Battle of Tannenberg

| Battle of Tannenberg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War I | |||||||

Russian prisoners of war after the Battle of Tannenberg. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Eighth Army (150,000)[1] | Second Army (230,000)[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

10,000–15,000 killed or wounded[3] 12,000 killed or wounded[4] official German data 21-30/08/14: 1,726 KIA; 7,461 WIA; 4,686 MIA; Total: 13,873[5] |

78,000 killed or wounded; 92,000 POW; 350 guns captured[6][7] Total: 170,000 | ||||||

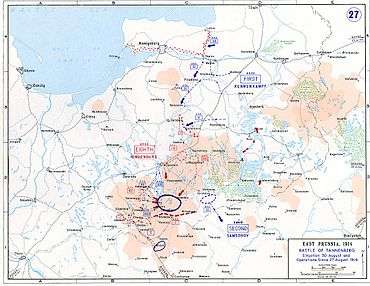

The Battle of Tannenberg was fought between Russia and Germany from 26–30 August 1914, during the first month of World War I. The battle resulted in the almost complete destruction of the Russian Second Army and the suicide of its commanding general, Alexander Samsonov. A series of follow-up battles (First Masurian Lakes) destroyed most of the First Army as well and kept the Russians off balance until the spring of 1915. The battle is particularly notable for fast rail movements by the Germans, enabling them to concentrate against each of the two Russian armies in turn, and also for the failure of the Russians to encode their radio messages. It brought high prestige to Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and his rising staff-officer Erich Ludendorff.

Although the battle actually took place near Allenstein (now Olsztyn, Poland), Hindenburg named it after Tannenberg (now Stębark, Poland), 30 km to the west, to avenge the defeat of the Teutonic Knights at the earlier Battle of Grunwald of 1410 having also the same name.

Background

The French war plan was to attack as soon as their army was mobilized to drive the Germans from Alsace and Lorraine. If the British joined as promised, they would become the left flank. Their Russian allies would have a massive army, more than 95 divisions, but their mobilization would inevitably be somewhat slower. Getting their men to the front would also be delayed because their railway network was far behind Western European standards; for instance, three-quarters was still single-tracked.[8] They intended to have 27 divisions at the front by day 15 and 52 by day 23, but it would take 60 days before 90 divisions were in action.[9] Despite their difficulties, the Russians promised the French that they would promptly engage the armies of Austria-Hungary in the south and on day 15 would invade German East Prussia.[10]

East Prussia was a vulnerable salient thrust into Russian territory, extending from the Vistula River in the west to the border with Lithuania in the east, a distance of roughly 190 km (120 mi). On the north was the Baltic and on the south was the border with Poland; it was about 130 km (81 mi) wide. Somewhat east of the center of the province was the heavily fortified peninsula on which its capital Königsberg (Kaliningrad, Russia) was located.

The Russians would rely on two of their three railways that ran up to the border; each would provision an army. The railways ended at the border, as Russian trains operated on a different rail gauge than Western Europe. Consequently, its armies could be transported by rail only as far as the German border and could use Prussian railways only with captured locomotives and rolling stock. The First Army would use the line that ran from Vilnus, Lithuania, to the border 136 km (85 mi) southeast of Königsberg. The Second Army railway ran from Warsaw, Poland, to the border 165 km (103 mi) southwest of Königsberg. The two armies would take the Germans in a pincers. The Russian supply chains would be ungainly because—for defense—on their side of the border there were only a few sandy tracks rather than proper macadamized roads. Adding to their supply problems, the Russians deployed large numbers of cavalry and Cossacks; every day each horse needed ten times the resources that a man required.[11]

The First Army commander was Gen. Pavel Karlovitch Rennenkampf, who in the Russo-Japanese War had earned a reputation for "exceptional energy, determination, courage, and military capability." [12] The Second Army, coming north from Warsaw, was under Gen. Alekesander Vasilevich Samsonov, who was “ . . . possessed of a brilliant mind, reinforced by an excellent military education”. Since commanding a division in the war with Japan he had been governor of Turkestan. The two armies were directed by the military governor of Warsaw, who in wartime commanded the Northwest Military District, Gen. Yakov Grigorevich Zhilinskiy. His duties in Manchuria had been more diplomatic than military. Before moving to Warsaw he had been Chief of the Russian General Staff for two years. He set up his headquarters in Volkovysk. (Vawkavysk, Belarus), about 410 km (250 mi) from Königsberg.

Communications would be a daunting challenge. The Russian supply of cable was insufficient to run telephone or telegraph connections from the rear; all they had was needed for field communications. Therefore, they relied on mobile wireless stations, which would link Zhilinskiy to his two army commanders and with all corps commanders. The Russians were aware that the Germans had broken their ciphers, but they continued to use them until war broke out. A new code was ready but they were still very short of the code books. Zhilinskiy and Rennenkampf each had one; Samsonov did not.[13] Hence, many messages were sent in the clear, hoping that they would not be intercepted. The Germans also used wireless during their invasions of Belgium and France.

The German Schlieffen Plan proposed to defeat France swiftly while the Russians were mobilizing. Then Germany's armies would shift by train to the Eastern Front. Therefore, East Prussia was garrisoned by a single army, the Eighth, commanded by Gen. Maximilian von Prittwitz und Gaffron, which was to hold back the Russians while the outcome in the West was decided. A tangle of lakes, marshes and dense woods characterized the province, which would help defenders. When the war began the bulk of the German Eighth Army was southwest of Königsberg, ready to defend either the Western or the Southern frontier: 485,000 Russians were facing 173,000 Germans. More than half of the men in both armies just had been mobilized, so many were not yet fighting fit.

Prelude: 17–22 August

Rennenkampf’s First Army crossed the frontier on 17 August 1914, moving westward slowly. This was sooner than the Germans anticipated, because the Russian mobilization, including the Baltic and Warsaw districts, had begun secretly on 25 July, not with the Tsar’s proclamation on 30 July.[14] They were attacked at Stallupönen by a division of the German I Corps under Lt. Gen. Hermann von François. The Russians were driven back and lost 3,000 men as prisoners, but I Corps was ordered by Prittwitz, who had not authorized the attack, to pull back to Gumbinnen to concentrate his forces. The Russian advance continued on the afternoon of 18 August and on the following day.

Prittwitz attacked near Gumbinnen on 20 August, when he knew from intercepted wireless messages that Rennenkampf’s infantry was resting. German I Corps was on their left, XVII Corps commanded by Lt. Gen. August von Mackensen in the center and I Reserve Corps led by Gen. Otto von Below on the right. A night march enabled one of François’ divisions to hit the Russian XX Corps' right flank at 04:00. Rennenkampf’s men rallied to stoutly resist the attack. Their artillery was devastating until they ran out of ammunition, then the Russians retired. I Corps attacks were halted at 16:00 to rest men sapped by the torrid summer heat. François was sure they could win the next day. On his left Mackensen’s XVII Corps launched a vigorous frontal attack but the Russian infantry held firm. That afternoon the Russian heavy artillery struck back—the German infantry fled in panic, their artillery limbered up and joined the stampede. Prittwitz ordered I Corps and I Reserve Corps to break off the action and retreat also. At noon he had telephoned Field Marshal von Moltke at OHL (Oberste Heeresleitung, Supreme Headquarters) to report that all was going well; that evening he telephoned again to report disaster. His problems were compounded because an intercepted wireless message disclosed that the Russian II Army included five Corps and a cavalry division, and aerial scouts saw their columns marching across the frontier.[15] They were opposed by a single reinforced German Corps, the XX, commanded by Lt. Gen. Friedrich von Scholtz. Prittwitz excitedly but inconclusively and repeatedly discussed the dreadful news with Moltke that evening on the telephone, shouting back and forth. At 20:23 Eighth Army telegraphed OHL that they would withdraw to West Prussia.[16]

However, by the next morning, 21 August, Eighth Army staff realized that because Samsonov’s II Army was closer to the Vistula crossings they must relocate most of their forces to join with XX Corps to block Samsonov before they could withdraw further. Now Moltke was told that they would only retreat a short way; François protested directly to the Kaiser about his panicking superiors.[17] That evening Prittwitz reported that the German 1st Cavalry Division had disappeared. His next call disclosed that they had ridden in with 500 prisoners. Probably Moltke had already decided to replace both Prittwitz and his highly regarded chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Alfred von Waldersee. On the morning of 22 August their replacements, Col. Gen. Paul von Hindenburg and Maj. Gen. Erich Ludendorff, were notified of their new assignments.

The Eighth Army issued orders to move toward Samsonov’s Second Army. I Corps was closest to the railway, so it would move by train to support the right of XX Corps, while the other two German corps would march the shorter distance to XX Corps' left. The First Cavalry Division with some older garrison troops would remain to screen Rennenkampf. On the afternoon of 22 August the head of the Eighth Army field railways was informed by telegraph that new commanders were coming by special train. The telegram relieving their former commanders came later. I Corps was moving over more than 150 km (93 miles) of rail, day and night, one train every 30 minutes, with 25 minutes to unload instead of the customary hour or two.[18]

After the battle at Gumbinnen Rennenkampf decided to keep his First Army in position to resupply and to be in good positions if the Germans attacked again. Both Russian armies were having serious supply problems; everything had to be carted up from the railheads because they could not use the East Prussian railway track, and many units were hampered by lack of field bakeries, ammunition carts and the like. The Second Army also was hampered by incompetent staff work and poor communications. Poor staff work not only exacerbated supply problems but, more importantly, caused Samsonov during the fighting to lose operational control over all but the two corps in his immediate vicinity (XIII & XV Corps).[19]

Battle

Consolidation of the German Eighth Army

The new commanders arrived at Marienburg at 14:00 on 23 August; they had met for the first time on their special train the previous night and now they rendezvouzed with the Eighth Army staff. Hindenburg knew none of them. Ludendorff knew the senior officer, deputy Chief of Operations Col. Max Hoffmann, because they had served together and had been neighbors in Berlin and he had met several of the junior men. First they sorted out the orders that had been issued for concentrating most of Eighth Army against Samsonov—each corps had received orders from the Eighth Army and also from Ludendorff—which rankled the staff. However, the orders were almost identical because they were dictated by the situation. I Corps was moving by the rail line. The Eighth Army had ordered it further west to shield the Vistula crossings, but now it would detrain at Deutsch-Eylau, where it could support the right of XX Corps. XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps would march towards the left of XX Corps. Ludendorff had delayed their marches for a day to rest while remaining in place should Rennenkampf attack. The German 1st Cavalry Division and some garrison troops of older men would remain as a screen just south of the eastern edge of the Königsberg defenses, facing Rennenkampf's First Army. The eastern portion of the Königsberg defenses was the only part that was fully manned, while the approaches from the south were entirely open.

Then the new commanders raised the stakes dramatically.[20] They must do more than stop Samsonov in his tracks, as they had tried to block and push back Rennenkampf. Samsonov must be annihilated before they turned back to deal with Rennenkampf.[21] For the moment Samsonov would be opposed only by the forces he was already facing, XX Corps, mostly East Prussians who were defending their homes. The bulk of the Second Russian Army was still coming towards the front; if necessary, they would be allowed to push further into the province while the German reinforcements assembled on the flanks, poised to encircle the invaders—just the tactics instilled by Schlieffen.[22] The danger was that if Rennenkampf’s First Army marched southwest they would appear on the Eighth Army's extreme left flank. Thanks to their consolidation, the coming battle would be fought with 1.8 Russians facing each German. OHL was informed that they were moving to envelop the invaders.

Early phases of battle: 23–26 August

Zhilinskiy had agreed to Samsonov’s proposal to start the Second Army’s advance further westward than originally planned, separating them even further from Rennenkampf’s First Army. On 22 August Samsonov's forces encountered Germans all along their front and pushed them back in several places. Zhilinskiy ordered him to pursue vigorously. They already had been advancing for six days in torrid heat without sufficient rest along primitive roads, averaging 24 km (15 mi) a day and had outrun their supplies [23] On 23 August they attacked the German XX Corps, which retreated to the Orlau-Frankenau line that night. The Russians followed, and on the 24th they attacked again; the now partially entrenched XX Corps temporarily stopped their advance before retreating to avoid possible encirclement. At one stage the chief of staff of the corps directed artillery fire onto his own dwelling.[24]

Samsonov saw a wonderful opportunity because, as far as he was aware, both of his flanks were unopposed. He ordered most of his units to the northwest, toward the Vistula, leaving only his VI Corps to continue north towards their original objective of Seeburg. He did not have enough aircraft or skilled cavalry to detect the German buildup on his left. Rennenkampf mistakenly reported that two of the German Corps had sheltered in the Königsberg fortifications.[25]

On 24 August Hindenburg, Ludendorff and Hoffmann motored along the German lines to meet Scholtz and his principal subordinates, sharing the roads with panic-stricken refugees; in the background were columns of smoke from burning villages ignited by artillery shells. They could keep control of their army because most of the local telephone operators remained at their switchboards, carefully tracking the motorcade. Along the way they drove through the village of Tannenberg, which reminded the two younger men of the defeat of the Teutonic Knights there by the Poles and Lithuanians in 1410; Hindenburg had been thinking about that battle since the evening before when he strolled near the ruins of the castle of the Teutonic Order. In 1910 Slavs had commemorated their triumph on the old battlefield.[26] By telephone with headquarters they were reassured that Rennenkampf’s army was moving forward, but slowly—his heavy wagons were sinking into the East Prussian sands. They knew about Samsonov’s proposed movements from a wireless intercept that agreed perfectly with papers found on the body of a Russian officer killed at Gumbinnen. When they met François he was told that Samsonov was moving northwest, to turn what he believed to be the German right flank. I Corps was ordered to attack the Russian left wing at Usdau on the next day, 25 August. François objected vigorously: only part of his corps had arrived and his artillery would not be detrained and ready before 26 August. Ludendorff screeched at him until François finally agreed to attack, but with the proviso that because his ammunition column was still on the road, his men must charge with bayonets. By setting Usdau as the objective, the commanders realized that part of the Russian Second Army would escape the trap.

On the way back to headquarters Hoffmann received new radio intercepts. Rennenkampf's most recent orders from Zhilinskiy were to continue due west, not turn southward towards Samsonov, who was instructed to continue his own drive northwest. Based on this information Scholtz formed a new defensive flank along the Drewenz River, while his main line strengthened their defenses. Back at headquarters Hindenburg told the staff, “Gentlemen. Our preparations are so well in hand that we can sleep soundly tonight." [27]

As the battle was beginning OHL telegraphed the Eighth Army that three army corps and a cavalry division would be sent to East Prussia. Ludendorff replied that they would arrive too late for the present battle, but would be welcome if they could be spared. Moltke was optimistic about their progress in France and Belgium and two army corps and the cavalry were sent.

Main battle: 26–30 August

Samsonov’s cavalry detected the German buildup on their left, so he ordered reinforcements to extend the Russian line, but it would take hours or even days for them to arrive. True to his word, on 26 August François advanced part of his 1st Division toward the Russian outposts at 08:00, where—despite telephone prodding from the Eighth Army—they only skirmished at a distance until noon. By then the railways had brought up the rest of I Corps including their artillery. Finally they drove the Russian outposts back, but at 15:45 François halted in order to organize a strong attack on the following day by men with full stomachs and ammunition pouches. Scholtz followed his orders, which were to make sure that Russians were not slipping past his flanks, which would make it difficult to spring the trap. On his right he attacked to push back the Russian 2nd Division and almost destroyed it. On his left the German 3rd Reserve Division repelled an attack by the Russian VI Corps. It was a different story in the thinly held center, where the Russian XIII Corps advanced toward the road center of Allenstein almost unopposed.

Zhilinskiy was visited by the commander of the Russian Army, the Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia, who ordered him to support Samsonov.[28] Therefore, Rennenkampf ordered two of his corps to invest Königsberg, while the other two were to march to make contact with Samsonov. These orders were sent by wireless in the clear. The next day the Russian First Army's cavalry started riding towards their Second Army, but their infantry waited for resupply.

That evening the Eighth Army’s staff was on edge. Little had been achieved during the day, when they had intended to spring the trap. XX Corps had done well on another torrid day, but now was exhausted. On their far left they knew that XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps were coming into action, but headquarters had learned little about their progress. In fact, XVII Corps had defeated the Russian VI Corps, which fled back along the roads. XVII Corps had endured long marches in sweltering weather, but some men still had the energy to pursue on bicycles requisitioned from civilians.[29] To add to their worries, German aerial scouts reported that still more of Samsonov’s army was detraining at his railhead. Another aviator mistakenly reported that Rennenkampf’s infantry was now heading towards them. The Eighth Army might be the one in the trap.

Hoffmann, who had been an observer with the Japanese in Manchuria, tried to ease their nerves by telling how Samsonov and Rennenkampf had quarreled during that war, so they would do nothing to help one another. It was a good story that Hoffmann treasured and retold frequently,[30] so it reappears in many histories, but not in either Hindenburg’s or Ludendorff’s memoirs.

In Hindenburg’s words “. . . firm resolution began to yield to vacillation . . . ” [31] At dinner Ludendorff was visibly distraught, toying with his bread, and finally abruptly asked to speak alone with Hindenburg. When Ludendorff emerged from their tête-a-tête he issued the orders to continue the attack on Samsonov. The rest of the German forces coming onto their left wing were swinging into place by forced marches. Samsonov’s II Army was now facing Germans along a 100 km (62 mi) line.

François was ready to attack the Russian left decisively on 27 August, hitting I Russian Corps. His artillery barrage was overwhelming, and soon he had taken the key town of Usdau. In the center the Russians continued to strongly attack the German XX Corps and to move northwest from Allenstein. The German XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps pushed the Russian right wing they had bloodied the day before further back. Gen. Basil Guruko, then commanding the Russian First Army Cavalry Division, and from 1916-17 chief of the general staff, was told later that Samsonov did not know what was happening on his flanks because he was observing the action from a rise in the ground a distance from his wireless set and reports were not relayed to him.[32] It was late in the day before he realized that his army was in frightful danger.

On the morning of 28 August the German commanders were motoring along the front when they were shown a report from an aerial observer that Rennenkampf was moving towards their rear. Ludendorff announced that the attack on the Second Army must be broken off. Hindenburg led him behind a nearby hedge, when they emerged Hindenburg calmly said that operations would continue as planned.[33] Before long they learned that the report of Rennenkampf’s movement was mistaken. Samsonov’s I Corps on the left and VI Corps on the right were both retreating. His center had received so little food and ammunition that they were unable to keep attacking. They were ordered to retreat southeast to obtain what they needed to fight. Samsonov asked that Rennenkampf be ordered to help. It was too late. François by this time had advanced due east, moving further than his orders specified, to form a line south of the Russians between Neidenburg and Willenberg, and XVII German Corps had swung southwest to meet him. The noose was in place. The Russians who had been attacking were surrounded.

On 29 August the troops from the Russian Second Army’s center who were retreating south ran into a German defensive line. Those Russians who tried break through by dashing across open fields heavy with crops were mown down. They were in a cauldron centered at Frogenau, east of Tannenberg, and throughout the day were relentlessly pounded by artillery. Many surrendered—long columns of prisoners jammed the roads away from the battleground. Hindenburg and Ludendorff watched from a hilltop, with only a single field telephone line; thereafter they stayed closer to the telephone network. Hindenburg met one captured Russian corps commander that day, another on the day following. On 30 August the Russians remaining outside of the cauldron tried unsuccessfully to break open the snare. Rather than report the loss of his army to Tsar Nicholas II, Samsonov disappeared in the woods that night and committed suicide. His body was found in the following year and returned to Russia by the Red Cross.[34]

On 31 August Hindenburg formally reported to the kaiser that three Russian army corps (XIII, XV and XXIII) had been destroyed. The two corps (I and VI) that had not been caught in the cauldron had been severely bloodied and were retreating back to Poland. He requested that the battle be named Tannenberg (an imaginative touch that both Ludendorff and Hoffmann claimed as their own).[35][36]

Samsonov's Second Army had been almost annihilated: 92,000 captured, 78,000 killed or wounded and only 10,000 (mostly from the retreating flanks) escaping. The Russians had lost 350 big guns. The Germans suffered just 12,000 casualties out of the 150,000 men committed to the battle.[37] Sixty trains were required to take captured Russian equipment to Germany. Other historians give smaller numbers for Russian killed and wounded, which were never properly recorded.[38] For instance, 30,000 Russian killed or wounded, with 13 generals and 500 guns captured.[39]

The Russian First Army had been so slowed by the combative German cavalry screen that by the time the battle was over their closest unit was still perhaps as much as 70 km (43 mi) from the trapped Second Army. Other Russian units were scattered back along the line to Königsberg, leaving the First Army itself in a dangerously spread-out position.

Aftermath

To David Stevenson it was "a major victory but far from decisive",[40] because the Russian First Army was still in East Prussia. It set the stage for the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes a week later, when the reinforced German Eighth Army confronted the Russian First Army. Rennenkampf retreated hastily back over the pre-war border before they could be encircled.

Field Marshal Sir Edmund Ironside saw Tannenberg as the “. . . greatest defeat suffered by any of the combatants during the war”.[41] It was a tactical masterpiece that demonstrated the superior skills of the German army. Their pre-war organization and training had proven themselves, which bolstered German morale while severely shaking Russian confidence. Nonetheless, as long as the great battle in the West continued the outnumbered Germans had to remain on the defensive in the East, anticipating that the Russians would make another thrust from Poland against Germany, and because the Russians had bested the Austro-Hungarians in the Battle of Galicia; their allies would need help.

The Russian official inquiry into the disaster blamed Zhilinskiy for not controlling his two armies. He was replaced in the Northwest Command and sent to liaise with the French. Rennenkampf was exonerated, but was retired after a dubious performance in Poland in 1916.[42]

Hindenburg was hailed as an epic hero, Ludendorff was praised, but Hoffmann was generally ignored by the press. Apparently not pleased by this, he later gave tours of the area, noting, "This is where the Field Marshal slept before the battle, this is where he slept after the battle, and this is where he slept during the battle." However, Hindenburg countered by saying, "If the battle had gone badly, the name 'Hindenburg' would have been reviled from one end of Germany to the other." Hoffmann is not mentioned in Hindenburg’s memoirs. In his memoirs Ludendorff takes credit for the encirclement[43] and most historians give him full responsibility for conducting the battle. Hindenburg wrote and spoke of “we”, and when questioned about the crucial tête-á-tête with Ludendorff after dinner on 26 August resolutely maintained that they had calmly discussed their options and resolved to continue with the encirclement. Military historian Walter Elze wrote that a few months before his death Hindenburg finally acknowledged that Ludendorff had been in a funk that evening.[44] Hindenburg would also remark, “After all, I know something about the business, I was the instructor in tactics at the War Academy for six years”.[45]

Post-war legacy

The battle is at the center of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's novel August 1914.

A German monument was completed in 1927. However, it was blown up by the Germans during the retreat in January 1945.[46]

Ludendorff later revisited the battle site when naming his own political movement, the Tannenbergbund, formed in 1925.

German film director Heinz Paul made a film, Tannenberg, about the battle, shot in East Prussia in 1932.

The video game Darkest of Days features the Battle of Tannenberg as one of the game's signature historical locations a player gets to explore.

Comparable historical battles

Hindenburg and Ludendorff's daring maneuvers to surprise and defeat in detail two enemy armies may be compared to a classic example such as the Battle of Austerlitz. However, the disastrous consequences of failing to defeat each enemy force in turn can be seen at the Battle of Waterloo.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Hastings, Max., 2013; pg. 281.

- ↑ Hastings, Max. Catastrophe: Europe goes to war 1914 London: William Collins, 2013; pg. 281.

- ↑ Spencer Tucker, The Great War: 1914-1918, 2002, p. 43

- ↑ Hastings, Max., 2013; pg. 281.

- ↑ Sanitätsbericht über das deutsche Heer im Weltkriege 1914/1918, III. Band, Berlin 1934, S. 36

- ↑ Sweetman 2004, p. 158

- ↑ Ian F. W. Beckett, The Great War: 1914-1918, 2014, p. 76

- ↑ Strachan, H. (2001) The First World War. Volume I. To Arms. Oxford University Press, p.298.

- ↑ Strachan (2001) p.312.

- ↑ Herwig, H. L. (1997). The First World War, Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918. Arnold, London, p. 53.

- ↑ Van Creveld, M. (1977). Supplying War. Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Gourko, G.B. (1918) Memories & Impressions of war and revolution in Russia, 1914-1917. John Murray, London, p. 10-11.

- ↑ Norman, B. (1973). Secret warfare : the battle of codes and ciphers. David & Charles, Newton Abbot, p. 62.

- ↑ McMeekin, S. (2011) The Russian Origins of the First World War. Harvard University Press, p. 67.

- ↑ Showalter, 1991, pp. 91-94.

- ↑ Showalter, 1991, p. 195

- ↑ Showalter, 1991, p. 196.

- ↑ Lincoln, W. B., (1986) Passage through Armageddon. The Russians in war & revolution 1914-1918. Simon & Schuster, p. 72-73.

- ↑ Golovine, Nicholas N. (1931). The Russian army in the World War. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Hindenburg, P. von, (1921) Out of my life, Harper, vol. 1, p. 109.

- ↑ Showalter, 1991 pp. 106-123

- ↑ Schlieffen, Alfred, Graf von (1925). Cannae. Berlin: E. S. Mittler.

- ↑ Lincoln, 1986, p. 73.

- ↑ Showalter, 1991, p. 238

- ↑ Asprey, R. B.(1991) The German High Command at War; Hindenburg and Ludendorff conduct World War I. London: William Morrow, p. 74.

- ↑ Egremont, M., (2011) Forgotten land : journeys among the ghosts of East Prussia. London: Picador.

- ↑ Showalter, 1991, p. 233.

- ↑ Asbury, 1991, p. 78.

- ↑ Showalter, 1991, p. 263.

- ↑ Hoffmann, General Max (1999) [1924]. The war of lost opportunities. Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. p. 34.

- ↑ Hindenburg, 1921, p. 117

- ↑ Gourko, General Basil , (1918) Memories & Impressions of war and revolution in Russia, 1914-1917. London: John Murray.

- ↑ Showalter 1991, p. 291.

- ↑ Stevenson 2004, p. 68

- ↑ Hindenburg , 1921, vol. 1, p. 114.

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/582679/Battle-of-Tannenberg

- ↑ Hastings, Max, (2013) Catastrophe: Europe goes to war 1914. London: William Collins, 2013; pg. 281.

- ↑ Showalter, 1991, p. 323.

- ↑ Gray, Randall; Argyle, Christopher (1990). Chronicle of the First World War. New York: Oxford. p. vol. I 282.

- ↑ Stevenson 2004, p. 69

- ↑ Ironside, Major General Sir E. (1925). Tannenberg: The First Thirty Days in East Prussia. W. Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh. 195.

- ↑ Bohon, J.W.(1996) “Zhilinsky” in The European Powers in the First World War, ed, Tucker, S.C., Garland, New York, p. 768.

- ↑ Ludendorff, 1919, p. 59.

- ↑ Showalter, 1991, p. 241.

- ↑ Papen, F. von. (1952). Memoirs. London: A. Deutsch, p. 177.

- ↑ A Monument to German Pride: A history of the Tannenberg Memorial

Further reading

- Clark, Christopher (2006), Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Fall of Prussia, 1600—1947, Cambridge, ISBN 978-0-674-02385-7

- Durschmied, Erik (2000), "10", The hinge factor: how chance and stupidity have changed history, Arcade, ISBN 978-1-55970-515-8

- Harrison, Richard W. (1991), "Samsonow and the Battle of Tannenberg, 1914", in Bond, Brian, Fallen Stars. Eleven Studies of Twentieth Century Military Disaster, London: Brassey's, pp. 13–31, ISBN 0-08-040717-X

- Haufler, Hervie (2003), Codebreakers' Victory: How the Allied Cryptographers Won World War II, New York: New American Library, p. 10, ISBN 978-0-451-20979-5

- Jaques, Tony (2007), Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A-E, Greenwood, ISBN 978-0-313-33537-2

- Showalter, Dennis E (1991), Tannenberg: Clash of Empires, 1914 (2004 ed.), Brassey's, ISBN 978-1-57488-781-5

- Stevenson, David (2004), 1914—1918: The History of the First World War, Penguin Books Ltd, ISBN 978-0-14-026817-1

- Stone, David (2015). The Russian Army in the Great War: The Eastern Front, 1914-1917. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700620951.

- Strachan, Hew (2001), The First World War, Oxford: Oxford, ISBN 0-19-926191-1

- Sweetman, John (2004), Tannenberg 1914 (1st ed.), London: Cassell, ISBN 978-0-304-35635-5

- Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim (1994), The Guns of August, New York: Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-345-47609-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Tannenberg (1914). |

_von_Nicola_Perscheid.jpg)