 mi) from Paris. But each triumph weakened their army and its morale. From 20 March 1918 to 25 June the German front lengthened from 390 kilometres (240 mi) to 510 kilometres (320 mi). Then they struck near Reims, to seize additional railway lines for use in the salient, but were foiled by brilliant French elastic tactics. Undeterred, on 18 July 1918 Ludendorff, still “aggressive and confident”,[43] traveled to Flanders to confer about the next attack there. A telephone call reported that the French and Americans led by a mass of tanks had smashed through the right flank of their salient pointing toward Paris, on the opening day of the Battle of Soissons. Everyone present realized that surely they had lost the war. Ludendorff was shattered.

OHL began to withdraw step by step to new defensive lines, first evacuating all of their wounded and supplies. Ludendorff’s communiques, which hitherto had been largely factual, now distorted the news, for instance claiming that American troops had to be herded onto troop ships by special police.[44]

On 8 August 1918 they were completely surprised at Amiens when British tanks broke through the defenses and intact German formations surrendered. To Ludendorff it was the “black day in the history of the German Army”.[45] The German retreats continued, pressed by Allied attacks. OHL still vigorously opposed offering to give up the territory they desired in France and Belgium, so the German government was unable to make a plausible peace proposal.

Ludendorff became increasingly cantankerous, slating his staff without cause, publicly accusing the field marshal of talking nonsense, and sometimes bursting into tears. Bauer wanted him replaced, but instead Oberstabarzt Hochheimer was brought to OHL, he had worked closely with Ludendorff in Poland during the winter of 1915-1916 on plans to bring in German colonists,[35] before the war he had a practice in nervous diseases. The doctor "Spoke as a friend and he listened as a friend.”,[46] convincing Ludendorff that he could not work effectively with one hour of sleep a night and that he must relearn how to relax. After a month away from headquarters his patient had recovered from the severest symptoms of battle fatigue.

Defeat

On 29 September 1918 Ludendorff and Hindenburg told an incredulous Kaiser that they must have an immediate armistice. A new Chancellor, Prince Maximilian of Baden, approached President Woodrow Wilson but his terms were stiff and the Army fought on. The chancellor told the Kaiser that he and his cabinet would resign unless Ludendorff was removed, but that Hindenburg must remain to hold the Army together.[47] The Kaiser called his commanders in, curtly accepting Ludendorff’s resignation and then rejecting Hindenburg’s. Ludendorff would not accompany the field marshal back to headquarters,” I refused to ride with you because you have treated me so shabbily”.[48]

Ludendorff had assiduously sought all of the credit, now he was rewarded with all of the blame. Widely despised, and with revolution breaking out, he was hidden by his brother and a network of friends until he slipped out of Germany in a ludicrous disguise —blue spectacles and a false beard [49] — settling in a Swedish admirer’s country home, until the Swedish government asked him to leave in February 1919. In seven months he wrote two volumes of detailed memoirs. Friends, led by Breucker, provided him with documents and negotiated with publishers. The memoirs testify to his capacity for work, his intellectual brilliance, and the sweeping range of his involvement: ”We regarded ourselves as the leaders of the whole nation in arms … .” [50] Groener (who is not mentioned in the book) characterized it as a showcase of his “'caesar-mania”.[51] He was a brilliant general, according to Wheeler-Bennett he was "... certainly one of the greatest routine military organizers that the world has ever seen",[52] but he was a ruinous political meddler. The influential military analyst Max Delbrüch concluded that “The Empire was built by Moltke and Bismarck, destroyed by Tirpitz and Ludendorff. “ [53]

Reflections on the war, a look to the future

In exile, Ludendorff wrote numerous books and articles about the German military's conduct of the war while forming the foundation for the Dolchstoßlegende, the "stab-in-the-back theory," for which he is considered largely responsible.[54] Ludendorff was convinced that Germany had fought a defensive war and, in his opinion, that Kaiser Wilhelm II had failed to organize a proper counter-propaganda campaign or provide efficient leadership.[54]

Ludendorff was extremely suspicious of the Social Democrats and leftists, whom he blamed for the humiliation of Germany through the Versailles Treaty. Ludendorff claimed that he paid close attention to the business element (especially the Jews), and saw them turn their backs on the war effort by letting profit, rather than patriotism, dictate production and financing.

Again focusing on the left, Ludendorff was appalled by the strikes that took place towards the end of the war and the way that the home front collapsed before the military front did, with the former poisoning the morale of soldiers on temporary leave. Most importantly, Ludendorff felt that the German people as a whole had underestimated what was at stake in the war; he was convinced that the Entente had started the war and was determined to dismantle Germany completely.

Ludendorff wrote:

By the Revolution the Germans have made themselves pariahs among the nations, incapable of winning allies, helots in the service of foreigners and foreign capital, and deprived of all self-respect. In twenty years' time, the German people will curse the parties who now boast of having made the Revolution.

- Erich Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914–1918

Political career

Ludendorff returned to Berlin in February 1919.[55] Staying at the Adlon Hotel, he talked with another resident, Sir Neil Malcome, the head of the British Military Mission. After Ludendorff presented his excuses for the German defeat Malcome said “You mean that you were stabbed in the back?”,[56] ironically coining a key catchphrase for the German right-wing.

On 12 March 1920 5,000 Freikorps troops under the command of Walther von Lüttwitz marched on the Chancellery, forcing the government led by Friedrich Ebert and Gustav Bauer to flee the city. The putschists proclaimed a new government with a right-wing politician, Wolfgang Kapp as new "chancellor". Ludendorff and Max Bauer were part of the putsch. The Kapp Putsch was soon defeated by a general strike that brought Berlin to a standstill. The leaders fled, Ludendorff to Bavaria, where a right-wing coup had succeeded. He published two volumes of annotated —and in a few instances pruned — documents and commentaries documenting his war service.[57] He reconciled with Hindenburg, who began to visit every year.

In May 1923 Ludendorff had an agreeable first meeting with Adolf Hitler, and soon he had regular contacts with National Socialists. On 8 November 1923, the Bavarian Staatskomissar Gustav von Kahr was addressing a jammed meeting in a large beer hall, the Bürgerbräukeller. Hitler, waving a pistol, jumped onto the stage, announcing that the national revolution was underway. The hall was occupied by armed men who covered the audience with a machine gun, the first move in the Beer Hall Putsch. Hitler announced that he would lead the Reich Government and Ludendorff would command the army. The latter was driven over by his surviving stepson Heinz and their servant. He addressed the now enthusiastically supportive audience and then spent the night in the War Ministry, unsuccessfully trying to obtain the army’s backing. The next morning 3,000 armed Nazis formed outside of the Bürgerbräukeller and marched into central Munich, the leaders just behind the flag bearers. They were blocked by a cordon of police, firing broke out for less than a minute. Most of the Nazi leaders were hit or dropped to the ground. Ludendorff and his adjutant Major Streck marched to the police line where they pushed aside the rifle barrels. He was respectfully arrested. He was indignant when sent home while the other leaders remained in custody. Four police officers and 16 Nazis had been killed, including Ludendorff’s servant.

They were tried in early 1924. Ludendorff was acquitted, but Heinz was convicted of chauffeuring him, given a one-year suspended sentence and fined 1,000 marks. Hitler went to prison but was released after nine months. Ludendorff’s 60th birthday was celebrated by massed bands and a large torchlight parade. In 1924, he was elected to the Reichstag as a representative of the NSFB (a coalition of the German Völkisch Freedom Party and members of the Nazi Party), serving until 1928. Gradually he began to part company with Hitler, but nonetheless was persuaded to run for president in March 1925. He received 1.1 per cent of the vote. No one had a majority, so a second round was needed; Hindenburg entered and was narrowly elected. Ludendorff was so humiliated that he broke off their friendship. In 1927 he refused to stand beside the field marshal at the dedication of the Tannenberg memorial. He attacked Hindenburg abusively for not having acted in a "nationalistic soldier-like fashion". The Berlin-based liberal newspaper Vossische Zeitung states in its article "Ludendorff's hate tirades against Hindenburg - Poisonous gas from Hitler's camp" that Ludendorff as of March 29, 1930, was deeply rooted in Hitler’s Nazi ideology.[58]

Tipton notes that Ludendorff was a Social Darwinist who believed that war was the "foundation of human society," and that military dictatorship was the normal form of government in a society in which every resource must be mobilized.[59] The historian Margaret Lavinia Anderson notes that after the war, Ludendorff wanted Germany to go to war against all of Europe, and that he became a pagan worshiper of the Nordic god Wotan (Odin); he detested not only Judaism, but also Christianity, which he regarded as a weakening force.[60] Some even believed that he had become a pacifist.[61]

Last years and death

Ludendorff divorced and married his second wife Mathilde von Kemnitz (1877–1966) in 1926. They published books and essays to prove that the world’s problems were the result of Christianity, especially the Jesuits and Catholics, but also conspiracies by Jews and the Freemasons. They founded the Bund für Gotteserkenntnis (German) (Society for the Knowledge of God), a small and rather obscure esoterical society of Theists that survives to this day.[62] He launched several abusive attacks on his former superior Hindenburg for not having acted in a "nationalistic soldier-like fashion". The Berlin-based liberal newspaper Vossische Zeitung mentions in its article "Ludendorff's hate tirades against Hindenburg - Poisonous gas from Hitler's camp" that Ludendorff as of March 29, 1930, was deeply rooted in Hitler’s Nazi ideology.[58]

By the time Hitler came to power, Ludendorff was no longer sympathetic to him. The Nazis distanced themselves from Ludendorff because of his eccentric conspiracy theories.[63] In January 1933, on the occasion of Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor by President Hindenburg, Ludendorff allegedly sent the following telegram: "I solemnly prophesy that this accursed man will cast our Reich into the abyss and bring our nation to inconceivable misery. Future generations will damn you in your grave for what you have done."[64] Other historians consider this text to be a forgery.[65] In an attempt to regain Ludendorff’s favor, Hitler arrived unannounced at Ludendorff’s home on his 70th birthday in 1935 to promote him to field marshal. Infuriated, Ludendorff allegedly rebuffed Hitler by telling him: "An officer is named General Field-Marshal on the battlefield! Not at a birthday tea-party in the midst of peace.[66] He wrote two further books on military themes, demonstrating that he still could think coherently about war despite his warped prejudices.[67]

Erich Ludendorff died of liver cancer in the private clinic Josephinum in Munich, on 20 December 1937 at the age of 72.[68] He was given — against his explicit wishes — a state funeral organized and attended by Hitler, who declined to speak at his eulogy. He was buried in the Neuer Friedhof in Tutzing.

Decorations and awards

- Knight of the Military Order of Max Joseph (Bavaria)

- Grand Commander with Star of the House Order of Hohenzollern

- Pour le Mérite (Prussia)

- Grand Cross of the Iron Cross

- Knight of the Military Order of St. Henry (Saxony)

- Knight of the Military Merit Order (Württemberg)

- Knight Grand Cross of the House and Merit Order of Peter Frederick Louis with Swords and laurel

- Military Merit Cross, 2nd class (Mecklenburg-Schwerin)

- Military Merit Cross, 1st class with war decoration (Austria-Hungary)

- Gold Military Merit Medal ("Signum Laudis", Austria-Hungary)

Schriften

Books (selection)

- Meine Kriegserinnerungen 1914–1918. Mittler & Sohn, Berlin 1919, 1936.

- Mein militärischer Werdegang. Blätter der Erinnerung an unser stolzes Heer. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1933.

- mit Mitarbeitern: Mathilde Ludendorff – ihr Werk und Wirken. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1937.

- Auf dem Weg zur Feldherrnhalle. Lebenserinnerungen an die Zeit des 9. November 1923. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1937.

- mit Mathilde Ludendorff: Die Judenmacht, ihr Wesen und Ende. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1939.

Smaller publications

- Wie der Weltkrieg 1914 „gemacht“ wurde. Völkischer Verlag, München 1934.

- Die Revolution von oben. Das Kriegsende und die Vorgänge beim Waffenstillstand. Zwei Vorträge. Karl Rohm, Lorch 1926.

- Das Marne-Drama. Der Fall Moltke-Hentsch. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1934.

- „Tannenberg“. Zum 20. Jahrestag der Schlacht. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1934.

- Die politischen Hintergründe des 9. November 1923. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1934.

- Über Unbotmäßigkeit im Kriege. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1935.

- Französische Fälschung meiner Denkschrift von 1912 über den drohenden Krieg. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1935.

- Tannenberg. Geschichtliche Wahrheit über die Schlacht. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1939.

- Feldherrnworte. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1938–1940.

- als Hrsg.: Ludendorffs Volkswarte, Wochenzeitung, erschienen 1929 bis zum Verbot 1933 in München

Publications about Ludendorff

- Margarethe Ludendorff: Als ich Ludendorff's Frau war. Drei Masken Verlag, München 1929.

- Kurt Fügner: General Ludendorff im Feuer vor Lüttich und an der Feldherrnhalle in München 1935.

- Mathilde Ludendorff und Mitarbeiter: Erich Ludendorff – Sein Wesen und Schaffen. Ludendorffs Verlag, München 1938.

- Ludendorff, Erich s. Geburtstag, Zum 75., des Feldherrn Erich Ludendorff am 9. Ostermonds. 1940.

German studies

- Amm, Bettina: Ludendorff-Bewegung. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Judenfeindlichkeit in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Band 5: Organisationen, Institutionen, Bewegungen. De Gruyter, Berlin 2012, S. 393 ff. ISBN 978-3-598-24078-2.

- Gruchmann, Lothar: Ludendorffs „prophetischer“ Brief an Hindenburg vom Januar/Februar 1933. Eine Legende. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Band 47, 1999, S. 559–562.

- Nebelin, Manfred: Ludendorff. Diktator im Ersten Weltkrieg. Siedler, München 2011, ISBN 978-3-88680-965-3.

- Pöhlmann, Markus: Der moderne Alexander im Maschinenkrieg. In: Stig Förster (Hrsg.): Kriegsherren der Weltgeschichte. 22 historische Porträts. Beck, München 2006, ISBN 3-406-54983-7 S. 268–286.

- Puschner, Uwe; Vollnhals, Clemens (Hrgb.); Die völkisch-religiöse Bewegung im Nationalsozialismus; Göttingen 2012 ISBN 978-3-525-36996-8.

- Schwab, Andreas: Vom totalen Krieg zur deutschen Gotterkenntnis. Die Weltanschauung Erich Ludendorffs. In: Schriftenreihe der Eidgenössischen Militärbibliothek und des Historischen Dienstes. Nr. 17, Bern 2005.

- Bruno Thoß (1987), "Ludendorff, Erich", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 15, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 285–290; (full text online)

- Wegehaupt, Phillip: Ludendorff, Erich.. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Bd. 2: Personen. De Gruyter Saur, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-598-44159-2, S. 494 ff. (abgerufen über Verlag Walter de Gruyter Online).

Notes

- 1 2 Saturday, 22 August 2009 Michael Duffy (2009-08-22). "Who's Who – Paul von Hindenburg". First World War.com. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- ↑ Saturday, 22 August 2009 Michael Duffy (2009-08-22). "Who's Who – Erich Ludendorff". First World War.com. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- ↑ Andreas Dorpalen. "Paul von Hindenburg (German president) : Introduction – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- ↑ "Erich Ludendorff (German general) : Introduction – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. 1937-12-20. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- 1 2 Parkinson, Roger (1978). Tormented warrior. Ludendorff and the supreme command. London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-340-21482-1.

- 1 2 "Biografie Erich Ludendorff (German)". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Parkinson, 1978, p. 221.

- ↑ von Stein, General (1920). A War Minister and his work. Reminiscences of 1914-1918. London: Skeffington & Son. p. 39.

- ↑ Lee, John (2005). The warlords : Hindenburg and Ludendorff. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 44.

- ↑ Ludendorff, Erich (1919). Ludendorff’s Own Story. I. New York: Harper and Brothers. p. 31.

- ↑ Ludendorff, M (1929). My married life with Ludendorff. London: Hutchinson. p. 25.

- ↑ Lee, 2005, p. 45

- ↑ Parkinson, 1978. p. 49

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2015). To Hell and back. Europe 1914-1949. London: Allen Lane. p. 77.

- ↑ Ludendorff, Erich (1919). Lundendorff's own story. I. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 220–243.

- ↑ Nazi Empire German Colonialism and Imperialism from Bismarck to Hitler, page 102, Shelley Baranowski, Cambridge University , Press 2010

- ↑ Ludendorff, 1919, I, p. 250.

- ↑ Parkinson, Roger (1978). Tormented warrior, Ludendorff and the supreme Command. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 110.

- ↑ von Müller, Georg (1961). Görlitz, Walter, ed. The Kaiser and his court : the diaries, notebooks, and letters of Admiral Georg Alexander von Müller, chief of the naval cabinet, 1914-1918. London: Macdonald. p. 406.

- ↑ Churchill, Winston S. (1949). The World Crisis. New York: Charles Scribner Sons. p. 685.

- ↑ Binding, Rudolph (1929). A Fatalist at War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 179.

- ↑ Ludendorff, 1919, 2, p. 151.

- ↑ Feldman, Gerald D. (1966). Army, Industry and Labor in Germany 1914-1918. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 180.

- ↑ Lee, John (2005). The warlords : Hindenburg and Ludendorff. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 10.

- ↑ Kitchen, Martin (1976). The Silent Dictatorship. The Politics of the German High Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff,1916-1918. London: Croom Helm. p. 146.

- ↑ Feldman, 1966, p. 478.

- ↑ Ludendorff, 1919,I, p. 10.

- ↑ Ludendorff, 1919, II, 150.

- ↑ Tipton, Frank B. A History of Modern Germany University of California Press, 2003, p. 313

- ↑ Van der Kloot, Wlliam (2014). Great scientists wage the Great War. Stroud: Fonthill. pp. 71–73.

- ↑ Moyer, L. V. (1995). Victory Must be Ours. New York: Hippocrene Books. p. 284.

- ↑ Mendelsohn,, Kurt (1973). The World of Walther Nernst. The rise and Fall of German Science, 1864-1941. London: MacMillan. p. 92.

- ↑ de Gaulle, Charles (2002). The enemy's house divided. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 113.

- ↑ Delbrück, Hans (1922). Ludendorffs selbstportrait. Berlin: Verlag für Politik und Wirtschaft. p. 11.

- 1 2 Ludendorff, 1919, II, p. 76.

- ↑ Van der Kloot, William (2010). World War I fact book. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley. p. 110.

- ↑ Ludendorff, 1919, II, p. 72.

- ↑ Binding, 1929, p. 183.

- ↑ Ludwig, Emil (1935). Hindenburg and the saga of the German revolution. London: William Heinemann. p. 153.

- ↑ Zabecki, David T. (2006). The German 1918 Offensives : A case study in the operational level of war. London: Routledge. p. 114.

- ↑ Herwig, Holger L. (1997). The First World War, Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918. London: Arnold. p. 403.

- ↑ Ludendorff, 1919, II, p. 235.

- ↑ von Lossberg, Fritz (1939). Meine Tätigkeit im Weltkriege 1914-1918. Berlin: E. S. Mittler & Sohn. p. 343.

- ↑ Maurice, Major-General Sir F. (1919). The last four months : The end of the war in the west. London: Cassell. p. 67.

- ↑ Ludendorff, 1919, II, p. 326.

- ↑ Foerester, Wolfgang (1952). Der Feldherr Ludendorff im Unglück. Weisbaden: Limes. p. 75.

- ↑ Watson, Alexander (2014). Ring of Steel. Germany and Austria-Hungary at war 1914-1918. London: Allen Lane. p. 551.

- ↑ von Müller, 1961, p. 413.

- ↑ Goodspeed, D. J. (1966). Ludendorff Soldier: Dictator: Revolutionary. London: Rupert Hart-Davis.

- ↑ Ludendorff, 1919, II, p. 147.

- ↑ Breucker, Wilhelm (1953). Die Tragik Ludendorffs. Eine kritische erinnerung an den general und seine zeit. Berlin: Helmut Rauschenbusch. p. 53.

- ↑ Wheeler-Bennett, John (1938). "Ludendorff: The Soldier and the Politician". Virginia Quarterly. 14 (2): 187.

- ↑ Delbrück, 1922, p. 64.

- 1 2 Nebelin, Manfred: Ludendorff: Diktator im Ersten Weltkrieg, Munich: Siedler Verlag--Verlagsgruppe Random House, 2011

- ↑ John W. Wheeler-Bennett (Spring 1938). "Ludendorff: The Soldier and the Politician". The Virginia Quarterly Review. 14 (2): 187–202.

- ↑ Parkinson, 1978, p. 197.

- ↑ Ludendorff, Erich (1920). Urkunden der Obersten Heeresleitung über ihre Tätigkeit, 1916-18 / herausgegeben von Erich Ludendorff. Berlin: E. S. Mittler.

- 1 2 "Ludendorff beschimpft Hindenburg". Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Frank B. Tipton (2003). A History of Modern Germany. p. 291.

- ↑ Margaret Lavinia Anderson (5 December 2007). Dying by the Sword. The Fall of the Hohenzollern and Habsburg Empires" from History 167b, "The Rise and Fall of the Second Reich.

- ↑ http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/29611696

- ↑ "The God-cognition by Mathilde Ludendorff (1877–1966)". Bund für Gotterkenntnis Ludendorff e.V. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ David Nicholls, Adolf Hitler: A Biographical Companion, ABC-CLIO, 1 Jan 2000, p.159.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian. Hitler. Longman, 1991, p. 426.

- ↑ Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. 47. Jahrgang, Oktober 1999 (PDF; 7 MB), S. 559–562.

- ↑ Parkinson, 1978,p. 224.

- ↑ Ludendorff, Erich (1936). The nation at war. Translated by A.S. Rappoport. London: Hutchinson.

- ↑ Ludendorffs Verlag: Der letzte Weg des Feldherrn Erich Ludendorff, München 1938, S. 8: Das Kranken- und Sterbezimmer im Josephinum in München.

References

- Asprey, Robert B (1991). The German High Command at War: Hindenburg and Ludendorff and the First World War. New York: W. Morrow. ISBN 0-688-08226-2.

- Goodspeed, Donald J. (1966). Ludendorff: Genius of World War I. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Ludendorff, Erich (1971) [1920]. Ludendorff's Own Story: August 1914 – November 1918; the Great War from the siege of Liège to the signing of the armistice as viewed from the grand headquarters of the German Army. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 0-8369-5956-6.

- Lee, John (March 2005). The Warlords: Hindenburg and Ludendorff (Hardback). London: Orion Books. ISBN 0-297-84675-2.

- Livesay, John Frederick Bligh (1919). Canada's Hundred Days: With the Canadian Corps from Amiens to Mons, Aug. 8 — Nov. 11, 1918. Toronto: Thomas Allen.

- Ludendorff, Erich. The Coming War. Faber and Faber, 1931. (= "Weltkrieg droht auf deutschem Boden")

- [1]

- Parkinson, Roger (1978). Tormented Warrior. Ludendorff and the supreme command. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-21482-1.

- Serle, Geoffrey (1982). John Monash: A Biography. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84239-9.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Erich Ludendorff. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Erich Ludendorff. |

- Ludendorff by H. L. Mencken published in the June 1917 edition of the Atlantic Monthly

- Biography of Erich Ludendorff From Spartacus Educational

- My War Memories by Erich Ludendorff at archive.org

- Erich Ludendorff's grave at Find-A-Grave

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Woodrow Wilson |

Cover of Time Magazine 19 November 1923 |

Succeeded by Hugh S. Gibson |

- ↑ Ludendorff, Erich. The Nation at War. Hutchinson, London, 1936. (= "Der totale Krieg")