Permaculture

|

| Agriculture |

|---|

| History |

| Farming |

| Other types |

| Related |

| Lists |

| Categories |

|

|

|

Permaculture is a system of agricultural and social design principles centered on simulating or directly utilizing the patterns and features observed in natural ecosystems. Permaculture was developed, and the term coined by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren in 1978.[1]

It has many branches that include but are not limited to ecological design, ecological engineering, environmental design, construction and integrated water resources management that develops sustainable architecture, and regenerative and self-maintained habitat and agricultural systems modeled from natural ecosystems.[2][3]

Mollison has said: "Permaculture is a philosophy of working with, rather than against nature; of protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless labor; and of looking at plants and animals in all their functions, rather than treating any area as a single product system."[4]

History

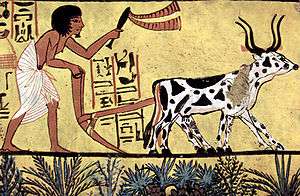

In 1929, Joseph Russell Smith took up an antecedent term as the subtitle for Tree Crops: A Permanent Agriculture, a book in which he summed up his long experience experimenting with fruits and nuts as crops for human food and animal feed.[5] Smith saw the world as an inter-related whole and suggested mixed systems of trees and crops underneath. This book inspired many individuals intent on making agriculture more sustainable, such as Toyohiko Kagawa who pioneered forest farming in Japan in the 1930s.[6]

The definition of permanent agriculture as that which can be sustained indefinitely was supported by Australian P. A. Yeomans in his 1964 book Water for Every Farm. Yeomans introduced an observation-based approach to land use in Australia in the 1940s, and the keyline design as a way of managing the supply and distribution of water in the 1950s.

Stewart Brand’s works were an early influence noted by Holmgren.[7] Other early influences include Ruth Stout and Esther Deans, who pioneered no-dig gardening, and Masanobu Fukuoka who, in the late 1930s in Japan, began advocating no-till orchards, gardens, and natural farming.[8]

In the late 1960s, Bill Mollison and David Holmgren started developing ideas about stable agricultural systems on the southern Australian island state of Tasmania. This was a result of the danger of the rapidly growing use of industrial-agricultural methods. In their view,[9] these methods were highly dependent on non-renewable resources, and were additionally poisoning land and water, reducing biodiversity, and removing billions of tons of topsoil from previously fertile landscapes. A design approach called permaculture was their response and was first made public with the publication of their book Permaculture One in 1978.[9]

By the early 1980s, the concept had broadened from agricultural systems design towards sustainable human habitats. After Permaculture One, Mollison further refined and developed the ideas by designing hundreds of permaculture sites and writing more detailed books, notably Permaculture: A Designers Manual. Mollison lectured in over 80 countries and taught his two-week Permaculture Design Course (PDC) to many hundreds of students. Mollison "encouraged graduates to become teachers themselves and set up their own institutes and demonstration sites. This multiplier effect was critical to permaculture’s rapid expansion."[10]

Core tenets and principles of design

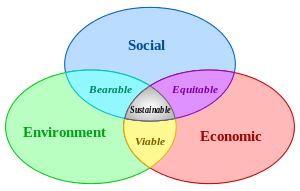

The three core tenets of permaculture are:[11][12][13]

- Care for the earth: Provision for all life systems to continue and multiply. This is the first principle, because without a healthy earth, humans cannot flourish.

- Care for the people: Provision for people to access those resources necessary for their existence.

- Return of surplus: Reinvesting surpluses back into the system to provide for the first two ethics. This includes returning waste back into the system to recycle into usefulness.[14] The third ethic is sometimes referred to as Fair Share to reflect that each of us should take no more than what we need before we reinvest the surplus.

Permaculture design emphasizes patterns of landscape, function, and species assemblies. It determines where these elements should be placed so they can provide maximum benefit to the local environment. The central concept of permaculture is maximizing useful connections between components and synergy of the final design. The focus of permaculture, therefore, is not on each separate element, but rather on the relationships created among elements by the way they are placed together; the whole becoming greater than the sum of its parts. Permaculture design therefore seeks to minimize waste, human labor, and energy input by building systems with maximal benefits between design elements to achieve a high level of synergy. Permaculture designs evolve over time by taking into account these relationships and elements and can become extremely complex systems that produce a high density of food and materials with minimal input.[15]

The design principles which are the conceptual foundation of permaculture were derived from the science of systems ecology and study of pre-industrial examples of sustainable land use. Permaculture draws from several disciplines including organic farming, agroforestry, integrated farming, sustainable development, and applied ecology.[16] Permaculture has been applied most commonly to the design of housing and landscaping, integrating techniques such as agroforestry, natural building, and rainwater harvesting within the context of permaculture design principles and theory.

Theory

Twelve design principles

Twelve Permaculture design principles articulated by David Holmgren in his Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability:[17]

- Observe and interact: By taking time to engage with nature we can design solutions that suit our particular situation.

- Catch and store energy: By developing systems that collect resources at peak abundance, we can use them in times of need.

- Obtain a yield: Ensure that you are getting truly useful rewards as part of the work that you are doing.

- Apply self-regulation and accept feedback: We need to discourage inappropriate activity to ensure that systems can continue to function well.

- Use and value renewable resources and services: Make the best use of nature's abundance to reduce our consumptive behavior and dependence on non-renewable resources.

- Produce no waste: By valuing and making use of all the resources that are available to us, nothing goes to waste.

- Design from patterns to details: By stepping back, we can observe patterns in nature and society. These can form the backbone of our designs, with the details filled in as we go.

- Integrate rather than segregate: By putting the right things in the right place, relationships develop between those things and they work together to support each other.

- Use small and slow solutions: Small and slow systems are easier to maintain than big ones, making better use of local resources and producing more sustainable outcomes.

- Use and value diversity: Diversity reduces vulnerability to a variety of threats and takes advantage of the unique nature of the environment in which it resides.

- Use edges and value the marginal: The interface between things is where the most interesting events take place. These are often the most valuable, diverse and productive elements in the system.

- Creatively use and respond to change: We can have a positive impact on inevitable change by carefully observing, and then intervening at the right time.

Layers

Layers are one of the tools used to design functional ecosystems that are both sustainable and of direct benefit to humans. A mature ecosystem has a huge number of relationships between its component parts: trees, understory, ground cover, soil, fungi, insects, and animals. Because plants grow to different heights, a diverse community of life is able to grow in a relatively small space, as the vegetation occupies different layers. There are generally seven recognized layers in a food forest, although some practitioners also include fungi as an eighth layer.[18]

- The canopy: the tallest trees in the system. Large trees dominate but typically do not saturate the area, i.e. there exist patches barren of trees.

- Understory layer: trees that revel in the dappled light under the canopy.

- Shrub layer: a diverse layer of woody perennials of limited height. includes most berry bushes.

- Herbaceous layer: Plants in this layer die back to the ground every winter (if winters are cold enough, that is). They do not produce woody stems as the Shrub layer does. Many culinary and medicinal herbs are in this layer. A large variety of beneficial plants fall into this layer. May be annuals, biennials or perennials.

- Soil surface/Groundcover: There is some overlap with the Herbaceous layer and the Groundcover layer; however plants in this layer grow much closer to the ground, grow densely to fill bare patches of soil, and often can tolerate some foot traffic. Cover crops retain soil and lessen erosion, along with green manures that add nutrients and organic matter to the soil, especially nitrogen.

- Rhizosphere: Root layers within the soil. The major components of this layer are the soil and the organisms that live within it such as plant roots (including root crops such as potatoes and other edible tubers), fungi, insects, nematodes, worms, etc.

- Vertical layer: climbers or vines, such as runner beans and lima beans (vine varieties).[18][19]

Guilds

There are many forms of guilds, including guilds of plants with similar functions (that could interchange within an ecosystem), but the most common perception is that of a mutual support guild. Such a guild is a group of species where each provides a unique set of diverse functions that work in conjunction, or harmony. Mutual support guilds are groups of plants, animals, insects, etc. that work well together. Some plants may be grown for food production, some have tap roots that draw nutrients up from deep in the soil, some are nitrogen-fixing legumes, some attract beneficial insects, and others repel harmful insects. When grouped together in a mutually beneficial arrangement, these plants form a guild. See Dave Jacke's work on edible forest gardens for more information on other guilds, specifically resource-partitioning and community-function guilds.[20][21][22]

Edge effect

The edge effect in ecology is the effect of the juxtaposition or placing side by side of contrasting environments on an ecosystem. Permaculturists argue that, where vastly differing systems meet, there is an intense area of productivity and useful connections. An example of this is the coast; where the land and the sea meet there is a particularly rich area that meets a disproportionate percentage of human and animal needs. So this idea is played out in permacultural designs by using spirals in the herb garden or creating ponds that have wavy undulating shorelines rather than a simple circle or oval (thereby increasing the amount of edge for a given area).

Zones

Zones are a way of intelligently organizing design elements in a human environment on the basis of the frequency of human use and plant or animal needs. Frequently manipulated or harvested elements of the design are located close to the house in zones 1 and 2. Less frequently used or manipulated elements, and elements that benefit from isolation (such as wild species) are farther away. Zones are about positioning things appropriately, and are numbered from 0 to 5.[23]

- Zone 0

- The house, or home center. Here permaculture principles would be applied in terms of aiming to reduce energy and water needs, harnessing natural resources such as sunlight, and generally creating a harmonious, sustainable environment in which to live and work. Zone 0 is an informal designation, which is not specifically defined in Bill Mollison’s book.

- Zone 1

- The zone nearest to the house, the location for those elements in the system that require frequent attention, or that need to be visited often, such as salad crops, herb plants, soft fruit like strawberries or raspberries, greenhouse and cold frames, propagation area, worm compost bin for kitchen waste, etc. Raised beds are often used in zone 1 in urban areas.

- Zone 2

- This area is used for siting perennial plants that require less frequent maintenance, such as occasional weed control or pruning, including currant bushes and orchards, pumpkins, sweet potato, etc. This would also be a good place for beehives, larger scale composting bins, etc.

- Zone 3

- The area where main-crops are grown, both for domestic use and for trade purposes. After establishment, care and maintenance required are fairly minimal (provided mulches and similar things are used), such as watering or weed control maybe once a week.

- Zone 4

- A semi-wild area. This zone is mainly used for forage and collecting wild food as well as production of timber for construction or firewood.

- Zone 5

- A wilderness area. There is no human intervention in zone 5 apart from the observation of natural ecosystems and cycles. Through this zone we build up a natural reserve of bacteria, moulds and insects that can aid the zones above it.[24]

People and permaculture

Permaculture uses observation of nature to create regenerative systems, and the place where this has been most visible has been on the landscape. There has been a growing awareness though that firstly, there is the need to pay more attention to the peoplecare ethic, as it is often the dynamics of people that can interfere with projects, and secondly that the principles of permaculture can be used as effectively to create vibrant, healthy and productive people and communities as they have been in landscapes.

Domesticated animals

Domesticated animals are often incorporated into site design.[25]

Common practices

Agroforestry

Agroforestry is an integrated approach of using the interactive benefits from combining trees and shrubs with crops and/or livestock. It combines agricultural and forestry technologies to create more diverse, productive, profitable, healthy and sustainable land-use systems.[26] In agroforestry systems, trees or shrubs are intentionally used within agricultural systems, or non-timber forest products are cultured in forest settings.

Forest gardening is a term permaculturalists use to describe systems designed to mimic natural forests. Forest gardens, like other permaculture designs, incorporate processes and relationships that the designers understand to be valuable in natural ecosystems. The terms forest garden and food forest are used interchangeably in the permaculture literature. Numerous permaculturists are proponents of forest gardens, such as Graham Bell, Patrick Whitefield, Dave Jacke, Eric Toensmeier and Geoff Lawton. Bell started building his forest garden in 1991 and wrote the book The Permaculture Garden in 1995, Whitefield wrote the book How to Make a Forest Garden in 2002, Jacke and Toensmeier co-authored the two volume book set Edible Forest Gardening in 2005, and Lawton presented the film Establishing a Food Forest in 2008.[15][27][28]

Tree Gardens, such as Kandyan tree gardens, in South and Southeast Asia, are often hundreds of years old. Whether they derived initially from experiences of cultivation and forestry, as is the case in agroforestry, or whether they derived from an understanding of forest ecosystems, as is the case for permaculture systems, is not self-evident. Many studies of these systems, especially those that predate the term permaculture, consider these systems to be forms of agroforestry. Permaculturalists who include existing and ancient systems of polycropping with woody species as examples of food forests may obscure the distinction between permaculture and agroforestry.

Food forests and agroforestry are parallel approaches that sometimes lead to similar designs.

Hügelkultur

Hügelkultur is the practice of burying large volumes of wood to increase soil water retention. The porous structure of wood acts as a sponge when decomposing underground. During the rainy season, masses of buried wood can absorb enough water to sustain crops through the dry season.[29] This technique has been used by permaculturalists Sepp Holzer, Toby Hemenway, Paul Wheaton, and Masanobu Fukuoka.[30][31]

Natural building

A natural building involves a range of building systems and materials that place major emphasis on sustainability. Ways of achieving sustainability through natural building focus on durability and the use of minimally processed, plentiful or renewable resources, as well as those that, while recycled or salvaged, produce healthy living environments and maintain indoor air quality.

The basis of natural building is the need to lessen the environmental impact of buildings and other supporting systems, without sacrificing comfort, health, or aesthetics. To be more sustainable, natural building uses primarily abundantly available, renewable, reused, or recycled materials. In addition to relying on natural building materials, the emphasis on the architectural design is heightened. The orientation of a building, the utilization of local climate and site conditions, the emphasis on natural ventilation through design, fundamentally lessen operational costs and positively impact the environment. Building compactly and minimizing the ecological footprint is common, as are on-site handling of energy acquisition, on-site water capture, alternate sewage treatment, and water reuse.

Rainwater harvesting

Rainwater harvesting is the accumulating and storing of rainwater for reuse before it reaches the aquifer.[32] It has been used to provide drinking water, water for livestock, water for irrigation, as well as other typical uses. Rainwater collected from the roofs of houses and local institutions can make an important contribution to the availability of drinking water. It can supplement the subsoil water level and increase urban greenery. Water collected from the ground, sometimes from areas which are especially prepared for this purpose, is called stormwater harvesting.

Greywater is wastewater generated from domestic activities such as laundry, dishwashing, and bathing, which can be recycled on-site for uses such as landscape irrigation and constructed wetlands. Greywater is largely sterile, but not potable (drinkable). Greywater differs from water from the toilets, which is designated sewage or blackwater to indicate it contains human waste. Blackwater is septic or otherwise toxic and cannot easily be reused. There are, however, continuing efforts to make use of blackwater or human waste. The most notable is for composting through a process known as humanure; a combination of the words human and manure. Additionally, the methane in humanure can be collected and used similar to natural gas as a fuel, such as for heating or cooking, and is commonly referred to as biogas. Biogas can be harvested from the human waste and the remainder still used as humanure. Some of the simplest forms of humanure use include a composting toilet or an outhouse or dry bog surrounded by trees that are heavy feeders which can be coppiced for wood fuel. This process eliminates the use of a standard toilet with plumbing.

Sheet mulching

In agriculture and gardening, mulch is a protective cover placed over the soil. Any material or combination can be used as mulch, such as stones, leaves, cardboard, wood chips, gravel, etc., though in permaculture mulches of organic material are the most common because they perform more functions. These include absorbing rainfall, reducing evaporation, providing nutrients, increasing organic matter in the soil, feeding and creating habitat for soil organisms, suppressing weed growth and seed germination, moderating diurnal temperature swings, protecting against frost, and reducing erosion. Sheet mulching is an agricultural no-dig gardening technique that attempts to mimic natural processes occurring within forests. Sheet mulching mimics the leaf cover that is found on forest floors. When deployed properly and in combination with other Permacultural principles, it can generate healthy, productive and low maintenance ecosystems.[33][34]

Sheet mulch serves as a "nutrient bank," storing the nutrients contained in organic matter and slowly making these nutrients available to plants as the organic matter slowly and naturally breaks down. It also improves the soil by attracting and feeding earthworms, slaters and many other soil micro-organisms, as well as adding humus. Earthworms "till" the soil, and their worm castings are among the best fertilizers and soil conditioners. Sheet mulching can be used to reduce or eliminate undesirable plants by starving them of light, and can be more advantageous than using herbicide or other methods of control.

Intensive rotational grazing

Grazing has long been blamed for much of the destruction we see in the environment. However, it has been shown that when grazing is modeled after nature, the opposite effect can be seen.[35][36] Also known as cell grazing, managed intensive rotational grazing (MIRG) is a system of grazing in which ruminant and non-ruminant herds and/or flocks are regularly and systematically moved to fresh pasture, range, or forest with the intent to maximize the quality and quantity of forage growth. This disturbance is then followed by a period of rest which allows new growth. MIRG can be used with cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens, rabbits, geese, turkeys, ducks, and other animals depending on the natural ecological community that is being mimicked. Sepp Holzer and Joel Salatin have shown how the disturbance caused by the animals can be the spark needed to start ecological succession or prepare ground for planting. Allan Savory's holistic management technique has been likened to "a permaculture approach to rangeland management".[37][38] One variation on MIRG that is gaining rapid popularity is called eco-grazing. Often used to either control invasives or re-establish native species, in eco-grazing the primary purpose of the animals is to benefit the environment and the animals can be, but are not necessarily, used for meat, milk or fiber.[39][40][41][42][43][44][45]

Keyline design

Keyline design is a technique for maximizing beneficial use of water resources of a piece of land developed in Australia by farmer and engineer P. A. Yeomans. The Keyline refers to a specific topographic feature linked to water flow which is used in designing the drainage system of the site.[46]

Fruit tree management

Some proponents of permaculture advocate no, or limited, pruning. One advocate of this approach is Sepp Holzer who used the method in connection with Hügelkultur berms. He has successfully grown several varieties of fruiting trees at altitudes (approximately 9,000 feet (2,700 m)) far above their normal altitude, temperature, and snow load ranges. He notes that the Hügelkultur berms kept and/or generated enough heat to allow the roots to survive during alpine winter conditions. The point of having unpruned branches, he notes, was that the longer (more naturally formed) branches bend over under the snow load until they touched the ground, thus forming a natural arch against snow loads that would break a shorter, pruned, branch.

Masanobu Fukuoka, as part of early experiments on his family farm in Japan, experimented with no-pruning methods, noting that he ended up killing many fruit trees by simply letting them go, which made them become convoluted and tangled, and thus unhealthy.[47][48] Then he realised this is the difference between natural-form fruit trees and the process of change of tree form that results from abandoning previously-pruned unnatural fruit trees.[47][49] He concluded that the trees should be raised all their lives without pruning, so they form healthy and efficient branch patterns that follow their natural inclination. This is part of his implementation of the Tao-philosophy of Wú wéi translated in part as no-action (against nature), and he described it as no unnecessary pruning, nature farming or "do-nothing" farming, of fruit trees, distinct from non-intervention or literal no-pruning. He ultimately achieved yields comparable to or exceeding standard/intensive practices of using pruning and chemical fertilisation.[47][49][50]

Trademark and copyright issues

There has been contention over who, if anyone, controls legal rights to the word permaculture: is it trademarked or copyrighted? and if so, who holds the legal rights to the use of the word? For a long time Bill Mollison claimed to have copyrighted the word, and his books said on the copyright page, "The contents of this book and the word PERMACULTURE are copyright." These statements were largely accepted at face-value within the permaculture community. However, copyright law does not protect names, ideas, concepts, systems, or methods of doing something; it only protects the expression or the description of an idea, not the idea itself. Eventually Mollison acknowledged that he was mistaken and that no copyright protection existed for the word permaculture.[51]

In 2000, Mollison's US based Permaculture Institute sought a service mark (a form of trademark) for the word permaculture when used in educational services such as conducting classes, seminars, or workshops.[52] The service mark would have allowed Mollison and his two Permaculture Institutes (one in the US and one in Australia) to set enforceable guidelines regarding how permaculture could be taught and who could teach it, particularly with relation to the PDC, despite the fact that he had instituted a system of certification of teachers to teach the PDC in 1993. The service mark failed and was abandoned in 2001. Also in 2001 Mollison applied for trademarks in Australia for the terms "Permaculture Design Course"[53] and "Permaculture Design".[53] These applications were both withdrawn in 2003. In 2009 he sought a trademark for "Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual"[53] and "Introduction to Permaculture",[53] the names of two of his books. These applications were withdrawn in 2011. There has never been a trademark for the word permaculture in Australia.[53]

Criticisms

General criticisms

In 2011, Owen Hablutzel argued that "permaculture has yet to gain a large amount of specific mainstream scientific acceptance," and that "the sensitiveness to being perceived and accepted on scientific terms is motivated in part by a desire for permaculture to expand and become increasingly relevant."

In his books Sustainable Freshwater Aquaculture and Farming in Ponds and Dams, Nick Romanowski expresses the view that the presentation of aquaculture in Bill Mollison's books is unrealistic and misleading.[54]

Agroforestry

Greg Williams argues that forests cannot be more productive than farmland because the net productivity of forests decline as they mature due to ecological succession.[55] Proponents of permaculture respond that this is true only if one compares data between woodland forest and climax vegetation, but not when comparing farmland vegetation with woodland forest. For example, ecological succession generally results in a forest's productivity rising after its establishment only until it reaches the woodland state (67% tree cover), before declining until full maturity.[15]

See also

- Agrarianism

- Agroecology

- Agroforestry

- Aquaponics

- Biodynamics

- Bill Mollison

- Biointensive agriculture

- Biomimicry

- Climate-friendly gardening

- David Holmgren

- Ecoagriculture

- Food-feed system

- Forest gardening

- Geoff Lawton

- Holzer Permaculture

- Hügelkultur

- List of permaculture projects

- Microponics

- Paul Wheaton

- Permaforestry

- Regenerative agriculture

- Seed saving

- Sepp Holzer

- Zaï

References

- ↑ Introduction to Permaculture, (1991), Mollison, p. v

- ↑ Hemenway 2009, p. 5.

- ↑ Mars, Ross (2005). The Basics of Permaculture Design. Chelsea Green. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-85623-023-0.

- ↑ Mollison, B. (1991). Introduction to permaculture. Tasmania, Australia: Tagari.

- ↑ Smith, Joseph Russell; Smith, John (1987). Tree Crops: A permanent agriculture. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-59726873-8.

- ↑ Hart 1996, p. 41.

- ↑ Holmgren, David (2006). "The Essence of Permaculture". Holmgren Design Services. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ↑ Mollison, Bill (September 15–21, 1978). "The One-Straw Revolution by Masanobu Fukuoka". Nation Review. p. 18.

- 1 2 Introduction to Permaculture, 1991, Mollison, p.v

- ↑ Lillington, Ian; Holmgren, David; Francis, Robyn; Rosenfeldt, Robyn. "The Permaculture Story: From 'Rugged Individuals' to a Million Member Movement" (PDF). Pip Magazine. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Greenblott, Kara; Nordin, Kristof (2012), Permaculture Design for Orphans and Vulnerable Children Programming: Low-Cost, Sustainable Solutions for Food and Nutrition Insecure Communities, AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources, AIDSTAR-One (Task Order 1), Arlington, VA: USAID.

- ↑ Mollison 1988, p. 2.

- ↑ Holmgren, David (2002). Permaculture: Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability. Holmgren Design Services. p. 1. ISBN 0-646-41844-0.

- ↑ Mollison, Bill. "Permaculture: A Quiet Revolution". Scott London (interview). Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Edible Forest Gardening".

- ↑ Holmgren, David (1997). "Weeds or Wild Nature" (PDF). Permaculture International Journal. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ↑ "Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability". Holmgren Design. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- 1 2 Nine layers of the edible forest garden, TC permaculture, May 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Seven layers of a forest", Food forests, CA: Permaculture school.

- ↑ Simberloff, D; Dayan, T (1991). "The Guild Concept and the Structure of Ecological Communities". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 22: 115. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.22.110191.000555.

- ↑ "Guilds". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ Williams, SE; Hero, JM (1998). "Rainforest frogs of the Australian Wet Tropics: guild classification and the ecological similarity of declining species". Proceedings. Biological sciences. The Royal Society. 265 (1396): 597–602. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0336. PMC 1689015

. PMID 9881468.

. PMID 9881468. - ↑ Burnett 2001.

- ↑ Permacultuur course, NL: WUR.

- ↑ Mollison 1988, p. 5: ‘Deer, rabbits, sheep, and herbivorous fish are very useful to us, in that they convert unusable herbage to acceptable human food. Animals represent a valid method of storing inedible vegetation as food.’

- ↑ "USDA National Agroforestry Center (NAC)". UNL. 2011-08-01. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ "Graham Bell's Forest Garden". Permaculture. Media mice.

- ↑ "Establishing a Food Forest" (film review). Transition culture. Feb 11, 2009.

- ↑ Wheaton, Paul. "Raised garden beds: hugelkultur instead of irrigation" Richsoil. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ↑ Hemenway 2009, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Feineigle, Mark. "Hugelkultur: Composting Whole Trees With Ease". Permaculture Research Institute of Australia. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ↑ "Rainwater harvesting". DE: Aramo. 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ "Sheet Mulching: Greater Plant and Soil Health for Less Work". Agroforestry. 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ Mason, J (2003), Sustainable Agriculture, Landlinks.

- ↑ "Prince Charles sends a message to IUCN's World Conservation Congress". International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ Undersander, Dan; et al. "Grassland birds: Fostering habitat using rotational grazing" (PDF). University of Wisconsin-Extension. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ Fairlie, Simon (2010). Meat: A Benign Extravagance. Chelsea Green. pp. 191–93. ISBN 978-1-60358325-1.

- ↑ Bradley, Kirsten. "Holistic Management: Herbivores, Hats, and Hope". Milkwood. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ↑ "Munching sheep replace lawn mowers in Paris". The Sunday Times. Apr 4, 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Ash, Andrew, The Ecograze Project – developing guidelines to better manage grazing country (PDF), et al., CSIRO, ISBN 0-9579842-0-0, retrieved 7 April 2013

- ↑ McCarthy, Caroline. "Things to make you happy: Google employs goats". CNET. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Gordon, Ian. "A systems approach to livestock/resource interactions in tropical pasture systems" (PDF). The James Hutton Institute. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Littman, Margaret. "Getting your goat: Eco-friendly mowers". Chicago Tribune News. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Stevens, Alexis. "Kudzu-eating sheep take a bite out of weeds". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Klynstra, Elizabeth. "Hungry sheep invade Candler Park". CBS Atlanta. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Tipping, Don (4 January 2013). "Creating Permaculture Keyline Water Systems" (video). UK: Beaver State Permaculture.

- 1 2 3 Masanobu, Fukuoka (1987) [1985], The Natural Way of Farming – The Theory and Practice of Green Philosophy (rev ed.), Tokyo: Japan Publications, p. 204

- ↑ Fukuoka 1978, pp. 13, 15–18, 46, 58–60.

- 1 2 Fukuoka 1978.

- ↑ "Masanobu Fukuoka", Public Service (biography), PH: The Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation, 1988.

- ↑ Grayson, Russ (2011). "The Permaculture Papers 5: time of change and challenge — 2000-2004". Pacific edge. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ↑ United States Patent and Trademark Office (2011). "Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS)". US Department of Commerce. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Result". IP Australia. 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ↑ Nick Romanowski (2007). Sustainable Freshwater Aquaculture: The Complete Guide from Backyard to Investor. UNSW Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-86840-835-4.

- ↑ Williams, Greg (2001). "Gaia's Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture". Whole Earth.

Bibliography

- Bell, Graham (2004) [1992, Thorsons, ISBN 0-7225-2568-0], The Permaculture Way (2nd ed.), UK: Permanent Publications, ISBN 1-85623-028-7.

- ——— (2004), The Permaculture Garden, UK: Permanent, ISBN 1-85623-027-9.

- Burnett, G (2001), Permaculture: a Beginner's Guide, UK: Spiralseed, ISBN 978-0-95534921-8.

- Fern, Ken (1997), Plants For A Future, UK: Permanent, ISBN 1-85623-011-2.

- Fukuoka, Masanobu (1978), The One–Straw Revolution, Holistic Agriculture Library, US: Rodale Books.

- Hart, Robert (1996), Forest Gardening, UK: Green Books, p. 41, ISBN 978-1-60358050-2; ISBN 1-900322-02-1.

- Hemenway, Toby (2009) [2001, ISBN 1-890132-52-7], Gaia's Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture, US: Chelsea Green, ISBN 978-1-60358-029-8

- Holmgren, David, Melliodora (Hepburn Permaculture Gardens): A Case Study in Cool Climate Permaculture 1985–2005, AU: Holmgren Design Services.

- ———, Collected Writings & Presentations 1978–2006, AU: Holmgren Design Services.

- ——— (2009), Future Scenarios, White River Junction: Chelsea Green.

- ———, Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability, AU: Holmgren Design Services.

- ———, Update 49: Retrofitting the suburbs for sustainability, AU: CSIRO Sustainability Network.

- Jacke, Dave with Eric Toensmeier. Edible Forest Gardens. Volume I: Ecological Vision and Theory for Temperate-Climate Permaculture, Volume II: Ecological Design and Practice for Temperate-Climate Permaculture. Edible Forest Gardens (US) 2005

- King, Franklin Hiram (1911), Farmers of Forty Centuries: Or Permanent Agriculture in China, Korea and Japan.

- Law, Ben (2005), The Woodland House, UK: Permanent, ISBN 1-85623-031-7.

- ———, The Woodland Way, UK: Permanent Publications, ISBN 1-85623-009-0.

- Loofs, Mona. Permaculture, Ecology and Agriculture: An investigation into Permaculture theory and practice using two case studies in northern New South Wales Honours thesis, Human Ecology Program, Department of Geography, Australian National University 1993

- Macnamara, Looby. People and Permaculture: caring and designing for ourselves, each other and the planet. [Permanent Publications] (UK) (2012) ISBN 1-85623-087-2.

- Mollison, Bill (1979), Permaculture Two, Australia: Tagari Press, ISBN 0-908228-00-7.

- ——— (1988), Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual, AU: Tagari Press, ISBN 0-908228-01-5.

- ———; Holmgren, David (1978), Permaculture One, AU: Transworld Publishers, ISBN 0-552-98060-9.

- Odum, H.T., Jorgensen, S.E. and Brown, M.T. 'Energy hierarchy and transformity in the universe', in Ecological Modelling, 178, pp. 17–28 (2004).

- Paull, J. "Permanent Agriculture: Precursor to Organic Farming", Journal of Bio-Dynamics Tasmania, no.83, pp. 19–21, 2006. Organic eprints.

- Rosemary, Morrow, Earth User's Guide to Permaculture, ISBN 0-86417-514-0.

- Shepard, Mark: Restoration Agriculture – Redesigning Agriculture in Nature’s Image, Acres US, 2013, ISBN 1-60173035-7

- Whitefield, Patrick (1993), Permaculture In A Nutshell, UK: Permanent, ISBN 1-85623-003-1.

- ——— (2004), The Earth Care Manual, UK: Permanent Publications, ISBN 1-85623-021-X.

- Woodrow, Linda. The Permaculture Home Garden. Penguin Books (Australia).

- Yeomans, P.A. Water for Every Farm: A practical irrigation plan for every Australian property, KG Murray, Sydney, NSW, Australia (1973).

- The Same Planet a different World (free ebook), FR.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Permaculture. |

- Ferguson, Rafter Sass; Lovell, Sarah Taylor (2013), "Permaculture for agroecology: design, movement, practice, and worldview", Agronomy for Sustainable Development (review), Springer, 34 (2): 251, doi:10.1007/s13593-013-0181-6 – The first systematic review of the permaculture literature, from the perspective of agroecology.

- The Permaculture Research Institute – Permaculture Forums, Courses, Information, News and Worldwide Reports.

- The Worldwide Permaculture Network – Database of permaculture people and projects worldwide.

- The Permaculture Association, UK.

- The 15 pamphlets based on the 1981 Permaculture Design Course given by Bill Mollison (co-founder of permaculture) all in 1 PDF file.

- David Holmgren's web site (co-founder of permaculture)

- Ethics and principles of permaculture (Holmgren’s)

- Permaculture a Beginners Guide – a 'pictorial walkthrough'

- Permaculture – Sustainability and sustainable development

- Urban Permaculture Design – a city lot with over a hundred perennial edible varieties. Permaculture land acquisition discussion.

- A quarter acre suburban property in Eugene, Oregon – grass to garden, reclaim automobile space, elevated/edible landscape, rain water catchment, passive solar design, education

- The Permaculture Activist is a co-evolving quarterly produced by a dedicated handful of entirely part-time folks

- Permaculture Commons is a collection of permaculture material under free licenses