Esalen Institute

Esalen main campus | |

| Founder(s) |

Michael Murphy Dick Price |

|---|---|

| Established | 1962 |

| Focus | Humanistic alternative education |

| President | Gordon Wheeler |

| Owner | Esalen Institute |

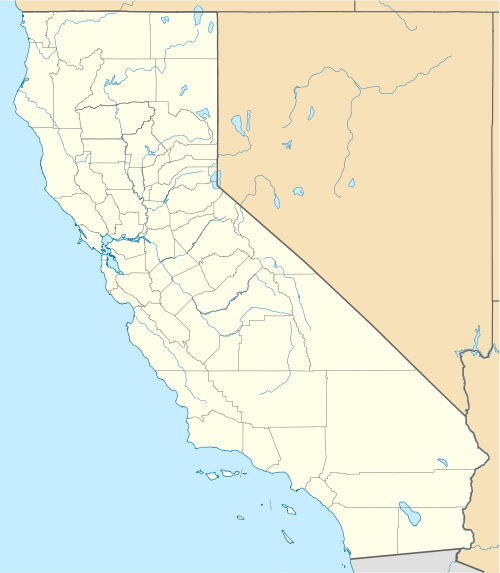

| Location | Slates Hot Springs, Big Sur, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 36°07′37″N 121°38′30″W / 36.12701°N 121.64159°WCoordinates: 36°07′37″N 121°38′30″W / 36.12701°N 121.64159°W |

| Address | 55000 Highway One, Big Sur, CA 93920[1] |

| Website | Esalen Institute |

Esalen Location in California | |

The Esalen Institute, commonly just called Esalen, is a non-profit American retreat center and intentional community in Big Sur, California which focuses on humanistic alternative education.[2] The Institute played a key role in the Human Potential Movement beginning in the 1960s. Its innovative use of encounter groups, a focus on the mind-body connection, and their ongoing experimentation in personal awareness introduced many ideas that later became mainstream.[3]

Esalen was founded by Stanford graduates Michael Murphy and Dick Price in 1962. Their intention was to support alternative methods for exploring human consciousness, what Aldous Huxley described as "human potentialities".[4][5] Over the next few years, Esalen became the center of practices and beliefs that make up the New Age movement, from Eastern religions/philosophy, to alternative medicine and mind-body interventions, to Gestalt Practice.[6]

Price ran the Institute until he was killed in a hiking accident in 1985. In 2012, the board hired professional executives to help raise money and keep the Institute profitable. Esalen offers over 500 workshops yearly[7] in areas including personal growth, meditation, massage, Gestalt Practice, yoga, psychology, ecology, spirituality, and organic food.[8]

Early history

The grounds of the Esalen Institute were first home to a Native American tribe known as the Esselen, from whom the institute adopted its name.[9] Carbon dating tests of artifacts found on Esalen's property have indicated a human presence as early as 2600 BCE.[10]

The location was homesteaded by Thomas Slate on September 9, 1882, when he filed a land patent under the Homestead Act of 1862.[11] The settlement began known as Slates Hot Springs. It was the first tourist-oriented business in Big Sur, frequented by people seeking relief from physical ailments. In 1910, the land was purchased by Henry Murphy,[12] a Salinas, California, physician. The official business name was "Big Sur Hot Springs" although it was more generally referred to as "Slate's Hot Springs".[13]

Founding of Esalen Institute

Stanford grads meet

Michael Murphy and Dick Price both attended Stanford University in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[14] Both had developed an interest in human psychology. Price was influenced by a lecture he heard Aldous Huxley give in 1960 titled "Human Potentialities". After graduating from Stanford, Price attended Harvard University to continue studying psychology. Murphy, meanwhile, traveled to Sri Aurobindo's ashram in India where he resided for several months[15] before returning to San Francisco. They met in San Francisco at the suggestion of Frederic Spiegelberg, a Stanford professor of comparative religion and Indic studies, with whom both had studied.[16]

Lease property

Price and Murphy wanted to create a venue where non-traditional workshops and lecturers could present their ideas free of the dogma associated with traditional education. The two began drawing up plans for a forum that would be open to ways of thinking beyond the constraints of mainstream academia, while avoiding the dogma so often seen in groups organized around a single idea promoted by a charismatic leader. They envisioned offering a wide range of philosophies, religious disciplines and psychological techniques.[17]

In 1961, they went to look at property owned by the Murphy family at Slates Hot Springs in Big Sur.[18] It included a run-down hotel occupied in part by members of a Pentecostal church.[19] The property was patrolled by gun-toting Hunter S. Thompson. Gay men from San Francisco filled the baths on the weekends.[19]

Henry Murphy's widow and Michael's grandmother Vinnie "Bunnie" MacDonald Murphy, who owned the property, lived 62 miles (100 km) away in Salinas. She had previously refused to lease the property to anyone, even turning down an earlier request from Michael. She was afraid her grandson was going to "give the hotel to the Hindus," Murphy later said. Not long after, Thompson attempted to visit the baths with friends and got into a fistfight when some of the gay men jumped him. The men almost tossed him over the cliff. Murphy's father, a lawyer, finally persuaded his mother to allow her grandson to take over[19] and she agreed to lease the property to them in 1962.[20][21][22] The two men used capital that Price obtained from his father, who was a vice-president at Sears.[23] They incorporated their business as a non-profit named Esalen Institute in 1963.[24][25]

Develop counterculture workshops

Murphy and Price were assisted by Spiegelberg, Watts, Huxley and his wife Laura, as well as by Gerald Heard and Gregory Bateson. They modeled the concept of Esalen partially upon Trabuco College, founded by Heard as a quasi-monastic experiment in the mountains east of Irvine, California, and later donated to the Vedanta Society.[26] Their intent was to provide "a forum to bring together a wide variety of approaches to enhancement of the human potential... including experiential sessions involving encounter groups, sensory awakening, gestalt awareness training, related disciplines."[27][28]

Alan Watts gave the first lecture at Esalen in January 1962.[29] Gia-fu Feng joined Price and Murphy,[30] along with Bob Breckenridge, Bob Nash, Alice and Jim Sellers, as the first Esalen staff members.[22] In the middle of that same year Abraham Maslow, a prominent humanistic psychologist, just happened to drive into the grounds and soon became an important figure at the institute.[31] In the fall of 1962, they published a catalog advertising workshops with such titles as "Individual and Cultural Definitions of Rationality", "The Expanding Vision" and "Drug-Induced Mysticism".[29] Their first seminar series in the fall of 1962 was "The Human Potentiality, based on a lecture by Huxley.[3]

Fritz Perls residency

In 1964, Fritz Perls began what became a five-year long residency at Esalen, leaving a lasting influence. Perls offered many Gestalt therapy seminars at the institute until he left in July 1969.[32] Jim Simkin[33] and Perls led Gestalt training courses at Esalen. Simkin started a Gestalt training center[34] on property next door that was later incorporated into Esalen’s main campus.[35]

When Perls left Esalen he considered it to be "in crisis again". He saw young people without any training leading encounter groups. And he feared that charlatans would take the lead.[36] However, Grogan claims that Perls’ practice at Esalen had been ethically “questionable”,[37] and according to Kripal, Perls insulted Abraham Maslow.[38]

Gestalt Practice developed

Dick Price became one of Perls' closest students. Price managed the Institute and developed his own form he called Gestalt Practice,[39] which he taught at Esalen until his death in a hiking accident in 1985.[40] Michael Murphy lived in the San Francisco Francisco Bay Area and wrote non-fiction books about Esalen-related topics, as well as several novels.[41]

Leads counterculture movement

Esalen gained popularity quickly and started to regularly publish catalogs full of programs. The facility was large enough to run multiple programs simultaneously, so Esalen created numerous resident teacher positions.[42] Murphy recruited Will Schutz, the well-known encounter group leader, to take up permanent residence at Esalen.[43] All this combined to firmly position Esalen in the nexus of the counterculture of the 1960s.

The institute gained increased attention in 1966 when several magazines wrote about it. George Leonard published an article in Look magazine about the California scene which mentioned Esalen and included a picture of Murphy.[44] Time magazine published an article about Esalen in September 1967.[45] The New York Times Magazine published an article by Leo E. Litwak in late December.[46] Life also published an article about the resort.[47] These articles increased the media and the public's awareness of the institute in the U.S. and abroad. Esalen responded by holding large-scale conferences in Midwestern and East Coast cities,[48] as well as in Europe. Esalen opened a satellite center in San Francisco that offered extensive programming until it closed in the mid-1970s for financial reasons.[49]

Programs and management

The institute continues to offer workshops about humanistic psychology, physical wellness, and spiritual awareness. The institute has also added workshops on permaculture and ecological sustainability.[50] Other workshops cover a wide range of subjects including arts, health, Gestalt, integral thought, martial arts, massage, dance, mythology, philosophical inquiry, somatics, spiritual and religious studies, ecopsychology, wilderness experience, yoga, tai chi, mindfulness practice, and meditation.

Center for Theory and Research

In 1998, Esalen launched the Center for Theory and Research to initiate new areas of practice and action which foster social change and realization of the human potential.[51] It is the research and development arm of Esalen Institute.[52] As of 2016, Michael Cornwall, who previously worked in the Institutes' Schizophrenia Research Project at Agnews State Hospital, was conducting workshops titled the Alternative Views and Approaches to Psychosis Initiative at Esalen. He was inviting leaders in the field of psychosis treatment to attend the workshops.[53]

Management changes

Esalen has been making changes to respond to internal and external factors.[54][55][56] Dick Price was the key leader of the institute until his sudden death in a hiking accident in late 1985 brought about many changes in personnel and programming.[57] Steven Donovan became president of the institute,[58] and Brian Lyke served as general manager.[57] Nancy Lunney became the director of programming,[59] and Dick Price's son David Price served as general manager of Esalen beginning in the mid-1990s.[60]

The baths were destroyed in 1998 by severe weather and were rebuilt at great expense, but this caused severe institutional stress.[61] Afterward, Andy Nusbaum developed an economic plan to stabilize Esalen's finances.[62]

In 2011, the Institute commissioned the company Beyond the Leading Edge to conduct a Leadership Culture Survey to assess the quality of its leadership culture. The results were negative. The survey measured how well the leadership "builds quality relationships, fosters teamwork, collaborates, develops people, involves people in decision making and planning, and demonstrates a high level of interpersonal skill." In the "relating dimension" the survey returned a score of 18%, compared to a desired 88%. It also produced strongly dissonant scores in measures of community welfare, relating with interpersonal intelligence, clearly communicating vision, and building a sense of personal worth within the community. It ranked management as overly compliant and lacking authenticity. However, the survey found that Esalen closely matched its overall goal for customer focus.[63]

Gordon Wheeler dramatically restructured Esalen management.[64] These changes prompted Christine Stewart Price, the widow of Dick Price, to withdraw from the institute, and found an organization named the Tribal Ground Circle with the intention to preserve Dick Price's legacy.[65][66]

Early leaders and programs

In the few years after its founding, many of the seminars[67] like the "The Value of Psychotic Experience" attempted to challenge the status quo. There were even Esalen programs that questioned the movement of which Esalen itself was a part — for instance, "Spiritual and Therapeutic Tyranny: The Willingness To Submit". There were also a series of encounter groups focused on racial prejudice.[68]

Early leaders included many well-known individuals, including Ansel Adams, Gia-fu Feng, Buckminster Fuller, Timothy Leary, Robert Nadeau, Linus Pauling, Carl Rogers, Virginia Satir, B.F Skinner, and Arnold Toynbee. Rather than merely lecturing, many leaders experimented with what Huxley called the non-verbal humanities: the education of the body, the senses, and the emotions. Their intention was to help individuals develop awareness of their present flow of experience, to express this fully and accurately, and to listen to feedback. These "experiential" workshops were particularly well attended and were influential in shaping Esalen's future course.[69]

Staff residency

Because of Esalen's isolated location, its operational staff members have lived on site from the beginning and for many years collectively contributed to the character of the institute.[70] The community has been steeped in a form of Gestalt that pervades all aspects of daily life, including meeting structures, workplace practices, and individual language styles.[71] There is a preschool on site called the Gazebo, serving the children of staff, some program participants, and affiliated local residents.[72]

Scholars in residence

Esalen has sponsored long-term resident scholars, including notable individuals such as Gregory Bateson, Joseph Campbell, Stanislav Grof, Sam Keen, George Leonard, Fritz Perls, Ida Rolf, Virginia Satir, William Schutz, and Alan Watts.

Esalen Massage and Bodywork Association

Bodywork has always been a significant part of the Esalen experience. In the late 1990s, the "EMBA" was organized as a semi-autonomous Esalen association for the regulation of Esalen massage practitioners.[73]

Past initiatives and projects

Esalen Institute has sponsored many research initiatives, educational projects, and invitational conferences. The Big Sur facility has been used for these events, as well as other locations, including international sites.

Arts events

In 1964, Joan Baez led a workshop entitled "The New Folk Music"[74] which included a free performance. This was the first of seven "Big Sur Folk Festivals" featuring many of the era's music legends. The 1969 concert included musicians who had just come from the Woodstock Festival. This event was featured in a documentary movie, Celebration at Big Sur, which was released in 1971.

John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg performed together at Esalen. Robert Bly, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, Kenneth Rexroth (who led one of the first workshops), Gary Snyder and others held poetry readings and workshops.

In 1994, President and CEO Sharon Thom[75] created an artist-in-residence program to provide artists with a two-week retreat in which to focus upon works in progress. These artists interacted with the staff, offered informal gatherings, and staged performances on the newly created dance platform. Located next to the Art Barn, the dance platform was used by Esalen teachers for dance and martial arts. The platform was later covered by a dome and renamed the Leonard Pavilion after deceased Esalen past president and board member, George Leonard.

In 1995 and 1996, Esalen hosted two arts festivals which gathered together artists, poets, musicians, photographers and performers, including artist Margot McLean, psychotherapist James Hillman, guitarist Michael Hedges and Joan Baez. All staff members were allowed to attend every class and performance that did not interfere with their schedules. Arts festivals have since become a popular yearly event at Esalen.[76]

Schizophrenia Research Project

Encouraged by Dick Price, the Schizophrenia Research Project was conducted over a three-year period at Agnews State Hospital in San Jose, California, involving 80 young males diagnosed with schizophrenia.[77] Funded in part by Esalen Institute, this program was co-sponsored by the California Department of Mental Hygiene (reorganized: CMHSA) and the National Institute of Mental Health. It explored the thesis that the health of certain patients would permanently improve if their psychotic process was not interrupted by administration of antipsychotic pharmaceutical drugs.[78] Julian Silverman was chief of research for the project. He also served as Esalen's general manager in the 1970s.[79] The Agnews double blind study was the largest first-episode psychosis research project ever conducted in the United States. It demonstrated that the young men given a placebo had a 75 percent lower re-hospitalization rate and much better outcomes than the men who received anti-psychotic medication. These results were used as justification for medication-free programs in the San Francisco Bay Area.[80]

Publishing

Starting in 1969, in association with Viking Press, the institute published a series of 17 books about Esalen-related topics, including the first edition of Michael Murphy's novel, Golf in the Kingdom (1971).[81] Some of these books remain in print.

In the mid-1980s, Esalen entered into a joint publishing arrangement with Lindisfarne Press to publish a small library of Russian philosophical and theological books.[82]

Soviet-American Exchange Program

In 1980, Esalen began the Soviet-American Exchange Program (later renamed: Track Two, an institute for citizen diplomacy).[83] This initiative came at a time when Cold War tensions were at their peak. The program was credited with substantial success in fostering peaceful private exchanges between citizens of the "super powers".[84] In the 1980s, Michael Murphy and his wife Dulce were instrumental in organizing the program with Soviet citizen Joseph Goldin, in order to provide a vehicle for citizen-to-citizen relations between Russians and Americans. In 1982, Esalen and Goldin pioneered the first U.S.–Soviet Space Bridge, allowing Soviet and American citizens to speak directly with one another via satellite communication. In 1988, Esalen brought Abel Aganbegyan, one of Mikhail Gorbachev's chief economic advisors, to the United States. In 1989, Esalen brought Boris Yeltsin on his first trip to the United States, although Yeltsin did not visit the Esalen facility in Big Sur. Esalen arranged meetings for Yeltsin with then President George H. W. Bush as well as many other leaders in business and government. Two former presidents of the exchange program included Jim Garrison and Jim Hickman. After Gorbachev stepped down, and effectively dissolved the Soviet Union, Garrison helped establish The State of the World Forum, with Gorbachev as its convening chairman. These successes led to other Esalen citizen diplomacy programs, including exchanges with China, an initiative to further understanding among Jews, Christians and Muslims, as well as further work on Russian-American relations.[85]

Cultural influence and legacy

Esalen has been cited as having played a key role in the cultural transformations of the 1960s.[86] In its beginnings as a "laboratory for new thought", it was seen by some as the headquarters of the human potential movement.[87] Its use of encounter groups, a focus on the mind-body connection, and their ongoing experimentation in personal awareness introduced many ideas to American society that later became mainstream.[3] In its early years, guest lecturers and workshop leaders included many leading thinkers, psychologists, and philosophers including Erik Erikson, Ken Kesey, Alan Watts, John Lilly, Buckminster Fuller, Aldous Huxley, Linus Pauling, Fritz Perl, Joseph Campbell, Robert Bly and Carl Rogers.[88]

Esalen has also been the subject of some criticism and controversy.[89] The Economist wrote, “For many others in America and around the world, Esalen stands more vaguely for that metaphorical point where ‘East meets West’ and is transformed into something uniquely and mystically American or New Agey. And for a great many others yet, Esalen is simply that notorious bagno-bordello where people had sex and got high throughout the 1960s and 1970s before coming home talking psychobabble and dangling crystals.”[6] Other criticism may be found in publications cited in the footnotes.[90][91][92]

The Human Potential Movement was criticized for espousing an ethic that the inner-self should be freely expressed in order to reach a person's true potential. Some people saw this ethic as an aspect of Esalen's culture. The historian Christopher Lasch claimed that humanistic techniques encourage narcissistic, spiritual materialistic or self-obsessive thoughts and behaviors.[93] In 1990 a graffiti artist spray painted "Jive shit for rich white folk" on the entrance to Esalen,[70] highlighting class and race issues. Some thought that this was a regression of progress away from true spiritual growth.[70]

Prices and finances

Attendance and costs

In 2012, 600 Esalen workshops were attended by more than 12,000 people. Topics ranged from sustainable business practices to hypnosis to "The Holy Fool: Crazy Wisdom From Van Gogh to Tina Fey and The Big Lebowski."[19]

As of 2015, a weekend workshop, including the program, meals, and a place for a sleeping bag in a communal area, cost a minimum of $405 per person. A couple could rent a private room for $730 per person. Week-long workshops begin at $900 and couples are charged $1,700 per person to stay in a private room.[94] In 2013, the Institute charges participants in its month-long, residential licensed massage practitioner training programs, $4910, including board and room.[95] In 1987, a weekend workshop along with a single room and meals cost $270, and a five-day workshop cost $530.[96]

Revenue and expenses

In 2013, the Institute reported revenue of $18,513,254, $13,066,407 from programs, and after expenses of $13,515,552 a net income of $4,997,702. In that year it paid CEO Patricia McEntee $152,077[97] In 2014, it reported total revenue of $15,934,586, expenses totalling $14,472,201, and net revenue of $1,462,385. McEntee was paid $157,839.[98]

Lease terms

The annual cost of its 87 year lease from the Vinnie A. Murphy Trust—which extends through 2049—was $344,704 in 2014. McEntee told the Monterey County Weekly that the cost of the lease is highly discounted, and that the terms of the lease allow the trust to re-assess the lease terms in 2017. This could potentially increase the Institute's rent to market value.[99]

Past teachers

Past guest teachers include:

- Ansel Adams

- Joan Baez

- Ellen Bass

- Robert Bly

- Gregory Bateson

- Ray Bradbury

- Joseph Campbell

- Fritjof Capra

- Carlos Castaneda

- Deepak Chopra

- Phil Cousineau

- Harvey Cox

- David Darling

- Erik Davis

- Warren Farrell

- Moshe Feldenkrais

- Richard Feynman

- Matthew Fox

- Fred Frith

- Betty Fuller[100][101][102]

- Buckminster Fuller

- Spalding Gray

- Stanislav Grof

- Michael Harner

- Andrew Harvey

- John Heider[103][104][105][106]

- Paul Horn

- Chungliang Al Huang

- James Hillman

- Albert Hofmann

- Aldous Huxley

- Sam Keen

- Ken Kesey

- Paul Krassner

- R. D. Laing

- George Leonard

- Dennis Lewis

- John C. Lilly

- Amory Lovins

- Abraham Maslow

- Peter Matthiessen

- Rollo May

- Terence McKenna

- Robert Nadeau

- Claudio Naranjo

- Sara Nelson

- Babatunde Olatunji

- Dean Ornish

- Humphry Osmond

- Linus Pauling

- Fritz Perls

- J. B. Rhine

- Carl Rogers

- Ida Rolf

- Gabrielle Roth

- Jerry Rubin

- Douglas Rushkoff

- Virginia Satir

- Will Schutz

- Charlotte Selver

- B.F. Skinner

- Huston Smith

- Gary Snyder

- Susan Sontag

- David Steindl-Rast

- Paul Tillich

- Arnold J. Toynbee

- George Vithoulkas

- Alan Watts

- Robert Anton Wilson

- Andrew Weil

- Marion Woodman

In popular culture

.jpg)

Esalen has been the subject of loose interpretations in art, entertainment, and media.

In the comedy-drama Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969), sophisticated Los Angeles residents Bob and Carol Sanders (played by Robert Culp and Natalie Wood) spend a weekend of emotional honesty at an Esalen-style retreat,[107] after which they return to their life determined to embrace free love and complete openness.

In "What About Bob?" (1991) Bill Murray's character mentions that he hasn't felt this good since Esalen upon his arrival at his psychiatrist's vacation home.

Esalen features prominently in Edward St Aubyn's comic novel On the Edge (1998).

A BBC television series, The Century of the Self (2002), was critical of the Human Potentials Movement and included video segments recorded at Esalen.[108]

The Mad Men finale, "Person to Person" (which aired on May 17, 2015), featured Don and Stephanie staying at an Esalen-like coastline retreat in the year 1970.[109]

The Panticapaeum Institute from True Detective Season 2 was largely based on the Esalen Institute.[110]

The Chryskylodon Institute, from Thomas Pynchon's Inherent Vice and Paul Thomas Anderson's film adaptation, is modeled after Esalen.[111]

Michel Houellebecq's Atomised traces the New Age movement's influence on the novel's protagonists to older generations' chance meetings at Esalen.

References

Notes

- ↑ "Contact Us".

- ↑ Goldman 2012, pp. 2–

- 1 2 3 Misiroglu, Gina, ed. (2009). American Countercultures: An Encyclopedia of Nonconformists, Alternative Lifestyles, and Radical Ideas in U.S. History. Armonk, N.Y.: Sharpe Reference. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-0765680600. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ Kripal, Jeffrey J. (15 April 2007). "Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion". University of Chicago Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 64

- 1 2 "Where 'California' bubbled up". The Economist. 19 December 2007.

- ↑ "Esalen Institute Launches Campus Renewal with Special Gift for Most Significant Renovation in 52-year History". May 15, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ Kripal 2007

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 30

- ↑ Documentation provided by Steven Harper of radiocarbon dating, performed by members of the Sonoma State University Cultural Resources Faculty, that produced the following results: 4,630 +/- 100 years BP (before present). Harper notes confirmation by similar tests from Big Creek (4-5 miles south of Esalen Institute), which produced: 6,400 years BP, as cited in The Prehistory of Big Creek by Terry Jones (2000).

- ↑ "Thomas B Slate, Patent #CACAAA-092028". The Land Patents. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 32

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 95

- ↑ Goldman 2012, p. 56

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 60

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 47 et seq

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 48

- ↑ "Dick Price: An Interview". Esalen. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Hockaday, Peter (May 18, 2015). "Hippies, nudity, and Don Draper: Inside Big Sur's Esalen Institute featured in 'Mad Men'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ↑ "John Andrew Murphy", United States Census, 1940; Salinas, California; roll T627_267, page 19A,, enumeration district 27-5, Family History film 715. Retrieved on August 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Michigan Births and Christenings, 1775–1995". Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch. 2009–2010.

- 1 2 Kripal 2007, p. 98

- ↑ Kripal & Shuck 2005, p. 148

- ↑ Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, Calif.: Word Dancer Press. p. 960. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- ↑ Goldman 2012, p. 19

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 91

- ↑ The Aquarian Conspiracy

- ↑ The Mother of All Webs Who Gotcha! Gyeorgos C. Hatonn. page 211

- 1 2 Anderson 2004, p. 65

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 63

- ↑ Kripal & Shuck 2005, p. 2

- ↑ Perls 1992

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 175

- ↑ Fadul 2014, p. 204 Encyclopedia of Theory & Practice in Psychotherapy & Counseling

- ↑ Leyde, Tom (March 20, 2015). "Esalen Institute to get a face lift". Santa Cruz Sentinel : Architecture, March 20, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ↑ Perls 1992, p. 249

- ↑ Grogan 2008, p. 196

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 157

- ↑ Callahan 2014

- ↑ The Only Way Out Is In: The Life Of Richard Price Barclay James Erickson, in Kripal & Shuck 2005

- ↑ Kripal 2007, pp. 274, 291–2

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 151

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 156

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 207

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 160

- ↑ Litwak, Leo E. (December 31, 1967). "A Trip to Esalen Institute -- Joy Is the Prize". The New York Times Magazine. pp. 119 et seq. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 172

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 219

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 181 et seq

- ↑ "The Esalen Farm & Garden: Cultivating Soil, Plants and People".

- ↑ Esalen Center for Theory and Research.

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 439

- ↑ Alternative Views and Approaches to Psychosis, November 2012. An Esalen Center For Theory and Research Initiative at Esalen Institute.

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 147 et seq

- ↑ Goldman 2012, p. 44

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 463

- 1 2 Kripal 2007, p. 389

- ↑ Goldman 2012, p. 65

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 376

- ↑ Goldman 2012, pp. 107ff

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 436

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 437

- ↑ "Leadership Culture Survey Online Summary". Esalen Leadership. Archived from the original on 29 Jul 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ Goldman 2012, p. 44

- ↑ Goldman 2012, p. 65

- ↑ "Tribal Ground Circle". Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ↑ Kripal 2007, pp. 101 et seq

- ↑ Kripal 2007, pp. 182 et seq

- ↑ Kripal 2007, pp. 104

- 1 2 3 Kripal 2007, p. 401

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 172

- ↑ "Gazebo School Park Early Childhood Program".

- ↑ Goldman 2012, p. 67

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 102

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 434

- ↑ "EsalenArtsFestival2011".

- ↑ Anderson 2004, pp. 217–219

- ↑ Rappaport, M. "Are There Schizophrenics for Whom Drugs May be Unnecessary or Contraindicated?" International Pharmacopsychiatry 13 (1978) p. 100 et seq.

- ↑ "Julian Silverman".

- ↑ Cornwall 2002, p. 4

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 527

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 320

- ↑ "Track II (Citizen) Diplomacy" at The Beyond Intractability Knowledge Base Project.

- ↑ Track Two, An Institute For Citizen Diplomacy.

- ↑ Esalen CTR: Accomplishments in Citizen Diplomacy.

- ↑ "40 years later, Woodstock's spiritual vibes still resonate", Houston Chronicle. August 6, 2009.

- ↑ Martin, Douglas (January 19, 2010). "George Leonard, 86, voice of '60s counterculture - The Boston Globe". archive.boston.com. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ Large, Writer at (25 May 2012). Ollivier, Debra, ed. "Esalen: 50 Years Ago, A 'Crazy Place On A Godforsaken Road' Launched The New Age Movement". The Huffington Post. Huffington Post. Retrieved 20 October 2016. Missing

|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ "Esalen's Identity Crisis", Los Angeles Times Magazine. September 5, 2004.

- ↑ "Like countless spiritual pilgrims, Esalen Institute faces its own midlife crisis".

- ↑ Norimitsu Onishi (August 19, 2012). "Celebrating the Past, and Debating the Future". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ Kera Abraham and Mark Anderson. "One Half-Century at Esalen Institute". Monterey County Weekly. October 4, 2012.

- ↑ Lasch 1978, p. 13

- ↑ SHAPIRO, MICHAEL (December 31, 2015). "Getaways: Esalen Institute in Big Sur is a place to learn, grow and heal". Santa Rosa Press Democrat. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ↑ "Esalen Massage Practitioner Training Course Catalog" (PDF). Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ↑ Kahn, Alice (December 6, 1987). "Ways to 'Do' Esalen". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ↑ "2013 IRS Form 990" (PDF). Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ↑ "2014 IRS Form 990" (PDF). Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Esalen's a nonprofit, but a visit doesn't come cheap". October 4, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ Anderson 2004, pp. 159, 178, 179, 207, 220, 234, 253, 320

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 490

- ↑ Wildflower, Leni. The Hidden History Of Coaching, Open University Press (2013) p. 17

- ↑ Kripal 2007, p. 547 [listing numerous citations]

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 159

- ↑ Heider, John The Tao of Leadershp Green Dragon Publishing (2005)

- ↑ "John Heider".

- ↑ Anderson 2004, p. 140

- ↑ YouTube segments.

- ↑ Dean, Will (17 May 2015). "Mad Men recap: season seven, episode 14 – Person to Person (warning: spoilers)". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ↑ Caitlin Gallagher. "Is The Panticapaeum Institute From 'True Detective' A Real Place? Ani's Father's Retreat Resembles An Actual Facility". Bustle. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

...there is one real place that Vulture pointed out might have inspired both Mad Men and True Detective — and that's the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California.

- ↑ "The Southern California Landscape of Inherent Vice - Los Angeles Magazine". 12 December 2014.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Walter Truett (2004) [1983]. The Upstart Spring: Esalen and the Human Potential Movement: The First Twenty Years. Addison Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 0-595-30735-3.

- Callahan, John F., ed. (2014). Manual of Gestalt Practice in the Tradition of Dick Price. The Gestalt Legacy Project. ISBN 978-1-3049-6247-8.

- Cornwall, Michael W. (2002). Alternative Treatment of Psychosis, A Dissertation presented at the California Institute of Integral Studies (PDF). San Francisco, CA.

- Fadul, Jose A., ed. (2014). Encyclopedia of Theory & Practice in Psychotherapy & Counseling. Lulu Press.

- Goldman, Marion S. (2012). The American Soul Rush: Esalen and the Rise of Spiritual Privilege. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3287-8.

- Grogan, Jessica Lynn (2008). A Cultural History of the Humanistic Psychology Movement (PDF). The University of Texas at Austin.

- Kripal, Jeffrey (2007). Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45369-3.

- Kripal, Jeffrey; Shuck, Glenn W., eds. (2005). On The Edge Of The Future: Esalen And The Evolution Of American Culture. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21759-8.

- Lasch, C. (1978). The Culture of Narcissism. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Perls, Frederick (1992). In and Out of the Garbage Pail. Real People Press [1969]; Gestalt Journal Press. ISBN 978-0-939266-17-3.

Further reading

- Callahan, John F., ed. (2014). The Life and Practice of Richard Price. The Gestalt Legacy Project. ISBN 978-1-312-06228-3.

- Lattin, Don (2004). Following Our Bliss : How the Spiritual Ideals of the Sixties Shape Our Lives Today. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-009394-3.

- Norman, Jeff (2004). Big Sur. Images of America Series. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-2913-3.

- Miller, Stuart (1971). Hot Springs: The True Adventures of the First New York Jewish Literary Intellectual in the Human-Potential Movement. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-226-45369-3.

- Murphy, Michael (1971). Golf in the Kingdom. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-019549-1.

- Murphy, Michael (1992). The Future of the Body. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam. ISBN 0-14-019549-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Esalen Institute. |

- Esalen Institute website

- Notes on Gestalt Practice

- "In Murphy's Kingdom" article by Jackie Krentzman

- "Huxley on Huxley.". Dir. Mary Ann Braubach. Cinedigm, 2010. DVD.

- "Totally on Fire: The Experience of Founding Esalen" from Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion by Jeff Kripal